Books

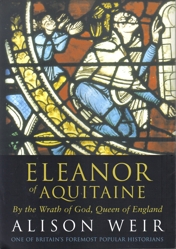

Eleanor of Aquitaine, By the Wrath of God, Queen of England/Eleanor of Aquitaine: A Life (1999)

Eleanor of Aquitaine is my best-selling book to date.

It was the winner of the Good Book Guide award for the best biography of 1999, as voted for by readers in 100 countries.

It is the sixth best-selling historical biography of all time in the U.K..

"An alluringly candid portrait of this most public yet elusive woman… A truly epic landscape of twelfth-century Europe in all its blood and glory." (The Boston Globe)

"Triumphantly done." (Frank McLynn, The Sunday Times)

"Weir approaches Eleanor`s story with an objective eye and a mass of source material. The result is as vivid as it is informative." (The Times)

"Evocative…A rich tapestry of a bygone age, and a judicious assessment of her subject's place within it." (Newsday)

"Lively biography." (The Sunday Times)

"The extraordinary life of Eleanor of Aquitaine is brilliantly recreated by Alison Weir in her winning biography." (The Good Book Guide)

"As delicately textured as a twelfth-century tapestry, Weir`s book is exhilarating in its colour, ambition and human warmth. The author exhibits a breathtaking grasp of the physical and cultural context of Queen Eleanor`s life. Her account parades a sequence of extraordinary characters... Above all, there is the heroine, viewed clear-sightedly in all her intoxicating and imperious irresistibility." (Publishers Weekly, starred review)

"Alison Weir meets a subject well-worthy of her mettle…her exciting story merits our attention." (BBC History Magazine)

"An extraordinary book about an extraordinary woman." (Derby Evening Telegraph)

"A scholarly as well as fascinating study." (John Jolliffe, The Spectator)

"Impressive…Weir manages to breathe life into her subject." (Petronella Wyatt, The Spectator)

"Evocative... A rich tapestry of a bygone age and a judicious assessment of her subject's place within it." (Newsday)

"Weir provides the necessary checks and cautions against believing all we read, whilst enjoyably recording the gossip anyway... Weir gives us a balanced account, with myths, suppositions and misunderstandings well-ventilated." (The Literary Review)

"Alison Weir clears the cobwebs with a fresh biography of a remarkable woman." (Irish News)

"Alison Weir`s exciting and astringent account debunks many of the legends surrounding Eleanor. Acute psychological insight combined with rigorous research has produced a rounded and satisfying picture of an extraordinary woman." (The Tablet)

"Woven with great skill and cunning detective work into a vivid and haunting portrait." (Ms London)

"When you finish the book you feel you have been put painlessly (but not necessarily without tears) in possession of the facts about this extraordinary, indefatigable woman." (The Spectator)

"Alison Weir`s achievement is to flesh out this remarkable woman from the dry pages of the chronicles and bring to life these turbulent times." (The Mail on Sunday)

"The author's well written pages - as in her previous books- lead easily to a rich, deep and accessible understanding of the topic." (Booklist)

"This is readable history at its best and a fascinating insight into the mediaeval mind." (South Wales Evening Post)

"The book reads like a mediaeval legend…clear-sighted and interesting." (Dundee Courier and Advertiser)

"Weir`s rendering of events is valuable as a revision of earlier biographies…detailed and convincing…impressive in its breadth and clarity…[A] cogent and fascinating book." (Joanna Laynesmith, The Times Higher Education Supplement)

"Weir weaves a fascinating tale without embroidering…Anyone intending to read any kind of saga or romance would find this impressively organised history far more rewarding than fiction." (The Evening Standard, Paperback of the Week)

"Alison Weir has written a vivid biography which is also an impressive piece of detective work, for she has scrutinised the evidence to produce a credible and balanced account of the life of an extraordinary woman." (The Sunday Telegraph)

"A book with the pace, verve and readability which has become [Weir`s] hallmark." (The Good Book Guide)

"Weir is so much the master of the period, so intuitive and unsentimental an interpreter of royal minds, and so upfront in her assumptions that I trusted her completely." (The Boston Globe)

"Alison Weir's riveting biography draws readers into the rich, intricate world of the early medieval period." (Fort Worth Morning Star)

"An outstanding account, full of insights, some scandals, and above all a fully-realised portrait of the woman who has been called 'the grandmother of Europe'." (The A List)

"This book doesn't read as history; this book is history." (Chicago Public Libraries)

"This book strips away much of the myth. It reads like a medieval legend. This is readable history at its best, and a fascinating insight into the medieval mind." (Northern Echo and various other local papers)

"Weir weaves a fascinating tale without embroidering." (Yorkshire Post)

"A fascinating work that proves to be a real page turner." (Nuneaton Evening Telegraph)

"A vivid picture of a grand dame." (Bridlington Free Press)

"Intelligent, compelling history is what Weir does. It doesn't get any better than this." (Venue)

"Invaluable to anyone with an interest in medieval history. A fresh and provocative biography." (Executive Woman)

"An impeccably researched historical biography." (Kirkus Reviews)

"In the sweeping pageant of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Weir convincingly debunks some of the more salacious fables about Eleanor's libertine ways." (The Boston Globe)

"Alison Weir paints a vibrant portrait of a truly eceptional woman, and provides new insights into her life." (Koen Pacific)

"Alison Weir has succeeded in bringing one of history's most formidable women to life once more to dazzle a new generation of readers." (The History Review, Waterstone's Booksellers)

Eleanor of Aquitaine will be published as a beautifully bound limited edition by The Folio Society in 2015, with new colour illustrations.

Random House UK Newsletter, 2000

I am delighted that Random House has decided to publish a newsletter to coincide with the publication of Eleanor of Aquitaine in paperback. For some time now, a growing workload has made it increasingly difficult for me to reply at length to all the kind and thoughtful people who take the trouble to write to me; this newsletter will enable me to keep in touch with them, and with many other people who read my books.

Firstly, a little bit about me. I am a Londoner, born and bred, although I have also lived in Norfolk and Sussex, and now reside in Surrey. I have been married to Rankin for twenty-seven years, and have two children, John, aged 17, and Kate, 15. Before becoming a published author in 1989, 1 was a civil servant, and then a full-time housewife and mother. Because my son has learning difficulties and we could not find a suitable school for him in our area, I educated my children at home from 1991 to 1993, and then from 1994 to 1997 ran my own school for children with special needs - while at the same time researching and writing my books. There were times when I felt I should give up sleep in order to get everything done!

I have been interested in history since the age of fourteen, when I read my first adult novel: a rather lurid book entitled Henry's Golden Queen. I was, however, enthralled by it: did people really go on like that in Tudor times, I asked myself, and dashed off to find some real history books - in which I learned that, yes, they did! My passion for history was born. By the time I was fifteen I had produced a reference work on the Tudor dynasty, a biography of Anne Boleyn and several historical plays, and had started work on the research that would one day take form as my first published book, Britain's Royal Families.

During the 1970s, I wrote the original version of The Six Wives of Henry VIII - 1000 pages long, single spaced, and typed on both sides of the paper - and had it rejected on the grounds that there was a world paper shortage! I also researched the lives of all the medieval queens of England, research which I have since drawn on for several of my books and for Eleanor of Aquitaine in particular. I finally found a publisher in 1988, but am still pinching myself to make sure I'm not dreaming it all. Since then, I have published seven books and am now hard at work on the eighth. But more of that later.

I write popular history. This term is sometimes used in a slightly derogatory sense by certain academics, yet there is no good reason for it. I have no axe to grind against academic historians: authors like myself owe a great debt to them and their excellent researches. Yet history is not the sole preserve of academics; it belongs to us all and can be accessed by us all; in that sense, it can be popular. Very many people have a great love of history, and if the recounting of deeds past in a conscientious and accessible way brings them pleasure, then I account my task well done. Moreover, in an age in which history is often perceived to be 'dumbed down', I feel strongly that we can all learn from a study of the past. We can discover more about ourselves and our civilisation and make more informed decisions about the future.

Above all, history is full of the most riveting stories. I have often been told that my books read like novels, but I assure you that there is nothing made-up in them. The truth as they say is always stranger than fiction, and nowhere does this become more apparent than in history books. I can never understand, therefore, why the makers of historical films feel they have to change the facts.

One of the most fascinating stories in history is that of Eleanor of Aquitaine. I have always found her an enigmatic and elusive figure, and writing her biography was a labour of love - something I had wanted to do for over a quarter of a century. Most of my research was done in the 1970s, when I transcribed thousands of references to the medieval queens of England from chronicles in the Rolls Series and other contemporary sources. This huge bank of material lay forgotten for years until a reader wrote begging me to write a book on Eleanor. This inspired me to look again at the research, and I realised that it had the makings of a wonderful project. All that remained was to convince my publishers of this. However, after the success of Elizabeth the Queen, the time was right for me to write a book about another strong and independent woman in history.

Eleanor of Aquitaine has far outsold my expectations, and I suspect that there are many people who brought the book on the strength of her reputation alone. On the promotional tour, I met many with a keen interest in her and I have since received numerous letters from readers who are very well-informed. Many are intrigued to discover how I researched the book, and several of those who attended my events raised controversial issues, such as Eleanor's extra-marital affairs or Richard I's sexual inclinations. To all those who came to my talks or who wrote to me, may I say it has been wonderful, and highly enlightening, to have had the chance to discuss Eleanor with fellow enthusiasts. I am very much looking forward to the promotional tour for the paperback.

At present I am just completing the research for my new book, Henry VIII: King and Court, which is scheduled for publication in June 2001. In this book I mean to present a detailed and comprehensive study of Henry VIII set within the context of what was undoubtedly the most magnificent court in English history. The book will focus on the personal life of the King and the lives of his courtiers, and will encompass every aspect of Tudor court life, from state banquets to sanitary arrangements, and from Renaissance influences to amorous intrigues. There will also be a few surprises concerning Henry's private life!

After this, my next project will be Mary, Queen of Scots, and the Murder of Lord Darnley. When I was researching Elizabeth the Queen, most of the sources I read led me to the conclusion that Mary, Queen of Scots, knew in advance of the plot to murder her husband, Lord Darnley. However, it was felt by my publishers that this was so controversial an assertion that it should be the subject of a separate book, in which I will use the same research and analytical techniques that I used for an earlier historical whodunnit, The Princes in the Tower. I am therefore keeping an open mind on the subject until I see what the research reveals. I am really excited at the prospect of researching and writing another historical mystery - they are my favourite kind of books.

I may not be able to reply to all your letters personally but I am always touched that readers take the trouble to write to me. I can only say a heartfelt thank you for all the positive comments, and welcome the new opportunity to share my enthusiasms with readers, which the Newsletter affords.

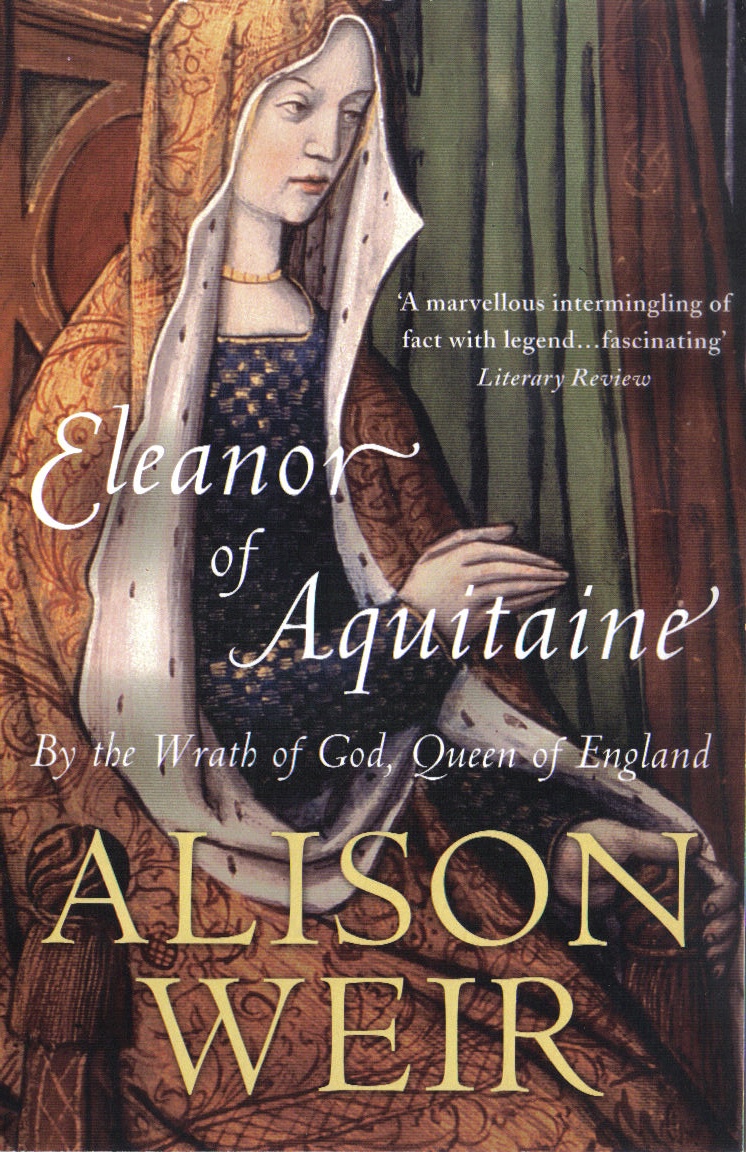

Rejected U.K. (top) and U.S. (bottom) jackets. The painting of Eleanor of Aquitaine (bottom centre) was specially commissioned for the American paperback, but I felt that such an image would not be appropriate for non-fiction.

The photograph above was sent to me in 1999 by a reader. These heads, from the porch of the twelfth/thirteenth century church of Candes St Martin, between Chinon and Fontevrault, are thought to represent Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine, and date from c.1225.

WHY ELEANOR WAS A GREAT QUEEN

In 1189, when King Henry II died, his Queen, Eleanor of Aquitaine was released after sixteen years of imprisonment. Her custodians, bearing in mind the love that the new King, Richard the Lion Heart, had for his mother, and his fearsome reputation, had not demurred when this grand old lady demanded to be set free. Soon, people were rushing to pay their respects, and King Richard sent word that Queen Eleanor was to be entrusted with the power of acting as regent until his return from Normandy. Indeed, he issued a general edict to the princes of the realm, that the Queen’s word should be law in all matters.

Eleanor now came into her own. At 67, a great age in the twelfth century, she emerged from captivity an infinitely wiser woman, her dignity and her prodigious energy undiminished.

As sovereign Duchess of Aquitaine, she was the greatest heiress in Europe, having inherited the southern half of what is now France at the age of fifteen. She had been the wife of two kings, Louis VII of France – whom she divorced – and Henry II of England; and the transfer of her domains on marriage, first to France and then to England, set the pattern for European diplomacy and warfare for the next four centuries.

Eleanor was beautiful, spirited and adventurous. Gossip about her love affairs, and her conduct on crusade, was widespread, and in her younger years she had acquired a colourful reputation. Her marriage to Henry II saw the establishment of a great Plantagenet empire, but their early passion gave way to a stormy and tempestuous relationship. When their sons grew to maturity and Henry would not delegate power to them in the territories he had assigned them, they grew angry and resentful, and Eleanor – like Matilda of Flanders in a similar situation - took their part. In 1173, she joined them in a rebellion against their father, which plunged Henry into the worst crisis of his reign. For him, this was a terrible betrayal on the part of his wife. When Eleanor, wearing men’s clothing, was arrested on her way to Paris, where she planned to seek the support of her former husband, King Louis, Henry had her shut away for a year, then took her to England, where she spent the last fifteen years of his reign mainly confined at Old Sarum or Winchester. Clearly, he knew her to be a force to be reckoned with – and never trusted her again.

But now Henry was dead, and the love and loyalty of her son, the new King, vindicated the stand and the sacrifices she had made on his behalf. Eleanor’s new authority sat easily upon her. More powerful than ever before, she was willing and eager to grasp the reins of government and exert her benign influence over Richard, who would need all the help he could get to rule an empire that stretched from the Scottish border to the Pyrenees.

During the first half of Richard’s ten-year reign – for much of which he was abroad - Eleanor was, after him, the chief power in the realm. It is on these, and her later years, that her towering reputation chiefly rests. She began by drumming up support for Richard in England, where he was barely known. She made every freeman swear loyalty to him, and herself received all their oaths of allegiance. She reconciled warring lords and churchmen. She married off heiresses who were royal wards to men known to be loyal. She travelled the kingdom extensively, dispensing justice and receiving homage, and the nobles obeyed her unhesitatingly, aware of her formidable reputation. She personally transacted the business of court and chancery, using her own seal on official documents. She issued edicts ordering that weights and measures were to be uniform, and that a standard coinage, valid everywhere in the land, was to be issued; these were just and fair measures that benefited trade enormously.

Eleanor was a strong woman, but she was compassionate too. She founded a hospital for the poor, the sick and the infirm. She ordered that anyone who had been unjustly imprisoned should be released, so long as they promised to keep the peace, for she had found by her own experience that to be released from prison was ‘a delightful refreshment to the spirits’. When visiting lands near Ely, which had been laid under a temporary interdict, she was appalled to see human bodies lying unburied in a field because their bishop had deprived them of burial. She visited the cottages of the wretched villagers, comforting them in their grief at being deprived of the sacraments of the Church, and listening with feeling to their accounts of the miseries they had endured. She took pity on them, ‘for she was very merciful’. Immediately dropping her own affairs, she went to London and prevailed upon the Bishop to revoke the interdict.

Eleanor was unusually sensitive, for her time, to the privations suffered by the poor. She commanded that the harsh and hated forest laws should be relaxed, and pardoned felons who had been caught trespassing or poaching in the royal forests. She curbed the depredations of the sheriffs who were charged with care of the forests, and who had enforced these cruel laws, intimidating them with the threat of severe penalties. She revoked Henry II’s order that relays of royal horses be stabled at monasteries at the expense of the latter, which had crippled the less well-off houses; and she presented the horses as gifts to the abbeys.

Eleanor was also zealous to see justice done. Once, learning that the knights and tenants of Abingdon Abbey had failed to provide time-honoured service to their abbot, she wrote commanding them to comply. ‘And if you do not do so,’ she added, ‘then the King’s justice and my own will make you do so.’

Eleanor’s wise and far-seeing measures would have had a highly beneficial impact on the lives of ordinary people, and they were universally welcomed, especially by the poor. In her every act, she displayed ‘remarkable sagacity’, ruling England ‘with great popularity’, and demonstrating all the qualities of a wise, benevolent and statesmanlike ruler – which she had never until now had the chance to exercise fully, but which suggest that, had she been a queen regnant like Elizabeth I, and not merely a queen consort, she would have governed with strength, wisdom and mercy, and even excelled Elizabeth’s abilities and reputation. One cannot imagine Eleanor of Aquitaine leaving the brave sailors who had fought in the Armada to starve in the streets.

Certainly Eleanor’s contemporaries were deeply impressed; even the highest in the land deferred to her authority, and after her death it was recorded that her rule had made her ‘exceedingly respected and beloved’.

Eleanor was unstoppable: age did not quench her. It was said that she was still ‘indefatigable in every undertaking, although advanced in years; her power was the admiration of her age’. She was ‘unwearied in any task, and provoked wonders by her stamina’. In 1191, she travelled to Spain to fetch a bride for Richard, and escorted her to Sicily to meet her bridegroom. When Richard I was a prisoner of the German Emperor after failing to recapture Jerusalem in the Third Crusade, it was Eleanor who was tireless in raising the King’s exorbitant ransom, and Eleanor who travelled to Germany to hand it over and be reunited with him. It was Eleanor who reconciled her sons, Richard and the treacherous John, on their return. Although she retired to the Abbey of Fontravraud in 1194, she kept her finger on the pulse of European affairs. At the age of 78, she crossed the Pyrenees once more to fetch another bride, her granddaughter Blanche of Castile, and convey her north to marry the heir to France. At 80, she defended the castle of Mirebeau against the forces of her hot-headed nephew, Arthur of Brittany.

In these years, Eleanor was described as still beautiful, gracious and chaste’. She was at once ‘powerful and modest, meek and eloquent, strong-willed yet kind, unassuming yet sagacious, qualities that are rarely to be met with in a woman’. She was formidable too. When the Pope failed to press for Richard’s release from captivity, she castigated him for it, furiously opening her letter, ‘Eleanor, by the wrath of God, Queen of England…’

She died in 1204, easily, ‘as a candle in the sconce goeth out’. The nuns of Fontevraud recorded that, ‘by her renown for unmatched goodness, she surpassed almost all the queens of the world’. Like Queen Victoria, she could be described as the ‘grandmother of Europe’, for among her eleven children were three kings, while her daughters all married great princes. Unlike Victoria, who merely reigned, Eleanor ruled a kingdom.

Eleanor played a controversial role in her younger years, but her towering reputation rests largely on what she did in her later years. Denied for so long the exercise of power, for which she clearly had a natural aptitude, and relegated to a traditional female role which must have been stifling for one of her ability and intelligence, she finally tasted power at an age at which most of her contemporaries were either infirm or dead. Even today, a woman taking over the government at the age of 67 would be remarkable. Moreover, Eleanor proved, long before Elizabeth did, that a woman could rule as capably as any man. She was no shrinking violet, but a tough, capable and resourceful woman who effortlessly wielded authority over men in a male-dominated age, and won their respect. For her compassion, her strength of character, her wisdom and her statecraft, she was, as a contemporary chronicler admiringly stated, ‘an incomparable woman’, and she deserves to be accounted one of the greatest queen who ever ruled in these islands.

FROM THE SUTTON ADVERTISER, 15 JANUARY 1999

Historian and writer Alison Weir is giving a lunchtime lecture in the delightful surroundings of Whitehall Tudor house in Maiden Road, Cheam, next Saturday, on a subject close to her heart and mind. Weir, 47, a passionate and prolific writer of historical biographies, especially about women, is exploring the theme of Women of their Time.

She said: 'I believe that history is about people, not just Acts, wars or politics. It's about personalities. I enjoy exploring how everyday lives were lived. I like to try to get a sense of character, to feel as if the subject is really alive. The lives of women were often governed by everyday customs, the sort of domestic details that male historians have tended to gloss over.'

Weir, from West Street, Carshalton, has published several historical studies, Elizabeth the Queen (on Elizabeth I); Children of England (about Henry VIII's heirs); Lancaster and York (on the Wars of the Roses); The Princes in the Tower, The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Britiain's Royal Families (a geneological study of the royals). She trained as a teacher, but had been indulging her almost irrational love of collating information on historical figures from an early age, and when she decided to write full-time, it took more than a decade to get accepted by a publisher. Now, the mother of two is about to launch her latest book on the 12th-century Queen, Eleanor of Acquitaine, wife of both Louis VII and Henty II, heiress of half of France, and mother of Richard the Lionheart and King John.

'She was an amazing woman, dynamic, headstrong, even a bit impulsive. 'She was highly sexed, and had a number of scandalous love affairs, including incestuous ones, while she was married to Louis, who was too monk-like to satisfy her.' Other activities included accompanying her husband on crusades and surviving a Turkish siege. She took a fancy to the future Henry II, who was 19 at the time; she was 30. In 1152 they married and she subsequently bore eight children.

Weir said: 'When her sons grew up, she wanted her husband to recognise their status. When he refused, she led a rebellion against him. She was arrested in 1174 and kept in custody for 16 years.'

Eleanor was devoted to her sons. When Richard became king, and went away on crusades, she even took the reins of power and toured the dominions whipping up support for John (her other son) ahead of his accession to the throne.

Weir's other strong woman is Elizabeth I. In the course of research, she says, her subject comes to life, like a character in a novel. And when she talks about the woman she spent months on end trying to understand, she is very protective and defensive.

She said: 'I have come to admire most of my subjects. In fact, as each project draws to a close, I begin to get almost mournful. I don't want to let them go.'

Alison Weir is lecturing at Whitehall, Maiden Road, Cheam, from 12.40pm next Saturday January 23. She will also take part in the London Festival of Literature at Cheam Library in March.

You can listen to my podcast on Eleanor of Aquitaine here at The Shakespeare Life, with Cassidy Cash: https://www.cassidycash.com/eleanor-of-aquitaine-with-alison-weir/

THE ALISON WEIR INTERVIEW

by Kath Hill and Stephanie Hunt

From The History Review from Waterstone's Booksellers, Issue One, Christmas 1999

On a recent visit to Waterstone's Deansgate to launch her new book, Eleanor of Aquitaine, Alison Weir took the time to have a chat.

Having published seven books over a period of only ten years how did you become interested in history?

Well - and my daughter will cringe - it was mainly though reading historical fiction as a teenager, and to this day. It's a genre that's now extremely passe, in fact I've had a historical novel based around Lady Jane Grey in the pipeline for years. I've always had an interest in the characters from the past. At fifteen I wrote a biography of Anne Boleyn but concentrated so hard on it that I did not reach the required grade at 0-level in order to do my A-level in history! It's always been a hobby though, mainly through studying my family tree and progressing into an interest in genealogy.

Now that many universities and colleges are running women's studies and women's history courses do you feel that these still seem to be marginalised in everyday academia?

Women are still underestimated for their input in social and political history. They still need a higher profile. Much of written history still focuses on politics and battles. What interests me are the personalities, the minutiae of everyday life. What people ate and drank, behaviour at court and how this related to life for the individual.

Do you think then that this is why it is mainly men who write military and political history?

History is about people and that's what's being ignored. It's not simply a family tree. Where women are involved there's often a more human angle.

Having concentrated mainly in your work on the Middle Ages and Tudor periods, how far into recent history would you travel?

In 1981 I put forward an idea for a biography of the Princess of Wales but it was considered too short to be a commercial venture, and that people would lose interest in her! Now I feel, in the wake of recent tragic events, that it will be a long time before any writer can bring the proper objectivity to the subject - maybe in thirty years time I might look at it. I would love to do Queen Victoria but owing to the saturation of books on her life, that won't be yet. I would love to research all our women rulers all the way back, and not just the women... John of Gaunt would be fascinating - the time of Geoffrey Chaucer, the Hundred Years' War, the fierce and vibrant personalities, the sex and intrigue...

How do you feel about the recent prominence in best sellers Georgiana Duchess of Devonshire and The Gentleman's Daughter*!

I think it's fantastic - the balance is finally being redressed.

What do you read for pleasure?

Well I loved Aristocrats, and the television adaptation was wonderful, and although the genre's out of fashion I love historical fiction. Even when I'm not researching I like to read about other eras.

Talking of small screen adaptations what did you think of Elizabeth the film?

As it co-incided with my book Elizabeth the Queen the interest it inspired in the era was marvellous but I thought the film was just awful - so many historical inaccuracies. On the other hand Shakespeare in Love was fantastic, pure entertainment and so believable, but Elizabeth was disappointing for me.

In 1968 The Lion in Winter portrayed Eleanor of Aquitane played by Katherine Hepburn as the same 'strong' woman you seem to have found in you research.

Yes, Katherine Hepburn was perfect in the role. The Lion in Winter has its basis in fact. It was a stage play set at a time of dramatic tension within the Angevin family, a chance to explore relationships in depth. Incidentally, Hollywood is about to remake the film casting Anthony Hopkins as Henry and Meryl Streep as Eleanor - to which I am greatly looking forward.

Finally, there is always talk in the media of suitable role models for girls. Eleanor of Aquitane was a strong capable woman and the grandmother of kings, might she fill the gap ?

Absolutely. She was scandalous as a young woman, but an absolute inspiration who showed just what a woman can achieve, and what you can do at 67!

U.S. INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, 2000

Was there anything in the writing of The Life of Elizabeth I that made you naturally turn to Eleanor as your next subject?

There was nothing as such in the writing of Elizabeth I, but I felt its success opened the door to my writing a biography of Eleanor, an idea I had been trying to sell to my publishers for about eight years! I enjoy writing about strong, charismatic women, and Eleanor was, I felt, an ideal choice.

There have been some marvelous movies made about Henry II - Becket (starring Richard Burton and Peter O'Toole) and The Lion in Winter with Katharine Hepburn and Richard Harris. Had you seen either of these films when you started work on the book, and if so, how well do you think they represented the historical players?

I first saw Becket and The Lion in Winter on their releases in 1964 and 1968 respectively; I own the video of The Lion in Winter, which I have seen several times, but Becket is not available on video in the U.K., although I used to have a long-playing record of it. I am therefore very familiar with both, and they are great favourites of mine. Given the dramatic licence inherent in any historical dramas, I would say that both films are legitimate treatments of their subjects, if not in the letter, certainly in the spirit. Katharine Hepburn's portrayal of Eleanor is masterful, as is Peter O'Toole's portrayal of Henry II in both films. Richard Burton made a superb Becket. I am not so sure about Richard I being portrayed as a homosexual, because there is very little evidence that he was. Nor do I think that John was the backward idiot portrayed in The Lion in Winter. However, the treatmnent of Alys of France is probably very perceptive. And, yes, Eleanor was allowed out of custody to spend Christmas with her family, although we have no record of what went on between them all. James Goldman has set his screenplay in an appropriate historical context and used the known facts to weave a credible tale. If you haven't seen these films, see them now! They don't make them like this any more!

You say in your introduction that this book 'felt more like a piece of detective work than a conventional historical biography'. Can you give us a few examples of snooping? Anything that doggedly eluded you?

For me, 'snooping' meant trawling through piles of ancient chronicles and modern books in order to extract as many snippets of information about Eleanor as I could find. The detective work involved piecing them all together and deciding which sources were the most reliable, especially where there was no corroborating information. There are many things that eluded me - and would elude every other person who wants to find out the truth about Eleanor: what she really looked like, her relationships with her husbands and children, the truth about her rumoured sexual adventures, her reasons for separating from Henry II, her whereabouts and activities during the years in which she merits no mention in the sources, and the true extent of her political powers. The fragments of information we have do not give us a whole picture, so I have had to infer my conclusions from what is available. I realise that some people may not agree with them.

How difficult is it to reconcile primary sources that put forward diametrically opposed portraits of Eleanor's character? Were there certain of her contemporaries you tended to trust more, and on what did you base this trust?

This leads on from my previous answer. If there is no corroborative evidence that lends credence to a source, I have tended to trust those who were near to events and therefore probably in a position to know, or who knew such people. One must always take into account the prejudices of medieval chroniclers, many of whom were monks who believed that women were of little importance in God's scheme of Creation, and that females who behaved like Eleanor were an abomination!

Eleanor has held a lasting fascination for generations of historians. How do you think portrayals of Eleanor have changed to reflect the concerns of the age in which they were written?

For centuries, portrayals of Eleanor reflected the legends that grew up in her own time and in the century after her death. So powerful were these legends that it was not until the 19th century that historians thought to question them. Before then. Eleanor was seen at best as a shameless adulteress, and at worst as a murderess. In the best medieval tradition, her story was used to ram home a moral lesson, a ploy that was still evident in Agnes Strickland's Lives of the Queens of England (1840-48). Earlier twentieth-century historians found it hard to be objective about Eleanor, and some even drew historical conclusions from the debunked romantic legends. Now we have become obsessed with her sex life, which no doubt reflects the society we live in. Furthermore, we feel obliged to assess Eleanor within the context of fashionable women's issues, which in my opinion is not a legitimate approach when dealing with historical subjects. And we waste endless rivers of ink on post-Freudian analysis of her character and relationships, when not enough is known about them; such an approach is almost certainly inappropriate and could result in wild inaccuracies. Which probably leaves you in no doubt as to where I stand on such issues!

What do you consider to be the truth behind Eleanor's extramarital affairs? How have past historians dealt with them? Do you think her frank sexuality makes her more appealing to a modern readership?

We do not know the truth about Eleanor's so-called extra-marital affairs, and we probably never will. The conclusions I reached in my book were based on inferences from contemporary sources. Most other late-twentieth-century historians have drawn other conclusions, that such allegations were fabricated by scandal-mongering chroniclers who were biased against Eleanor anyway. In my opinion, this is to take an exaggerated romantic view of the subject, and I do not think we should ignore what contemporaries were implying.

Setting aside your historian's cap and thinking like a mother, how do you rate Eleanor's maternal instinct? Did you ever find yourself becoming frustrated by her? Or applauding her behaviour?

We know very little about Eleanor's maternal role, but speaking as a mother myself, I would have found it hard to endure the long

separations from my children. Nor do I approve of mothers having favourites, as Eleanor certainly did. But who are we, in our age, to judge the actions of those who lived in a very different era, with different priorities?

You've told me that you received an early call to history through the fine historical novel Katherine, by Anya Seton. Do you think well-researched, rigorous historical fiction can be helpful in understanding a person and her period?

I entirely agree that well-researched historical fiction can be an aid to understanding history. In many cases, it was a historical novel that introduced me to historical persons or periods. There are, however, two problems with this. Firstly, there is very little of this kind of fiction about nowadays; I was told recently it was a very unfashionable genre when I tried to publish a novel about Lady Jane Grey. Secondly, when it was fashionable (in the 60s and 70s), the genre became debased by a flood of run-of-the-mill books. There are very few historical novels of the calibre of Anya Seton's Katherine.

What's next? Will you work your way through the Plantagenets?

I am due to publish Henry VIII: King and Court in June 2001, and am now researching another historical whodunnit, Mary, Queen of Scots and the Murder of Lord Darnley. Future titles are now under discussion, but I am keen to write another medieval book, possibly on John of Gaunt or Isabella of France - or perhaps a book about the Tower of London. I have submitted about a dozen ideas to my agent, and I'm bursting to write them all!

U.S. INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, 2000

Why did you choose to write about Eleanor of Aquitaine?

I have always been interested in the role of women in history, particularly in the medieval and Tudor periods, and also fascinated by royalty. Therefore writing the biography of a mediaeval queen held a special appeal for me. This project actually started life around 1975 as part of a much grander project. I had just finished researching and writing a book that would later be published as The Six Wives of Henry VIII, and, having greatly enjoyed writing about these Tudor queens, it was a natural progression for me to want to research their predecessors, the Norman and Plantagenet queens. This was a much more challenging enterprise, given the relative paucity of contemporary sources and the barrier created by centuries of incredulous and romantic supposition, and also considering the sheer scale of the research: the lives of twenty-one women over five centuries (1066-1503). Nevertheless, I completed that research during the 1970s. It was a wonderful project, and when I look at it now I still get itchy fingers! Sadly, the vast collective biography that I planned was never written. Some of the research was used for other works such as The Wars of the Roses and The Princes in the Tower, and for another unpublished work, The Last Plantagenets.

Over the years, several readers had written to suggest that I write a book about Eleanor of Aquitaine, and this prompted me to look again at the great mass of research notes about her that I had accumulated all those years ago. Around 1991, convinced that there was enough material to write a fascinating story, I suggested a biography of Eleanor to my agent, who approached my British publishers about it. My then editor was against the idea, feeling that it would not be possible to write a biography of a woman eight centuries dead that was on a par with a richly sourced work on Henry VIII's wives. Over the next few years I proposed the book several more times, but it was only after I had written my biography of Elizabeth I that it was felt that the time was right for me to publish a book on Eleanor. The research needed to be updated, but it was a thrilling feeling to see this cherished project come to fruition after nearly a quarter of a century.

What was so remarkable about Eleanor of Aquitaine?

Her famous beauty and the notorious scandals that attached to her name would have attracted attention in any age, but Eleanor was one of the most sought-after heiresses of the Middle Ages, and twice a queen. Her unusual longevity afforded her more scope to astonish, impress and shock her contemporaries; moreover, she seemed to delight in defying the conventions of her time. Such was her reputation that fantastic legends about her evolved after her death, and were embroidered during the succeeding centuries. I very much enjoyed the challenge of stripping away these legends and the contemporary prejudices of the monastic chroniclers in order to discover the real woman beneath.

How did you go about researching her life?

I was very fortunate in that, during the 1970s I lived in Norwich, Norfolk, where they had the most wonderful reference library, which sadly later burned down. Norwich Library had most of the Rolls Series of medieval chronicles, which were edited and translated during Queen Victoria's reign under the auspices of the Master of the Rolls. These chronicles, and of course many other works, formed the basis of my research on the medieval queens, and I transcribed every entry I could find on them. I also read modern works to see how later writers viewed Eleanor. My conclusions, however, were my own. The chronicles for the later part of the twelfth century are some of the best that survive from the medieval period, yet despite being relatively objective, most were in some way biased, and nearly all reflected the medieval prejudice against women. No contemporary biography of Eleanor exists, so this project was basically a piece of detective work, weaving together a myriad number of small fragments of information into a cohesive whole. Even then, there are periods of time for which no reference to Eleanor survives. Where this occurs, I have been very careful to avoid making sweeping asumptions about her movements that cannot be, at least in part, substantiated by contemporary evidence.

What did you learn from her life? What can others expect to learn?

The most important lesson we can learn from Eleanor's career is that impulsive, self-indulgent behaviour rarely leads to true happiness. Eleanor's interference in politics while married to Louis of France only led to her being sidelined by more powerful forces at court. Her probable affairs and intrigues with other men led to an estrangement from her husband. Her insistence on accompanying him on crusade resulted in months of hardship and privation, and political and personal disaster. Her defiance of Henry II was punished by sixteen years of confinement.

On the other hand, a strong and positive lesson that comes from Eleanor's story is that age and hardship bring with them the kind of wisdom and patience that are in themselves a form of greatness. Eleanor, having learned these virtues the hard way, emerged from confinement at the age of 67 and ruled England wisely and well. In an age that is obsessed with youth and despises any form of ageing, we should do well to learn from Eleanor's example that it is possible to be a high achiever even after the age at which most people have retired from work. Her example teaches us to celebrate the wisdom and ability of older people, and to aim for an active and fulfilling life for as long as we are able.

Why should people want to read about Eleanor? Why read history anyway?

Having been fascinated by Eleanor for many years, I find it hard to understand why people should not want to read about her! However, I would say to the sceptics that hers is a story with strong elements of power, intrigue, spectacle, adventure, violence and sexuality - all riveting aspects of the human condition, and the stuff of which many best-sellers are made.

Why people read history at all is a much wider question. History is basically about people, people like ourselves, and we are intrigued as to how human beings cope in different circumstances and in different ages and societies. Hence the popularity of social history. We also read history simply because we want to know what happened in the past, and in some cases, wish to benefit from it, for by studying the past, we can avoid making the same mistakes in the future, or even make predictions for the future.

People also read historical works if they feel the books have something new to say about a specific subject, as a result of new research or a new interpretation of the facts. People like me read history books for research purposes, because we are like detectives, thirsty for even the tiniest fact that will throw light upon the truth. Personally, I view history books, non-fiction or fiction, as a form of escapism. If I am stressed or depressed, a couple of hours spent in another century will leave me feeling refreshed and restore my equilibrium. I suppose people read fantasy or science fiction books for the same reason. And like them, perhaps, I often feel that the past was, in many ways, a better world than we have now. So I must conclude that, for people like me, a love of history is a form of nostalgia.

What did you think of Katharine Hepburn's performance in The Lion in Winter?

I thought it was superb. To me, she was Eleanor. I first saw the film when it came out in 1968, I now have it on video, and I have not changed my views, even after having researched Eleanor's life in depth. The quote, spoken by Eleanor to her son John, 'Hush, dear. Mother's fighting.' just about sums up Eleanor to me!

Naturally, dramatic liberties have been taken with the facts. The action takes place over one Christmas in the 1180s, when Eleanor is summoned from prison to join her feuding husband and sons at Chinon for the festival. Afterwards, she is sent back to prison. Such visits did occur, yet we know nothing of the personal interactions that took place within the Angevin family during them. James Goldman has used what is known of the Plantagenets to paint a credible scenario of the tensions between them: the love-hate relationship between Henry and Eleanor, her contempt for, and fear of, his younger mistress, who also happens to be affianced to Henry's son, Richard the Lionheart, who is portrayed as an anguished man coming to terms with his homosexuality. I would take issue as to whether Richard really was a homosexual, yet given the prevailing view of scholars at the time the play was written, this is a legitimate portrayal. Henry and Eleanor's middle son, Geoffrey, is shown as a devious and unscrupulous rogue, which he was, while the youngest son, John, is portrayed as an objectionable, uncouth teenager. The chaotic squalour of Henry's court is a brilliant backdrop to the razor-sharp script, as alliances are formed and broken and Henry and Eleanor alternately bitch at each other or play the devoted couple.

I hear that the film is to be remade this year, with Anthony Hopkins as Henry II (he played Richard in the original film) and Meryl Streep as Eleanor. Generally, I am not in favour of remakes - they rarely live up to the original - but I have no wish to damn this one out of court. Given its impressive cast, it may well be a winner.

If you want to find out what Eleanor was like, watch The Lion in Winter. And read my bookl

FROM LONDONER'S DIARY, THE LONDON EVENING STANDARD, 23 AUGUST 2000

THE KINGMAKER

Leading historian Alison Weir gave a reading from her latest work, a biography entitled Eleanor of Aquitaine, at Waterstones in Piccadilly last night.

'Eleanor was a firebrand,' Weir informed me afterwards. 'She had two husbands, but knew many others — in the biblical sense. She bore ten children, two of whom, Richard the Lion Heart and John, became kings of England, and she lived to the ripe old age of 82 at a time when life expectancy was less than 35. Her own lifetime encapsulated events as momentous as the crusades, the martyrdom of Thomas Becket, and the age of Robin Hood. Renowned throughout Christendom for her beauty, she was a strapping lady. Most of her actual utterances are lost to history, but two brief comments survive, both directed to her first husband, Louis VII of France. "I have married a monk not a king!" she reportedly exclaimed. "You are not worth a rotten pear."'

FROM THE WINDSOR, SLOUGH AND ETON EXPRESS, 31 AUGUST 2000.

Many women have exerted a fascination that has transcended the centuries. But not many have lived lives intriguing enough to warrant a biography 800 years after their death. Eleanor of Aquitaine's life would be envied by a soap-opera star. She was queen of France until the King divorced her, and went on to become queen of England and mother of Richard the Lionheart and King John, backing three of her unruly sons when they declared war on their father, her husband. She was locked up for years as a result, re-emerging at a fabulous age to become virtual ruler of England.

But despite Eleanor's amazing story Alison Weir, author of new biography Eleanor of Aquitaine by the Wrath of God, Queen of England, says it took her eight years to persuade her publishers that the book was a good idea. Alison, who visited Methvens Booksellers in Peascod Street, Windsor, last week to promote her book, says: 'They did not see how it was possible for anyone to write an interesting biography about someone who had lived so long ago. I suppose they didn't see how I could possibly get hold of enough information to bring her to life.'

In fact Alison was probably the one woman equipped to do this. She had already published best selling books about Henry VIII, the Princes in the Tower, Elizabeth I and the Wars of the Roses. She says: 'It all began in 1965 when I read a book about Henry Vlll's first wife, Katherine of Aragon. It wasn't very good but it inspired me to find out more. I spent years in libraries finding out all I could about the kings and queens of history. I did enough research to fill several books years before I was ever published, but it was strictly a hobby back then.'

Alison finally got her first book accepted in 1987. Before that she had worked as a civil servant and managed a school for children with learning difficulties. She says: 'My own son has learning difficulties so I ended up running a school in Carshalton to cater for others like him. It got pretty hectic when the council started sending children to us. When John was allocated a place at a special school to take his GCSEs, I became a full-time writer.'

It was then that Alison began to put all those years of research to good use, and now she is known and respected as one of our premier historical biographers. Critical reaction to her book about Eleanor has been amazing. The Literary Review said: 'Her biography reads like a medieval romance, a marvellous intermingling of fact with legend.'

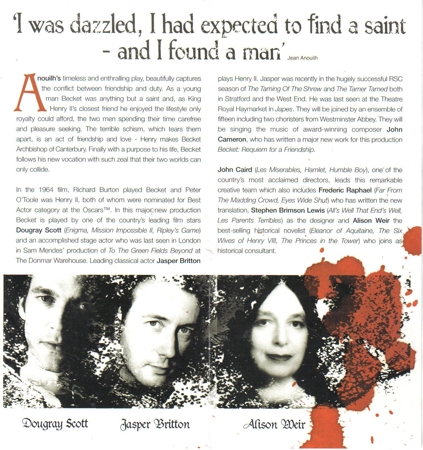

IN 2004, I WAS THE HISTORICAL CONSULTANT FOR THE WEST END PRODUCTION OF JEAN ANOUILH'S PLAY, 'BECKET'.

Press article:

DOUGRAY SCOTT is filming in New Zealand but he has taken his homework with him - biographies and textbooks about the complex relationship between Henry II and Thomas Becket. The actor will portray Becket - once the monarch's closest friend and political ally - in a new adaptation by Frederic Raphael of Jean Anouilh's play, Becket. Dougray is in New Zealand shooting a drama called Perfect Creature, with Saffron Burrows. When he returns to our shores he will go into rehearsal with Jasper Britton, who will portray Henrv II, and award-winning director John Caird, who will stage the searing tale of friendship and betrayal at the Theatre Royal, Haymarket. Producer Kim Poster has contracted Alison Weir, an authority on medieval history, to be the production's historical consultant. It was through Ms Weir's biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine, Henry's wife, that Ms Poster became interested in the play. 'It's a moment of British history that fascinates me,' she told me. 'When Anouilh started to research the play, he realised that Becket wasn't a saint, he was a man. So I thought the idea of having an extraordinarily sexy and charismatic Becket would be doing justice to Anouilh's original intentions.'

Henry and Becket had been close - they drank and wenched together - but when the king made Becket archbishop of Canterbury in the hope of some co-operation, his old friend took his religious duties surprisingly seriously, which angered the monarch.

Caird's production will include two choirboys from Westminister Abbey who will sing songs written by John Cameron.

Becket begins previews at the Theatre Royal on October 20 and has its official first night on October 27. Readers may remember Peter O'Toole and Richard Burton (as Becket) in the 1963 movie version.

FROM THE TELEGRAPH ARTS SECTION, 16 OCTOBER 2004:

"Anouilh's nameless 'young Queen' was Eleanor of Aquitaine, a proud and powerful heiress. She was a decade older than Henry, whom she married after ridding herself of the unattractive King Louis of France. As Alison Weir shows in her excellent biography, the Queen and Henry were, in their early years at least, passionate lovers in a royal world of arranged and loveless marriages.'

At the time I was working as the historical adviser for Becket, I was asked to development a treatment for a play about Eleanor of Aquitaine. It was never finished, due to pressure of work, but you can read it here:

ELEANOR THE QUEEN

A play by Alison Weir

ACT ONE

Scene 1: Fontevrault Abbey, 1202

Scenery: Three gothic arches in white brick. Two tombs with effigies - Henry II and Richard I - at either side of the high altar, on which stands a crucifix.

Music: (very softly) Plainchant by female voices

Eleanor, 80, is to be received as a novice. She is making her confession, and we hear this only as a recorded voice.

This is the backdrop to the play, as Eleanor's comments will be heard from time to time, as if she was speaking to her confessor.

The BISHOP is standing, splendidly robed, before the altar. ELEANOR, wearing a plain habit, is escorted by the ABBESS and FOUR NUNS, before him, and prostrates herself on the pavement, arms outstretched. The NUNS stand, two by two, either side of her, with their backs to the audience. One is carrying a folded black habit, veil and crucifix. The BISHOP raises his hand in benediction. The music swells to a crescendo, then dies down to silence.

ELEANOR'S VOICE: I wish to make confession. Father, before I take the veil in the morning.(speaks of her intention and reflects generally on her life, without giving too much away, but hinting at great turbulence and tragedies.) But I was a great heiress, thegreatest in all Christendom. My lands stretched down from the Loire to the Pyreneees, and across from the sea to Massif Centrale. But my dowry was not just the rich lands of Poitou and Aquitaine. I was fifteen and m beautiful. The minstrels sang that I was without peer...

The first NUN on the left turns slowly to face the audience, pushes back her veil and wimple, discards her habit and raises her head slowly to reveal the young ELEANOR, clad in a simple but elegant white gown and a circlet of bejewelled flowers crowning her long hair. She is bathed in a spotlight as the scene darkens and the stage is cleared. The scenery swivels round to show brilliant white arches adorned with climbing roses. We are in a garden in southern France, and it is a sunny day.

Scene 2: Bordeaux, 1137

Enter DUKE WILLIAM OF AQUITAINE from right. He greets his daughter warmly. He explains that he is going on pilgrimage to the Holy Land and that he is leaving Eleanor under the protection of the King of France and in the care of Dangerosa. This scene should convey much about Aquitaine and about Eleanor's youth. After DUKE WILLIAM has left, Eleanor strums her cittern and plays a troubadour song, as her three DAMSELS (the NUNS of the previous scene) dance gaily around the garden, playing beribboned tambourines. DANGEROSA looks in on them benevolently.

Enter a MESSENGER (previously the BISHOP), who takes DANGEROSA aside and confers urgently with her. She claps her hand to her mouth and announces that DUKE WILLIAM has died. ELEANOR is grief-stricken. Her grief is not greatly allayed when the MESSENGER returns to announce that the King of France, having heard the tragic news, is sending his son to marry ELEANOR. Some discussion with DANGEROSA follows, then ALL PLAYERS exit as a mighty chord from a cathedral organ rings out as the roses are removed from the backdrop and the altar is moved to centre stage. The BISHOP processes to it.

ELEANOR, wearing a chaplet of flowers, enters from the left, followed by her three DAMSELS and DANGEROSA. At the same time, LOUIS OF FRANCE, a timid boy of 16, enters from the right, followed by three KNIGHTS. ELEANOR and LOUIS kneel facing each other before the BISHOP, who raises his hand in blessing. The Te Deum Laudimus swells as the marriage ceremony is acted out in mime. At the end, ELEANOR and LOUIS stand with their hands joined and walk towards the audience as if they were emerging from the cathedral. The DAMSELS and KNIGHTS follow, then DANGEROSA, then the BISHOP.

One of the KNIGHTS cries: Long life and health to the high and mighty Lord Louis and Lady Eleanor, Prince and Princess of France, Duke and Duchess of Aquitaine, Count and Countess of Poitou, Saintonge and Agen.

As he is speaking, the lights dim and ALL PLAYERS EXCEPT ELEANOR AND LOUIS exit to left and right, in formal procession. ELEANOR and LOUIS remain standing, hand in hand, as a great tester bed with a rich counterpane is wheeled to centre stage by the DAMSELS and KNIGHTS, who also place lighted candles on free-standing tall iron sconces either side of the bed. They are the only lighting during this scene.

The DAMSELS take ELEANOR to the left of the stage, disrobe her and help her into bed, where she sits upright. At the same time, the KNIGHTS take LOUIS to the right and do the same. Then the BISHOP enters from the right and blesses the bed.

Enter DANGEROSA from left. She provides suitably bawdy encouragement

The BISHOP exits, followed by DANGEROSA (who blows out the candle on Eleanor's side), the DAMSELS and the KNIGHTS, all giggling and guffawing, carrying the discarded clothing. ELEANOR and LOUIS sit silently. In the background can be heard the far-off playing of a harp. Then LOUIS gets out of bed and falls to his knees beside it, praying. ELEANOR looks nonplussed, and after a time she lies down. Louis is still saying his prayers. Then he rises, blows out his candle, gets into bed and settles down to sleep.

After a few moments, there is an urgent banging on the door, heard offstage. LOUIS and ELEANOR sit up, clutching the bedclothes around themselves.

LOUIS: Enter!

Enter the MESSENGER, who has come to tell LOUIS of his father's death. He and Eleanor are now King and Queen of France. The scene ends with ELEANOR comforting LOUIS in his grief and his turning to her for comfort. As the lights dim, the audience is left with the impression that the marriage is about to be consummated after all.

Scene 3: Paris, 1142

A new backdrop of three gothic stone arches, the two outer with brilliant stained glass, lit from behind, and in the centre a pointed archway.

ELEANOR is seated with her three DAMSELS and her mother-in-law, QUEEN ADELAIDE; they are embroidering a tapestry. ELEANOR wears a rich, low-cut robe and a bejewelled circlet atop her loose hair. A discussion follows that reveals much about Eleanor's life in Paris. The tension between Eleanor and Adelaide is palpable. As they are talking, a procession of three MONKS enters from right, chanting, crosses the stage and exits left. LOUIS follows humbly behind them. He ignores the women for he is lost in prayer.

The conversation resumes, and turns to the scandalous affair between Eleanor's sister, Petronilla, and Raoul, Count of Vermandois. ADELAIDE is very disapproving. ELEANOR sticks up for her sister, and it becomes clear that the scandal has resulted in an armed conflict. As they speak, a spotlight reveals PETRONILLA and RAOUL kissing passionately in the archway behind.

Enter LOUIS, very distraught.

He tells, in graphic detail, of the dreadful massacre at Vitry, for which he says he will never forgive himself. At the news, PETRONILLA and RAOUL break apart, shocked, but are unable to resist falling back into each other's arms, and they remain kissing for the rest of the scene, seemingly oblivious to the furore their love has caused.

ADELAIDE blames Eleanor and Petronilla, and when a MESSENGER enters with news that the Pope has granted RAOUL a divorce so that the guilty pair may marry, she castigates LOUIS soundly, asserting that this union will be made in blood. ELEANOR flounces off left, followed by her damsels, as LOUIS sobs on his mother's shoulder. The lights go down and they exit.

Scene 4: Paris, 1142

The same backdrop, but the tester bed is now centre stage, with the candles either side. ELEANOR is lying back on the heaped pillows, as LOUIS kneels by the bed in agonised prayer.

LOUIS: (repeats over and over again) Mea culpa, mea maxima culpa!

Eleanor is tired of Louis' conscience and his distress. She is clearly a very frustrated woman, and the row that takes place in this scene, reveals much about the couple's sex life, or lack of it, and the effect on Eleanor.

ELEANOR: I have married a monk and not a king!

Eleanor also bemoans the fact that the couple as yet have no children, and no heir to France. Again, she blames Louis. In desperation, she makes an effort to seduce Louis, but love-making is the last thing on his mind. He pulls away, and as she lies there weeping, he is oblivious. Instead, he starts talking about making reparation for the massacre by going on a crusade to free the Holy Land from the Turks, At this, ELEANOR brightens. "Anything would be better than this tedium!" She announces that she will take the Cross too, and go with him. Louis protests, and they argue again. Eleanor wins. Lights down, exit, clear stage.

Scene 5: The plain of Vezelay, Burgundy, 1147

Daylight, blue sky. A huge red crucifix in the Byzantine style hangs centrally above the stage at the back. Below it, stands (St) BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX, clad in a habit of unbleached wool and sandals. He is an ascetic and a zealot, with a profound air of sanctity and authority. Before him kneels LOUIS, bareheaded, clad in chain mail and a white surcoat. He holds his sword upright, like a Crucifix. Behind LOUIS, in a line stretching to the left of the stage, kneel three KNIGHTS, similarly clad and positioned. Beside BERNARD to the right is a MONK holding a basket full of red felt crosses. BERNARD takes one and, uttering the requisite words, ceremoniously attaches it to LOUIS" breast. LOUIS rises, moves to the centre front of the stage and kneels facing the audience in a state of religious ecstasy as the other knights go up one by one to BERNARD, who gives them the Cross too. Each then retires to the left, standing resting on their swords. Throughout this scene, a religious chant can be heard faintly in the background.

As Louis kneels, enter from right ELEANOR and three LADIES, all gorgeously attired as if for a party. They are whispering to each other risque tales about BERNARD. But when the third knight has received the Cross, ELEANOR composes herself and goes over to kneel before BERNARD, who gives her the Cross. She exits right very ceremoniously, as her LADIES receive the Cross after her. They follow her offstage.

BERNARD then preaches a short sermon about the aims of the crusade, but cannot resist a jibe about the attire of Queen and her ladies. He is interrupted by the sound of trumpets as ELEANOR and her LADIES come riding onstage from the right, dressed as warlike Amazons, possibly with one breast bared. BERNARD and LOUIS are shocked as ELEANOR announces her determination to take the field with the men, and all the men present are visibly horrified when TWO SERVANTS enter after the ladies with a baggage cart piled with every luxury a travelling woman could want. But ELEANOR quells LOUIS with a look. Clearly she has got the upper hand and he dare not gainsay her. He takes her by the hand and leads her off right, the LADIES and KNIGHTS following, crying "To Jerusalem!", and BERNARD, the MONK and the SERVANTS pulling the cart) bringing up the rear.

Scene 6: Antioch, 1148

A colonnade of white pillars forms the backdrop. In front is a couch draped in exotic oriental fabrics. Faintly, we can hear a troubadour song. ELEANOR is seated on the couch with her uncle, RAYMOND, PRINCE OF ANTIOCH, a handsome man of 36. She is telling him about a disaster that befell the army on Mount Cadmos, and how everyone has blamed her for it. RAYMOND is sympathetic - overly so, for he clearly finds his niece very alluring, and ELEANOR is playing up to this. Affectedly, she starts weeping, and RAYMOND takes her in his arms to comfort her. The next moment, they are kissing passionately. Between kisses, RAYMOND tells ELEANOR exactly why Louis is mismanaging the crusade, and what he should really be doing. This conversation continues as they wrestle in an urgent embrace, which RAYMOND ends by pulling away. "Let me show you how to couch a lance properly!" He picks up ELEANOR and carries her off left. The unseen troubadour continues to sing in the silence.

Enter LOUIS and THIERRY GALAN, his adviser, who disapproves of Eleanor, who has ridiculed him because he is a eunuch. They discuss the dismal progress of the crusade, then THIERRY, with an extravagant show of reluctance, asks LOUIS if he has heard the rumours about Eleanor. LOUIS clearly does not want to talk about them, but THIERRY persists, and we learn that the Queen's conduct with Raymond is causing a scandal.

As they are talking, ELEANOR enters, adjusting her veil. She is clearly surprised to see Louis and Thierry. She curtseys to LOUIS, while THIERRY rises and bows to her. LOUIS dismisses THIERRY, who exits, smirking. LOUIS then confronts ELEANOR with the rumours. She says she has been spending time with Raymond to discuss strategies for the crusade, but LOUIS will not let her dictate to him, and a blazing row ensues. In the course of this, ELEANOR asks LOUIS to agree to an annulment of their marriage. She has had enough. LOUIS is devastated,for he loves her in his way, but he eventually agrees to divorce her

if the French barons agree. ELEANOR exits, visibly relieved and unmoved by Louis’ distress.

THIERRY returns with some parchments - an excuse to find out what all the shouting was about. LOUIS confides in him about the quarrel, and THIERRY persuades him to take a firm line with ELEANOR. There should be no annulment, and she should forcefully be taught a lesson. LOUIS agrees. For once, he is playing the man. They exit, and the lights dim.

Moonlight shines through the pillars to reveal ELEANOR sleeping on the couch. Suddenly, three KNIGHTS burst in from the left and bundle up ELEANOR in her counterpane. In response to her protests, they tell her that the army is leaving Antioch by night and that she is going with it. From now on, she will be Louis’ prisoner. They then carry her offstage, struggling and protesting. Lights down.

Scene 7: The Vatican, 1148

A backdrop of rich curtains hangs by rings from a pole. (Behind the curtains [unseen as yet], against a backdrop of cloth of gold, is a richly-hung bed.) A raised papal throne is halfway to the left, and a prie-Dieu halfway to the right.

The POPE, attended by his clerk, JOHN OF SALISBURY, enters. They are discussing the failure of the crusade and the coming audience with LOUIS and ELEANOR. It is now well known that the couple are estranged. In the interests of France and the succession, the POPE is resolved to bring about a reconciliation.

Enter LOUIS and ELEANOR. They kneel in turn before the enthroned POPE and kiss his extended toe. He then commiserates with them over their failed crusade, and they tell him something of their adventures since leaving the Holy Land. ELEANOR reveals that her ship got blown off course in the Mediterranean and was captured by Barbary pirates, who took it to the coast of Africa, whence the crew managed to escape. LOUIS says he was very relieved when the couple were reunited in Italy. The POPE takes this as his cue to point out that LOUIS must love ELEANOR very greatly, and he is relieved to find out that rumour

has lied about their marriage. LOUIS seizes the opportunity to reveal his grievances with ELEANOR, and she retaliates in kind. The POPE insists that they heal the rift. Drawing back the curtains, he shows them the bed he has prepared for them and insists that they use it to good use. He makes them kneel either side of the bed, blesses it, then they get into it and he pulls the curtains together. He then kneels at the prie-Dieu and prays for God's blessing on the union and an heir to France. Lights down.

Scene 8: Paris, 1151

The backdrop is the gothic arches again. Two thrones stand before it; one is occupied by LOUIS. BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX stands next to LOUIS. LOUIS and BERNARD are discussing the ambitions of Louis’ vassals, Geoffrey, Count of Anjou and his son, Henry, who are coming to court so that Henry can pay homage to Louis for Normandy, which his father has ceded to him. BERNARD thoroughly disapproves of them both, asserting that they are descended from the Devil. LOUIS is more concerned about the threat posed by Henry's prospects of uniting Anjou, Normandy and England under his rule.

BERNARD raises the question of LOUIS' marriage. The King and Queen still have no son, only two daughters. Eleanor has been clamouring for an annulment. BERNARD has doubts about the legality of f the marriage; he also clearly thinks that Eleanor is a bad influence on Louis. BERNARD urges LOUIS to think again, and LOUIS is half-persuaded. At this point, ELEANOR enters, followed by her THREE DAMSELS. As she seats herself on her throne and the DAMSELS stand to the side of it, ELEANOR tells LOUIS that Count Geoffrey and his son have arrived at the palace. BERNARD tells ELEANOR that he has spoken with LOUIS about her request for an annulment, but LOUIS interrupts and says he is thinking about it. ELEANOR registers intense irritation.

A trumpet sounds the arrival of GEOFFREY, COUNT OF ANJOU, a handsome man of 38, and his son, HENRY, a stocky, energetic and virile youth of 18. They bow to LOUIS and he welcomes them, saying he is happy that past differences have been resolved and that good relations are to be restored. GEOFFREY then kneels to kiss ELEANOR'S hand. She stares straight ahead, her face set. He looks directly at her face,long and hard, but she will not respond. After this pregnant pause, GEOFFREY rises and his place is taken by HENRY. As HENRY kneels and takes ELEANOR'S hand, their eyes meet and the effect is electrifying.

ELEANOR'S VOICE describes the pure lust she felt at that moment, and how she knew it was reciprocated. As she speaks, LOUIS is turned away from her, murmuring an aside to BERNARD, while the perceptive BERNARD is watching ELEANOR disapprovingly.

HENRY visibly forces himself to leave ELEANOR, then kneels before LOUIS to pay homage, after which LOUIS gives both GEOFFREY and HENRY the kiss of peace. Lights down on this tableau.

Scene 9: Paris, 1151

The same backdrop, but the royal bed is now centre stage. Only one candle lights the scene. ELEANOR and HENRY, their clothes disarrayed, are tumbling in the bed in a breathless, passionate embrace. ELEANOR tries to fend him off, protesting that he should not be there and that they are running a terrible risk, but he pinions her down and tells her to order him to leave. She cannot bring herself to do so, and, having established that Louis never visits her at night, he triumphantly resumes their love-making. Presently, they reach a shattering climax.

As they lie together afterwards, ELEANOR reminds HENRY that she is eleven years his senior. He says he doesn't care. She then, very provocatively, says she feels she should tell him that she slept with his father five years before. He says he knew that, and jokes about the affair putting them between the forbidden degrees of consanguinity.

HENRY: But we needn't shock the Pope. We can always plead our joint descent from Duke Robert of Normandy.

ELEANOR: But why should we trouble the Pope about it?

HENRY: When we apply for a dispensation for our marriage. Because, my lovely Eleanor, I intend to have you for my wife.

ALISON WEIR ON HISTORICAL DRAMAS

Is there any point in dramatised history being historically accurate? I asked myself last year when, frustrated with the production's cavalier attitude to history, I resigned as consultant on the TV series of Henry VIII and his wives, starring Ray Winstone. Latterly, I have had a much happier experience working on Jean Anouilh's ‘Becket’, about to open in the West End. But the question remains: why are audiences being sold short by what passes as historical drama these days?

This is a subject on which, as an historian whose life is spent verifying every last detail, I have strong views. And as an historian I probably have an unfair advantage, for many lay people would neither know nor care if a character in a historical drama wore a costume that was 30 years out of period, or spoke in anachronisms. I'm the first to admit that one can be too pedantic. But I admit to foaming at the mouth when hearing of a television director who believed it to be 'demeaning' to have to follow the facts of history - a breathtakingly arrogant view, in my opinion.

Film makers do not need to change the facts, for history is already packed with colourful, dramatic stories. Henry VIII had six wives, for goodness sake, and beheaded two of them - isn't that drama enough, without inventing further scenes of gratuitous sex and violence? And no, he wasn't a Tudor version of a lager lout: he was a cultivated man who spoke several languages, read St Thomas Aquinas for pleasure and had exquisite courtly manners. So why are we still seeing variations on the caricature invented by Charles Laughton?

The answer, I suspect, lies in inverted elitism: let's use the kind of actors who will appeal to a younger audience. Because violence and sex sell, let's make the executions more bloody and add the odd rape scene. Even if it never happened. And let's not bother with headgear or formal court dress - tousled hair and open necks look so now.

Not only is this deeply disappointing to the kind of people who are interested in history and know a great deal about it, it also misinforms people who but take film and television as gospel truth. I frequently get comments on 'facts' culled from some historical travesty of a film. Elizabeth can't have been a virgin, we saw her in bed with Dudley. I could go on.

My family refuse to watch historical drama with me because I usually end up muttering grimly all the way through. Yet many films made thirty years ago are excellent: ‘The Lion in Winter’, for example, or ‘A Man For All Seasons’. In these, there is at least an attempt at authenticity, and a dramatic truth despite occasional inaccuracies.

For there are times when dramatic licence is permissible. After all, the chief purpose of drama is to entertain. Anouilh's ‘Becket’ is still powerful even though the protagonist is incorrectly called a Saxon and enjoys a mistress despite his real-life counterpart's vow of chastity. Likewise, we might know that Sir Thomas More burned heretics and used scatological terms against his enemies, but we can still delight in Paul Schofield's portrayal of his as a gentle man.

I have recently ventured into the field of historical fiction writing, in which an author can give rein to flights of fancy wherever the facts are not known. Original sources rarely reveal much about people's inner feelings or their sex lives - plenty of room for invention there! As a historian, I am quite comfortable with that. But I am loath to alter the facts themselves, and I should prefer it if the makers of historical dramas felt the same way. This surely should not be too much of a challenge to the talented people out there. What a contribution that would be, not only to our culture but also to our understanding of history.

Alison Weir on Fair Rosamund

The Oxford Times, 2010

By Chris Koenig

There is a border between the lands of myth and fact which, author and historian Alison Weir told me, you cross 'at your peril'.

She should know. She has now written two books about Eleanor of Aquitaine (1122-1204). The first was a history, Eleanor of Aquitaine, sticking closely to facts and examining all sources rigorously.

Now she has written The Captive Queen, in which she allows myth, legend and conjecture to creep in — though (and this is the important point) always making it clear in notes at the end of the book when that has been allowed to occur.

Eleanor was that remarkable queen, who, 'by reason of her excessive beauty, destroyed or injured nations', according to one contemporary chronicler. She married first Louis VII of France and then Henry II of England (1133-1189). She was the mother of twelve children and co-ruler of a realm stretching from Northumberland to the Pyrenees; but she has been remorselessly vilified by myth and legend over the centuries — not least by allegations that she murdered Rosamund de Clifford at Woodstock.

The author, who will this week talk at Woodstock Town Hall as part of the Woodstock at 900 festival, said: 'I am a popular historian who would have been frowned upon a generation or two ago.