Books

Children of England: The Heirs of King Henry VIII/The Children of Henry VIII (1996)

"Weir writes in a pacy, vivid style, engaging the heart as well as the mind. This, her fourth book on the Tudors, affirms her pre-eminence in this field." (Amanda Foreman, The Independent)

"This irresistibly engaging book - described without exaggeration in the blurb as `popular history at its best`….Readers will enjoy and profit from an abundance - but never an excess - of fascinating detail." (The Tablet)

"The brilliance of this author is her scrupulous research…she keeps us focused on those real-life children and shows what made them such frightened and frightening figures." (BBC Homes and Antiques)

"Written with painstaking research, it is highly readable and entertaining, with shocking insights into the royals of four centuries ago… Vivid, fascinating, necessary for every bookshelf." (The Richmond and Twickenham Informer, Book of the Month)

"Engrossing narrative history, scrupulously researched, alive with character and incident and scenes showing that the reality of the past usually holds more interest than historical fiction." (The Boston Globe)

"Weir imparts movement and coherence while recreating the suspense her characters endured and the suffering they inflicted." (The New York Times Book Review)

"Alison Weir does full justice to the subject." (Newsday)

"With impressive narrative skill, Alison Weir pilots her readers through the ceaseless tide of intrigue which surged around the four heirs of Henry VIII. Her mastery of detail brings their tempestuous lives into sharp focus…This is full-blooded history." (The Independent)

"A readable and resourceful chronicle…colourful but scrupulous." (New Statesman and Society)

"A welcome variation on an old theme. This is popular history at its best. There is an underpinning of scholarship, however; Weir writes accessibly and brings her characters to life." (The Daily Telegraph)

"Miss Weir makes full use of the available material to give us a thoroughly enjoyable and well written composite biography. In telling her tale, she gives a good insight into Tudor court life, not altogether a pleasant sight." (Contemporary Review)

"These brutal episodes make for a good story, which the author tells with gusto…a shrewd analysis of human nature in a cruel age." (St Louis Post)

"This book is not just well researched, but also well written and up to the standard of her excellent earlier eforts... This book reads like a thriller... This is a thoroughly readable book appealing to the historian, and a great introduction to a fascinating period of our history." (Yorkshire Evening Press)

"Worthy, well-written and incredibly well-researched." (South Wales Evening Post)

"Weir can always be counted on to tell a superb story." (Booklist)

"Fascinating... Alison Weir does full justice to the subject." (Philadelphia Inquirer)

"Weir provides captivating glimpses of the daily experiences that shaped her young subjects' personalities." (Newsday)

"Intelligent, populist and unputdownable." (Venue)

"This is popular history at its best... The author provides a detailed, fascinating and often shocking insight into the royal household of four centuries ago." (Bolton Evening News)

"This fascinating tale of murder, jealousy, religious fanaticism and political scandal makes the modern dysfunctional royal family appear quaint by comparison... Weir's narrative brings to life the tangled relationships and religious tensions that dominated England during the 16th century." (Kirkus Reviews)

"Alison Weir combines those rare qualities - excellent storytelling and historical accuracy. 'Popular history' this may be, but none the worse for that!" (Western Morning News)

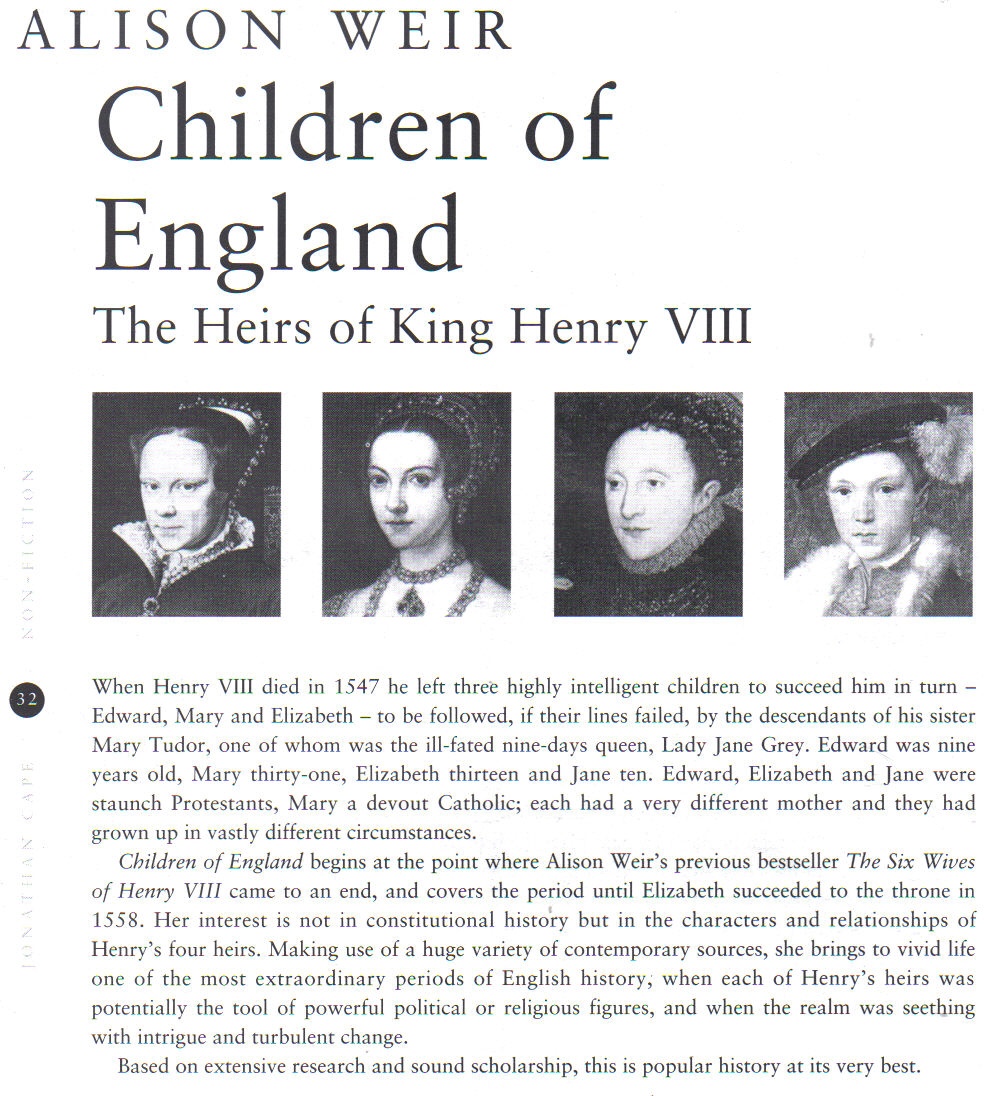

When Henry VIII died in 1547, he left three highly intelligent children of varying ages and temperaments. The King's will decreed that the throne pass in turn to his son Edward, aged nine, his daughters, Mary, aged thirty-one, and Elizabeth, aged thirteen, and then to the heirs of his deceased sister, Mary, Duchess of Suffolk. Although his son succeeded him, the terms of King Henry's will were not honoured by the ambitious John Dudley, Duke if Northumberland, who ruled England as Lord President of the Council at the tine of Edward VI*s tragic early death from tuberculosis in 1553. Dudley had married his own son Guilford to Lady Jane Grey, granddaughter of Henry VIII's sister Mary, seeing that marriage as a means of preserving his own power and the Protestant religion that had been established in England under Edward.

Edward VI's lawful heir was his staunchly Catholic sister Mary, a prim spinster now aged thirty-seven, but Northumberland persuaded the ailing King to set aside the claims of his sisters and sign a device naming Jane Grey as his heir. Jane reigned for nine days before Mary's forces were victorious over Northumberland's, and in July 1353 Mary became queen. The Duke, his son and daughter-in-law all perished on the block.

Mary I's accession heralded the counter-reformation In England, the restoration of Catholicism and the country's return to the Papal fold. This brought in its wake winds of change that fanned the flames of Smithfield and elsewhere, wherein perished nearly three hundred Protestants, among them Archbishop Cranmer, the architect of Henry VIII's Reformation.

Mary's loveless marriage to Philip of Spain was deeply unpopular. Her two phantom pregnancies ended in humiliation, heartbreak and - ultimately hastened the Queen's death in November 1558. Mary was succeeded by her half-sister, the twenty-five-year-old Elizabeth.

This book is not primarily a history of England during the reigns of Edward, Jane and Mary, but an exploration of the characters of three royal siblings, and a chronicle of the relations between them throughout the period 1547 to 1558. Theirs were not easy relationships for several reasons. The three children of Henry VIII all had very dissimilar characters; while they took after their father in many ways, they all inherited

diverse characteristics from their mothers, the first three of Henry's six wives. Each had spent his or her formative years in vastly differing circumstances; each had enjoyed - or suffered - varying relations with their august father. Mary's mother had been supplanted in King Henry's affections by Elizabeth's mother, Anne Boleyn, who had been the bastardised Mary's bitter enemy, and was seen by Mary as responsible for the reformed religion gaining a foothold in England. Nevertheless, the maternally-Inclined Mary, thwarted by circumstances of becoming a mother herself, dearly loved her little stepsister Elizabeth, seventeen years her junior, even though the child had supplanted her in her father's affections and in the line of succession to the throne. And when Elizabeth in turn, at two years old, was also declared a bastard, her mother having been sent to the block for treason, it was Mary who took the child under her wing, and Mary who, over the years, tried to ensure that she was brought up in the Catholic faith. Edward, by contrast, knew nothing but his father's constant love. Had he lived, he would probably have been the least attractive of the Tudors. His early death in 1553 was not only a merciful release from an horrific illness, but a blessing for Mary Tudor.

Mary I was a complex character in whom genuine kindliness warred with the dictates of religious fanaticism. At once courageous and highly emotional, she was so innocent that even in her thirties she did not know what a whore was. Although the prospect of sexual relations was repugnant to her, she conceived an almost romantic love for Philip of Spain even before she had met him. She had already fallen in love with his portrait. The reality of their married life, and two phantom pregnancies, broke her heart.

Mary's sister Elizabeth was a constant thorn in her side. Having resolved to bring about a counter-Rrformation, Mary was concerned that Elizabeth should profess the same love for the Catholic faith as she did herself. Elizabeth was the heiress to the throne until Mary bore a child, and Mary wanted an assurance that her work would be carried on after her death, Elizabeth reluctantly conformed outwardly to what Mary required, but the Queen could never be certain that her heart was in it and that she was not simply attending Mass as a matter of expediency. Nor could Mary be certain that Elizabeth had not plotted to marry Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon, Mary's former suitor and the last of the Plantagenets, and overthrow her. Mary's suspicions and jealousy of her sister led to Elizabeth's imprisonment in the Tower, and might well have led to her execution had any evidence of treason been found. Thereafter, Elizabeth lived a quiet life in the country, coming to court only occasionally and doing her best to stay out of trouble. Nevertheless, as the Queen's unpopularity increased, and the count of martyrs grew ever higher, Elizabeth underlined the difference between them by dressing in the sober dark colours favoured by strict Protestant women, in stark contrast to Mary's gorgeous court gowns, which were adorned and bejewelled like the images of the saints found in Catholic churches.

Mary could never trust Elizabeth, nor could she be sure that King Philip's interest in her sister was strictly political. And when Mary died in November 1558, she did so in the bitter knowledge that, not only had she failed in almost everything she had tried to do, but she had also been deserted by most of her courtiers, who had gone to Hatfield to pay their addresses to her sister.

Elizabeth had trodden a perilous path from the age of two. Although still technically a bastard, she was recognised as the only possible successor to her sister. At the age of twenty-five she became Queen of England, when it might have seemed remarkable that she still had a head on her shoulders. Small wonder that when the news of Mary's death and her accession was brought to her, she knelt reverently beneath an old oak tree in the park at Hatfield and said, "This is the Lord's doing; it is marvellous in our eyes."

This book portrays the very different personalities of the children of Henry VIII, and the personal relationships between them, relationships that affected the course of England's history, and were rarely easy, for they were complicated by personal, political or religious considerations. There is a wealth of documentary evidence contemporary to the period that underpins their stories: numerous personal letters, the great calendars of state and diplomatic papers, memorials by contemporary writers, and the invaluable journal of Edward VI, as well as more mundane records such as privy purse expenses, which often render fascinating information.

This was an age in which the personalities of monarchs and their family relationships had the power to influence government. It is interesting - and indeed vital to our understanding of the period - to investigate what shaped the characters of three of the most interesting monarchs ever to have graced the throne of England, Our human condition makes us eager to learn about the private things: the everyday trivia, the scandals, and the strange familiarity of ages long gone. We want to bridge the gap, to discover that even these long-dead kings and queens felt as we do, and get to know them through the writings and mementoes they have left behind them. It is a tale full of fascinating discoveries, both about them and about the times in which they lived, set against a background of the turbulent and often violent politics of the age, the stark Protestantism and destruction of Edward's reign, which gave way to the burning fanatieisra of Mary's; the intrigues of the court, with here and there a love story; and the crises of the period: Kett*s rebellion, the coup of 1553, Wyatt's rebellion, and the loss of Calais, England's last possession in France.

There is a whole cast of supporting characters, notably the Seymour brothers, uncles to Edward VI: Edward, Duke of Somerset and Lord Protector of England, and Thomas, Lord High Admiral, fourth husband of Katherine Parr, and would-be seducer of the Lady Elizabeth, Both Edward and Thomas Seymour ended their lives on the block, There are the Dudleys - John, Duke of Northumberland, who succeeded Somerset as ruler of England; his son, Guilford, married to Lady Jane Grey, who occupies a poignant niche in this book, along with her unhappy sisters. Another of Northumberland's sons, Robert Dudley, would share Elizabeth's imprisonment in the Tower and perhaps there conceive a life-long love for her. There are the Bishops, Latimer, Ridley and bloody Bonner; Archbishop Cranmer, who Mary sent to the stake, and his successor, Reginald Pole, an intellectual fanatic who was partly responsible for the fires of Smithfield, and who died on the same day as Mary, leaving the way clear for the establishment of the Anglican Church of England.

One of the chief protagonists is Philip of Spain, the cold, bigoted and lecherous prince who married Mary, a lady eleven years his senior. Philip's less than kingly behaviour in the chambers of the ladies of the court, and his callous treatment of his wife are well tilled soil, but his attitude to Elizabeth is more ambiguous.

Lastly there are the "domestic" characters, among them are Barnaby Fitzpatrick, Edward VI 's whipping boy, who had to suffer the punishments meted out to his master; Kat Astley, Elizabeth's devoted governess, who knew more than she wished to reveal about the affair with Seymour; and Susan Clarencieux and Jane Dormer, Mary's ladies and the people closest to her. Dormer's memoires are a major source

for the reign.

The story is set against a backdrop of magnificent Tudor palaces: Hampton Court, Greenwich, Richmond, Nonsuch, St James's, Windsor and Whitehall, as well as against the quiet tranquillity of Hunsdon and Hatfield. Sometimes the scene shifts to the Tower, which by this date was already invested with a sinister reputation. Elizabeth's mother had died there, by the sword, and she herself initially refused to enter it on her arrival as a prisoner in 1554, having a superstitious fear of the place, and with good reason, for it was not so very long since Lady Jane Grey had been beheaded there, aged just seventeen.

Set in a period of turbulent change, this book - which begins with the death of Henry VIII and ends with the accession of Elizabeth - aims vividly to bring to life three Tudor sovereigns: Renaissance princes, certainly, but in the final analysis people not so very unlike ourselves.

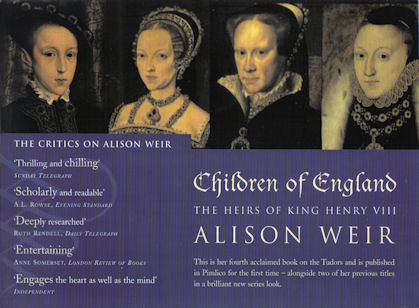

Above: Rejected U.K. jacket. The portraits are supposed to be of Edward VI, Lady Jane Grey, Mary I and Elizabeth I, but the lady shown top right is Katherine Parr! When this book was published, the portrait that replaced Katherine's (above right) was thought to be Lady Jane Grey. It has since been established that the sitter is Katherine Parr.

From the South Wales Argus, March 1996:

"I feel that women have a more emotional view on things than men. Perhaps it’s because we bear the children and have a different biological role. Men tend to gloss over details."

Seeing things from a woman's perspective is very much at the forefront of Alison Weir's mind. The 45-year-old author, who is married with two children,writes popular history and concentrates on the Tudor period. Since writing her first book at 15, so far she has had four books published, and is busy writing her fifth, on the private life of Elizabeth the FirsL

On top of this, Alison has started her own school for special-needs children, after being unhappy with the state education being provided for her 14-year-old dyspraxic son, John.

"I teach during the day which gives me great fulfilment, and I write for two hours every evening," she said. "I write one chapter a week and it takes me about six months to write a ook."

Instead of basing her writing on the male characters, the battles and the politics, Alison, who lives in Surrey, takes a different and, she contends, a female slant.

"I'm interested in real life, the real people," she said. "I think they are the interesting bits of history."

Her fascination with history began at the age of 14 with Katherine of Aragon, first wife of Henry Vlll, which turned into a fascination about the King and his wives in general. She wrote her first book, about Anne Boleyn, at the age of 15 by taking data from history books and compiling it.

Her interest in Henry and his complicated marital affairs stayed with her; while studying for her A-levels, she began to build up an impressive amount of historical data on the Tudor monarch.

"I suddenly realised I had enough data for a book," said Alison. "But I just left it."

Alison went on to college, where she studied history as part of her teacher training course. After college she worked as a civil servant in London, where she met and married fellow civil servant Rankin, and the couple have two children, John, who is now 14, and Kate,12. It was while Alison was at home after giving up work to look after her children that she decided to dig out her research and do something with it.

"I realised it was too long ever to be accepted, and so I took a piece out of it on Jane Seymour and sent it away," she said. "It was rejected for being too short! But the publisher put me in touch with a literary agent, and he produced my first book."

In 1987 her first book, Britain's Royal Families, was accepted and was published in 1989. Seeing her work on the shelves lor the first time was an "incredible" experience for Alison.

"It had been just a hobby for so long,” she said. "Then there it was, on the shelves for people to buy. I wouldn't have minded not receiving a penny, it was just the recognition."

Alison continued writing, and in 1991, published The Six Wives of Henry Vlll. The following year saw the publication of The Princes in the Tower, and in 1995 Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses emerged.

Her work has received critical acclaim: one reviewer described 'Henry' as "as reliable and scholarly as it is readable"; another called it "an entertaining account... full of interesting detail... beguiling". Her children, however, are completely non- plussed with their Mum's success, says Alison, "I came in one day with my Henry Vlll book and showed it to my son. He just said: 'Excuse me mum, I can't see the television'!" Her husband Rankin still works as a civil servant, and, Alison admits, has not read any of her books. "He's more into the Second World War era," she laughs. She also admits to being a perfectionist, and says she researches fanatically for each book.

"I probably drive people mad, I'm extremely busy," she said. "But my work gives me great fulfilment, and my family drive me."

Writing history from a female slant is something that comes naturally to Alison.

"Men tend to write about the battles and the politics and gloss over the personal details," she said. "I like discovering the people, especially the women. I find the personal details fascinating, like their experience of childbirth or, as with Elizabeth I, the reason behind her refusal to marry. Women writers and readers want to know these details and enjoy dealing with the minutiae of everyday life."

Alison says she is never tempted to add her own version of history to her books. "I get all the facts first, and research thoroughly and go with that," she said. "It makes me annoyed when people make assumptions about what happened without anything to back them up."

Although she has worked strictly with facts for most of her life, Alison has also been trying her hand at fiction - the novel she's writing has been progressing for years, and is worked on during family holidays and time off.

As for the future, she admits to taking nothing for granted.

"If it stopped tomorrow, I'd think, that was wonderful, I've had my chance," she said. Meanwhile, she continues to write, and encourages others to take her lead.

"I'm always encouraging people to write," she said. "If you have a talent, don't give up on it. After all, I was 37 when my first book was accepted."

MARY I'S PHANTOM PREGNANCY

A professional opinion from Michael Cameron, formerly Senior Consultant in Obstetrics and Gynaecology, St Thomas's Hospital, London; sent to the author in 1995. I had suggested that Mary's phantom pregnancy was caused by a hydatidiform mole, or that her child died inside her.

As general background, the incidence of hydatidiform moles in this country is about 1 in 500 pregnancies, so though it is not common, nor is it very uncommon. The condition is much more common in certain other parts of the world - Nigeria, Iran, the Philippines. It is caused by a chromosomal iregularity and is abnormal from its inception. The condition is as you describe it except for one point, which is that it is the placenta that develops like a bunch of grapes and is eventually expelled. Mr Cameron thought it unlikely that Mary I had such a mole, for two reasons. First, the expulsion is always accompanied by bleeding, sometimes very heavy bleeding. Secondly, expulsion only rarely occurs later than three to four months after conception, and almost never later than five.

On the question of whether Mary suffered an intra-uterine death - the death of a viable foetus, or a late abortion - probability is against this. Again, bleeding is bound to have occurred whenever the foetus was delivered, and there is no question of it having dissipated in the uterus.

Realistically, for either of these conditions to have occurred, someone, and Mary herself, must have lied about the bleeding, as well as the timing in the case of a mole. This seems unlikely if one looks at the available evidence and Mary's known integrity.

On the strength of the evidence, Mr Cameron felt that the symptoms presented - as far as we can evr know them - add up to a number of possible contributory factors. First, given Mary's health history, both physical and psychological, and her appearance, she is quite likely to have believed that she had become pregnant when the first missed periods of an early menopause manifested. This might have resulted psychosomatically in the other symptoms of a phantom pregnancy, like distension and early breast milk, developing, since a pregnancy was from every point of view so desperately important to her. Nowadays the question of whether a pregnancy is genuine or not is easily settled by a scan, which is presumably why the condition has become so rare, but in Tudor England it would have been considerably more difficult to diagnose, particularly as doctors wouldn't, for reasons of etiquette, have been allowed to examine the Queen thoroughly, and probably wouldn't have known how to anyway.

Distension in phantom pregnancy is caused by gas, and gas can dissipate at any time, which would account for Mary regaining her waistline. Her subsequent depression and the fact that she ate very little in pregnancy - possibly suggesting that she suiffered a spell of anorexia, which would also have produced distension - might well have held off the resumption of her periods until August, when she had to accept that it had all been a mistake. Mr Cameron pointed out that anyone who has a history of irregular periods is far more likely to produce unusual gynaecological symproms under pressure than a person without such a history.

TWO NEWLY DISCOVERED PORTRAITS OF ELIZABETH I AS PRINCESS

In 2008, I and Tracy Borman discovered a hitherto-unknown rare portrait type of Elizabeth I before her accession. Our findings were published in BBC History Magazine in June that year, and attracted much media interest. Below, you can read the full, unpublished text of my research on these important portraits; it was this text on which the much shorter magazine article was based.

Portraits of Elizabeth I surviving from before her accession in 1558 are very rare. Only six can be said with a degree of certainty to portray her. She appears at the age of about seven or eight in the Henry VIII family group painted by an unknown artist around 1544-5 and now at Hampton Court (top left). There is a fine three-quarter-length portrait of her at Windsor Castle, wearing a rose damask gown (top centre-left); this is recorded in Henry VIII`s inventory in 1547, and was probably painted in c1546, perhaps by the court painter William Scrots. Then there are versions at Syon House in Middlesex (top cente-right), Audley End (top right), Essex, Gardner Soule and (formerly) the Berry Hill Galleries in New York (bottom left) of a later portrait, in which the sitter – who is painted full-faced - wears the sombre garb of a virtuous Protestant maiden, attire that Elizabeth famously affected during her brother Edward VI`s reign; these probably date from the early 1550s. The Syon House portrait has traditionally been called Lady Jane Grey, but Sir Roy Strong identified it as Elizabeth in 1969. The costume is of a later date than that which Lady Jane would have worn. Related to these is a portrait, probably painted around the time of Elizabeth`s accession in 1558, at Hever Castle (bottom centre-right), also showing her full-faced, and this in turn has similarities with a miniature of Elizabeth in coronation robes, which dates from c1559 to the 1570s, in the collection of the Duke of Portland (bottom centre-right). A later, inferior version of this, as a panel portrait, is in the National Portrait Gallery (previously at Warwick Castle) (bottom right).

Essentially, then, there are four known portrait types of the Lady Elizabeth, as the Queen was known prior to her accession. (She was not styled Princess after 1536, because that year, in the wake of her mother Anne Boleyn`s fall, she was declared illegitimate.)

There is, however, another important image. At Boughton House, Northamptonshire, in the private collection of the Duke of Buccleuch, hangs a virtually unknown painting, which is not on public display and has never before now been reproduced (below, top). Nor has it ever been subject to any scrutiny by historians or art specialists. Furthermore, there is very little information about it in the Buccleuch inventory. But this picture incorporates an important image of Elizabeth I as a teenager, which is not only an exciting find in itself, but also has strong similarities to a portrait of an unknown lady in the National Portrait Gallery that may also be of her (below, bottom right).

The work in question, the original of which is by an unknown follower of Holbein and Scrots, shows Henry VIII and his three children, with Will Somers, his famous jester, standing in the background. Internal evidence would suggest that this picture – or its lost(?) original, for this may be a copy – was painted towards the end of Edward VI`s reign, in the early 1550s. This is indicated by the fact that the boy King is shown in the centre of the picture, and that his figure is larger than those of his older sisters, so he must have been on the throne at the time; and his image is based on the documented portraits executed by the court artist William Scrots around 1550-52, of which many copies exist (below left).

To the left appears Edward`s father, Henry VIII, whose figure is based upon the final portrait type of the King, attributed to Hans Holbein and painted around 1543, the key example of which is at Castle Howard in Yorkshire (above right). In the Boughton picture, Henry wears similar costume and has the same pose, grasping a staff in his left hand and a glove in his right. He looks older and more white-haired than in the Holbein painting.

To the right of the Boughton picture are Henry`s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. The image of Mary is based on no known likeness, although there are similarities to other portraits of her; this picture of her is also a significant find, because there exists no other portrait of her dating from the latter half of Edward`s reign. The image of Elizabeth, however, bears a striking resemblance to a small circular portrait of a young lady in the National Portrait Gallery (NPG 764) that used to be called Lady Jane Grey. Both wear almost identical costume; there are strong similarities in the jaw, mouth and nose, and if the eyes and hairline differ slightly, this may well be due to the fact that NPG 764 is heavily overpainted. This all suggests that the Boughton Elizabeth may derive from NPG 764 or another version of it, and that this was a known portrait type of the princess.

NPG 764, which is six-and-a-half inches in diameter, was identified as Lady Jane Grey in 1887, when it was purchased from a Miss A.A. Coulton of Stalybridge, Manchester. It was believed to have come from nearby Aston Old Hall, and had been bought by Miss Coulton`s father in Stalybridge as a portrait of the young Mary I. It was known as Lady Jane Grey until 1963, when Sir Roy Strong, in his Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I, suggested a link between this and other portraits of the young Elizabeth, but in 1969, in his Tudor and Jacobean Portraits, he stated that he was less inclined to support that identification. Since he did not mention the Boughton picture, with its striking likeness, in either book, it is unlikely that he had seen it. Nowadays, NPG 764 is called a portrait of an unknown lady.

There are other linked portraits of Elizabeth that bear similarities to both NPG 764 and the Boughton picture. As well as two drawings of c1560 in the portrait folios of the Receuil d`Arras (top left and centre), which almost certainly depict the young Queen, there is an engraving of c1559 by Franz Huys (top right), and the portrait at Hever Castle mentioned above, as well as two early miniatures of Elizabeth I by the court limner, Levina Teerlinc (bottom left and right).

There is also a different version of the Boughton picture, which, until recently was at Althorp, just five miles from Boughton, and is now in the collection of the Sarah Campbell Blaffer Foundation in Texas, where it is described as a posthumous sixteenth-century portrait of Henry VIII with Mary I and Will Somers by an English artist (above left). Like the Boughton picture, this is a composite portrait, but apart from the fact that Edward and Elizabeth are missing, there are major differences. Again, Henry is to the left, but his image derives not from Holbein`s last portrait of him, but from that artist`s earlier portrayal of the King, painted full-length as part of the famous lost Whitehall mural in 1536, of which only a copy survives (above centre). This was to become the most celebrated image of Henry VIII, the one that is best-known today, and it was the most powerful visual expression of the iconography of the New Monarchy and Royal Supremacy of the 1530s. Coming face to face with it in the presence chamber, where it dominated the room, observers would feel `abashed and annihilated`. It was effectively the first state portrait, and six full-length copies of it survive. Henry`s pose in the Boughton picture, however, differs from the Holbein pose, and the costume is unlike any in the known versions of the 1536 portrait. This might indicate that there were other, now lost, variations of Holbein`s famous portrait, which would not be surprising, given that there would have been a high demand for copies of it by subjects anxious to proclaim their loyalty to the new order.

The image of Mary in the Althorp picture is also based on a state portrait, the one painted by the Spanish artist Antonio Mor in 1554 (above right), of which three major versions exist (at the Prado, Madrid; Castle Ashby, Northamptonshire – previously, until the nineteenth century, at the Escorial, Madrid; and at the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston). There are other inferior versions, but this is one of the chief portrait types of Mary I, and its use as the basis for her figure in the Althorp portrait strongly suggests that that picture must date from the staunchly Catholic Mary`s reign (i.e. from 1554-58), a theory that is supported by the absence of the Protestant Edward VI and the politically and doctrinally suspect Elizabeth, who was out of favour for much of Mary`s time.

A major link between the Boughton and Althorp pictures is Will Somers, Henry VIII`s fool, who appears in both, and it may well be more than coincidental that these pictures once hung within five miles of each other in Northamptonshire, while Somers had links with the Fermor family who lived some ten miles south of Althorp at Easton Neston. Somers may well have commissioned both pictures. However, our painting was not at Boughton in the seventeenth century, when only six large portraits were recorded as hanging in the house. It may have been kept at one of the family`s other properties, Ditton in Buckinghamshire and Montagu House in London, and it could originally have come from Barnwell and Hemington, two houses in Northamptonshire that were owned by the Montagues, ancestors of the Duke of Buccleuch, in the sixteenth century, Barnwell being their chief seat. On the other hand, it may have been owned by someone else – Somers himself?- and only later acquired by Montagu`s descendants. The family`s greatest collector was Ralph Montagu, the first Duke of Montagu (1638-1709).

Somers appears as an older man in the Althorp picture. He is shown with receding hair in the Boughton painting of probably a few years earlier, but this has been replaced with a skull cap in the Althorp version. He has a little dog that does not appear in the Boughton picture, and he would appear to be grasping something, perhaps a staff, but this appears to have been painted out. In fact, the whole of the background is plain, and the canopy of estate that features in the Boughton picture is absent; it may also have been overpainted.

Tudor royal family groups were usually painted for propaganda purposes. That at Hampton Court (above, top) shows Henry VIII enthroned in Whitehall Palace, with his heir, Prince Edward and Edward`s mother, Jane Seymour, who appears posthumously; beyond the two pillars framing this central group, stand, on either side, the King`s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, their positions outside the inner circle reflecting their bastardy. Both this picture and Holbein`s lost Whitehall mural, referred to above, which depicted Henry VIII and Jane Seymour with the King`s parents, Henry VII and Elizabeth of York, were commissioned to make important dynastic statements about the Tudor dynasty and the New Monarchy of the Reformation. Similarly, in Elizabeth`s reign, a painting of c1572 attributed to Lucas de Heere (above, bottom left) depicts Henry VIII with Edward VI kneeling beside him, with Mary I and Philip of Spain attended by Mars, the god of War, and Elizabeth I bringing with her the goddesses of peace and plenty. This is no cosy family portrait, but an allegory of the Tudor succession, and it was sent by Elizabeth herself to her ambassador in France, Sir Francis Walsingham, probably in the wake of the St Bartholemew`s Day massacre, as a `mark of her people`s and her own content`, as the inscription shows. Another family group, showing Henry VIII, Edward VI and Elizabeth I, dated 1597 and now in the Art Institute of Chicago, bears the inscription: PROFESSORS AND DEFENDORS OF THE TRVE CATHOLICKE FAYTHE (bottom right).

This all begs the question: were the Boughton and Althorp groups painted to make a political statement? The answer is very likely yes. It is possible that the Boughton group was commissioned by Somers to depict the Tudor succession and his own links to the royal House. Yet Boughton was bought in 1528 by Sir Edward Montagu (d.1557) (the present Duke of Buccleuch`s ancestor) in the sixteenth century. Significantly, Sir Edward, a Privy Councillor, was one of the commissioners of Henry VIII`s Will, which left the crown to Edward, Mary and Elizabeth in turn, and he was later a member of Edward VI`s regency council and in 1553 helped to draft up Edward`s will, which altered the succession in favour of Lady Jane Grey. It is possible that Montagu was instrumental in commissioning the Boughton picture – although that would not explain Somers` inclusion in it - or that Somers commissioned it for presentation to him.

Several years later, when Mary was on the throne and England had turned Catholic, it was no longer desirable to portray Edward and Elizabeth (whose religious views and ambitions were distrusted by the Queen), so it is possible that Somers commissioned a second picture, the Althorp version, showing himself loyal to Mary and with the father whose memory she and Somers both revered; here, Henry appears at the height of his powers, as if to emphasise Somers` links to greatness – and perhaps the way Somers now preferred to remember him.

These are not the only portraits we posses of Will Somers. He appears in an illustration in King Henry`s Psalter of c1540-42, in which he stands listening as Henry VIII, in the guise of King David, plays the harp (bottom left); and he is almost certainly the man with a monkey standing in the doorway to the right of the Whitehall family group (see above); the lady in the left doorway is thought to have been one of several female fools who served the royal family, perhaps `Jane the Fool`, who was employed by the future Mary I. Thus a precedent was set for the inclusion of fools in royal family groups, which Somers may have borne in mind when including himself in the Boughton and Althorp pictures.

There is an engraving of the Boughton picture (above right), which was done by Francesco Bartolozzi of Florence (1727-1815), a prolific Italian engraver who had assisted Richard Dalton, George III`s Librarian, with the acquisition of new works of art before being invited to London in 1764, where he remained for the next 40 years under the King`s patronage. He appears in John Zoffany`s group portrait, The Royal Academicians, painted in 1771-2. Between 1792 and 1800, Bartolozzi executed a number of engravings of Holbein’s drawings at Windsor, including the one of Edward VI. There is no record of his visiting Boughton or Northamptonshire, but an artist under royal patronage would have enjoyed an entrée to the houses of the nobility and access to their private collections. The Boughton picture would no doubt have been thought worth engraving because of its famous sitters, and his familiarity with the Royal Collection over many decades would have ensured Bartolozzi`s recognition of the importance of the picture.

While the Althorp picture is better known, it has never been the subject of serious research, and neither has the Boughton picture, which, important though it is to our knowledge of Tudor royal portraiture, is virtually unknown. Until it is studied by art experts and the panel is subject to dendrochronology, we cannot establish whether or not it is an original of the early 1550s or a later copy of a lost original. The Boughton painting shows poor draughtsmanship, of the kind associated with itinerant limners who painted copies of famous portraits for the owners of country houses to hang in prominent places such as long galleries, to demonstrate where their political loyalties lay. In the late 16th/early 17th centuries, it was fashionable to have long gallery sets of portraits of kings and queens, which is why there are so many copies of (often lost) originals in the royal and other collections. The Boughton picture almost certainly is a copy, probably of the 17th century, given the treatment of the drapery, but even if it is, it is valuable in that it provides us with a new image of the young Elizabeth that is related to NPG 764 and other portraits, which strongly suggests that NPG 764 is also an early portrait of Elizabeth.

Select Bibliography

George III and Queen Charlotte: Patronage, Collecting and Court Taste (ed. Jane

Roberts, Royal Collection Enterprises, 2004)

Roy Strong: Gloriana: The Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I (London, 1987)

Roy Strong: Portraits of Queen Elizabeth I (Oxford, 1963)

Roy Strong: Tudor and Jacobean Portraits (2 vols., HMSO, 1969)

Dictionary of National Biography

MISCELLANY

I have received several complaints from American readers claiming that the U.S. title of this book, The Children of Henry VIII, is incorrect, as the story encompasses Lady Jane Grey also. As Newsday shrewdly guessed, ''This misleading title must have been dreamed up by some marketing genius who thought that the title of the Britsh edition wouldn't sell in the United States." Indeed it was, and although I protested about it at the time, the decision was beyond my control.

For a long time, I - and many other historians - assumed that the name of Elizabeth I's governess was Katherine (Kat) Ashley, but after Children of England was published, a descendant of the family wrote to me to say that the correct spelling was in fact Astley.