Books

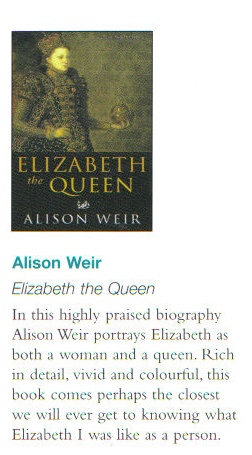

Elizabeth the Queen/The Life of Elizabeth I (1998)

OVER 212,600 copies sold in the U.S.A. alone.

"Weir's book is a scholarly one... An excellent account of the greatest of England`s remarkably great queens." (Kathryn Hughes, The Daily Telegraph)

"Weir is excellent on the complex relationship between Elizabeth and her court of suitors... One of Weir's many merits is to let her subjects mature... An elegant, shrewd and wonderfully vivacious book." (Miranda Seymour, The Sunday Times)

"This often eloquent biography... Her story is of absorbing interest... Alison Weir quotes the words of William Camden that 'no oblivion shall ever bury the glory of [Elizabeth's] name'. We may add this informative and entertaining biography to that eternal record." (Peter Ackroyd, The Times)

"A well-written, sensible book... Weir retells it with a certain panache." (Diarmid MacCulloch, The Independent)

"Weir's detailed account creates such a good psychological portrait of the Virgin Queen... presented in an exciting yet moving way." (The Sunday Times)

"Possibly the closest we shall come to discovering what Elizabeth was really like." (Bolton Evening News)

"The story is intricate and absorbing, the style shrewd and observant... She is particularly good on Elizabeth's private life.This is popular history at its best, richly informative, well-paced narrative, coupled with an eye for the telling detail and emblematic event." (The Yorkshire Post)

"Weir`s riveting narrative is assisted by the language of the era and the Elizabethan love of intrigue." (The Independent on Sunday)

"This absorbing biography brings to life a woman more interesting than all the lords in her kingdom put together." (The Guardian)

"Alison Weir comes closer than any historian before to telling us what Elizabeth was like as a person." (Belfast Newsletter)

"This biography is by an accomplished expert on the period... It is full, fair and judicious, and particularly good on Elizabeth`s private life. I enjoyed it, and I think many other readers will too." (Paul Johnson, The Literary Review)

"This volume represents the culmination of years of research by Weir. Here she brings her characteristic exhaustive attention to detail, an experienced sense of narrative pace and style, and a passion for her subject... A riveting portrait of the Queen." (Kirkus Reviews)

"An almost affectionate portrait... Weir brings considerable zest to her portrait of the Virgin Queen." (Publishers Weekly)

"Alison Weir`s gripping biography... reads with pace." (The Tablet)

"[A] fascinating piece of literary research." (Ms London)

"Alison Weir continues to chronicle the lives of the Tudors with panache... As exciting as any fictional thriller you may read this year." (Royal Leamington Spa Observer)

"The intimate world of the Elizabethan court and of its matriarch is recreated in rich detail, and the spirit of the age evoked with a novelist`s flair." (The Good Book Guide)

"An extraordinary piece of historical scholarship." (The Cleveland Plain Dealer)

"A richly detailed account... brings Elizabeth`s personality to life." (Indianapolis Star)

"A brilliantly researched work of scholarship." (Berkeley Express)

"This biography reads like a novel... Highly recommended." (Douglas County News, Denver)

"A brilliantly researched work of scholarship." (Berkely CA Express)

"Thoroughly researched and thoroughly readable, it is hard to imagine that there is anything worth reading about Elizabeth I that is not in this book." (Coventry Evening Telegraph)

"Alison Weir tells the story of Elizabeth I with panache. There is no interrupting the pace of Elizabeth's story." (Suite 101)

"Alison Weir's book is remarkable. She brings the Elizabethan age and its namesake to vivid life. The research is solid, the writing excellent, the conclusions logical. Ms. Weir brings Elizabeth into the hearts of her readers." (Decatur AL Daily)

"Impeccably, Weir charts the life and times of this astonishing woman. Read this book, especially if you've seen the recent movie." (Metro)

"A very readable, accessible account of a phenomenal woman." (West Lancashire Evening Gazette)

"Her story is told with such readability and style." (Oxford Mail)

"Alison Weir's Elizabeth the Queen stands out firstly by virtue of its sheer, highly informed readability. Weir is perhaps best of all on the living, breathing detail." (Sarah Gristwood, B.B.C. History Magazine)

"Fantastic and fascinating! Rich in detail, vivid and colourful, this book comes as close as we shall ever get to knowing what Elizabeth I was like as a person." (The Bookfiend's Kingdom)

Preliminary U.K. jacket designs.

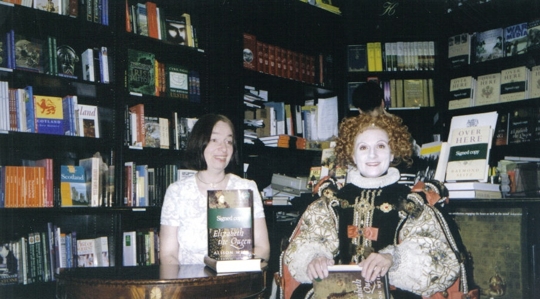

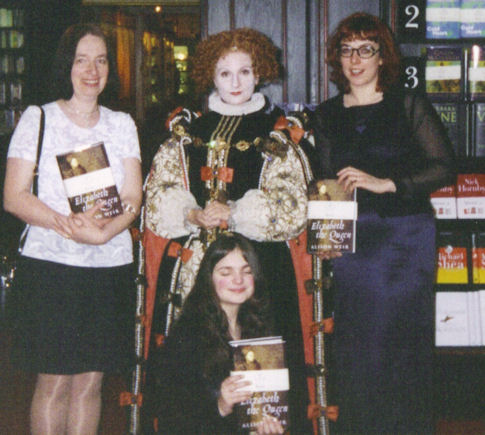

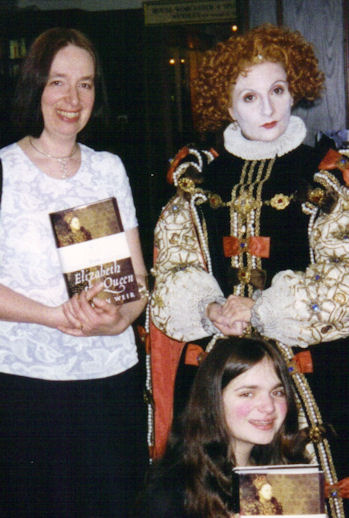

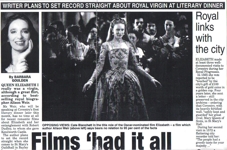

Publication day, 1998: Signing at Hatchards, Piccadilly (above) and Harrods (below), accompanied by a very convincing escort! Our taxi driver was especially impressed! The young lady kneeling at the front is my daughter, Kate.

Above: Promoting an author talk in Canterbury.

Book signing at W.H. Smith at Victoria Station, London

Below: I opened the new branch of Waterstones in Hereford, and Queen Elizabeth (actress Paula Danholm) came too!

ORIGINAL PROPOSAL FOR THE BOOK (1996):

THE PRIVATE LIFE OF QUEEN ELIZABETH I

In recent years there have been several excellent biographies of Queen Elizabeth I, notably Anne Somerset's in 1991, but we would have to go back to Elizabeth Jenkins' superb "Elizabeth the Great", published in the 1950s, for a book devoted to that monarch's private life. Times have moved on since then, and a reappraisal is now appropriate.

In "The Six Wives of Henry VIII" and its sequel, "Children of England", I wrote about the private lives of the earlier Tudor sovereigns, ending - on a cliffhanger - with the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558. While I was working on "Children of England", I touched on Elizabethan sources and thought about writing a future book about Elizabeth's affair with Robert Dudley (later Earl of Leicester) and the mysterious - and timely - death of his wife, Amy Robsart. Preliminary research showed that this was a subject that had not been written about in depth for forty years, and that it might be worth delving into the mystery, treating the evidence strictly chronoligically, as I had done with the sources for "The Princes in the Tower". Yet there was more to this tale than the death of Amy Robsart, for Elizabeth's relationship with Dudley was to last for more than a quarter of a century after it.

I then conceived the idea of continuing my series of books on the Tudor period with a broader work on the personal history and character of Queen Elizabeth I, which would include accounts of her many relationships - both personal and political - with the men who wanted to marry her, notably Leicester, her numerous official suitors, among them Philip of Spain, and - much later - Leicester's stepson, the Earl of Essex. The book would also focus on the Queen's dynamic personality, and give fascinating details about her daily life.

Another theme - one hardly touched upon by other writers - would be Elizabeth's relations with the family of her mother, Anne Boleyn. The Queen was close to these kinsfolk, who in turn proved loyal and supportive. Elizabeth's relations with her royal relations, particularly Lady Katherine Grey, Mary, Queen of Scots, the Countess of Lennox and Arbella Stuart, were of necessity of a more political nature, yet her feelings for her Boleyn kin, who were not competitors for her crown, were based on by family ties. The subject of the personal family relationships of Elizabeth I has long been neglected and a study of it would undoubtedly provide a new insight into the Queen's complex character.

Given the vast amount of source material, such a book would be quite an undertaking, but there is no reason why the subject could not be successfully dealt with in one volume, with all the separate themes being interwoven into one cohesive whole, with the strong figure of the Queen providing a central focus. The title, "The Private Life of Queen Elizabeth I", defines the scope of the work, and makes it clear that it is not a history of the reign, but of Elizabeth's personal life. Nor will it be an account of Elizabeth's life before her accession, as I have written of this in detail in two earlier books. However, her early years will be recounted in an introductory chapter for the benefit of those who have not read the earlier books, because these experiences had a tremendous effect on Elizabeth's emotional development.

I do feel that a book with a strong central character, such as Queen Elizabeth was, would be of interest to many people. Although it is not my intention to write from a feminist viewpoint - which, in my opinion, would not be a legitimate treatment of a historical subject - I do wish to comment on, and emphasise, that Elizabeth I, who was the first to say she was a "weak and feeble woman", was in fact an extraordinary female in an age in which men were dominant.

In 1558, when Elizabeth I ascended the throne, a female sovereign was still a novelty, for her half-sister, Mary I, had reigned for a mere five years. Tudor England was a patriarchal society, and it was unthinkable that a queen regnant would attempt to rule without a husband to guide and protect her, and - most important of all - to give her heirs to ensure the succession. Yet whom should the Queen marry? Her sister's unpopular and disastrous marriage to Philip II of Spain had proved that it was unwise for a queen to marry a foreign monarch, for his duties would call him abroad and keep him there, and there was a danger of foreigners interfering in the affairs of the realm, or England being treated as a satellite state of another country, or being dragged into a foreign war, as had happened, with terrible consequences, under Mary. Of course, the Queen could always marry an English nobleman, but that was certain to lead to faction fights at court and jealousy amongst the peers.

Elizabeth I solved this problem by never marrying, yet for decades she cleverly kept not only her ministers, but numerous suitors of various nationalities in a fever of suspense and anticipation that she would accept their proposals. Thus she managed to retain the goodwill of foreign powers and at the same time revel in the pleasures of courtship and flirtation. Even after she had passed the age for chiIdbearing, men continued to court her, and she continued to give them cause to hope. It was a strategy that required a genius's sense of timing and a stalwart self-control, and there were moments when her private loneliness and regret about her childless state were publicly revealed.

Historians have long pondered about the vexing question of Queen Elizabeth's attitude to sex and marriage. Did her early experiences - the beheading of her mother, her stepmother, Katherine Howard, and Thomas Seymour, who did his best to seduce her when she was in her early teens - leave her with a mental block against sex and marriage? Did she, as has often been suggested, have some physical deformity or condition that prevented her from consummating a relationship or bearing a child? Was the salacious gossip of her day - which accused her of all kinds of promiscuous behaviour - based on truth, or did Elizabeth really live and die a Virgin Queen? In this book, I should like to collate and examine all the evidence, and hopefully draw a logical conclusion.

There will be five themes in the book: the portrayal of Elizabeth as both a woman and a queen, concentrating on every aspect of her

extraordinary character, of which so much is known that it is possible to identify with her moods and feelings; her involvement with her relatives on both sides; her long affair with Robert Dudley; her relationships, sometimes comical, sometimes poignant, with her numerous other suitors, including that with her later arch-enemy Philip of Spain, who had been attracted to her ever since he first met her at her sister's court and presently wished to marry her; and her curious and bizarre relationship with Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, who was beheaded for conspiring against her in 1601. These events will be dealt with chronologically.

The sources for the Elizabethan period are wonderfully rich in detail, and it is possible to learn a vast amount about Elizabeth's daily life, her clothes, what she ate, what she said, the magnificent palaces she lived in, her courtiers, and the intrigues and plots in which they indulged. The Queen was a remarkable woman for her time, using her forceful personality to manipulate and control the power-hungry men around her, not to mention the dangerous and menacing forces that threatened her throughout most of her forty-five year reign. The age to which she gave her name was one of the most colourful and confident in England's history, and in the pages of this book I hope to bring it vividly to life.

A CONVERSATION WITH ALISON WEIR, August 1998, just prior to the publication of The Private Life of Elizabeth I in the U.S.A.

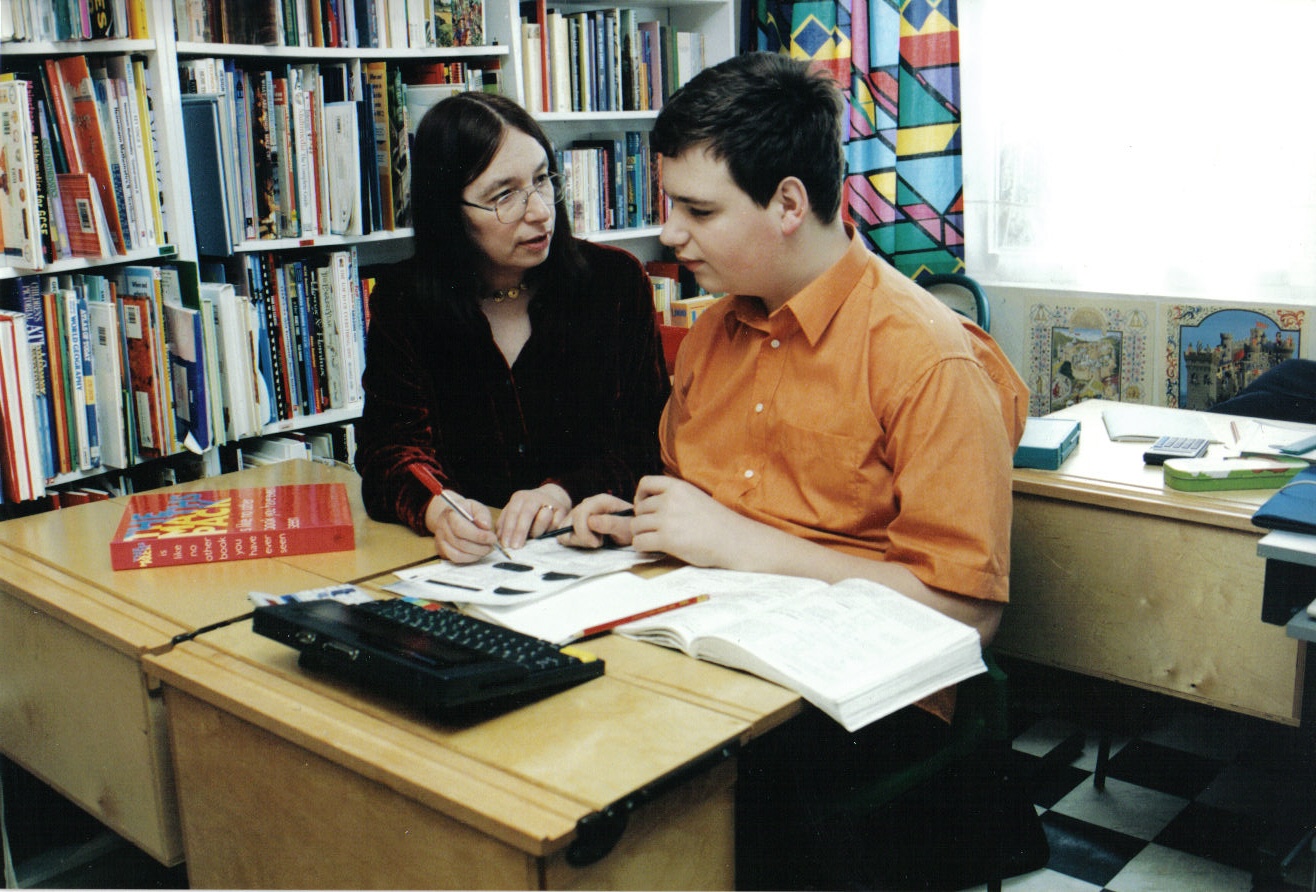

(Above: Teaching my son, John, in 1997.)

When did you first become interested in history?

In 1965, when I was fourteen, I read my first adult novel; it was an historical novel about Katherine of Aragon, and I could not put it down. When I finished it, I had to find out the true facts behind the story and if people really carried on like that in those days. So I began to read proper history books, and found that they did! It was a short step from doing research to writing my own books, and by the age of fifteen I had completed a three-volume compendium of facts on the Tudors as well as a biography of Anne Boleyn, and had begun to compile genealogical information for a dictionary of kings and queens which would, more than two decades later, be the basis of my first published book, Britain's Royal Families.

At school, up to the age of sixteen, I found history boring, for we were studying the Industrial Revolution, which was all about Acts, Trade Unions and the factory system, and I wanted to know about people, because it is people who make history. My teachers were unaware that I was spending all my free periods and lunch-breaks researching my own history projects in the school library. I did pass my G.C.E. exam, but was told that my grade was not good enough to study history at an advanced level. This was a great disappointment as the subject for the advanced course was the Tudors and Stuarts, something about which I already knew a great deal. After leaving school, I passed my History A-Level with honours, on my own steam, after just six months of study. I would love to think that the teachers who excluded me have seen my published work.

When did you begin to write professionally?

During the early 1970s, after attending teacher training college with a view to teaching history, I spent four years researching and writing a book about Henry VIII's vives, but this was rejected by publishers on the grounds that it was too long - something of an understatement, since it filled 1,024 manuscript pages typed on both sides and without double spacing! In 1991 a much revised and edited version of this manuscript was published as my second book, The Six Wives of Henry VIII.

In 1981 I wrote a biography of Jane Seymour, which was rejected by Weidenfeld and Nicholson as being - wait for it - too short. The publishers, however, put me in touch with my present firm of literary agents who, in the course of a conversation about which subject I should choose, rejected my suggestion of a book about Lady Diana Spencer (who became Princess of Wales that year) on the grounds that people would soon lose interest in her! Instead, it was agreed that I should write a biography of Isabella of France, wife of Edward II, but this was never finished because the births, very close together, of my children intervened in 1982 and 1984 and I had very little time for writing.

In 1987, it occurred to me that my dictionary of genealogical details of British royalty - which I had revised eight times over twenty-two years - might be of interest to others, so I rearranged the contents once more, into chronological order. Britain's Royal Families became my first published book, in 1989, for The Bodley Head, and the rest of the story is (dare I say it?)history!

How do you go about writing your books?

I research from contemporary sources as far as possible; fortunately, most of those for the periods I have written about are in print. I use secondary sources to see what views historians take on my subjects, but in the end I make up my own mind, basing my conclusions as far as possible on contemporary evidence. I transcribe my information into chronological order, under date headings, so that when I have finished my research, I have a very rough draft of the book. This method has the curious advantage of highlighting discrepancies and often new interpretations of events, chronological patterns, and unexpected facts emerge. Anyone who has read The Princes in the Tower will know how startlingly well this method of research worked for that particular book.

How would you describe your role as an historian?

I am not a revisionist historian. I do not start with a theory and then try to fit the facts around it. I draw my conclusions from the known facts. As my research progresses, I gain some idea of the viewpoint I will take, but I am always ready to alter it if need be. You have to consider the known facts in detail and avoid supposition in order to get as near to the truth as possible. You must not only take into account what is written about someone or something, but who wrote it, since many sources are biased, prejudiced, or unreliable. Where possible I verify my facts from reliable sources only, and if the only source is suspect, I say so.

Would it be fair to describe Elizabeth I or other powerful women of history as feminists?

As a biographer of several important women, I do not believe that a feminist slant on history is appropriate. You must always judge your subjects in the context of their own age. You may draw parallels, but it is ludicrous to try to portray Eleanor of Aquitaine or Elizabeth I as pioneers of women's rights. They were, indeed, extraordinary women who made their mark in a male-dominated society, but neither made any conscious effort to improve the lot of their sex.

I am fascinated by the role of women in history, and irritated that for so long historians have ignored them as unimportant, a failing I am trying to redress. I am also keen to strip away the credulity of the mediaeval chroniclers and the romanticism of many later female writers. I want my female characters to emerge as real people.

What, then, is your aim in writing history?

I want to bring history and its characters to life by including as much personal detail as possible, by inferring new ideas from the known facts, and by researching the political and social background so thoroughly that my subjects are set in an authentic context. Many people have told me that my books read like novels. That is because I like narrative history. The old adage that truth is stranger than fiction is more than true for me, and if (as a couple of recent reviewers have complained) it is old-fashioned to recount history as a rattling good story - which in many ways it is - then I am happy to be thought outdated.

When you were researching and writing about Elizabeth I, did you come to like her?

Yes, immensely! I was expecting to encounter this formidable, cruel, and rather bitchy woman, but instead I found a highly gifted, compassionate, and witty human being. True, she was imperious, temperamental, and often difficult, but even at these times there is an endearing quality in her. The book is full of anecdotes illustrating her character, and while many are very funny, others are poignant.

There seems to be a trend nowadays towards dismissing Elizabeth's influence over the age that bears her name as negligible. To my mind, that is missing the whole essence of the Queen and her people, and I suspect that many writers propound such theories just to be provocative, or have studied merely the facts without understanding the spirit of the age. You do not have to do very much research to realize that Elizabeth had such a profound influence on England and the imagination of its people that in her own lifetime she was regarded as little less than divine.

What is your opinion of screen portrayals of Elizabeth?

I would say that Glenda Jackson's portrayal for the BBC television series 'Elizabeth R.' (1971) was almost perfect; to me, she was Queen Elizabeth. Despite the small budget for this series, great efforts were made to ensure accuracy - given an acceptable degree of dramatic license - and the standard of acting was superb. Here were no stereotypes, but real people. Older portrayals, including those by Bette Davis and Flora Robson, were more stereotypical and over-romantic. The Queen might have looked authentic, but no one else did!

At least two films are in production now. The British film Elizabeth stars Joseph Fiennes and Cate Blanchett, and is to be released in November. The Daily Mail newspaper has asked me and Dr David Starkey for help with information about the film, because its historical advisor is an unknown and the filmmakers are being very secretive about it. Rumour has it that this is an over-romantic production in which Elizabeth will certainly not be portrayed as the 'Virgin Queen'. I can only say that I hope the producers will have checked their facts, because there is no excuse for blatant inaccuracy in an historical film - look at what they did with 'Braveheart'!

I have heard that Glenn Close is to play Elizabeth in an American film scheduled for release later this year, and would imagine that she would make an excellent Elizabeth. A third film in production, which I read about last year, focuses on Mary, Queen of Scots, but I have heard nothing more about it as yet.

What are you working on now?

I am working on a biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine, a project that is giving me the chance to write at last about the mediaeval period and to flesh out a woman who has been dead for 800 years. It is surprising how much we know about her, and even more surprising how much controversy she provokes even today. I fear I am going to be very provocative in some of my conclusions.

Until last summer, I ran a small private school for children with special educational needs, mainly to meet the needs of my own son, who is dyspraxic. He and the other students have all moved on to senior schools, and I was able to close the school, ending six years of teaching and writing at the same time. I was considering giving up sleep! With more time on my hands, I have been able not only to research Eleanor, but to write a novel about Lady Jane Grey. After I complete Eleanor, I have several ideas for future projects, including the mystery of the Casket letters and whether Mary, Queen of Scots was guilty of the murder of Lord Darnley, a book on Queen Victoria's early life, and The Last Plantagenets, the third volume in the trilogy that began with The Wars of the Roses and The Princes in the Tower. I just wish there were more hours in the day.

Historical Notes: WHY DID ELIZABETH I NEVER MARRY?

by Alison Weir

(The Independent, 9th June 1998)

"I will never marry," the future Elizabeth I declared at the age of eight, and, to the consternation of her subjects, the great Queen kept her word. She even promoted the cult of virginity that was to form the substance of her legend.

For four centuries, historians have speculated as to why Elizabeth never married. In her own day, her decision to remain single was considered absurd and dangerous. A queen needed a husband to make political decisions for her and to organise and lead her military campaigns. More important, she needed male heirs to avoid a civil war between rival claimants after her death.

There was no shortage of suitors for the Queen's hand, both English courtiers and foreign princes, and it was confidently expected for the best part of 30 years that Elizabeth would eventually marry one of them. Indeed, although she insisted that she preferred the single state, she kept these suitors in a state of permanent expectation and even lust. This prevarication was a deliberate policy on the Queen's part, since by keeping foreign princes in hope, sometimes for a decade, she kept them friendly when they might otherwise have made war on her realm.

There were, indeed, sound political reasons for her avoiding marriage. The disastrous union of her sister Mary I to Philip II of Spain had imposed an unwelcome foreign influence upon English politics. The English were generally prejudiced against the Queen taking a foreign husband, particularly a Catholic one. Yet if she married an English peer, jealousy might lead to the formation of dangerous factions at court.

There were other, deeper reasons for Elizabeth's reluctance to marry, chief of which, I believe, was her fear of losing her autonomy as Queen. In the 16th century, a sovereign was regarded as holding supreme dominion over the state, while a husband was deemed to hold supreme dominion over his wife. Elizabeth knew that marriage and motherhood would bring some erosion of her power. "I will have but one mistress here and no master," she told the Earl of Leicester, the man she loved more than any other and to whom she was close for over 30 years.

She once pointed out that marriage seemed too uncertain a state for her. She had seen several unions in her immediate family break down, including that of her own parents. Some writers have argued that Elizabeth was frightened or incapable of the sex act; certainly she had a deep aversion to marriage and feared childbirth. Two of her stepmothers, her grandmother and several acquaintances had died in childbed. Moreover, in pregnancy she was bound to lose her grip on affairs.

Elizabeth's father, Henry VIII, had had her mother, Anne Boleyn, executed for treason and adultery; her stepmother Katherine Howard later suffered the same fate. When Elizabeth was 14 she was almost seduced by Admiral Thomas Seymour, who also went to the block within a year for treason. Witnessing these terrible events at an early age, it has been argued, may have put Elizabeth off marriage.

Elizabeth had to decide her priorities. There was no contraception in those days, and to risk an illicit pregnancy would have jeopardised her already insecure throne. A woman's reputation was paramount, especially that of a queen who bore the title Supreme Governor of the Church of England. Marriage or celibacy were her only choices. Elizabeth was far too intelligent to compromise herself. The choice she made was courageous and revolutionary, and, in the long run, the right one for England.

� From Alison Weir's book Elizabeth the Queen

From the Letters page of the Daily Mail, 15th October 1998

Extract quoting Alison Weir from WHO'S QUEEN! by Peter Whittle, The Culture, 2003

2003 was the 400th anniversary of Elizabeth's death, and also of the union of the crowns of England and Scotland. '"It's a politically sensitive issue," says Alison Weir, one of Elizabeth's most successful biographers, and the author of a new life of her rival, Mary, Queen of Scots. "I think the Scots want to play down the English connection."

Extract quoting Alison Weir from SEX AND THE SINGLE MONARCH by Jane Dickson, Radio Times, January 2006

Alison was commenting on the B.B.C.'s drama, The Virgin Queen, starring Anne-Marie Duff:

The B.B.C. production, with its up-close-and-personal view of sex and the single monarch, helped along by a young sexy cast and a driving 'Tudor rock' soundtrack, presents the Elizabethan court as a hotbed of erotic intrigue. "People don't appreciate," Duff says, "what it was like to be English at that period, how different the national temperament was, how tactile, how fiery ... almost more akin to the Latin temperament of today."

It's a contentious view. Writer and historian Alison Weir, author of Elizabeth the Queen, suggests, rather, that the accession of Elizabeth to the throne produced a 'mini ice age' in Elizabethan court attitudes to sex.

"I wouldn't identify the Elizabethan age as one of great licence," says Weir. "When the Protestant Elizabeth came to the throne, she was, in the eyes of Catholic Europe, a bastard, a heretic and a usurper. So she had to be incredibly careful not just of her own reputation, but the reputation of her court, which was thought to be very staid. The measure of that is that when James I came to the throne, bringing with him a court that really was promiscuous, people looked back on the decorum of the Elizabethan court."

Weir is convinced that, with so much riding on propriety, Elizabeth's virginity is almost certainly a historical fact. Given the lack of privacy in royal life, she argues, it could not have been otherwise. "The Queen would have had servants in her bedchamber and the Yeomen of the Guard keeping watch outside. There were ambassadors from other courts paying the Queen's maids and laundresses to check her linen. If anything untoward had been going on, someone would have known."

Speculation on the Queen's romantic life has always centred on her relationship with Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. "In 1562, when Elizabeth thought she was dying of smallpox," explains Weir, "she referred to the notoriety of her affair with Robert Dudley, and swore to the people standing around the bed that nothing improper had ever taken place. It's difficult for the modern mind to understand, but for somebody on their deathbed in 1562, hell and the whole notion of divine judgement was a very real prospect. So she wasn't likely to make that statement at that time if it wasn't true."

WHY ELIZABETH IS FIRST AGAIN: THE QUEEN WHO STILL RULES US, The Spectator, 17th October 1996

Alison Weir explains what lies behind yet another surge of interest in Elizabeth I

IT CANNOT have escaped many people's notice that there has recently been a significant revival of interest in Queen Elizabeth I. The first signs of this came in the spring, with the reissue of Sir John Neale's definitive biography. Then came my own book, a personal portrait entitled Elizabeth the Queen (Jonathan Cape). Now there is a new film, Elizabeth, which has attracted a great deal of media interest, and an English National Opera revival at the London Coliseum of Donizetti's Mary Stuart, which portrays the interaction between Mary and Elizabeth. Yet to come are two American films, one starring Glenn Close as Elizabeth, the other about Mary, Queen of Scots. Once again, it seems, the Virgin Queen is what publishers call a sexy subject.

She has ever been so. Since she came to the throne in 1558, Elizabeth I has endlessly fascinated the English people and, at various times, historians, novelists, composers, artists, film and television producers, and a world-wide public. Why should Elizabeth, out of England's long procession of kings and queens, exert her charm over us? The answer is complex.

To begin with, people are, in general, fascinated by monarchy. They see a person set apart from themselves, called to live out a very public role in a position of great influence, and attended by awe-inspiring ceremonial and rigid rituals of social deference. The monarch lives in the kind of luxury most of us can only dream of, and their every whim is apparently gratified. He or she is the fount of justice, a priest-like figure who holds the ultimate power of life and death over their subjects.

Yet this does not explain why Elizabeth, of all our monarchs, is so famous and so revered. The Tudors as a family were what is now termed charismatic, larger-than-life characters. Although any¬one related to the much-married Henry VIII is bound to have attracted a wide press, Elizabeth was an extraordinary person.

Born in 1533, she was Henry's daughter by his second wife, Anne Boleyn. Declared illegitimate by Parliament at the time of Anne's execution in 1536, she spent her childhood in awe of her formidable father, the auspices of a succession of sympathetic stepmothers. She benefited enormously from the kind of classical education hitherto afforded only to royal princes, and emerged a cultivated intellectual with a gift for languages.

Abused both emotionally and perhaps sexually by Admiral Thomas Seymour, the husband of her stepmother Katherine Parr, during the reign of her brother Edward VI, she suffered disgrace by association when he went to the block for treason in 1549.

During the reign of her sister, Mary I, Elizabeth was suspected of complicity in a rebellion led by Sir Thomas Wyatt against the Queen and spent three months in the Tower under threat of execution. She was released only when it became clear that nothing could be proved against her. In 1558, she came to the throne on a tide of popular approbation, and would retain the love of her people until her death 45 years later.

What is so outstanding about Elizabeth is not only her intelligence and forceful personality, but her being a great and successful ruler in an age of outstanding achievements: the confident age of the Armada, Drake and Raleigh, Shakespeare, Spenser and Marlowe, and of some of the most able politicians ever to serve an English monarch.

Elizabeth presided over this age and was its inspiration, even if she did not actively influence all its successes. She was also the chief promoter of the English Protestant settlement and a great champion of burgeoning nationalist sentiment.

Throughout her reign, she worked hard to earn and retain the love of her people. 'Be ye well assured I will stand your good Queen,' she told her subjects as she rode to her coronation. To wish neither prosperity nor safety to myself which might not be for our common good. No monarch before or since was ever held in such affection by his or her people, and at the end of her reign Elizabeth was able to say, 'Though God hath raised me high, yet this I account the glory of my crown, that I have reigned with your loves.' This special relationship between the Queen and her people endured beyond her death. It is true that many younger people welcomed the accession of her successor, James I, yet after only a short period of Stu¬art rule the English began looking back to Elizabeth's reign as a golden age, and they would continue to celebrate her Accession Day, observed as a public holiday since around 1571, until the 18th century.

The role she had assumed as the wise and loving mother of her subjects came to be regarded as an ideal one for a queen; in her lifetime, she had deliberately fostered a parallel between herself and the discred¬ited image of the Virgin Mary, filling the void that the banning of such idolatry had left in the spiritual life of the nation.

It was no accident, therefore, that Elizabeth deliberately fostered the cult of the Virgin Queen. Embracing lifelong virginity as a political necessity, she made a virtue of it, and her subjects were encouraged to think of virginity as the ideal state. The poets and playwrights abetted this propaganda, and Elizabeth was able to triumph over what must have been a personal tragedy, and was certainly a risky dynastic decision much deplored by her advisers.

Nevertheless, the Queen succeeded in captivating the imagination of her subjects, and indeed of successive generations: the image of a bejewelled Gloriana in her ever more fantastic state robes, her wing-like collars, huge ruffs and wheel farthingales, with a red wig and eternally youthful face, became imprinted on the national con-sciousness. Today, we are still fascinated by it, yet with our passion for uncovering the most private secrets of our national figures, we are determined to discover the reality that lay behind Elizabeth's carefully contrived public image.

But what most fascinates us today is Elizabeth's role as a woman. Feminists, and indeed many women, see her as an icon because she triumphed as a female ruler, exercising sovereign power brilliantly and effectively in a male-dominated world. She proved she could rule independently without the help of a man and suc-cessfully asserted her autonomy by cleverly fielding all the proposals of marriage made to her. Although the appalling circumstances of her childhood and youth could have made her a victim, she rose above them and made an outstanding success of her life.

She also had to make the choice between career and personal fulfillment that faces many modern women, and we admire her courage and tenacity in the way she faced up to this tough and ultimately heartbreaking decision. Like many women today, she realised she could not have it all.

Furthermore, she is something of an enigma to us. Although the historical evidence overwhelmingly suggests that she was indeed the Virgin Queen she claimed to be, the subject can still provoke furious debate, and much ink has been expended on discussion of the Queen's sexual nature. We live in an age that loves secrets, hidden agendas and revisionist history, and beneath the myths and legends that sur-round Elizabeth we perceive rich pickings to be had, even inventing mysteries when we find none.

Elizabeth's contemporaries would not have been surprised at our obsession with their extraordinary queen. Her first biographer, William Camden, wrote, with great prescience, 'No oblivion shall ever bury the glory of her name, for her happy and renowned memory shall for ever live in the minds of men.'

SHE COULD HAVE BEEN AN ESSEX GIRL, YOU Magazine, 24th May 1998

.. .but Elizabeth I turned down the Earl of Essex, above, as she had all other suitors, including her great love Robert Dudley The Virgin Queen of popular mythology led an often controversial private life, and could even have been involved in a murder, claims historical biographer Alison Weir.

She was one of the most famous flirts in history; men were attracted to her not only because of who she was, but also because of her potent personal charisma. Yet Elizabeth I, Queen of England from 1558 to 1603, was celebrated in her own time, and is remembered today, as the Virgin Queen, an image she consciously promoted.

She was one of the greatest rulers England has ever had, and one of the best loved. She set out to court the goodwill of her subjects, asserting that she was the careful mother of her people. Despite all the vicissitudes of fortune, she retained their love, and at the end of her reign was able to say to Parliament: 'Though God hath raised me high, yet this I account the glory of my crown, that I have reigned with your loves.'

Studying the history of the British monarchy has been my life's work, and I have spent at least ten years researching Elizabeth I and trying to discover what she was really like. The publication of the book that is the result coincides with a huge revival of interest in Elizabeth: there are at least three films about her in the pipeline, notably a major production starring Cate Blanchett and Joseph Fiennes due for release in the autumn.

Many people have in their minds images of Elizabeth of which she would have heartily approved: the royal icon of the Armada years, or the Virgin Queen of the poets who presided over the England of Shakespeare and Raleigh. Yet as my research progressed, a very different human being emerged. Elizabeth was a strong-minded, intelligent, flirtatious and sexy woman with a wickedly mischievous streak. She drove men mad, in every sense.

Elizabeth was the daughter of Henry VIII by Anne Boleyn, who was executed in 1536, having been accused, probably falsely, of plotting the death of the King and committing adultery with five men, one her own brother. Elizabeth was not quite three at the time, and we know nothing of when or how she found out what had happened to her mother. Post-Freudian historians have endlessly speculated as to the extent of the psychological damage this discovery must have caused, even going so far as to suggest that this was the reason why Elizabeth never married, but in fact, there is little contemporary evidence to support these theories, and we should be careful not to rely on them.

Elizabeth played what became known as 'the marriage game' with shrewdness and prevarication, keeping her many suitors, both political and personal, in a permanent state of high expectations. This often benefited her realm, since foreign princes, who might otherwise have been aggressive, remained friendly in anticipation of an alliance. Yet, almost always at the last minute, the Queen would find some good excuse for wriggling out of the arrangement. Some of these negotiations dragged on for years: she kept the Archduke Charles of Austria waiting for over a decade, while the French Duke of Anjou courted her for almost as long. Elizabeth blew repeatedly hot and cold, to the exasperation of her advisers, who all understood the desperate need for a male heir to safeguard the continuation of the Tudor line.

I believe that Elizabeth had an aversion to marriage for three reasons. First, having witnessed the breakdowns of several marriages within her own family, she did not see it as a secure state, and feared the controversy it might provoke. Second, as she told Robert Dudley, the man she probably loved more than any other, she had no intention of sharing sovereign power: 'I will have but one mistress here and no master!'

Many women today will understand her determination to retain full control over her life and her desire to have relationships with men while not subsuming herself to them in marriage. For Elizabeth, queenship was her 'career'; she took it enormously seriously, and was not prepared to relinquish any vestige of her power for the sake of a man, however much she might love him. This can be perceived not only as a contemporary dilemma but also as a modem one, particularly hard to resolve if a woman wants children.

Thirdly, and most importantly, in Tudor times, while a monarch was regarded as holding supreme dominion over the state, a husband was regarded as having total dominion over his wife. A queen regnant was still a novelty in England: Elizabeth's own sister, Mary I, had made a disastrous and unpopular marriage with Philip II of Spain, who, expecting to play the traditional conjugal role, had chafed against his wife's attempts to assert her regal authority. Elizabeth had no intention of embroiling herself in such a difficult relationship.

'I am already married to an husband, and that is the kingdom of England,' she was fond of declaring. She solved the dilemma over her marriage by taking a courageous decision, revolutionary for her time, not to marry or have heirs. Nevertheless, as 'the best match in her parish', she exploited her marriageability, using it as a weapon to the advantage of her realm.

She might not have married, but was she the Virgin Queen she claimed to be? The debate has been raging since the 1560s, and scurrilous rumours were rife throughout her reign, fuelled by Elizabeth's own behaviour, which was often condemned by her more sober subjects as scandalous. She would allow Robert Dudley, later Earl of Leicester, to enter her bedchamber to hand her her shift while her maids were dressing her. She was espied at her window in a state of undress on at least one occasion, and in old age, she had a French ambassador squirming in embarrassment for two hours during a private audience by wearing a gown that exposed her wrinkled body to the navel.

Yet many ambassadors, at the behest of prospective royal husbands, made enquiries as to whether or not the Queen was chaste, and in every case they concluded that she was. She herself could not understand why there should be so many racy tales about her, or claims that she had borne bastard children.

'I do not live in a comer,' she told a Spanish envoy. 'A thousand eyes see all I do, and calumny will not fasten on me forever.' A French ambassador who knew her well claimed that the rumours were 'sheer inventions of the malicious to put off those who would have found an alliance with her useful'. Perhaps most tellingly of all, in 1562, when Elizabeth believed she was dying of smallpox and was about to face divine judgment, she spoke of her notorious relationship with Robert Dudley and swore before witnesses that nothing improper had ever passed between them. It is unlikely she would have jeopardised her immortal soul by telling a lie at such a time.

Rumour accused Elizabeth of worse than fornication. In 1560, at a time when Dudley's affair with the Queen was becoming notorious, his wife, Amy Robsart, was found dead, her neck broken, at the foot of a flight of stairs. Dudley was .away at court at the time, but the finger of suspicion pointed at both him and the Queen.

One modem theory is that, Amy's fall resulted not from murder, but from a spontaneous fracture that can occur in someone in the advanced stages of breast cancer. The fact remains that her death was all too convenient. Not for Dudley, who realised immediately that it had put paid to his hopes of ever marrying the Queen, for rumour had long accused him of plotting his wife's death, and he knew very well that Elizabeth would not dare risk" proclaiming herself guilty by association by marrying him, for to do so might well cost her her insecure throne. Nor was Amy's death convenient for Elizabeth, who seems to have been dismayed to realise that her lover was now a free man. In fact, the only person who benefited personally was someone else very close to the throne who may have felt that Amy's death was necessary for Elizabeth's security - and his own. This was William Cecil, later Lord Burghley, who served Elizabeth faithfully for more than 40 years.

Cecil, who had begun the reign as Elizabeth's most trusted adviser, had been ousted from her counsels that year by the ascendant Dudley, a man whose influence he regarded as pernicious. Immediately after the murder, when Dudley, the object of many people�s accusations, was banished from the court pending the outcome of the inquest that would clear his name, Cecil was restored to high favour. The evidence for his involvement in Amy's death is circumstantial, but it is not inconceivable that he was behind a government attempt to frame the favourite.

For many years, people speculated that Elizabeth would marry Dudley. She was closer to him than to any other man. Their relationship endured for 30 years, until his death ended it, plunging her into grief during her hour of triumph after the Armada, in 1588. I am in no doubt that Dudley was the great love of Elizabeth's life, despite the fact that he secretly married twice during the course of their relationship.

Dudley aside, Elizabeth had many other suitors. She was courted by the Archduke Charles of Austria and the Kings of Sweden and France; the King of Denmark's ambassador went about her court wearing a heart embroidered on his doublet, while English noblemen vied for her favour, lavishing sums beyond their means on great houses in which to entertain her. Then there was the sexy French Duke of Anjou, who came twice in person to win the Queen's love: his presence in England was supposed to be a secret, and he was obliged to observe one courtly entertainment from behind a curtain, but since Elizabeth danced with such outrageous abandon and kept waving in his direction, few were deceived. Tongues would have wagged more furiously had it been known that the Queen had visited the duke's bedchamber and brought him breakfast in bed.

It all ended, of course, in disappointment. Anjou was so ardent in his courtship that in the end the Queen had to pay him to go away. She was in her late 40s by then, and wept in Council, knowing that with his departure she had given up her last chance of marriage and motherhood.

Towards the end of her life, she enjoyed a curious and volatile relationship with the headstrong Earl of Essex, 30 years her junior. She may have looked upon him as the son she never had, although he, like Leicester and many others before him, played the adoring lover. When, however, the power-hungry Essex led a revolt against the Queen's government, she did not hesitate to have him executed.

Elizabeth was formidably intelligent and left behind a vast number of letters, poems and speeches: she was a fine orator. We have hundreds of surviving portraits of her, although most conform to the official image painted by Nicholas Hilliard, which depicts her as an eternally young woman, so it is hard for us to assess what she really looked like as she grew older.

She was passionate about hunting, dancing, music and walks in the fresh air. She was also excessively vain, and owned 3,000 dresses, many embroidered with real gems. She had, unusually for her time, bathrooms with piped water and mirrored walls in most of her palaces, which suggests that she had far more than the three or four baths a year with which historians usually credit her. She also had one of the first modem water closets installed at Richmond.

She had a wicked sense of humour: at the solemn creation of Robert Dudley as Earl of Leicester, she mischievously tickled his neck as she fastened on his mantle of nobility. On the other hand, her rages were terrible; one councillor said he would have preferred to fight the King of Spain than face the Queen in a temper. This temper was famously evident when Puritan preachers dared to rebuke her for swearing, or when the text of a sermon was not to her liking. In such cases, she would either shout 'Stop that!' or stamp out of the chapel.

Her indomitable spirit carried her into old age: at 67, 'the Head of the Church of England and Ireland was to be seen dancing three or four galliards' every morning. When she suggested another progress - those long journeys when she travelled through her kingdom - there were groans of protest from her courtiers, so she blithely declared that the old could stay behind while the young ones accompanied her. She had a terror of being seen as old and infirm, fearing that her authority and position as queen might be undermined.

Her physicians and others were of the opinion that her death at the age of 69 was avoidable: her final illness began with what were probably ulcers in her throat, and deteriorated into perhaps either tonsillitis or influenza, but she steadfastly refused to take any medicines or even, for days on end, to go to bed, obstinately remaining on cushions on the floor, sunk in a deep depression. She had told her subjects, 'It is not my desire to live nor reign longer than my life and reign shall be for your good.' Even to the end, she put the needs of her people first.

ELIZABETH: THE ENGLISH ENIGMA, Avenue Magazine, London, 1999

'We princes are set, as it were, upon stages in the sight and view of all the world,' Elizabeth I once remarked. Stages and screens seem to be a perennial place for this particular royal. 'The more I found out about her, the more I liked her,' says Alison Weir, whose recent book The Life of Elizabeth /has sold over 40,000 hardback copies in the U.S. and is probably set to sell even more in the wake of the success of Shekhar Kapur's Oscar-nominated film, Elizabeth.

It is perhaps ironic that the wildly fictitious account of Elizabeth's life portrayed in the film may assist sales of Weir's meticulously researched book (she calls these sorts of films 'modern betrayals of history') but either way, the period has always been associated with richly textured costume, ambition, intrigue and controversy. It was a heady mixture that was often condensed into the life of the court at a time when 16th-century England was asserting a national identity away from continental Catholic Europe. And its ruler was Elizabeth Tudor, daughter of Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, a contradictory, formidably intelligent, capricious woman totally committed to her role. In an age in which a woman's identity was solely bound to marriage and a queen's identity was solely bound to producing an heir, she utterly refused to marry and have children. It was a refusal that ended her own royal lineage. Little wonder, then, that the Elizabethan age has a hold on 20th-century minds.

Historians all over the world have taken issue with the events of the film. Almost every part of the plot, including the love story, is fanciful embell¬ishment or plain untruth. The film-makers, who say they were more influenced by films like The Godfather, defiantly claim that 'historical veracity has not been our main point of contact'.

Yet the film does go some way towards depicting the complexity and colour of the Tudor court. At any one time there were around 1,500 people in attendance, mostly men, usually highly educated, ambitious, and sophisticated. Elizabeth herself could converse fluently in Latin, French, Greek, Spanish, Italian, and Welsh, as could many of her courtiers. There were so many books around that one foreign observer noted, 'The stranger that entereth the court of England shall rather imagine himself to come into some public school of the universities than into a prince's palace.'

The queen was at the centre of what Weir calls 'a great web of patronage', and competition for places and preferment was intense. Everyone always knelt in her presence including her most trusted counsellors such as Francis Walsingham and William Cecil, Lord Burghley. It was considered a major exception when, in the latter part of her reign, she allowed the ageing Burghley to perch on a small footstool in her presence. Many of the courtiers were related to each other and would go to almost ridiculous lengths to be noticed by the queen, their efforts being bitterly dismissed by one longtime courtier as 'empty words, grinning scoff, watching nights and fawning days', although there was enormous fun to be had.

Elizabeth herself had a great appetite for life. She played several musical instruments and loved dancing, doing the daring La Volte, a dance involving the man lifting the woman high in the air, and for that reason, was unbeloved by the Puritans. There were countless plays, banquets, hunts, and masques taking place wherever her nomadic court set up camp. She owned around 60 palaces, many of which she leased to noblemen, and few of which survive today. Highly aware that visibility was crucial, she went on annual 'progresses' during summer months, some 500 members of the court in her wake, taking time to stop and speak with the common folk whom she genuinely wished to meet. Believing that a queen ought to look like a queen, she loved clothes and was almost touchingly vain.

She owned over 3,000 dresses, most of which so heavily bejewelled that when she stood near candlelight, she dazzled onlookers. She took over two hours in the morning to prepare herself, applying the mixture of egg-whites, powdered egg shell, alum, borax, poppy seeds, and water that whitened her skin, and washed her hair in a mixture of wood ash and water. Her undergarments consisted of a stomacher, kirtle, sleeves, underskirt and ruff, all buttoned over a whalebone corset and farthingale, a stiff-hooped petticoat that became wider and wider as the era progressed. For the wealthy, clothes were an obsession, and fashion became ever more fantastic. Men stuffed their balloon-shaped breaches with horsehair, hats were decked with extravagant plumes and the ruffs became more and more elaborate. Velvets, satins, and silks were decorated with real gems. The Queen's Wardrobe Book lists several jewels 'lost from her Majesty's back', and there were 628 recorded pieces of important jewellery in her collection. Her own maids were only allowed to wear black and white so as not to outshine her.

A man's woman, Elizabeth did not encourage wives to stay at court, thus eliminating much female competition. Of all her many trials, it was perhaps the easiest competition to eliminate for she was plagued throughout her reign by Catholic plots against her throne, taut foreign relations and a difficult parliament who had become used to the power invested in it by her father, Henry VIII. The clothes horse was essentially an extremely serious, able woman. In 1603, ill and depressed, realizing that death was near, she wrote in sad metaphor, 'All the fabric of my reign, little by little, is beginning to fail.' She died not long after but the glories of her legacy have not.

From the Slough Express, 25th March 1999

ELIZABETH I ON FILM: A PERSONAL VIEW BY ALISON WEIR

My views in this article may be staunch and thought-provoking, but they are also intended to be the springboard for a lively discussion.

As someone who is passionate about the past, I am an avid viewer of historical films and TV dramas, and enjoy watching some of them on DVD again and again. But as a historian, my expectations are often disappointed, because I am probably more aware than most people of the factual errors that are committed by film makers. Their brief is, of course, to reconcile historical accuracy with dramatic licence and produce a visual interpretation that is commercially viable, and I have no problem with that - even Shakespeare did it! It is when the facts are distorted to an unacceptable degree, so as to render the plot or the ambience incongruous, that I start breathing fire.

In my professional capacity, I research extensively from contemporary sources, seeking always to corroborate the evidence, and carefully drawing considered conclusions in the quest to achieve historical accuracy. I am therefore horrified at some liberties taken by film makers. History, goes the old saying, is stranger than fiction, and it is full of the most wonderful stories. I therefore see little need to embellish or alter the facts, especially when they are well known. There is plenty of scope for invention where there are gaps in our knowledge. For example, we don`t know for certain that Elizabeth I was the Virgin Queen that she claimed to be; as a historian, I believe that the evidence strongly suggests that she was, but we can never know for certain, so I have no problem with films showing her romping in bed with the Earl of Leicester. I also think that it is perfectly legitimate, in the interests of creating a good drama, to telescope events or create symbolic scenes.

There is no doubt, though, that history is nowadays increasingly `dumbed down` in many respects, and that film and TV production companies have a lot to answer for. The attitudes of some towards their audiences can border on the patronising. One researcher, discussing my contribution to a programme, asked me to use `language that a BBC audience can understand`. It`s demeaning, another has claimed, to have to keep to the facts - notwithstanding the minor detail that a good percentage of the audience will already know a great deal about the subject and will easily spot howlers. Make a TV drama about Elizabeth I, and the ratings are bound to be good because so many people are fascinated by her, but these ratings won`t reflect the negative views of many who tuned in - I hear them all the time, in letters and emails, and from audiences at my events. Thus it is that intelligent and well-informed audiences continue to be sold short.

Also sold short are those who know little or nothing about the subject, and who might never progress beyond celluloid to a history book. Film is a powerful and compelling visual medium, and so many people believe that what they see is an accurate portrayal of history. Film-makers - like historical novelists (and I speak from experience here) - have a responsibility to their audience to ensure that their works have historical integrity.

Many of the historical personages about whom I have written have been the subjects of films and TV dramas, and none more so than Elizabeth I. Since 1912, when Sarah Bernhardt (above, left) very theatrically played her in the silent French movie, Les Amours de la Reine Elisabeth, there have been many famous portrayals. A little known British silent film of 1923, The Virgin Queen, featured the appropriately aristocratic Lady Diana Manners in the title role.

In 1937, Flora Robson (above, right) played Elizabeth in Fire Over England, which was dismissed as `swashbuckling nonsense` by one critic; in 1940, Robson reprised the role in The Sea Hawk.

It was Hollywood that gave us what is arguably the most famous screen portrayal of Elizabeth, with Bette Davis playing the Queen in two films, The Private Life of Elizabeth and Essex (1939, above, left), with Errol Flynn as Essex, and The Virgin Queen (1955, above, right). Both films received the glamorous, jingoistic and anachronistic treatment that was the studios` typical approach to English history, and Davis`s studied and overplayed Elizabeth is merely a two-dimensional caricature of her historical counterpart.

Another unashamedly romanticised film about Elizabeth was Young Bess (1953), based on Margaret Irwin`s novel about the future Queen, starring Jean Simmons (above, left), who - beautiful as she was - bore no resemblance to the youthful Elizabeth.

It was the BBC who, for me, produced the definitive Elizabeth, with Glenda Jackson`s brilliant and inspired performance in the 1971 TV series, Elizabeth R. (above, centre); not only was the script based on original historical sources, with authentic costumes and settings, but Jackson`s masterly performance captured all the facets of the Queen`s complex personality. Glenda Jackson reprised the role acting opposite Vanessa Redgrave in the feature film Mary, Queen of Scots (1971, above, right). This is not as historically accurate as Elizabeth R - it has the two queens meeting, which they never did in real life - but it is well-acted, well-scripted and worthily produced.

Sadly, the same could not be said for Elizabeth, starring Cate Blanchett (above, left), which hit the big screen in 1998. As one critic said, this film was strictly for the MTV generation. It contained so many inaccuracies that it would be impossible to list them all here. To give just a few examples: the Duke of Anjou, who came courting the Queen, was portrayed as a transvestite, when in fact it was his brother, Henry III of France (previously Duke of Anjou) who enjoyed cross-dressing; the Duke of Norfolk was played as a menacing, deadly threat to the throne when in fact he was a dilatory and inept plotter; Sir Francis Walsingham was even shown murdering Marie de Guise, Queen Dowager of Scotland, and notwithstanding the fact that she died some years before he rose to power, the very idea was so far-fetched as to be ludicrous. The plot against Elizabeth was a confused mish-mash of several conspiracies, but where was their real-life focal point, Mary Queen of Scots? The setting was jarringly anachronistic, by more than three hundred years - how could anyone think that Romanesque Durham Cathedral could in any way resemble a Tudor palace? - and the costumes unauthentically casual. No one would have appeared at court without a ruff, let alone danced with the Queen in an open-necked shirt. One might wonder if this was all deliberate or just sheer sloppiness. Regrettably, Blanchette reprised the role in the even more dismal Elizabeth: The Golden Age (2007, above, right), which showed Sir Walter Raleigh winning the Armada almost singl-handedly, when in fact he wasn't even there. And for some unknown reason, the Elizabethan court was set in a medieval cathedral. I don't think I will ever forget collapsing with laughter at the sight of Elizabeth clanking around in full armour at Tilbury.

Fortunately, in the same year, 1998, the silver screen did benefit from a brilliant portrayal of Elizabeth. In Shakespeare In Love, Judi Dench (above, left) spent a total of just eight minutes on screen in the role, and delivered an utterly commanding performance.

Since then, there have been two highly publicised British TV drama series about Elizabeth. By far the best was the acclaimed Elizabeth I (2005) with Helen Mirren (above, centre), who gave an admirable account of herself in the title role. As a historian, I was particularly impressed by the computer-generated recreations of the Tudor palaces. Best forgotten in my view is The Virgin Queen (2005), a confused drama with Anne Marie Duff (above, right).

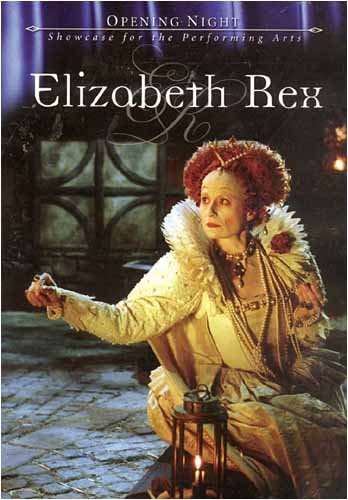

Many other actresses have played the Virgin Queen over the years - Ellen Compton (The Loves of Mary, Queen of Scots, 1923, above, left), Athene Sayer (Drake of England, 1935), Florence Eldridge (opposite Katharine Hepburn in Mary of Scotland, 1936, above, centre left), Peggy Thorpe-Bates (in the UK TV series Queen`s Champion, 1958), Irene Worth (Seven Seas to Calais, 1962, above, centre right), Gemma Jones (in the UK TV series Kenilworth, 1967), Judith Anderson (opposite Charlton Heston in the US TV series Elizabeth the Queen, 1968, above, right), Lalla Ward (in The Prince and the Pauper, 1977, below, left) and Diane D`Aquila (in the Canadian TV production Elizabeth Rex, 2003, below, centre). Elizabeth has even been played by a man, Quentin Crisp, in the film of Virgina Woolf`s novel Orlando (1992, below, right).

For me, the best screen Elizabeth remains Glenda Jackson`s - but I`m sure many will agree that for sheer enjoyment, Miranda Richardson`s inspired Queenie in Blackadder (1986) takes some beating!

I would like to see film makers demonstrating more respect for history and the intelligence of their audience. There is a huge popular interest in history, but we need to distance ourselves from the modern received wisdom that it is better to have inaccurate history than no history at all. After all, history is fascinating and astonishing in its own right - as I often quote, you could not make it up!

ARTICLE FROM THE MAIL ON SUNDAY, 13th SEPTEMBER, 1998

by Danae Brook

ELIZABETH I IS KNOWN AS THE VIRGIN QUEEN, SO WHY DOES A NEW FILM SHOW HER HAVING SEX WITH A COURTIER?

The two bodies are naked, intertwined. Young lovers in the heat of passion, cocooned in the intimacy of a huge double bed from which curtains cascade. It's the sort of scene that is only too familiar in Hollywood and at first glance it would be no more shocking than most. But what is truly startling is that the woman on screen is Elizabeth I, the 'Virgin Queen'. The sex scenes form a key part of a controversial film, Elizabeth, produced by Working Title, the makers of Four Weddings And A Funeral.

The new film rejects the established view that the Queen remained a virgin throughout her life. Instead she is portrayed as a woman who had a torrid, sexual affair with Lord Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, but later coldly invented the myth of herself as a chaste monarch after her

romance with him had died. The interpretation will stun audiences, and has already attracted criticism from historians. But director Shekhar Kapur - who has never before worked in this country or made a film which was not in the Indian language - defended his interpretation of Elizabeth's life at the premiere of the film last week at the Venice Film Festival.

Kapur, director of The Bandit Queen, once banned by the Indian government for its brutally sadistic scenes, said: 'Historical facts are only a constraint if you stick to them. If you are saying I have to tell history absolutely correctly, then I can't make an emotional movie. You have to have the courage to interpret. I don't mind turning history on its head, if that's what people think I'm doing. Why not take another look at the facts? In this day and age, we're modern people, our education says we must question everything, yet we never question the fact that here was a woman, who lived 400 years ago, with four very strong, very well-documented relationships, who was said to be a virgin. Why? We came up with the idea that her virginity was a political statement, and not a physical fact.'

But historians do not agree. Although there is little doubt that Dudley was the love of Elizabeth's life, few think the relationship was consummated. Historian Alison Weir, who has just published a book about Elizabeth and her courtiers, thinks Kapur has taken 'a lot of liberties with the truth' and dismisses some of his claims as 'nonsense'.

In the film, Elizabeth, played powerfully by ravishing Australian newcomer Cate Blanchett, has a full sexual relationship with Dudley, whom she had appointed her Master of Horse. According to the script by writer Michael Hirst, who took a degree in History at Oxford, the romance appears to date from just before she learns she is queen, and continues for a tempestuous decade into her reign until, believing Dudley to be part of a conspiracy against her, she finally banishes him from her bedchamber, if not her heart, and invents the myth of herself as a virgin.

Filmed in the vibrant colours and rich textures of Indian cinema, against stunning locations from Haddon Hall in Derbyshire to Durham Cathedral, the entire movie is a sensual adventure in which Elizabeth takes centre stage. The Virgin Queen is seen as wanton seducer and heretic (she, as a Protestant, was taking over a Catholic country and faced enormous opposition from the Pope, who excommunicated her, calling her 'heretic and whore' as she herself spits out in one scene).

In the opening shots, Dudley (played by Joseph Piennes) and Elizabeth are dancing and flirting in the fields outside Hatfield House, Hertfordshire, where Elizabeth's half-sister, Queen Mary (played as an embittered, cancer-ridden fiend by Kathy Burke), exiles her from court. Elizabeth's coterie of friends and ladies-in-waiting, and the cinema audience, are left in no doubt that they are lovers, or about to become so.

Within the first half hour of the film, once Mary has died of the tumour she hoped was a pregnancy, and Elizabeth has acceded to the throne, the new Queen is taking Dudley to her bed. On the night of her coronation (in 1559), she brazenly picks him out to dance with her, causing ripples of excitement when he publicly proclaims their intimacy, by whispering in her ear, holding her tightly against him. She responds ardently, their language - and body language - unmistakably that of lovers. After the banquet, Elizabeth retires to her bedroom to await Dudley. Her ladies-in-waiting giggle conspiratorially as he approaches. The traditional silken bed drapes are pulled apart, the camera lingers lovingly on their two naked bodies in obvious and passionate embrace.

Such graphic scenes may stick in the throat of historians and anyone who remembers their history lessons, but Kapur is unrepentant.

'It's exciting to take another look at accepted views,' he says. 'Controversy has never worried me. Elizabeth was an immensely powerful woman. To retain that power she had to reject her own sexuality. That doesn't mean she had no sexuality to start with. To assume the mantle of power she felt she had to give up any hope of personal love. It's a sad story as well as an exciting one.'

The sexual relationship between Elizabeth and Dudley is not the only controversial aspect of Kapur's film. The Duc d'Anjou is played as a cross-dressing transvestite and Walsingham, Elizabeth's trusted but Machiavellian adviser, portrayed as a homosexual. But Alison Weir maintains there is no evidence to support the film's rein-terpretation of history. 'There are three specific reasons why we believe Elizabeth lived and died a virgin,' she says. 'First, it would have been political death if she wasn't. She had an insecure throne and had to put her reputation and her religion first. Second, because of her status, many foreign princes sought her hand in marriage and she was subjected to relentless investigations by their ambassadors. Most were Catholics, trying hard to discredit her, but they never managed to. Finally, four years into her reign, when she was at the height of her love for Dudley, she almost died of smallpox and declared herself a virgin [misquoted here]. It's unthinkable she would have perjured herself on what she believed to be her death-bed.'

But in history according to Kapur, the love affair with Dudley continues until he apparently betrays Elizabeth. The pivotal moment comes when he is implicated in a plot against her instigated by the Duke of Norfolk, involving her marrying the King of Spain. Elizabeth's Master of Spies, Lord Walsingham, uncovers the plot. The sinister Norfolk is beheaded, the conspiracy quelled and Dudley's physical love finally and completely renounced. As Elizabeth chops off her hair, covers her face and hands in white paste and becomes the Virgin Queen before her subjects, she says to a tearful lady in waiting: 'I have become the Virgin.' And to her adviser Sir William Cecil (played by Richard Attenborough), who has long urged her to marry to secure her throne: 'Observe, I am married to England.' The words have powerful echoes of her famous declaration: 'I know I have the body of a weak and feeble woman, but I have the heart and stomach of a king.'

Blanchett, who effortlessly transforms from flirty girl to flinty Queen, says: 'Elizabeth was fiercely loyal as a person, but she married England. I think it's terrifying what you have to wrench out of your heart when you take on public responsibility.'

But for all the undoubted glamour and vivid drama of the film, released in Britain on October 2, there will be many who resent the explicit reinterpretation of the life of one of England's most cherished monarchs.

ARTICLE FROM THE COVENTRY EVENING TELEGRAPH, 8 MARCH 1999

QUEEN ELIZABETH I really was a virgin, although a great flirt, according to best-selling royal biographer Alison Weir. Ms Weir, who will be speaking at Coventry's first literary dinner later this month, has no time at all for recent romantic films about Elizabeth and her entanglement with Robert Dudley, to whom she gave Kenilworth Castle. The author plans to set the record straight when she comes to St Mary's |Guildhall in Bayley Lane - the same hall where Elizabeth herself once demanded that her great rival, Mary, Queen of Scots, 'be safely kept and guarded'.

Ms Weir said: "This latest film about Elizabeth, starring Cate Blanchett, is based purely on a terrible late-20th-century viewpoint and

bears no relation to the facts. Personally I am convinced that Elizabeth remained a virgin queen all her life. She was a dreadful flirt, which gave rise to scurrilous rumours, but as she said herself, 'I do not live in a corner, A thousand eyes see all I do.'

Even on her deathbed Elizabeth denied that anything improper had ever taken place between herself and Robert Dudley, who she created Earl of Leicester, and to whom she gave extensive lands in both Kenilworth and Warwick.

Ms Weir said: 'In the late 20th century we do not understand the significance of a deathbed confession. In 1562 it would have been unthinkable even for a queen to lie as she faced divine judgement.'

The popular historian is one of three writers booked to give after-dinner talks in the Guildhall at 7.30pm on March 24.

Alison Weir decided to make further studies of Coventry after accepting the invitation to speak in the guildhall. As well as talking about her book, she hopes to have time to remind people about the significance of the city's past. She said: 'Perhaps few citizens today realise that between 1456 and 1459 Coventry was virtually the seat of government in England when Henry VI and his forceful wife, Margaret of Anjou, moved their court to Coventry Castle during the Wars of the Roses.'

MISCELLANY

I have written about Elizabeth I in four non-fiction books. Her childhood is covered in The Six Wives of Henry VIII, her formative years in Children of England, her reign in Elizabeth the Queen, and her relations with Mary, Queen of Scots in Mary, Queen of Scots and the Murder of Lord Darnley. All are in print and widely available. Her path to the throne is the subject of my second novel, The Lady Elizabeth., and the sequel, The Marriage Game, will be published in June 2014. Elizabeth also features in my novel, A Dangerous Inheritance.

There is an error in Elizabeth the Queen - it is stated that her coronation took place on 15 December 1559, and it should of course read 15 January 1559.