Books

Britain's Royal Families (1989)

"A useful and speedy reference book for royal enthusiasts." (Publishing News)

"This staggeringly useful book ...combines solid information with tantalising appetisers. All the monarchs and their offspring are here in one volume. An indispensable reference book if ever I saw one." (The Sunday Times)

"Interesting reading in a fact-filled book. More than 22 years of research went into its making... It is a must for anyone interested in royalty." (Yorkshire Gazette and Herald)

"An exhaustive guide to the heritage of today`s royal family, and an invaluable source book for royalty watchers, students and researchers."

(Evening Leader, Wrexham)

"This book is a treat." (The Universe)

"The riveting lowdown on all the royal houses of England, Scotland and Great Britain from 800 A.D.." (Manchester Evening News)

"Handy [and] useful. This is a work of reference that is stuffed with unadorned information. The casual dipper may be surprised by what it reveals..." (The Sunday Times, Vulture Classic Choice)

"It may be an exhaustive guide, but it is not an exhausting read." (North West Evening Mail)

"A gem of a book - also great for finding an unusual name for your child and for settling arguments!" (The Bookfiend's Kingdom)

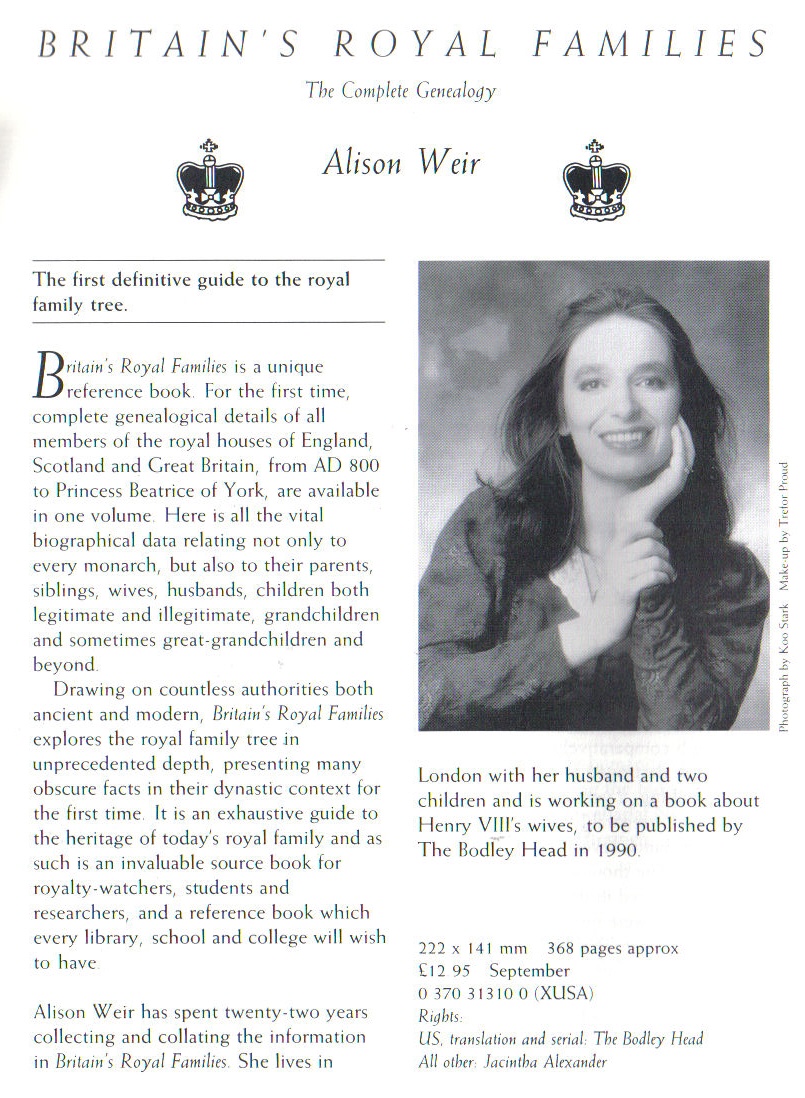

The only two surviving images from my first author jacket photo shoot; taken by Koo Stark at the Lichfield Studios, 1989.

ABOUT BRITAIN'S ROYAL FAMILIES

Me in 1969, 1975 and 1988, the year this, my first book, was commissioned.

Since the age of fourteen I have been fascinated by the British Monarchy. It all began on the day I borrowed my first adult novel from the library, a book entitled Henry's Golden Queen, about Katherine of Aragon. Never before had I devoured a book so avidly, and when I had read to the end I wanted to know: was this this what really happened? After reading two more Tudor novels by Jean Plaidy, I was well and truly hooked, and ready to turn to proper history books to find out the truth.

Within months I had collated sufficient material to produce A Study in Splendour, three volumes of extracts from contemporary sources of the sixteenth century. While compiling this I discovered that my real interest was in the personalities of the age, particularly royal personages. I wanted to find out more about them, and haunted libraries and bookshops in my quest for information. There was no internet then, and books were not always readily available; many of those I wanted were long out of print.

In the meantime I was collecting useful royal biographical and genealogical information and collating it into some form of order. When I was fifteen I wrote a biography of Anne Boleyn based on original sources. My interest was now broadening to encompass earlier and later periods. I now knew what I was going to do. I would compile the genealogical facts I had collated into a biographical dictionary, which I titled The Dictionary of Royal Biography. It was my intention to make it a complete genealogical record of Britain's royal houses from 802 A.D..

By the time I was twenty I had broadly expanded my knowledge of royal genealogy, and learned to be more objective, which was perhaps the most valuable lesson of them all.

I will not bore readers with too many details of the countless hours I spent in libraries over the twenty-two years I spent researching my dictionary. I'm sure there were people who looked askance at the madwoman who sat at her desk getting very excited at the discovery of some crucial fact - and certainly there was one man who did get over-excited beneath the desk next to me. I resolutely ignored him and went on working - and after a couple of hours, no less, he gave up and left!

Between 1965 and 1988 I prepared eight successive versions of my dictionary, incorporating new research every time. It was a mammoth project. By 1986 there were 1,300 entries, all listed in alphabetical order, and including every known member of the royal house of England, Scotland and Great Britain from 802. It would be a hard task explaining to anyone not addicted to genealogy what its attraction is. You could say it is a sophisticated form of collecting (and yes, I have that bug too), or that it affords all the exciting elements of detective work. Researching the genealogy of the British royal family is like piecing together an enormous jigsaw puzzle that fits together in a particularly satisfying way. My early charts were drawn up on rolls of wallpaper. Genealogy is about people at crisis points in their lives - births, marriages, infidelities, deaths. These things engross us all, and when it comes to the monarchy, we are dealing with human beings in a unique situation, whose milestones are ritualised beyond what is normal for the rest of us, and who live in the public gaze. Royal marriages were customarily arranged, and private affairs were frequent. Kings and queens are touched with the aura of sanctity which has always invested our monarchy. All these aspects generate their own special fascination.

Personally, it is the obscure facts, the shadowy people about whom little is known, the infants who died young, the bastards only hinted at, that particularly intrigue me. It is piecing together fragments of less-well-known information with the more famous facts that made researching this work far more than just an academic exercise. For me the project has been a labour of love, a treasured hobby abnd a life-long passion.

For more than twenty years the dictionary was intended as a personal resource for me only. I used it as a basis for other projects, for it was the reference work I had originally sought but never found. In 1987 it occurred to me that others might find it of use. In dictionary form, however, the work was unwieldy, and so I began rearranging it into its present chronological sequence. Thus was born Britain's Royal Families, commissioned by the Bodley Head in 1988.

Early in 1989, when the text was returned to me for indexing, there were still many gaps I had been unable to fill. But by the happiest coincidence, that very week the genealogist Anne Taute very generously gave me a set of H.M. Lane's mammoth genealogical work, The Royal Daughters of England (1911), and in this I found much of the information I needed to fill those frustrating gaps, just before the book went to press.

Britain's Royal Families will never be finished. Information that should be included emerges from time to time. New research is always being done, theories are revised. The royal family is constantly changing. I would like to think that the book is the definitive one on the subject, but I hope at some stage soon to revise it yet again. I just hope that it doesn't take me another twenty-two years to do it!

At Knole, 1972; in my Tudor-style wedding dress, 1972; Ham House, 1973

ORIGINAL PREFACE

"In 1965, when I was fourteen, I read for the first time an adult historical ncvel. It was about Katherine of Aragon, and was entirely forgettable, except for the fact that it left me with a thirst to find out more about the subject. Subsequently, I read many mere novels, and as many history books, and my interest expanded from the early Tudor period to encompass the whole sweep of British, indeed European, history. But right from the beginning, my chief fascination was with the monarchy, and it became my quest, from the time of reading that first novel, to find out as much as I could about Britain's kings and queens.

It was not long before I realised, even in my relative innocence, that a book of biographies incorporating every known fact about our monarchs was going to be out of the question - there was too much material; so, in 1966, I concentrated my efforts on collating a complete genealogical record of all the members of the British royal houses. For two or three years I was at a distinct disadvantage, as I imagined that every detail would have been recorded by someone, somewhere: I only had to look to find the data I needed. Of course, history is not at all like that, as I found out after some formal training in historical objectivity, and after I had become more familiar with the sources for my subject. By 1971 I had accepted the fact that my researches would never be as complete as I wished, and contented myself with recording all that was known or surmised, and with double-checking facts as far as possible. By this time my book, which was then titled "The Dictionary of British Royal Biography", and which had its subjects listed in alphabetical order, had already been re-written five times to incorporate batches of new research. I then took three years off to write a book on Henry VIII's wives, before going back to the "Dictionary".

In 1975/6 I was living in Norwich, where there is an excellent reference library, full of original source material. The staff there were very kind, and obtained for me many rare and ancient books. It was then that my book began to be very substantial, although there was still a good deal to do before I could consider my researches were at an end. I now had entries for all members of the English and Scottish royal houses from 50 A.D. as well as for all the native Princes of Wales and their families. I later dropped the latter as not being in direct line of succession, and it was because I wanted to concentrate on the monarchy that the rulers of the seven English kingdoms that existed before 800 A.D. were also left out of the final book.

My researches continued for a further ten years, boosted by the great surge of interest in the monarchy fostered by the l98l Royal Wedding. The "Dictionary" was re-written, still in alphabetical sequence, in 1985, and again in its final, more manageable format, in 1987, as "Britain's Royal Families". I had set out in 1965 to make a comprehensive genealogical record of the British monarchy, and it had taken me 22 years to do it."

Interview for The Camden New Journal, 19th October 1989

It took Alison Weir twenty-two years of detective work, rooting out and piecing together long forgotten snippets of royal myth and gossip, to write her first book. From the Saxon Kings Egbert and Ethelwulf, right through to the latest blue-blooded babe, Beatrice, Ms Weir has produced a unique catalogue of royal genealogy, tracing who married who, and when their bastard son was killed in which battle. Now with a published book under her belt - after five previous rejections - Alison Weir, mother of two, has settled into her flat perched above Euston fire station to become a full time writer. She leaves behind her a managerial job with the D.H.S.S., and more recently one in the secretariat team of the Thatcher Cabinet.

"I was writing the in-house Whitehall journal, which meant working with the secretaries of all the main Cabinet members," she said. "But I can't talk about that job because of the Official Secrets Act. But one subject which she is rarely short for words on is her obsession with history of the monarchy, which has been channelled into hours of laborious textbook study at the British Library.

"These people have been a constant fascination to me since I was fourteen, which is when I started researching the book," Alison Weir said.

"I've always found it frustrating that there was not a single book which traced the family tree from start to finish, so I decided to turn my hobby into a labour of love and do it myself."

Alison Weir says it is the shadowy past of infant kings and beheaded wives which really fascinates her, and cites the marriage of Richard II to a seven- year-old French girl as a fine example of the dirt to be dug from within the 350 pages.

"He married so he could get hold of some French land, was horribly murdered two years Jater and left the poor girl a widow at the age of nine" Ms Weir laughs. But the current crop of royals also lie close to her heart, and she pins her hopes for the future of the British monarchy on Prince Charles - "a brilliant renaissance man".

"I believe passionately in the Royal Family as an institution, but the mystique is fading and they are becoming a bit like a long-running soap opera. Like myself, there are thousands of casual royal watchers who I hope will love the book. But if they want to read about Diana's clothes or hair-do, it's obviously not for them." JOHN WILSON

Interview for the Brighton Evening Argus, 7 October 1989

From Surrey Life magazine, February 2012:

It's a right royal theatrical month for our county town with the world premiere of 'The King's Speech' play and Guildford Shakespeare Company's 'Richard III' both treading the boards in Guildford. Here the Carshalton-based, best-selling historical author ALISON WEIR, who will be giving a talk to coincide with the latter, joins us to share just a few of her favourite kingly and queenly tales from our county's past...

(Interview by Matthew Williams)

Richard III

Although not especially Surrey connected, the talk on Richard III for Guildford Shakespeare Company means I'll be revisiting a subject I last covered in my book The Princes in the Tower in 1992. He is a king on whom opinions are polarised, and of whom many have an emotional view. My latest book, a novel called A Dangerous Inheritance, returns to the subject and comes out in the spring, so I'm looking forward to seeing GSC perform one of my favourite Shakespeare plays.

Henry VIII

Where to start with Henry VIII? If his palaces had all been preserved then Surrey would look a very different place - from Oatlands to Nonsuch to what's left of Woking. In fact, the area's hunting appealed to him so much that he established the vast honour of Hampton Court for that very purpose. He also founded royal studs to breed horses for hunting and racing, and laid out a racecourse at Cobham, which is thought to have been the first in England. He even destroyed a whole village, Cuddington, to create his grand Nonsuch Palace. You can't imagine the royals getting away with that these days!

Anne Boleyn

She was the starting point for my interest in history when I was a teenager; hers is a story that has always fascinated me. Anne's ascent from private gentlewoman to queen was astonishing, but equally remarkable was her shockingly swift downfall. When Cardinal Wolsey fell from grace, Henry VIII took on Hampton Court Palace and began to embellish it for Anne, but the Great Hall built for her was only finished after her execution. Henry married Jane Seymour ten days after Anne's death; things happened so fast that they forgot to remove Anne's initials from the Great Hall and Anne Boleyn's Gateway, where they can still be seen.

Elizabeth I

It was at Richmond Palace that the Tudor dynasty came to an end, with the death of Elizabeth I. It was one of many palaces at which she (and other kings and queens of the era) would stay, and her favourite because it was warm in winter; thus she would lodge there often, and passed away there in 1603 - although not in the gatehouse (above), as tradition claims.

Prince Leopold and Princess Charlotte

After a honeymoon at Oatlands in Weybridge, which was the country seat of Frederick, Duke of York (second son of George III), Prince Leopold and Princess Charlotte took up residence at Claremont House near Esher. They lived happily at Claremont House until tragically Charlotte died

there in childbirth. An interesting historical side note is that, if Charlotte and her son had lived, Queen Victoria would never have come to the throne.

King George VI

As well as Guildford Shakespeare Company's 'Richard III', Guildford also hosts the first performance of the new play, 'The King's Speech', this month - which is fitting because King George VI had ties with Surrey: he and the late Queen Mother honeymooned at the National Trust's Polesden Lacey in Great Bookham, near Dorking, in May 1923, and there are touching pictures of them walking in the grounds.

Elizabeth II

I think the world has a great affection towards our current Queen because she has always been conscientious and dedicated. I don't think it's any surprise that, despite talk of empire being a thing of the past, she is still greeted with great warmth wherever she goes. I therefore look forward to this year's Diamond Jubilee celebrations.

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge

I'm part of a group of historians called 'The History Girls', and to coincide with Prince William's marriage to Kate Middleton, we published a book, The Ring and the Crown: A History of Royal Weddings 1066-2011. The other authors are Kate Williams, Sarah Gristwood and Tracy Borman, and my section focuses on the medieval, Tudor and Stuart periods. I think William and Kate make a good partnership - and the wedding itself was probably the biggest event of last year. It would seem that the future of the royals is in safe hands.

Alison Weir & Guildford Shakespeare Company

This month, Guildford Shakespeare Company brings the bard's tale of terror and deceit, 'Richard III', to Holy Trinity Church on Guildford High Street, from Friday, February 10 to Saturday, February 25. As part of the run, on Saturday February 18 at 1 pm, Alison Weir will be giving a pre-matinee talk entitled 'Richard III: The Man & The Myth'. (www.guildford-shakespeare-company.co.uk)

ON THIS PAGE I HAVE ADDED MY ARTICLES ABOUT ROYAL SUBJECTS NOT COVERED IN MY PUBLISHED BOOKS.

Proposal for a book commissioned in 1999, but never published, due to competing titles.

THE PRIVATE LIFE OF CHARLES II

Many English monarchs have led promiscuous private lives, but none more so than Charles II, who - not for nothing - was nicknamed Old Rowley after a prolific stallion in the royal stud. Charles, the product of loving, faithful wedlock, found women irresistible, and there is no doubt that many of them felt the same way about him. Numerous sources from the period attest to his charm, his sexual attraction and his innate humanity. He was a man of immense wit and humour, and unusually tolerant for his time.

There have been many books about Charles II, as well as biographies of his many mistresses, but none for many years about his private life. His long-suffering wife, Catherine of Braganza, has been almost entirely overlooked. It is perhaps time to recount the colourful love life of the 'Merry Monarch', and to cast some insights upon his own-character and the characters and motives of the women he bedded.

Charles was born in 1630, the eldest of the nine children of Charles I and Henrietta Maria of France. Until death parted them, he was extremely close to his youngest sister, Henrietta Anne, known as Minette, a relationship that may have influenced many of his attitudes to the opposite sex. From 1642 to 1649, Charles' youth was overshadowed by the Civil War, and Oliver Cromwell, in which the young Prince played his part. His first recorded sexual encounter took place in 1646 in Jersey, and resulted in the birth of a son who became a Jesuit priest.

'Minette'

In 1649, Charles I was beheaded and the monarchy abolished. The titular Charles II was then an exile, dependent on the goodwill of the rulers of France and Holland. During these years abroad, he formed an attachment to Lucy Walter; their son James was later to achieve notoriety as the Duke of Monmouth, claiming that his parents actually had been married and leading a rebellion in support of his claim to the throne.

Lucy Walter

In 1660, the monarchy was restored, and Charles II returned to England to great acclamation. Despite a severe lack of funds and the necessity to tread carefully in the,political sphere, he proceeded to establish one of the most glittering and licentious courts in English history. By now, the King was deeply involved with the beautiful but rapacious Barbara Villiers, whose complaisant husband Roger Palmer was created Earl of Castlemaine as a reward for his discretion. Barbara was a promiscuous virago whose temper was as volatile as her passion. During the period of her ascendancy, she bore six children, although not all were the King's. Charles was in thrall to her charms until he found her in bed with the young John Churchill, future Duke of Marlborough. Discarded, yet in possession of Nonsuch Palace, which she demolished, and the dukedom of Cleveland, Barbara grew fatter as her charms faded, and in desperation took to her bed men of increasingly lowly degree, even, it was whispered, a circus acrobat.

Barbara Villiers

Lady Castlemaine's reign had barely begun, however, when in 1662 King Charles married a Portuguese princess, Catherine of Braganza. Doe-eyed and of sweet disposition, Catherine had been strictly reared and, at 24, had little experience of men. Charles was kind to her, and she fell headlong in love with him. It was not long, however, before the honeymoon came to an abrupt end with her discovery that the King expected her to take Lady Castlemaine as one of her Ladies of the Bedchamber. Catherine, who had thought the affair finished, refused to comply, and when Charles insisted, stubbornly went on refusing, much to the amusement of the whole court. Inevitably, she had to capitulate, and it was not long before she was in the position of having to make friendly overtures to her husband's mistress. The rivalry, betwen them, however, would persist for a decade. During this time, Catherine miscarried several times. The King suffered with her, but never held their childlessness against her, and was unfailing in his kindness and courtesy towards her. Later, when her enemies urged him to divorce her, he would not hear of it. Despite his affection, however, Catherine had to learn to bear his constant infidelities.

Catherine of Braganza

While Castlemaine lorded it over the court, the Queen took into her household a young girl of exquisite beauty and childlike nature called Frances Stewart. The King was captivated by her, and chose her as the model for Britannia on the coinage - an image still retained today. He also laid siege to her virtue, a siege that was successfully withstood, at least until after Frances had married the Duke of -Richmond and Lennox and suffered an attack of smallpox, which wreaked havoc upon her looks.

Frances Stewart

In 1670, after Castlemaine's fall, King Charles received a visit from his beloved sister, Minette, who was unhappily married to the bisexual Duke of Orleans, brother of Louis XIV; she was to die -possibly of poison - soon after this meeting, to Charles' great grief. In her train was a pretty young woman, Louise de Querouaille, whom Louis, knowing his brother monarch's susceptibilities, had sent as a spy, hoping to arrange a secret entente with Charles. Predictably, the King fell for Louise, whose innocent manner concealed a rapacity as great as Barbara Castlemaine's. The affair between the King and this French Catholic spy continued for several years, during which she bore him a son, and was created Duchess of Portsmouth.

Louise de Querouaille

Louise was hated and distrusted by the people of England, but the King's affair with her rival, the pert actress Nell Gwynn, was the stuff of popular legend. Charles's love of the theatre led him to consort with actresses - Moll Davies was another (she bore him a daughter, Mary Tudor, Countess of Derwentwater) - and Nell revelled in the attention, taking every opportunity to denigrate her rival. Once, when her coach was mobbed by angry .Londoners, who thought it carried the hated Louise, she put her head out of the window and yelled, to the delight of the crowd, 'Good people, I am the Protestant whore!' When Louise appreared at court in affected mourning for a foreign prince, Nell arrived in theatrical black weeds, saying she wore them in honour of the Cham of Tartary.

Nell Gwynn

Nell bore the King two sons. In all, Charles II acknowledged fourteen bastards, many of whom he raised to the peerage, and from whom most of the modern nobility can trace their descent. Some of these children were the results of casual affairs, born to women who had only briefly been admitted to the royal bedchamber through the good offices of Chiffinch, the King's Page of the Backstairs.

As the King grew older, he became weary with state affairs and less sexually active. In 1685, on the Sunday before he suffered his fatal stroke, the diarist John Evelyn saw him sitting toying with three of his former mistresses, Barbara Villiers, Louise de Querouaille and Hortense Mazarin-Mancini, a French adventuress whom he had bedded some years earlier. As Charles lay dying, his thoughts centred upon his wife, whose forgiveness he craved, and upon Nell Gwynn. 'Let not poor Nelly starve,' were among his last recorded utterances.

This is a vivid story, rich in detail and anecdote, and it is set in a period illumined by a wealth of source material, not least the diaries of the admiring Samuel Pepys and the disapproving John Evelyn. It would make for a book crammed with human interest, colourful characters, scandal, sex, intrigue and tragedy, all set against a backdrop of the licentious Caroline court, at which it was possible for a woman to give birth to a baby in the midst of a court ball - the infant was found lying on the floor when the dancers dispersed - and still remain anonymous. Above all, there is the charismatic figure of the King, with his all-too-human virtues and failings, and his insatiable drive for sexual intrigue.

AUGUSTA OF WALES

Princess Augusta Frederica of Wales was the first-born child of Frederick, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of King George II and Queen Caroline of Ansbach; her mother was a German princess, Augusta of Saxe-Gotha. Like most of the Hanoverians, Frederick did not get on with his father. Actually he hated his parents. In June 1737 he informed them parents that his wife was pregnant, and due to give birth in October. In fact her due date was earlier, and in July the Prince, discovering that Princess Augusta had gone into labour, smuggled her out of Hampton Court Palace in the middle of the night, to ensure that the King and Queen could not be present at the birth.

George and Caroline were horrified. Traditionally, royal births were witnessed by members of the family and senior courtiers to guard against supposititious children, and Augusta had been forced by her husband to ride in a rattling carriage while labouring and in pain. Queen Caroline raced over to St James's Palace, where Frederick had taken Augusta, and was relieved to discover that the Princess had given birth to a healthy child. But it was, as the Queen described, a "poor, ugly little she-mouse" rather than a "large, fat, healthy boy", which made a supposititious child unlikely, since the baby was so pitiful. The circumstances of the birth deepened the estrangement between Frederick and his parents.

The baby Augusta was born second in the line of succession. Fifty days after her birth, she was christened at St. James's Palace by the Archbishop of Canterbury. Her godparents were her grandfather the King, who was represented by his Lord Chamberlain,and her grandmothers, Queen Caroline and the Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Gotha, who were also represented by proxies).

Augusta's third birthday was celebrated by the first public performance of 'Rule, Britannia!' at Cliveden in Buckinghamshire. She was given a careful education and the negotiations for her marriage began in 1761.

On 16 January 1764 Augusta married Charles William Ferdinand, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel, at the Chapel Royal of St James's Palace. This was purely an arranged political marriage, and Augusta and Charles were always to regard each other with mutual indifference. However, they had seven children.

That year the writer James Boswell visited the court of Brunswick and described Augusta as "excessively affable, talking to me with the greatest ease". He had the honour of dancing a minuet with her, and dined at her court. A modern historian has called her "a stupid, gossiping woman". Augusta regarded Braunschweig, the royal residence in Brunswick, as insufficiently grand. She returned to Great Britain in 1764 with her husband to give birth to her first child, and delayed her return home for a long time after the birth. Her brother, George III, was then King. During their visit to England the Brunswicks were cheered by the crowds whenever they showed themselves in public, to the irritation of the King. During their visit, Augusta's sister-in-law, Queen Charlotte, banned salutes to their honour, which attracted negative publicity towards the Brunswicks. Years later, Augusta expressed the view that Queen Charlotte disliked both her and her mother because of jealousy.

Back in Brunswick, a new palace more to her taste was built for Augusta in Zuckerberg, and called Schloss Richmond to remind her of England. When the palace was finished in 1768, Augusta moved there permanently. She was indifferent to Charles's affairs with Maria Antonia Branconi and Louise Hertefeld, which carried on for thirty years. Her indifference was sometimes seen as arrogance, and it gave rise to rumours and slander. Augusta's popularity was severely damaged by the fact that her eldest sons were born with handicaps.

In 1772 Augusta visited England on the invitation of her mother. On this occasion, she was involved in another conflict with her sister-in-law, Queen Charlotte. She was not allowed to stay at either of the vacant royal residences of Carlton House or St James's Palace, but was forced to live in a small house at Pall Mall. The Queen argued with her about points of etiquette, and refused to let her see her brother the King alone - out of jealousy, it was said.

Augusta had rarely appeared at the court of Braunschweig because of the dominance of her mother-in-law. But when Charles became regent of Brunswick for his father in 1773, her mother-in-law left the court, and Augusta filled the position of first lady in the court ceremonies of Brunswick, although she often took short holidays to her own palace, Schloss Richmond. In 1780 Charles succeeded his father as sovereign Duke of Brunswick, and Augusta became the Duchess consort. In 1795 Augusta's daughter Caroline married George, Prince of Wales, the eldest son of George III.

The Swedish Princess Hedwig Elizabeth Charlotte described the Brunswicks when she visited them in 1799: "The Duke has won many victories as a notable military man, and is witty, literal and a pleasant acquaintance, but ceremonial beyond description. He is said to be quite strict, but a good father of the nation who attends to the needs of his people. After he left us, I visited the Duchess, sister to the King of England and a typical English woman. She looked very simple, like a vicar's wife, has I am sure many admirable qualities and is very respectable, but completely lacks manners. She asks the strangest questions without considering how difficult and unpleasant they can be. The Duchess followed me to Richmond, her country villa a bit outside of the town. It was small and pretty with a beautiful little park, all after an English pattern. As she had the residence constructed herself, it amuses her to show it to others.

"The sons of the Ducal couple are somewhat peculiar. The hereditary Prince is chubby and fat, almost blind, strange and odd - if not to say an imbecile - attempts to imitate his father but only makes himself artificial and unpleasant. He talks continually, does not know what he says and is in all aspects unbearable. He is accommodating but a poor thing, loves his consort to the point of worship and is completely governed by her. The other son, Prince Georg, is the most ridiculous person imaginable, and so silly that he can never be left alone but is always accompanied by a courtier. The third son is also described as an original. I never saw him, as he served with his regiment. The fourth is the only normal one, but also torments his parents by his immoral behaviour."

In 1806, when Prussia declared war on France, the Duke of Brunswick, now 71, was appointed commander-in-chief of the Prussian army. In October that year, at the Battle of Jena, Napoleon defeated the Prussian army, and, on the same day, at the battle of Auerstadt, the Duke of Brunswick was seriously wounded. The Duchess Augusta, with two of her sons, and a widowed daughter-in-law, fled her ruined palace for Altona, where she was present with her daughter-in-law, Marie of Baden, at her dying husband's side.

As the French army was advancing, Augusta was advised by the British ambassador to flee with Marie, and she had to leave left shortly before her husband's death. The two ladies were invited to Sweden by Marie's brother-in-law, King Gustav Adolf. Marie accepted and left for Sweden, but Augusta went to Augustenborg, a small town east of Jutland. Here she remained here until her brother, George III, finally gave in to her please and in September 1807 allowed her to come to London.

She moved into Montague House, Blackheath, with her daughter, Caroline, Princess of Wales, but soon fell out with her and purchased the house next door, which she renamed Brunswick House. Here she lived out her days, dying in 1813 from a flu-like illness, aged 75. She was buried in the royal vault of St. George's Chapel at Windsor Castle. "The poor little she-mouse" had turned out as unremarkable as her grandmother had feared, and it is unlikely she would have made a memorable queen.

THE PRINCESS`S SECRET: A STORY OF KENSINGTON PALACE

by Alison Weir (2010). Written for Historic Royal Palaces, to be given to those making donations for the restoration of Kensington Palace.

On 27 May 1848, in an apartment at Kensington Palace, an old lady of seventy died, as quietly as she had lived - or so it seemed. Her name was Princess Sophia Matilda, and she had been born the twelfth of the fifteen children of King George III and Queen Charlotte.

Thanks to the generosity of her brother, George IV, Sophia - surrounded by knick-knacks and the mementoes of an earlier age - had lived in the palace since 1820, apart from a short period from 1838-43, when the `ruinous condition` of the building obliged her to take a house nearby. Her neighbours in the palace were her younger brother, Augustus, Duke of Sussex, and then, after his death in 1843, his widow, the Duchess of Inverness, whom he had married clandestinely, in contravention of the Royal Marriages Act of 1772; and Sophia`s widowed sister-in-law, Victoire, Duchess of Kent, whose daughter Victoria no longer lived at Kensington Palace, for she had become Queen in 1837.

Sophia had never married. Her father, the moral, devout and uxorious George III, was decidedly averse to any of his six daughters leaving home. Two managed to escape their suffocating spinster existences by marrying German princes: the eldest, Charlotte, Princess Royal, was thirty before she wed the corpulent Duke of Wurttemberg and moved to Stuttgart, while poor Elizabeth had to wait until she was forty-eight to find her prince, the `vulgar-looking` Frederick, Landgrave of Hesse-Homburg, who rarely bathed and stank of garlic and tobacco. A third sister, Mary, married her cousin, William, Duke of Gloucester - known as `Silly Billy` - when she was forty.

The other sisters, Augusta, Sophia and Amelia, were condemned to lives of sterile frustration, and complained that they were living in a `nunnery` under their mother`s strict supervision at Kew, Windsor, and Buckingham House in London. The Queen had diligently ensured that they were all well-educated, and they were now intelligent young women with considerable talents.

Unsurprisingly, they managed to circumvent their mother`s scrutiny and sought an outlet in secret love affairs. Rumour linked Augusta with a page surnamed Ramus, or asserted that she had secretly wed a royal equerry, Major General Sir Brent Spencer. Although the evidence for each assertion is dubious, Augusta and Spencer did enjoy a ten-year romance. Amelia, the King`s favourite, may have entered into an illegal marriage with the Honourable Charles FitzRoy, a descendant of Charles II, but again, proof is lacking. It was Amelia's death from erysipelas in 1810 that finally tipped George III into his final phase of what was then thought to be madness - although, of course, we now know that he had porphyria, from which it has been conjectured that his daughter Sophia also suffered. That would account for the spells of ill health that troubled her through her life.

Sophia, fair and floridly pretty like most of her race, also courted scandal. She bore an illegitimate child.

That infant, Thomas, was born early in August 1800 - he was baptised on the 11th - in Weymouth, when Sophia was twenty-three. His father was another of King George`s equerries, General Thomas Garth, whose family lived near Weymouth, and who was thirty-three years older than Sophia, and no oil painting. A fellow equerry, Robert Fulke Greville - who guessed that Garth had got Sophia pregnant - called him `a hideous old devil, old enough to be her father and with a great claret mark on his face`. Princess Mary referred to this birthmark as `the Purple Light of Love`. The child was acknowledged by General Garth and given his surname.

General Garth had occupied the room above Sophia`s at Windsor. The princesses were so secluded from the world that they were ready to capitulate to the first man who approached them, and to Sophia, this middle-aged gentleman represented all that she was missing in life, and she became so infatuated that `she could not contain herself in his presence`. Determined to have him, she faked `cramps` and `spasms`, got herself moved from her sisters` lodging at Windsor to the one occupied by the King and Queen, and then, when they were away in London, contrived to smuggle Garth into her room.

It is possible that Sophia and General Garth were secretly married soon after her arrival in Weymouth that year - a portrait of Sophia in old age does show her wearing a wedding ring. There is, however, no substance to the tale that the ceremony took place at Puddletown Church in Dorset. Even so, any secret marriage between Sophia and her lover would have been invalid because, under the provisions of the Royal Marriages Act, passed in 1772 in the wake of George III`s shocked reaction to the unsuitable marriages of his brothers, any marriage made by his children without the consent of the sovereign was automatically null and void. So even if she did have a marriage certificate, Sophia`s son was legally a bastard.

Her pregnancy was, of course, concealed from her father and from the public at large, although a number of people at court knew about it. George III was told that his daughter was suffering from a dropsy that had made her stomach swell, and that a `roast beef cure` had proved successful. The King was fond of telling those who knew better that this cure was `a very extraordinary thing`. Maybe, as the father of fifteen children, he did suspect what had happened, yet Sophia was often ill; her mother and sister Charlotte suffered intermittently from dropsy, so her explanation for her indisposition was credible.

There was no question of Sophia bringing up her child herself. The scandal would have been too great. So she returned to her former dull, genteel existence, and visited little Thomas from time to time at the house of Sir Herbert Taylor, the King`s private secretary, at Weymouth, where the boy grew up. In the December following her confinement, she wrote to a friend, Lady Harcourt of her `distressed and unhappy days and hours`. She said she needed `time to recover my spirits, which have met with so severe a blow. It is grievous to think what a little trifle will slur a young woman`s character for ever.` Yet what had befallen her was no mere trifle: she had risked irretrievably ruining her reputation and bringing the monarchy into disrepute at a time when Britain was at war with Napoleon Bonaparte.

In 1811, Sophia wrote to her brother, the Prince Regent, referring to herself and her unmarried sisters as `four old cats`. She continued in humorous vein: `I wonder you do not vote for putting us in a sack and drowning us in the Thames.` The Prince was fond of his sister and often visited her and sent her gifts.

General Garth always behaved with gentlemanly courtesy towards Sophia whenever they met, and never lost favour with the royal family. But Sophia`s son, Thomas Garth, was, according to Greville, `an idiot as well as a scoundrel`. When General Garth fell gravely ill and thought himself at death`s door, he gave his son, for safe-keeping, highly compromising documents attesting to the young man`s true identity. The younger Garth deposited the documents in Snow`s bank, and attempted, through the medium of Sir Herbert Taylor, to blackmail his royal relations, demanding a substantial lump sum and an annual pension of £3,000. But then his father unexpectedly recovered and demanded the return of the papers. Young Garth refused, accused Taylor of failing to put them in the bank, and tried to obtain an injunction against him.

By now, the gutter press had got hold of the story, and a vicious rumour was spread that Sophia`s own brother, the unpopular Ernest, Duke of Cumberland, whose own family even regarded him with horror, had fathered a child on her, and that - at the King`s plea - General Garth had chivalrously stepped in and acknowledged the boy as his own to avoid an epic scandal. Sophia`s only comment on this was that Ernest`s conduct towards her had been kindly but `a little imprudent at times`. Whatever she meant by that, Ernest could not have got her pregnant for he was overseas at the time she conceived. This malicious tale is thought to have been spread either by Princess Lieven, wife of the Russian ambassador and a known scandal-mongerer, or by the unstable Caroline of Brunswick, the rejected wife of the Prince of Wales.

Sophia`s son fled abroad to escape his creditors; he died after 1839, leaving children of his own. General Garth died in 1829, aged eighty-five and - to all outward appearances - a confirmed bachelor.

Poor Princess Sophia never saw her son again. She continued in her barren existence, plagued by chest cramps that may have been psychosomatic, and possibly a cry for love and attention. In the 1830s, after she moved into Kensington Palace, she supported the Duchess of Kent and the latter`s comptroller, Sir John Conroy, in their schemes to seize the regency and retain power once the young Princess Victoria had succeeded to the throne; Sophia acted as their `spy at court`, reporting to Conroy what her brother, William IV, was saying about him and the Duchess. The young Victoria was aware of this plotting, and was said never to have trusted her Aunt Sophia as a result, yet she was unfailingly kind to her after becoming Queen in 1837.

Sophia was now advancing into a dignified old age. In 1838, she woke up blind in one eye. Cataracts were diagnosed, but an operation proved unsuccessful. `Dear Sophy is wonderfully well, and so sweet-tempered and resigned to her affliction of blindness, but it is painful to witness the poor dear,` Princess Augusta recorded after a visit to her sister. Thereafter, Sophia`s chief recreation was short drives in Kensington Gardens and Hyde Park. She refused to have a lady companion because she could not bear to imagine someone sitting opposite her looking bored, but the niece of her former governess came regularly to read to her. In her latter years, she could barely walk, and had to be carried around her apartment in a chair.

Sophia was both blind and deaf when she died in 1848, surrounded by family members, and holding her sister Mary`s hand. She was unconscious for two hours before the end came. `Thank God my poor dear Aunt Sophia did not suffer in her last moments,` her niece recorded. Her last request was to be buried near her late brother, the Duke of Sussex, in fashionable Kensal Green cemetery, where her stone monument, in the form of a sarcophagus, can be seen today. She may be accounted yet another of the tragic princesses of Kensington Palace.

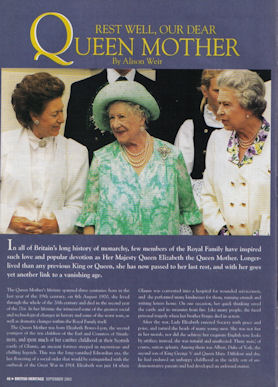

REST WELL, OUR DEAR QUEEN MOTHER by ALISON WEIR

British Heritage, September 2002

The full text of this article follows:

In all Britain's long history of monarchy, few members of the ruling caste have inspired such love and popular devotion as Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother. Longer-lived than any previous king or queen, she has now passed to her last rest, and with her goes yet another link with a vanished age. For the Queen Mother's lifetime spanned three centuries: born in the last year of the 19th century, on 4 August 1900, she lived through the whole of the 20th century, and died in the second year of the 21st. In her lifetime she witnessed some of the greatest social and technological changes in history and some of the worst wars, as well as dramatic changes within the royal family itself.

The Queen Mother was born Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, the second youngest of the ten children of the Earl and Countess of Strathmore, and spent much of her happy and carefree childhood at their Scottish castle of Glamis, an ancient fortress steeped in mysterious and chilling legends. This was the long-vanished Edwardian era, the last flowering of a social order that would be extinguished with the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. Elizabeth was just fourteen, and when Glamis was converted into a hospital for wounded servicemen, she performed many kindnesses for them, running errands and writing letters home. On one occasion, her quick thinking saved the castle from being destroyed by fire and its treasures burned. Like many people, she faced personal tragedy when her brother Fergus was killed in action.

After the war. Lady Elizabeth emerged into Society with grace and poise, and turned the heads of many young men. She was not fast in her morals, nor did she achieve her exquisite English-rose looks by artifice; instead, she was natural and unaffected. There were, of course, suitors aplenty. Among them was Albert, Duke of York, second son of King George V and Queen Mary. Diffident and shy, he had endured an unhappy childhood as the sickly child of undemonstrative parents, and had developed a painful stutter.

At this time, Elizabeth was particularly attracted to another young man, Lord James Stuart, but her mother disapproved of him and made certain that Prince Albert was invited to Glamis instead. Albert's mother, Queen Mary, was also a guest, at a time when Lady Strathmore was ill and Elizabeth was acting as hostess in her place. The Queen was very impressed with her, and certain that she would be the right wife and helpmeet for 'Bertie', as he was known in the family.

Prince Albert proposed twice, but Elizabeth turned him down on the grounds that she had no wish to undertake the public duties that life as a member of the royal family would involve. Yet the couple continued to meet and grow closer, and when he asked her again if she would marry him, the answer was yes. The King and Queen were overjoyed to receive the news in a telegram from their son, which bore the simple message, 'All right. Bertie.' George V was entranced with his future daughter-in-law: a stickler for punctuality, he astonished all present by making excuses for her when she was late for dinner, and even when she gave an ill-advised interview to the press - her first and last - he was indulgent and forgiving.

The young couple were married in 1923 in Westminster Abbey. Elizabeth took as naturally to royal life as if she had been born to it, and won hearts everywhere with her charm, her gracious smile and her common touch. All who met her were left with the impression that she had been genuinely interested in them. As for Bertie, he was entranced: Elizabeth, who was warm and loving, had a gift for creating a happy home, and he had never been so happy in his life.

In 1926, the couple's joy was complete when their first child was born, the future Queen Elizabeth II, who was known in the family as Lilibet. The baby was born by Caesarian section, as was her sister, Princess Margaret Rose,-who arrived in 1930. The Duchess was thrilled with her first child, yet when Lilibet was nine months old, the Duke and Duchess were sent abroad on a world tour that lasted six months. Elizabeth felt the parting dreadfully, even though Queen Mary kept her up-to-date on her daughter's progress, but in those days it was held that duty should come before personal considerations. Everywhere she went, the Duchess was all smiles, and no one would have guessed how much she was missing her baby.

The Yorks, who soon afterwards moved to a fine mansion at 145 Piccadilly, seemed to be the ideal family. During the early 1930s, the public and the media could not get enough of the little Princesses, who were beautifully dressed and impeccably behaved, and enjoyed a happy home life in which their parents were far more involved than most aristocratic mothers and fathers. Then the outside world once again intervened to interrupt this idyll. In 1936, George V died and his eldest son succeeded as Edward VIII. Few knew at that time that the bachelor King had for some time been involved in a relationship with an American divorcee, Mrs Wallis Simpson, a woman of whom the Duchess of York most certainly did not approve. When it became clear that the King intended to marry Mrs Simpson, the press, which had maintained an unusually restrained silence on the affair, erupted in condemnation, as did the Prime Minister and the Archbishop of Canterbury: it was unthinkable that the head of a church that did not recognise divorce should marry a woman who had two husbands still living.

In the end, Edward VIII abdicated in favour of his brother, the Duke of York. The distressed Duke did not want the responsibility of kingship: he was not trained for it and still stuttered badly. Yet he had no choice. It was fortunate that the new King George VI, as he was styled, had as his consort a woman who was determined to make a success of him. Although Elizabeth was as reluctant as he, she made the best of the situation, and settled into the role of Queen-Empress with confidence and grace. She engaged a speech therapist to help her husband, and whenever the King had one of his intermittent outbursts of rage and frustration, she would soothe him and keep him calm. Always she was behind him, kindly and supportive, and the monarchy, which had sunk to a low ebb at the time of the abdication, rapidly recovered its prestige, thanks almost entirely to her efforts.

When, in the late 1930s, the King and Queen paid state visits to France and America, they received an ecstatic welcome and were able to help forge ententes that would stand Britain in good stead in the years to come. For war was looming on the horizon. The rise of Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Germany had led to the occupation of the Sudetenland and Austria, and when Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, Britain declared war. The Princesses were sent to the safety of Windsor Castle, but when it was suggested that the King and Queen take them abroad, the Queen adamantly refused. They would all stay to take their chance with the rest.

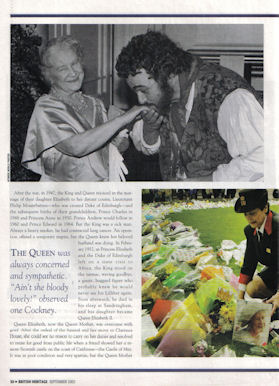

When the Blitz began in 1940, King George and Queen Elizabeth began visiting the bombed-out areas, comforting and cheering the people, the Queen always concerned and sympathetic. 'Ain't she bloody lovely!' one Cockney observed. Buckingham Palace was bombed several times, but the Queen merely commented, 'At last, I can look the East End in the face.' Her letters reveal how affected she was by the suffering of the people.

She was tireless in her war efforts. She addressed the women of Britain on radio, held sewing groups at Buckingham Palace, and visited the wounded in hospital. When told that behind one door there lay a man with horrific burns that might upset her, she insisted upon seeing him, her smile as unflinchingly gracious as ever. She and the King forged warm friendships with Winston Churchill and President Roosevelt, and when the war ended, and the royal family emerged onto the balcony of Buckingham Palace with Mr Churchill, they became a focus for the joy and hopes of the people.

After the war, in 1947, the King and Queen rejoiced in the marriage of their daughter Elizabeth to her distant cousin, Lieutenant Philip Mountbatten, who was created Duke of Edinburgh, and the subsequent births of their grandchildren. Prince Charles in 1948 and Princess Anne in 1950. But the King was a sick man. Always a heavy smoker, he had contracted lung cancer. An operation offered a temporary respite, but the Queen knew her beloved husband was dying. In February 1952, as Princess Elizabeth and her husband left on a state visit to Africa, he stood on the tarmac waving goodbye, a gaunt, haggard figure who probably knew he would never see his Lilibet again. Soon afterwards, he died in his sleep at Sandringham, and his daughter became Queen Elizabeth II. .

Queen Elizabeth, now the Queen Mother, was prostrated with grief. After the ordeal of the funeral and her move to Clarence House, she could see no reason to carry on, and was resolved to retire for good from public life when a friend showed her over remote Scottish castle on the coast of Caithness - the Castle of Mey. It was in poor condition, and very spartan, but the Queen Mother could see its potential and bought it. Over the following months, as she carefully restored it as a holiday home for herself, the healing process began, and she came to realise that she could still be of service to her country. After that, she never looked back, but changed the role of a Queen Mother - traditionally very much a low key one - into something very high-profile. She undertook a wide range of public engagements, went on foreign tours, began once more to enjoy a social life, and established herself as a serious art collector. She also took up horse racing, which was a passion to the end of her life.

Within a very short time, she had regained her former status and become the nation's favourite grandmother. Charming and delightful in her trademark pastel clothes and flowery hats, she won golden opinions everywhere. Her great popularity endured to her death in March 2002, surviving and transcending all the tragic scandals that have embroiled the royal family. To the end, the Queen Mother preserved the traditions of monarchy to which she was reared, the traditions of duty, dignity, service and personal obligation, which may seem out of date today but have certainly served both her and the people of Britain well. We will never see her like again, this grand old Victorian who has guided and inspired the monarchy for well over sixty years. Without her, we shall all be the poorer.

MISCELLANY

My unpublished English Aristocratic Pedigrees is a vast work still in progress, which I have been researching since before 1970, although there is little prospect of it ever being published, simply because I may never get time to finish it and draw up all those family trees to a standard acceptable for publication.

Britain`s Royal Families has been updated twice, for the 1996 and 2002 editions. However, it`s the kind of book that is never finished. I keep a working copy, which is covered in blue ink revisions, but sadly, when Vintage reissued the book in 2008, they didn`t give me the opportunity of updating the text again. I hope to work on a comprehensively updated edition soon.

There was a relatively small print run of the hardback of Britain`s Royal Families, and it is now very rare indeed. It appears from time to time in online bookstores, but at very high prices - up to about £450. Back in the Nineties, I received many letters asking for help with tracking down the hardback, and it got to the stage where the publishers sold their own publicity copy. The book has been revised and reprinted three times in paperback - the latest edition was published by Vintage in 2008. This is the only one of my books never to have been published in America.

I recommend a very good wall chart, Kings and Queens of Great Britain, by Anne Taute. It`s not as exhaustive as Britain's Royal Families, but it is pretty accurate and beautifully produced. You`ll need to do an online search for it, as it came out in 1991 and is out of print, but there are copies out there. Anne Taute very generously gave me her copies of the very rare volumes, The Royal Daughters of England, which enabled me to fill in many gaps before Britain's Royal Families went to press.

CRISIS? WHAT CRISIS?

Letter from Alison Weir to the Evening Standard, 9 June 1992:

"The press refers to the alleged troubles of the Prince and Princess of Wales as "the worst crisis the Royal Family has faced since the abdication". Nonsense. The abdication was a constitutional crisis, this is not. Under the Constitution, the Prince of Wales has no formal role and nor does his wife. There is no evidence that Prince Charles has failed to prepare himself for his future role of King. The historical role of the Princess of Wales is to produce heirs to the throne, to promote British interests and to perform charitable works. Princess Diana has performed these functions well and shows every sign of intending to continue to do so. Where then is a constitutional crisis? The private aflairs of the Prince and Princess of Wales are not, and should not be, a matter for public speculation, as they are of no concern to the public. What matters is that the Prince and Princess of Wales show to the public a united front and carry out their state, ceremonial and dynastic duties. The current trend in the reporting of royal affairs by the press trivialises the monarchy and can only damage it in the long run. Can the press not sell papers by reporting proper news, instead of filling the pages of our newspapers with intrusive, prurient and insensitive trivia which can only cause deep distress to the persons involved and offend everyone with any respect to the privacy of others. - Allson Weir, Euston Square, NW1."

My family trees use symbols that are standard in genealogy. They are:

Crucifix symbol = murdered

Crossed swords = killed in battle

Arrow pointing downwards = issue of marriage

broken line denotes bastardy

b. = born

c. = circa (around)

d. = died

ex. = executed

m. = married

? = uncertain