Books

Innocent Traitor (2006)

I am now a condemned traitor. I am to die when I have hardly begun to live.

Above: Unused U.K. paperback jacket design, and two stills from the jacket shoot at St Bartholemew's Church, Smithfield, London.

I chose the costumes for my Hutchinson fiction jackets, and attended the shoots.

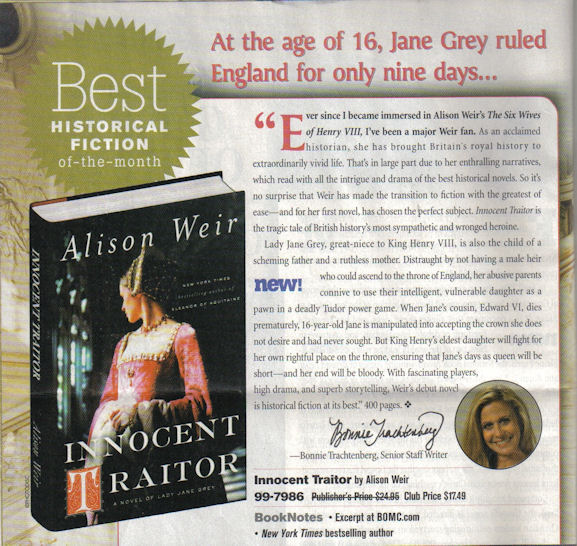

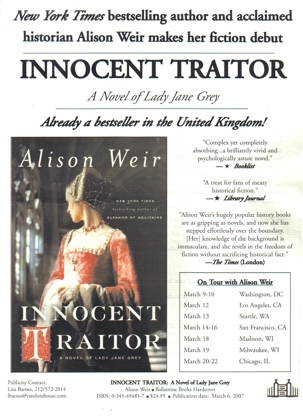

Book of the Month Club News, Spring 2007

(Right: Book of the Day on British Monarchy on Instagram, 12th February 2015)

"Her brave move is a success… Compellingly told from various points of view, this story is bolstered by fabulously gruesome historical details." (The Sunday Times)

"The story is so compelling and horrible that even a reader well-acquainted with it will be gripped. It reads as easily as a thriller, but the reader may be assured that this is only lightly fictionalised history… This is a novel that will grip readers and give great pleasure." (Allan Massie, The Scotsman)

"Alison Weir's hugely popular history books are as gripping as novels, and now she has stepped effortlessly over the boundary… Her knowledge of the background is immaculate, and she revels in the freedom of fiction without sacrificing historical fact… If you don`t cry at the end, you have a heart of stone." (The Times)

"Weir invests [the story] with fascinating detail… Weir manages her heroine`s voice brilliantly, respecting the past`s distance while conjuring a dignified and fiercely modern spirit." (The Daily Mail)

"Excellently documented by Weir, as we would expect, and she gives us a meaty flavour of… one of the bloodiest and most dangerous periods in history… This is an impressive debut. Weir shows skill at plotting and maintaining tension, and she is clearly going to be a major player in the historical fiction game." (The Independent on Sunday)

"Splendid... In giving narrative voice to her subjects Alison Weir brings us into emotional contact with them in a way that an unadorned historical account does not." (The Boston Globe)

"[Lady Jane] Grey's short life is vividly recreated in this moving and multi-faceted narrative." (The Sunday Times, paperback review)

"Engrossing, suspenseful... Enormously entertaining... An enthralling story." (The Washington Post)

"Sensitive and fast-paced … [Weir] shines in portraying Jane as a highly intelligent, angry, determined teenager who met a terrible end.”

(U.S.A. Today)

"Complex, yet brilliantly absorbing... A brilliantly vivid and psychologically astute novel" (Booklist - starred review)

"A treat for fans of meaty historical fiction. Well written and researched, it succeeds as a thoroughly involving novel by bringing a disparate, sympathetic group of characters to life." (Library Journal - starred review)

"And engaging novel, full of vivid details. Poignant and harrowing... A gripping finale." (The Seattle Times)

"What an excellent debut it is… Weir is an exceptional storyteller, and relates events in a way that cannot fail to keep readers of historical fiction enthralled." (Waterstones Books Quarterly)

“[Weir] makes a familiar story vibrant and fresh.” (The Atlanta Journal-Constitution)

Historical expertise marries page-turning fiction in Alison Weir’s enthralling debut novel, breathing new life into one of the most significant and tumultuous periods of the English monarchy... Alison Weir uses her unmatched skills as a historian to enliven the many dynamic characters of this majestic drama. Innocent Traitor paints a complete and compelling portrait." (BookBub)

TEN HISTORICAL BOOKS ABOUT TREASON AND REBELLION, 2016

Thanks to Bookbub for featuring Innocent Traitor!

https://media.bookbub.com/blog/2016/11/03/historical-fiction-books-about-treason-and-rebellion/

You can read my article, Lady Jane Grey: The Nine-Day Queen, in the February 2019 issue of History Revealed magazine.

FROM HISTORICAL FACT TO HISTORICAL FICTION, U.K., 2006

Innocent Traitor, originally titled Light After The Darkness, is my first published novel. It`s been called `a brave move` from writing non-fiction to fiction, but in fact it was never originally written for publication - I embarked on it purely for enjoyment. Back in 1998, when I was researching my biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine, my workload was light because I had already done a considerable amount of earlier research on Eleanor, and was basically updating it. Therefore I had some time on my hands - time that would prove to have been more than productive.

Back in the years when history was just an enjoyable hobby, I had tried my hand at writing all kinds of things: non-fiction, family trees, plays and historical novels. I have always been a great fan of good historical novels - Anya Seton, Norah Lofts and Hilda Lewis remain my favourite authors. Inspired by them, I wrote several novels all those years ago, on subjects as diverse as Anne Boleyn; Edward III`s mistress, Alice Perrers; a family saga set in a medieval manor house; and Isabella Marshall, a thirteenth-century royal countess. None, however, were suitable for publication, and I never even thought of submitting them. Later on, I became a published historian, and for many years focused entirely on adhering to the strict disciplines of historical interpretation and reining in my formidable imagination!

Writing the biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine, however, was my first attempt at recreating the life of a medieval woman, piecing together myriad fragments in an attempt to reconstruct a credible story - such is the challenge of mediaeval biography. It was, to some extent, a frustrating exercise, because some things are unknowable: no one thought to record what the beautiful Eleanor actually looked like, for example, or why she separated from Henry II, and I found myself itching to fill the gaps, knowing that a historian could only overstep the bounds of speculation at her peril. We can only infer so much from historical sources.

With time on my hands, it occurred to me that I could fill it by writing a novel, and thus allow my imagination to run riot. But which subject to choose? Eleanor was off limits, because I did not wish to write about her in the fictional sense when I was striving for accuracy and credibility in my biography; and my leisure time was restricted, so it had to be a compelling but short story, and preferably one that I was familiar with. A reader had recently written suggesting that I write a biography of Lady Jane Grey, the ill-fated Nine Days Queen of England, but I had discounted that idea as I had written about her two years previously in my book Children of England: The Heirs of King Henry VIII. It occurred to me now, however, that Jane`s tragic tale would be an ideal subject for a novel: it was short, it was dramatic and unbearably poignant, and I knew it well, having done all the research for the earlier book. Immediately, I got down to work, and three months later, the novel was finished.

I must stress again that, when I began writing, I did not intend to submit my novel for publication. History is still a hobby for me, as well as a profession, and I undertake various projects as a hobby in my spare time, when I have any. This was to be another such - and I was going to write it for fun. But as the book progressed and the tale unfolded, it occurred to me that it was such a good story that it might be worth showing it to my agent. Of course, being unable to judge my own work, I had no idea whether or not I could write fiction, but it was worth a try.

I duly submitted the finished manuscript, which was written in the third person and the past tense, and entitled Light After The Darkness, using one of Lady Jane Grey`s own quotes. My agent thought it a riveting story, but said I should come down off the fence and forget I was a historian, as the book read like `faction`: and he was right, for I had felt the need to explain everything factually, instead of weaving the facts seamlessly into the narrative and the dialogue. By then, though, I had no time to work any more on the novel, so I put it away and forgot about it.

Fast forward five years to 2003, when after completing my biography of Isabella of France, I took a month off, which I used to rewrite my novel, this time using the first person and the present tense, a format in which no history book could ever be written. Thus I hoped to distance myself from my non-fiction works. It was at this stage too that I renamed the book Innocent Traitor, feeling that its original title was a little too obscure. It was this version of the novel that was commissioned for publication by Hutchinson.

Writing historical fiction had given me an exhilarating sense of freedom: no longer did I have to limit what I could infer from contemporary sources, but I could let me fertile imagination hold sway. Yet I feel strongly that the historical novelist has a great responsibility towards his or her readers, because a lot of people (myself included) discover an interest in history through reading historical novels, and unlike me, some never make the transition to history books to find out what really happened. Because of this, therefore, and because I want my readers to trust me, I have scrupulously adhered to the facts where they exist - whilst of course dramatising each scene - and used my imagination where they do not. History does not always record people`s motives, emotions and reactions, nor the intimate details of their relationships or their sex lives, so there is plenty of scope for invention there. Even so, what is written has to remain credible: people must behave in keeping with what is known of their characters, and the setting must be authentic.

Too many historical novels fall down because the author simply has not done enough background research. I am fortunate in that I have studied the Tudor period, in which my novel is set, for more decades than I care to remember, and feel quite at home in it - probably more than I do in the twenty-first century! Yet I still have found it necessary to look up minor details in the interests of authenticity, such as the kind of books that were printed by the Caxton press in Jane`s time, or the layout of the rooms at Bradgate Park, her family home, now a ruin. One can`t afford to be sloppy because this is `just` fiction.

How far dare one manipulate the facts in a novel about a real historical personage who may be quite well-known? My feeling is that you should have some historical evidence, however flimsy, on which to base that aspect of the plot. For a historian, such evidence may not be convincing, but it might be a gift to a novelist. For example, in The Other Boleyn Girl, Philippa Gregory has Anne Boleyn, desperate to have a son, contemplating incest with her brother because he is the only man who can safely be relied upon not to betray their intimacy to others. The historical Anne was indeed charged with incest in the indictment drawn up against her, and while other evidence strongly suggests that these were trumped up charges, a novelist may use them as the basis of a good plot. Again, the issue of Elizabeth I`s much-vaunted virginity has been endlessly debated by scholars, but we are unlikely ever to discover the truth, so in my view it is quite legitimate for novelists such as Susan Kay in Legacy and Robin Maxwell in The Queen`s Bastard to depict the Queen having a full sexual relationship with the Earl of Leicester.

Where I have invented material in Innocent Traitor, I have made that clear in the Author`s Note at the end of the book. For example, we do not know the identity of the female quack who was brought in to administer arsenic to the dying Edward VI, but in Innocent Traitor, I have fleshed her out into a real character. And there are one or two dead bodies in the novel that are not historically documented! Conversely, passages that may sound far-fetched are often likely to be based on fact, such as the discovery of an arrest warrant for Queen Katherine Parr, which was fortuitously found in a corridor. This information comes from John Foxe`s Book of Martyrs, and until comparatively recently, most historians questioned its veracity; now, however, most accept it as essentially factual. There is, however, no evidence that it was Jane who found that warrant, although she was in Katherine`s household at the time, and it seemed to me credible that a child would take an important looking document back to the Queen, who was looking after her and would know what to do with it, rather than try to discover where it came from herself.

We don`t know why the historical Jane refused to sleep with her husband after their marriage had been consummated, or why she would not make him king consort, but in my novel, in one of the most shocking sequences it contains, I have offered what I think is a convincing reason for this. Writing this scene posed a real challenge, as I had to forget who might in time be reading it and focus on making it as graphic and realistic as possible. To give it more impact, earlier sex scenes in the book were cut.

I chose to write my novel with several different narrators. There were originally sixteen, but there are now eight, the chief of whom are Jane herself, her mother and her nurse: in the interests of clarity, my editors felt that the strongest characters should remain, and that they should tell the parts of the story that had been told by the `lost` narrators. Altering the book in this way changed its mood somewhat; two male voices, Thomas Seymour and Guildford Dudley, had provided an earthier, more humorous aspect to it; without them, this is a much darker tale.

Using a variety of narrators is an ideal device for deploying dramatic irony and making the reader privy to plots, secrets, feelings and motives. One reviewer felt that characters who were secretive and duplicitous in real life should have been the same with the reader, withholding crucial information, but it was my intention from the first that every character should be entirely open with the reader, thus making the latter a party to all the intrigues.

After routinely revising ten non-fiction books over the years, I thought I knew all there was to know about the editorial process, but with this book I discovered that fiction editing is very different. I must add, however, that the editing of this novel proved to be an interesting and enriching experience, not least because I was under the direction of a highly talented and supportive team at Hutchinson. It really was a case of going back to square one and learning a little humility! And my initial fears that taking on board others` creative suggestions would mean that the novel would no longer be `my` book proved groundless, because it was I who did all the structural and line-by-line revisions, and who converted narrative into dialogue and action. I am happy to say that I emerged from this process having learned a great deal that will be of benefit to me in the future, and that I will always be grateful to my very patient mentors! Thus armed, I intend to write more novels in the future, side by side with my non-fiction books. I consider myself very privileged to be able to do both.

People often ask me what it is that makes the Tudor period perennially fascinating to me and to so many others. I think there are several reasons. First, history is about people, and you rarely come across such vivid and charismatic characters as the Tudors themselves. A king with six wives, two of whom he had beheaded? You couldn`t make it up. Which leads me to the second reason, which is that this is one of the most dramatic and colourful periods in history. It`s sumptuous, too - as one reader enthused recently, `Oh, the clothes!` So maybe that`s the appeal for a generation addicted to conspicuous consumerism. Third, this is the first period in English history in which the art of portraiture flourished: thanks to the genius of Hans Holbein and others, we know what the leading personalities of the period looked like. This brings the age to life in a very personal way. And fourth, there is far more surviving documentation of people`s private lives and feelings for the Tudor era than for the mediaeval period, so we know these kings and queens in a way that would be impossible in respect of their forbears. All these factors combine to make Tudor England especially fascinating to us.

One of the great joys of writing my novel was being able to get inside the heads of my characters and actually be them and inhabit that long-gone world. In order to do this, I have drawn on a wealth of research material gathered over many years. It has been said that my portrayal of the ageing Henry VIII is unusually sympathetic, but there is evidence that Henry could still be avuncular and affable in his declining years, and I have written about him as Jane, a young child, would have seen him. We know, for example, how affectionate he could be towards his own children, how he comforted Lady Carew as they watched the Mary Rose go down with her husband on it, and how his daughters, Mary I and Elizabeth I, revered his memory. Of course, there was another, nastier side to Henry, but he is so often portrayed as a caricature of his real self that I wanted to show him as a rounded human being, the many-faceted man who is the subject of my book Henry VIII: King and Court.

Writing Jane`s passages posed an even bigger challenge, because the early ones had to be related by a young child. The sophistication of her language has prompted some startled comments, but again it is founded upon facts. There was no concept of childhood as a separate phase of development in Tudor times: children were regarded as miniature adults who had to be civilised as soon as possible so that they could join an adult world in which life expectancy was much shorter than it is now. Thus boys could go into battle as young as eleven, and girls could marry and cohabit at twelve, boys at fourteen. In conjuring the voice of a four-year-old, I looked back to the kind of conversations I had had with my own highly intelligent daughter when she was that age, and bore in mind historical examples of children`s speech, such as that of the three-year-old daughter of Charles I who, on her deathbed, piped up unprompted, `Lighten mine eyes, O Lord, lest I sleep the sleep of death.` And who can forget the perspicacious Elizabeth I, not yet three, asking, `Why Governor, how hath it, yesterday Lady Princess one day, and today but Lady Elizabeth?` Jane herself was unusually precocious too.

One of the most unattractive characters in the novel is Jane`s unkind and overbearing mother, Frances Brandon. It would have been easy to portray her as a stereotypical abusive parent, but I wanted her to be more than this, so on occasion we see her as that little bit more human. And while some have taken issue with her change of heart at the end of the book, how else could one explain her presence at court, except of course as a self-seeking monster? She was, after all, Jane`s mother, and although her feelings towards Jane were complicated, she had in fact pleaded for her life on an earlier occasion.

The real mother figure in the book is Jane`s nurse, Mrs Ellen, and there is a lot of me in Mrs Ellen. When I wrote this book originally, my daughter was the same age as Jane had been when she was in the Tower of London, so I could empathise powerfully with Mrs Ellen, who loved her charge as if she were her own flesh and blood. In fact, writing the final sections of the novel was a searing experience because I was so vividly aware of how beautiful and innocent young girls at the dawn of womanhood can be. Looking at my own child, I could imagine all too vividly how I would feel if I were Mrs Ellen and she my doomed charge.

I have been told that one aspect of this book that stands out is the contemporary emphasis on etiquette and tradition, which added to the many constraints that were placed upon children and women. Many have found the unquestioning obedience of children to their parents, and the willing subservience of wives to their husbands, quite startling, but these were accepted norms in life back then, and it is the novelist`s job to reflect that. Readers may - and do - draw their own comparisons.

There are too issues in the book that have a relevence for a modern audience. Beside that of feminine equality, there is the strong and horrifying theme of child abuse, which is all the more shocking because much of what we would see as child abuse today was condoned in Tudor times: there existed a strong feeling that sparing the rod really did spoil the child. Even when parents were excessively unkind, few ventured to question their absolute authority over their offspring, as becomes clear in the book.

Another strong theme in the novel, which also has relevence for us today, is religious fundamentalism. After the Reformation, you were either Catholic or Protestant: there was no middle ground, and no concept of religious tolerance. Prior to the terrible events of 9/11, it was difficult to convey to a modern, secular readership just how strong an influence religion had over people`s lives in Tudor times; since then, however, we have had to confront the reality of religious fundamentalism within our own society, and thus are better able to understand the issues that dominated the thinking of men and women living four hundred and fifty years ago.

The major challenge to any author embarking on a historical novel is the use of language. There are tough choices, and you will never please everyone. You could, if you were stupid enough, adopt pseudo-Tudor speak and alienate your readers with words and phrases such as `prithee`, `dost thou` or `hey nonny nonny`; or you could go to the other extreme, as Suzannah Dunn does in The Queen of Subtleties, where she has Anne Boleyn calling her father `Dad`. Surprisingly, that worked quite well, thanks to the excellent characterisations in her novel, but one could also use modern, plain speech to the same effect, as I have done to some extent in Innocent Traitor.

Having spent many years studying Tudor sources, I am fortunately familiar with forms of language in use then (although we can never fully know how people actually spoke, only how their words were written down, which may not be the same thing). Wherever possible, I used my characters` own historical quotes, modernising them slightly in places so that they would not stand out unduly in a text that paid lip service to contemporary language, yet was also inspired to a degree by the works of historical novelists as diverse as Hilda Lewis and Tracy Chevalier. In order to appeal to as wide - and as young - an audience as possible, I confess deliberately to using a few modern idioms where I think they sound better than their Tudor equivalent, even if they are anachronistic. I was gratified to find that, even though one reviewer was unhappy with that, another had said that I had got the language just right. In my next novel, also set in the sixteenth century, I am using the past tense and the third person, which will allow for greater versatility in the use of language.

That novel, The Lady Elizabeth, will tell the story of the young Elizabeth I in the tense and dramatic years prior to her accession. And this time, I am going to make a leap off that fence, throw off my historian`s hat and do something very daring….

In the meantime, it is my sincere hope that the sad and poignant tale of Lady Jane Grey will both move and horrify you, and perhaps even bring a tear to your eye. And because it is told in the present tense, and is happening now, as it were, even if you already know the story, you may wonder, as I did when I was writing it, and several readers have done since, whether or not it might - just might - end differently.

HISTORY VERSUS FICTION – THEY`RE ALL GOOD STORIES

By ALISON WEIR, U.K., 2006

Ever since I first read the wonderful historical novels by Anya Seton, Norah Lofts and Hilda Lewis – to name a few - in my teens, I have wanted to write a historical novel. In fact, I wrote quite a few back then, some about well-known people such as Anne Boleyn, others fleshing out more obscure subjects such as Alice Perrers, mistress of Edward III, or here and there a family saga spanning the centuries, or even a historical murder mystery set in Chambercombe, an ancient house in Devon. But my life took another direction, because my overriding interest was in history itself, which can be even more compelling than fiction, and eventually I found myself publishing a series of non-fiction books on kings and queens, telling stories, but sticking strictly to the facts and what I could infer from them. I may account myself a historian, but I`m essentially a story-teller. It`s an old-fashioned approach to history, but it certainly brings it to life for many people.

However, there are more ways than one of telling stories. One of my chief character traits is an active – some would say overactive - imagination, and I`m always wondering, what if….? Back in 1998, when I was researching Eleanor of Aquitaine, I was constantly aware of the many gaps in the historical record of her life, as I was fitting fragments of information into place like pieces in a jigsaw to arrive at a credible account of the life of that remarkable lady, and endlessly speculating on what had really been the truth. The process reminded me of those early novels, in which I had woven tales around little-known historical characters, using my imagination to flesh them out and fill in the gaps; and it occurred to me that writing fiction would allow me more scope for story-telling. I could flesh out those fragments and give full rein to theories I dared not ever voice in my non-fiction books.

Once the idea was born, I got down to work at once – in my spare time - on the novel that would one day become Innocent Traitor, and which tells the tragic story of Lady Jane Grey. Only then it was called Light After The Darkness, using words that Lady Jane wrote in the Tower of London; later, it was agreed that this title would be too obscure. I finished the novel in about two months, working two hours a day, and researching Eleanor the rest of the time.

When the novel was finished, it occurred to me to submit it for publication, but it was never offered to any publisher at that time because historical fiction built around a real personage was considered very passé in the late nineties; furthermore, the original draft of the novel read a bit like `faction` – here was a historian sitting gingerly on the fence, afraid to jump off! So I put it in a drawer and forgot about it for several years.

By 2005, however, fictional trends had moved on, and I judged that the time was right to resurrect my project. I rewrote it entirely, moving from the third person past tense to the first person present tense, and halved the number of narrators, of which there had originally been sixteen. No one was more delighted than I when my revised novel – and another, yet to be written, on Katherine Howard – were commissioned by Hutchinson. I could not have asked for a more professional team to back me.

When Innocent Traitor hit the shelves in April 2006, a long-standing dream finally came true for me, but I must hasten to say that, although I am very excited about becoming a published novelist, I remain equally enthusiastic about my non-fiction books, of which I have two left on my current contract. The first is a biography of Katherine Swynford, the mistress and later wife of John of Gaunt, which I am writing now, and which is due for publication in 2007; and the second will hopefully be a book entitled The Lady in the Tower, which will tell the story of Anne Boleyn`s last seventeen days between her arrest and execution. Before I start researching that, however, I will be writing a novel on Katherine Howard, which will be another tragic Tudor tale, but with a very different heroine from Lady Jane Grey.

For me, it is a great privilege to be able to write both fiction and non-fiction books, and although my life is now very busy as a result, if those books bring pleasure to the people who read them, then I will account the effort more than worthwhile. As long as I don`t allow my novelistic flights of fancy to pervade my non-fiction……

ALISON WEIR ON INNOCENT TRAITOR, U.S.A., 2007

People often ask me why I chose to write a novel, Innocent Traitor, after publishing so many non-fiction history books. The truth is that I used to write historical novels as a hobby many years ago, and this one was written for fun too. Nine years back, while I was researching Eleanor of Aquitaine, I began wondering what it would be like to get inside the head of a historical character and use my imagination in telling their story, rather than being constrained by the strict disciplines of historical biography. Of course, once the idea was born, I had to pursue it! However, because of the limited leisure time available to me, I needed to choose a subject that would not result in a long book; I also wanted to write a dramatic story, and the tragic tale of Lady Jane Grey, England`s `Nine Days Queen`, seemed ideal – it had fascinated me since childhood.

I wrote the original draft in two months, called it Light After The Darkness, and sent it to my agent. But I hadn`t quite made it across the divide between history and fiction – I can see now that what I`d written could only be termed faction. Moreover, historical novels weren`t selling very well at that time, so I just put the manuscript away and forgot about it. Three years ago, I found it and rewrote the whole thing, then was absolutely delighted when it was accepted for publication.

In one respect, it was easier to write fiction than non-fiction, as I had already researched the subject and knew the story well, having covered Lady Jane`s life in The Children of Henry VIII. So the tale just flowed, tumbling easily out of my head. But I was also aware of the need to make this book sound very different from my non-fiction works, and to this end I chose to write in the first person and the present tense, because no history book could ever be written in that way.

I know that there is far greater scope for using one`s imagination in fiction, but as a historian, it was vital for me to make the novel as factually accurate as possible, and I used everything that could be inferred from historical sources to make my characters come alive. All the same, it was some while before I felt comfortable about coming down off the fence and letting my imagination rip…!

Overall, the whole experience was liberating. I loved the freedom of being so creative. Yet even historical fiction has its constraints. I was very conscious of how important it is to get the language spoken by the characters right, and spent a lot of time modifying original quotations – which I used wherever possible - so that they did not sound incongruous in a twenty-first century text. I also found that it is generally better to show the reader – through actions and conversations – what is happening, rather than relying on narrative skills to tell the story.

One problem I encountered was that, in nearly every respect, the historical Jane comes across at every stage of her life as much older than her years, and I feared that that portraying her in this way – which was essential if the book was to make sense - would stretch my readers` credibility to the limit. So I had others talk about her precocity and her formidable intelligence, and tried to show that in Tudor England, children were treated as miniature adults and expected to behave accordingly.

I`m aware too that some passages in the book may sound far-fetched, but those are the ones most likely to be based on fact! My editor suggested I omit a certain passage because it sounded `too contrived`, whereupon I pointed out that many historians also once thought it too contrived, but that the story came from a reliable source and is now accepted as fact by most scholars. The episode in question was that in which the warrant for Queen Katherine Parr`s arrest was fortuitously dropped in a corridor and found by one of her servants, who hastened to warn her.

For me, and I suspect for many other people, the Tudor period is perennially fascinating because of its dramatic events and outstanding personalities, and also because it is the first period in English history for which we have primary sources that reveal intimate and insightful details of the public and private lives of prominent figures. There is so much human interest to captivate the imagination, so many towering and colourful personalities, triumphs and tragedies, myths and mysteries, all played out against the magnificent backdrop of the greatest court ever seen in England, or the grimmer setting of the Tower of London, the cosy splendour of country houses and the teeming bustle of Tudor London. You couldn`t make it up!

The story of Lady Jane Grey is both compelling and poignant. I`ve always found her an intriguing character, for she was not always a sympathetic heroine, but a feisty and dogmatic teenager who could be uncomfortably candid, outspoken and uncompromising. I wanted the challenge of writing about her in such a way as to excite my readers` compassion, rather than having them pity her only on account of her youth and her being used as the tool of ambitious men. But Jane, of course, proved not to be the meek little thing that they had envisaged. She defied the conventions of a male-dominated age because she was exceptionally intelligent and a strong character – the perfect Tudor heroine for the modern era.

Furthermore, both Jane and her contemporaries confronted issues that have relevance for us today. We can contrast the religious fundamentalism of the Tudor age with that which is becoming alarmingly apparent in our own society in the wake of 9/11. In both cases, we see people who are prepared to die horribly for their beliefs, and those who display a lack of tolerance towards the beliefs of others. And because of our own experience of terrorism, we can perhaps understand the Tudor mind better. In many other ways, though, the past is indeed another country, and issues such as arranged marriages, family relationships, sexual behaviour, and child abuse – of which Jane was a victim – were looked upon very differently. All of these feature in the novel and have often prompted startled reactions from readers in the UK.

Will there be another novel? Indeed there will, although its subject is still under discussion. And I am continuing to write non-fiction books: I`ve just completed a biography of Katherine Swynford, John of Gaunt`s scandalous mistress and later Duchess, who was the ancestress of every British monarch since 1461 and of five US Presidents; and I am shortly to embark on an account of Anne Boleyn`s last days in the Tower of London. I must say I feel very privileged to be publishing both fiction and non-fiction. And I am very much looking forward to touring the US in March, and to meeting the readers who have made it all possible.

STORY BEHIND THE STORY: FICTION TO THE FORE

Booklist, USA, 2007

Ppular British historian Alison Weir is the author of several books about early English and Scottish royal history, including The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1992), The Princes in the Tower (1994), and Mary Queen of Scot, and the Murder of Lord Darnley (2003). Weir's first foray into fiction - not surprisingly a historical novel - is also drawn from the annals of royal history, specifically the Tudor era, which, as Weir avers in a conversation with Booklist, maintains its allure for contemporary readers because of the "colourful characters' who populated that time period's upper echelons of society. She finds those times so dramatic and exciting that a writer "couldn't make it up". One interesting fact that came up in our conversation: she has been writing fiction in her "spare time" for about 40 years. She wrote Innocent Traitor as an exercise while researching a non-fiction book on Eleanor of Aquitaine. Its appearance represents the first time she has attempted to publish her fiction. She had put the manuscript away because her agent called it "faction" and suggested Weir was "sitting on the fence" between non-fiction and fiction, and that to pursue fiction writing she would need to "take off [her] historian's hat".

The life of Lady Jane Grey attracted her interest because Jane "had the most dramatic and tragic story", which offered Weir "many opportunities for dramatisation". According to Weir, the UK is undergoing a renewed interest in historical fiction (concurrent with a renaissance in the US). In light of that trend, she retrieved the manuscript of her Lady Jane Grey novel from her drawer and rewrote it; it became a best-seller in Britain.

In an author's note at the end of the novel, Weir explains that as part of her fiction technique, she "tried to penetrate the minds of (her) characters". She insists that being allowed to do so proved "liberating", since it is a freedom that the non-fiction writer is seldom able to realise. She says she discovered that the basic difference between writing fiction and non-fiction is that the historian "can't allow any leaps of imagination", but the fiction writer may indeed fill in gaps with exactly that - one's imagination. She found that writing non-fiction is not as difficult as fiction, because in composing a biography the author generally follows straight chronology, which imposes its own structure, whereas the creation of a novel can offer the writer 20 different ways of telling the story, providing "a bit of a minefield" in deciding on the best approach. And, adding to the difficulty, historical fiction presents a problem of language; characters must "sound convincing and . . . of the period", she says, but not so archaic as to be incomprehensible to the modern reader. She relates the sad tale of Jane Grey in alternating first-person voices; she pared the original 16 voices down to 8 to best ensure that all characters sounded like individuals; she ultimately decided to have them speak in a "hybrid" of old and new language.

Weii reveals that her new novel, now in the works, is about Catherine Howard, the fifth of Henry VIUs six wives, who, like Lady jane Grey, lost her head - literally - at a tender age. The subject of the new novel is an obvious choice, for Weir admits that Henry's wives have always fascinated her.

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, U.S.A., 2007

Question: After ten enormously popular and critically acclaimed non-fiction books, what inspired you to make the jump to fiction with Innocent Traitor?

A: I've been writing historical novels for fun since the 1960s, and this one was no exception. I first wrote it eight years ago, while I was researching Eleanor of Aquitaine. It was then called Light After The Darkness, and was more "faction" than fiction. Historical novels weren't selling very well at that time, so I just put the manuscript away when I'd finished it. I rewrote the whole thing a couple of years ago and was delighted when it was accepted for publication.

Q: Did your experience as a non-fiction writer and historian make it easier to write fiction, or did you have to unlearn or set aside certain habits of mind and composition in order to write the novel?

A: It was easier to write fiction from the point of view of having seriously researched the subject and knowing the story well. But I was aware of the need to make this book sound very different from my non-fiction works, and to this end I chose to write in the first person and the present tense, because no history book could ever be written in that way. As a historian, it was vital for me to make the novel as factually accurate as possible, and I used everything that could be inferred from historical sources to make my characters come alive. Yet it was some while before I felt comfortable about coming down off the fence and letting my imagination rip!

Q: It must have felt liberating to be able to do away with footnotes for once! But fiction, especially historical fiction, has its own constraints, and I wonder if you found yourself bumping up against them.

A: The whole experience was liberating, not just being able to do away with footnotes. I loved the freedom of being so creative. Yet it's true that writing historical fiction does have its constraints. I was very aware that it is important to get the language spoken by the characters right, and spent a lot of time modifying original quotations—which I used wherever possible—so that they did not sound incongruous in a 21st century text. I also found that it is generally better to show the reader—through actions and conversations—what is happening, rather than relying on narrative skills to tell the story. One problem I encountered was that, in every respect, the historical Jane comes across at every stage of her life as much older than her years, and I feared that portraying her in this way—which was essential if the book was to make sense—would stretch my readers' credulity to the limit. So I had others talk about her precocity and her formidable intelligence, and endeavoured to show that in Tudor England, children were treated as miniature adults and expected to behave accordingly.

Q: In your author's note, you write: "Some parts of the book may seem far-fetched: they are the parts most likely to be based on fact." This bears out the old adage of truth being stranger than fiction. Were there facts that you felt you had to leave out because they would have seemed too far-fetched?

A: I'd never leave out substantiated facts just because they sound far-fetched! My editor suggested I omit a certain passage because it sounded "too contrived," whereupon I pointed out that many historians also used to think it too contrived, but that the story came from a reliable source and is now accepted as fact by most scholars. The passage in question was the one in which the warrant for Katherine Parr's arrest was fortuitously dropped in a corridor and found by one of her servants, who hastened to warn her.

Q: What makes the Tudor period of English history so perennially fascinating to you and to so many readers?

A: For me, and I suspect for many other people, the Tudor period is perennially fascinating because of its dramatic events and outstanding personalities, and also because it's the first period in English history for which we have primary sources that reveal intimate and insightful details of the public and private lives of prominent figures. There is so much human interest to captivate the imagination, a wealth of triumphs and tragedies, myths and mysteries, all played out against the magnificent backdrop of the greatest court ever seen in England, the grimmer setting of the Tower of London, the cosy splendour of country houses, or the teeming bustle of Tudor London. You couldn't make it up!

Q: Why did you choose the story of Lady Jane Grey as your subject?

A: Because I knew it well, I was aware that it had all the elements of a compelling and poignant tale, and I needed a story that was not too long. Above all, I've always found Jane an intriguing character, for she was not always a sympathetic heroine, but a feisty and dogmatic teenager who could be uncomfortably candid, outspoken, and uncompromising. I wanted the challenge of writing about her in such a way as to excite my readers' compassion, rather than having them pity her only on account of her youth and her being used as the tool of ambitious men.

Q: One of the most shocking things to a modern reader in your novel will surely be the extent to which women are little more than another type of property owned by often-brutal men. How, in this environment, could a woman be permitted to ascend to the English throne? Is that a quirk of history, or were there political reasons behind it?

A: There were political reasons behind the Duke of Northumberland deciding to place a woman on the throne, regardless of the perceived deficiencies of her sex. First and foremost, he wanted to remain in power, and he could only do that if, after the death of Edward VI, England was ruled by someone malleable who would bow to his tutelage. Jane was the only member of the royal House who was suitable for his purpose, so he married her to his son, and thus bound her to obedience to her husband, who would be Northumberland's tool. But Jane, of course, proved not to be the meek little thing that the Duke had envisaged…

Q: Yet despite the patriarchal culture, strong women could and did emerge from it, women like Jane and her cousin, Elizabeth. What accounts for that, do you think? Was it that these women were truly exceptional, or were other factors at work?

A: I believe that these queens rose above the constraints of a male-dominated age simply because they were exceptional, formidably intelligent and talented women, and also because their royal birth ensured their entrance to the political stage.

Q: Does the history of Tudor England have any relevance to what is going on politically and culturally in England and America today?

A: One could always contrast the religious fundamentalism of the Tudor age with that which is becoming alarmingly apparent in our own society in the wake of 9/11. In both cases, we see people who are prepared to die horribly for their beliefs, and who display a lack of tolerance toward the beliefs of others. And because of our own experience of terrorism, we can perhaps understand the Tudor mind better. In other ways, though, the past is indeed another country.

Q: I was intrigued by your characterisation of Henry VIII. He comes across as a much more likable figure than I would have imagined.

A: I was trying to portray Henry VIII as Jane would have seen him on this occasion, and for this I relied on the many descriptions we have of him as a sociable, affable, and witty man who was concerned to put others at their ease. He was not always the monster of popular caricature, nor the buffoon played by Charles Laughton!

Q: Will you be writing more novels?

A: Yes, I’m pleased to say that I have just completed my second novel, about which I’m extremely excited. It is about the early life of Queen Elizabeth I—a perilous, fascinating period when her path to the thone and her very survival were fraught with danger. Margaret Irwin aside, surprisingly little attention has been paid by writers of fiction to these years before Elizabeth became queen at the age of twenty-five, and I’ve found that it’s an especially rich subject for a novel.

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, U.S.A., 2007

1. As a first time novelist and noted historian, what attracted you to Lady Jane Grey’s story?

It was dramatic and poignant – ideal for fiction. I`d always been fascinated by it. And as I had limited time – I was researching Eleanor of Aquitaine when I first wrote this novel, back in 1998 - it was short.

2. Jane is witness to history at a most fascinating period, notably the reign of Henry VIII, his frantic pursuit of a male heir, discarded wives and an increasingly erratic temperament. Given the nature of the Tudor court, how was Jane’s young life determined by the times in which she lived?

In every way. She grew up bound by the formal manners of her day and was constrained to absolute obedience to her parents and to those of higher rank. As a female of the blood royal in a male-dominated age, she was powerless against those who schemed to use her for their own ends.

3. Jane’s mother, the Marchioness of Dorset is a cold and calculating woman, disappointed at not bearing a son and a harsh taskmaster to her daughter. How does her mother’s marked lack of affection form Jane’s character and the girl’s love of learning?

Jane`s love of learning is at least in part a means of seeking refuge from her mother`s harshness. The lack of maternal affection is to a large degree compensated for by the love of Jane`s nurse, Mrs Ellen, who is a more constant presence in her life, but her mother is all-powerful, and there is perhaps something of her in Jane, who is eventually driven to rebel against the Marchioness`s harsh rule.

4. Is Jane’s rigorous education beyond the norm for girls of her position and bloodline? If so, why did her parents encourage such an advanced education?

Until the sixteenth century, noble English girls were rarely well-educated. Sir Thomas More broke the mould by affording his daughters a classical education, and was emulated by Henry VIII and Katherine of Aragon, who provided a similar curriculum for their daughter, the future Mary I. These examples proved that an educated woman could also be a virtuous woman, and they set a trend. Henry VIII`s younger daughter, Elizabeth (I) was rigorously educated, as were various girls from noble families attached to the court, which was a centre of culture and learning. Thus, wishing to follow these examples, and aiming to marry their daughter to Henry`s heir, Prince Edward, Jane`s parents ensured that she too was educated as befitted a Renaissance princess and future queen.

5. Raised by proponents of the Reformed Church, Jane has little tolerance for those who believe in the Catholic faith, including Mary, daughter of Katherine of Aragon. Can you explain the paranoia regarding religion that permeates the court and the fear of an accusation of heresy?

In Tudor England, religious opinions were absolute and polarized, and any deviation from the officially sanctioned faith was regarded as heresy and punished, usually by burning at the stake. When Henry VIII broke away from Rome in the 1530s and declared himself Supreme Head of the Church of England, his church remained Catholic; therefore he burned Protestants for heresy and Catholics for persisting in acknowledging the Pope as head of the Church. Under his successor, Edward VI (1547-53), who had been educated by religious reformers who were closet Protestants, England turned Protestant, and the Catholic faith was outlawed. When Mary I succeeded in 1553, England was received back into obedience to Rome and Catholicism was restored as the official faith of the land. Mary, a fanatical Catholic, revived the heresy laws and burned 300 Protestants, earning herself the nickname `Bloody Mary`. When Elizabeth I succeeded in 1558, England reverted to Protestantism and the Anglican Church was founded, with Elizabeth as its Supreme Governor. It was an age of religious fundamentalism, in which religion played a major part in people`s lives, and the question of the correct means to salvation was literally the burning issue of the day. In this context, it is easier to understand why Edward VI and Northumberland schemed to place the Protestant Lady Jane Grey on the throne.

6. Jane witnesses a frightening episode when Katherine Parr is confronted with a scroll that accuses her of heresy, actually signed by the king. How does this unfolding drama affect Jane and her sense of security in the court? Are her religious beliefs not the same as Katherine Parr?

Yes, Jane`s religious beliefs are the same as Katherine Parr`s. Fear of what might happen to Katherine – in the light of the burning she has just witnessed in Smithfield – must have rocked Jane`s world and made her feel very insecure indeed, given that Katherine had been so kind to her and had facilitated her escape from her abusive parents.

7. What is the line of succession after Edward VI according to Hnery VIII’s will? As Henry’s niece, would the Marchioness have a legitimate claim, either for herself or her daughter?

According to the Act of Sucession of 1544, and Henry VIII`s Will of 1546 (which held no force in law and was not binding upon his successor), the order of succession was as follows: Edward and his heirs; then Mary and her heirs; then Elizabeth and her heirs; then the heirs of Henry`s younger sister, Mary Tudor, Duchess of Suffolk. In 1553, these were Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk, then her daughter, Lady Jane Grey. It is not clear why Frances relinquished her claim in favour of her daughter.

8. Thomas Seymour and the widowed Katherine Parr concoct a plan to marry Jane to Edward VI, hopefully cementing Seymour’s position with the new king at the same time. Would such a marriage be feasible? Why doesn’t the plan succeed?

Such a marriage would certainly have been feasible, and even desirable, but it was neither on Henry VIII`s agenda nor Edward VI`s. Henry wanted to marry Edward to Mary, Queen of Scots, and so unite England and Scotland under Tudor rule. Edward, in turn, desired to carry out his father`s wishes, but Mary was secretly sent to France, where she was betrothed to the Dauphin. Edward and his advisers then planned a marriage with a French princess, Elisabeth of Valois. Thomas Seymour had far less influence at court than he led others to believe. He thought that by suborning the young King by gifts of money, he could gain his confidence, but that plan misfired disastrously. For all these reasons, his plot to marry Edward to Jane was doomed to failure from the first.

9. As an historian, what do you make of the persistent rumor that Elizabeth had a child by Thomas Seymour?

As a historian, I would discount it. The midwife on whose tale this assertion is based could not even identify the young woman to whom she was taken in secret to attend in labour. Apart from the fact that Elizabeth was ill that summer – and she was frequently prostrated with illness as a teenager – there is nothing else apart from malicious rumour to suggest that she had a child by Seymour. As a novelist, however, I might think differently!

10. When living with Katherine Parr after Henry’s death, Jane comes into contact with Henry’s worldly daughter, Elizabeth. Does Elizabeth’s sophisticated world view alter Jane’s perception of court life? If so, in what way?

I don`t think Elizabeth influenced Jane very much in this way. After all, they were not at court during this period, just living privately with the Queen Dowager. Probably Jane would have looked up to and admired Elizabeth, who was four years older.

11. When John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, becomes the new Lord Protector of Edward VI, Jane finds herself once more in the crosshairs of ambition. Does she have any options in the matter of her future marriage or is she, once again, the helpless pawn of her parents? What are the inherent dangers in the plan? Please explain.

Warwick – soon to be created Duke of Northumberland – was never Lord Protector, but remained Lord President of the Council. Whatever his title, he was still the most powerful man in England. Against his might, and the injunctions of her parents, Jane was powerless. She protested in vain against her marriage, and unsuccessfully did her best to refuse the crown. Northumberland and her parents must have known the dangers to which they were exposing themselves and Jane. The device to change the succession was illegal (it takes an Act of Parliament to repeal an existing Act of Parliament), so Mary remained the rightful heir, and anyone else accepting the crown or plotting to put a pretender on the throne was guilty of high treason. But the stakes were high, and everyone underestimated to extent of popular support for Mary.

12. Jane avidly pursues knowledge for its own sake, language, the classics, philosophy and theology. While studying provides an escape from her reality (“I am so unhappy that I think myself in Hell.”). Other than for its own sake, is this knowledge ultimately of any value in her future?

In the Renaissance period, it would have been of value to any ruler to be rigorously educated. Courts were repositories of culture, and a monarch or consort needed to be able to converse knowledgeably with the scholars and artists seeking his or her patronage. He/she also needed a grasp of the languages required for successful international diplomacy, and an understanding of theology in an age of religious controversy. So if Jane were to marry the King of England, a classical education would be a distinct advantage. Even if she married a mere nobleman, it would serve her well when it came to interacting at court on an intellectual level, and in educating her children. And, of course, there was a certain personal fulfillment in loving learning for its own sake.

13. After all the years of giving in to her parents’ demands, Jane finally rebels when presented with the crown by Edward’s own order of succession. How does her immediate refusal affect Dudley and her parents?

Her refusal can have prolonged the proceedings for only a matter of minutes, but one can imagine how Northumberland and her parents felt about it, as they envisaged their carefully laid plans being wrecked. For Northumberland, there was the prospect of losing his best candidate for the throne, one who was married to his son, and by whom he hoped to found a royal Dudley line. Without her, he could not hope to remain the power behind that throne. For Frances, there is the prospect that she herself might have to step into the breach and take the crown. And for them all, there is the knowledge that their plans would be irrevocably weakened by Jane`s rejection of the throne, and that they ran a higher risk of being accused of treason. For it had taken a lot of manoeuvring on Northumberland`s part to get the lords and judges to accept Jane`s claim, and her refusal might lose him valuable support.

14. What higher motive causes Jane to change her mind and agree to accept the crown? Is this decision in her best interests or is she simply seduced by an opportunity to protect the citizens from the heresy of Catholicism?

By Jane`s own account, she prayed to God for guidance, but received no reply. This suggested strongly to her that her duty lay clear: she must obey her parents. And in doing their bidding, of course, she would be the instrument through which the kingdom would be saved from Catholicism. This must have been a powerful factor in her decision reluctantly to accept the crown. But by her own admission also, she knew she was on shaky ground legally.

15. Does Jane take the threat of Mary and her gathering an army seriously or does she believe her advisors that Mary can be neutralized? What is the reality of the situation?

The reality is that people were flocking to Mary`s banner from all over England. Northumberland had vastly overestimated his own support, and during the nine days of Jane`s reign, his fellow councillors were steadily abandoning him. Jane was apparently not taken fully into the council`s confidemce, but she seems to have understood the seriousness of the situation, for when Northumberland chose her father to lead a force against Mary, Jane insisted that he himself go instead. She must have realised that her father could only compound his treason by being taken in open rebellion against the rightful Queen, which was what in fact happened to Northumberland.

16. Jane’s new husband, the insensitive Guilford Dudley assumes he will be made king and rule the country beside his wife. Once again, Jane rebels. In this instance, can she prevail?

Jane can only prevail against Guildford`s demands until the matter is laid before Parliament, a parliament that – had things gone the way Nortthumberland planned – would certainly have done his bidding.

17. In perhaps the most ironic event of Jane’s young life, it is her devotion to religion that stands in the way of a freedom. Can you speak to the terrible choice Jane faces and why she is unable to do the one thing that can save her life?

We`re back to this issue of religious fundamentalism. Jane believed that the Protestant faith was the only means of attaining eternal life; that is why she was so distressed at bidding farewell to Abbot Feckenham on the scaffold, because she was convinced that he, as a Catholic, was destined for Hell, and that they would never meet again in the hereafter. For her, dying a Protestant is therefore the only means of attaining salvation and Heaven; there is no choice in the matter.

18. Mary is faced with a conundrum as well: fear that the Protestants will rally around Jane, given the opportunity, if she is freed from the tower. Both these figures are caught by the political events that restrict their choices. Given different circumstances, might they be sympathetic to one another? Are they not similar in some ways?

There is no doubt that Mary was sympathetic towards Jane, on account of her youth and the fact that she had been the helpless tool of others. She did everything she could to save her. But Jane was never very sympathetic towards Mary, even though she acknowledged her right to the crown. Jane was openly disapproving of Mary`s religion, and made no secret of that when she was in the Tower, which seems a rash thing to do in the circumstances. Had she lived, or even ruled, she would probably been as fanatical a Protestant as Mary was a Catholic. In that respect, the two are similar. And, of course, both are the victims of circumstances beyond their control.

19. How would you describe Lady Jane’s place in history?

Not too significant. She was little known, she did not attract a following and she was queen in name only for just nine days. She left no legacy, unless one counts the crown`s continuing distrust of members of her family, who were too near in blood for comfort. Her story merely illustrates the power struggles of the day, which were informed by religion, personal ambition and a desire for political control.

20. Throughout the novel, I am constantly struck by Jane’s youth; she is only sixteen when crowned queen. Is it not troubling that such a figure can be manipulated from her childhood, not even attaining adulthood before she falls victim to the machinations of those around her?

It is very troubling indeed, and it demonstrates how far the ruthless operators of the day were prepared to go to achieve their ambitions – they did not scruple to use one so young and innocent to further their dangerous plans. Of course, in Tudor eyes, Jane was virtually a woman. There was no concept of childhood as a separate phase of development. Children were miniature adults who had to be civilized as soon as possible. Girls could marry and cohabit at twelve, boys at fourteen; boys as young as eleven went to war. So a girl of fifteen (sixteen, according to very recent research) sitting on the throne was not thought so unusual, for several monarchs had succeeded as infants. Yet a royal minority often brought with it power struggles and intrigues, as had been seen repeatedly in Scotland for well over a century. Unsurprisingly, there was an old adage, Woe to thee, O land, when thy king is a child. How apposite in Jane`s case.

21. Lady Jane Grey’s progression to queen, if only for nine days, is a convoluted path at best, the pawn of the ambition of others. How does her life define the role of women of that era, especially those with royal blood?

Her experience demonstrates how constrained royal women were to obey and serve their parents, their menfolk and their rulers. A woman in that age knew little autonomy, and – as Jane`s story shows – could be easily overruled.

22. How was writing fiction different for you? What was most challenging? Most rewarding?

Writing fiction was particularly liberating; at last, I could let my imagination rip. I could get inside the heads of characters with whom I had long been familiar, and actually be them. That was the most rewarding part. The most challenging aspect was getting the language right. Having studied Tudor sources over several decades, I knew a lot of idioms, and where there was contemporary speech, I used it, sometimes out of context, taking care to modernize it slightly so that it would not appear incongruous in a twenty-first-century text. But you can never please everyone – some reviewers said I`d got it just right, others complained about anachronisms. To me, it felt right, and I had to make it accessible to the widest-possible audience, so I felt that the deliberate use of a few anachronisms was permissible.

23. Now that you have written a novel, have you plans for another? If so, can you share anything about your next project?

I`m writing a second novel at the moment. Entitled The Lady Elizabeth, it is about the early life of Elizabeth I, up to her accession. And I`m planning to make it very controversial! More than that, I am not prepared to say! Wait and see…

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, U.K., 2007

1. You are best known for your very successful non-fiction writing. What inspired you to write novels?

I wanted to free myself from the strict disciplines of historical interpretation, get inside the heads of my characters and imagine what it was like to actually be them. I also wanted the freedom to fill in those frustrating gaps where evidence is missing. Above all, I wanted to explore characters and relationships in more vivid detail, and write dialogue.

2. In all your research, is there one character from history, which you find particularly intriguing? Or unpleasant?

I would have to say that Anne Boleyn intrigues me most. My interest in history began with her, and it keeps coming back to her! I must add, though, that having researched her life in detail over the years, I don`t find her as romantic a character as I once did, and I don`t think she was particularly likeable. The most unpleasant character? Leaving aside all the mass murderers and dictators, the most unpleasant character I have researched has to be Lord Darnley, the second husband of Mary, Queen of Scots. Apart from his youth - he was twenty when he was murdered - he had no redeeming features. He was callous and ruthless, and I think that if I had been married to him, I might well have murdered him!

3. What was it about the story of Lady Jane Grey that inspired you to write a novel about her life?

It was dramatic and poignant – ideal for fiction. I`d always been fascinated by it. You couldn`t make it up! And as I had limited time – I was researching Eleanor of Aquitaine when I first wrote this novel, back in 1998 - it was short.

1. What sources were particularly helpful when writing Innocent Traitor?

Numerous sources, all contemporary - far too many to list here! I was fortunate that, when I came to write Innocent Traitor, I had already researched Lady Jane`s life for my non-fiction book Children of England: The Heirs of King Henry VIII, so I knew the story very well. Wherever possible I used Jane`s own words, taken mainly from her account of events and her letters.

2. While in the Tower of London, Lady Jane Grey wrote ‘If my Faults deserve punishment, my youth at least, and my imprudence, were worth of excuse. God and posterity will show be favour’. How much do you think Lady Jane Grey’s situation was caused by her imprudence and how much was it the consequence of other people’s greed?

I don`t think that Jane was imprudent as such in accepting the crown: I believe that she had no real choice in the matter, that she was the pawn of ambitious and greedy operators who had their own political and religious agenda, and that she was more or less aware of that. Furthermore, I think she felt that she was doing God`s will in obeying her parents, and that in so doing, she was being called to a position wherein she would have the power to preserve what she believed to be the true faith - Protestantism. It is clear, however, that she did not want the crown and that she remained troubled about not being rightfully entitled to it.

3. Primogeniture is a major issue was a major issue at the time. How would Lady Jane’s life have been altered had she been born a boy?

I think her home life would have been happier if she had been a boy, as her parents had desperately wanted a son to continue the family name, and resented the fact that Jane was a girl. I also believe that a male claimant of the House of Suffolk would have been of even greater use to Northumberland than a female one, and far more of a threat to Mary Tudor than Jane was. Northumberland could have married him to one of his daughters to cement the alliance with the Suffolks and, given the prejudice against women rulers, and the fact that all the politicians involved in the coup were men, the plot to displace Mary might well have had more chance of success. Had Jane been a boy, we might yet have a Grey dynasty on the throne today.

4. What are your favourite books?

I read a wide variety of books, but as I spend much of my life poring over historical sources, I like to read page-turning novels in my leisure time. My all-time favourite novels are Anya Seton`s inspirational Katherine, about Katherine Swynford, the subject of my latest biography; and Norah Lofts` trilogy, The Town House, The House At Old Vine and The House At Sunset - it`s the history of England over six centuries told through insights into the generations of inhabitants of a Suffolk house - and a monumental achievement. Historical novels don`t come much better than this!

FROM FACT TO FICTION

Interview with Patrick Bishop, Saul David, Harry Sidebottom and Alison Weir

BBC HISTORY MAGAZINE, Vol. 9, No. 10, October 2008

Why have you chosen to write historical fiction?

Patrick Bishop: I love novels from the period of the Second World War and I thought I would write my own.

I was inspired by a particular story of an SAS operation in northern France just after the Normandy invasion, so I made that the climax of my book.

Saul David: Having got to a certain stage as a historian, I felt that as a break from the day job it would be great to tinker around with history in a way I’m not normally allowed to. With straight history everything, even the conjecture and supposition, has to be properly sourced – based on what is likely, rather than what we think instinctively probably happened. In other words, writing fiction is a great relief.

Alison Weir: It goes back to 1998 when I was researching a biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine. With medieval biographies like that, you’re dealing with fragments of evidence and you have to piece them together like a jigsaw puzzle. I thought, “Wouldn’t it be great to have the freedom a novelist has to be able to fill in the gaps and speculate on what really happened behind the scenes.”

That’s why I decided to write a novel. As I didn’t have much leisure time, I chose Lady Jane Grey because she was a subject I had already researched. I wrote my novel in two months, then showed it to my agent, who said that it was a riveting story but read like `faction`. He told me I had to get off the fence, stop being a historian and start being a novelist. But I`d run out of time, so I put the manuscript away in a drawer and forgot about it. In 2003, I rewrote it in a different form, and sent it back to my agent, who then sold it to Hutchinson.

Harry Sidebottom: It seemed to me a natural step in that it combined two lifelong passions, one being classical history and the other being fiction. Writing fiction has enabled me to do things that straight history doesn’t, such as inventing characters and dialogue and writing descriptive passages. It is also incredibly good fun.

How much research goes into producing a historical novel?

SD: I was quite lucky in that I’d written a history book about the Zulu Wars so I had a lot of solid factual information at my fingertips. What I didn’t have was the colour. For example, what did the inside of the War Office look like in 1879? Or, what would a journey from Britain to South Africa have been like in 1878–79? All of that kind of information I had to find in much greater detail than I would ever have had to for a history book.

HS: I would say that it has taken just as much research and just as much time as my first straight history book. It leads you into areas that your work as a professional scholar doesn’t, in that to write the novel I had to research things like food, clothes and aspects of social history that I had never had to think about before.

Is factual accuracy still important for historical fiction?

PB: Yes, because if something is wildly implausible then the reader loses faith in you. At the same time you can take it too far. At various points you have to remind yourself you are writing a novel and you do have to allow your imagination to override the facts at various points.

AW: I think it is very important. I’ve done many events promoting my novel, and I know that the readers really care that what they are reading is the truth. A lot of people rely on historical novels to learn about history, so I believe that, where the evidence exists, the author should use it. You’re not bound by the same constraints a historian has to abide by, but whatever you write has to be credible in the context of what is known.

Does your background as a historian give you an advantage in this sense over other historical novelists?

HS: I bloody well hope so! I think it may have been Ian McEwan who said recently that you don’t need to be an expert in a period to write a historical novel about it. I don’t really think that

is true because people who became experts in their field wrote far superior historical novels to those who didn’t. They also took the risk of allowing their characters to have different attitudes and values to modern people. I certainly think that is where a lot of historical fiction fails totally. It may get the externals right but it just falls flat by putting modern people in fancy dress.

Do you think historical fiction is a good way for people to get into history?

SD: Definitely. If it encourages someone to get into history seriously then I think that is fabulous. Let’s say someone reads my novel and they want to know more about the Zulu Wars and start reading history off the back of that or even watching TV programmes about it – that’s all grist to the mill as far as I’m concerned.

AW: That’s the way I got into history. When I was 14 my mother marched me into the library and told me to get a book out. So I did – I got my first adult novel, which was about Katherine of Aragon. It was a bit trashy but I devoured it in two days and had to rush off to the history books in my school library to find out what really happened. That sparked my passionate interest in history.

Who are your favourite historical novelists?

PB: One of my favourite authors is Joseph Roth who wrote a book called The Radetzky March, which is a brilliant evocation of the end of the Habsburg Empire. I also found the Second World War passages of Anthony Powell’s A Dance to the Music of Time to be extremely good. And of course Evelyn Waugh for his Swords of Honour trilogy.

SD: The lately departed George MacDonald Fraser who I actually interviewed the year before last for The Daily Telegraph. Part of the reason for interviewing him was that I’d written a book called Victoria’s Wars and my interest in that period was inspired by reading the Flashman novels. Apart from being a hugely talented writer he took his historical research very seriously. You can get an awful lot of very accurate history by reading MacDonald Fraser’s novels.

AW: Hilda Lewis, Nora Lofts and Anya Seton. We’re going back a few years; they’re all dead now, but some of their books were republished only last year. They wrote wonderful novels with great integrity, and when I recommend them to my historian friends who haven’t read them, they think they are wonderful too. It`s their style of writing and storytelling skills that make them my favourites, and the history is pretty sound.

HS: Mine are Patrick O’Brien, Mary Renault and the Irish writer JG Farrell. I like the fact that they allowed themselves to write slower-paced books that had light and shade. They weren’t just wham-bam explosion thrillers but novels where they could take their foot off the gas and put it back on.

Would you ever write a novel set outside the areas you specialise in as a historian?

PB: Yes, I’m planning to already and I’ve got several ideas up my sleeve. I was a war correspondent for many years and I hope one day to use the experiences I had in the Middle East and the Balkans in the form of a novel.

SD: Possibly. I’ve written a book called Military Blunders which jumps through the ages, so although I am a specialist in 19th-century military history, I have written about other areas. But I probably wouldn’t stray out of the 19th and 20th centuries to be honest. One of the problems with going too far back is that you really are lost for source material.

AW: Not really because I have this constraint of time. Innocent Traitor did quite well, so Hutchinson want more novels, but my other publishers, Jonathan Cape, also want me to go on writing history books, so I am very busy. This means I’m having to choose subjects I have researched already.

Or would you even consider writing a non-historical novel?

SD: I think that may be going one step too far. I don’t think I’ll ever call myself a novelist – I’ll always be a historian who writes novels. First and foremost my day job is to write history. But you never know. Ask me again in a couple

of years’ time because if my novels have been a great success there might be pressure on me to concentrate on

them more.

AW: Oh yes. I’m actually working on some ghost stories at the moment although it’s purely for personal pleasure. If I feel that they work then I might give them to other people to read and see what they think about them.

HS: I would love to write a novel set in the world of horse-racing that I grew up in. It would be like Dick Francis, except with a bit more swearing, drug-taking, explicit sex, violence and some real history as well!

The Execution of Lady Jane Grey by Paul Delaroche, 1833

Notes for a lecture at the National Gallery, London, 2010.

This is an extraordinary and powerful picture. Its impact is immediate. We know at once what is going to happen in the next few seconds.

Our eyes are drawn to the central figure of Lady Jane, almost luminous in her virginal white silk gown. Her hands, reaching out in panic, are those of a child. She is a sacrificial victim. The picture is capturing a moment of great drama, intensity and poignancy.

Immediately, we are asking questions. Who was Lady Jane Grey, and why was she facing death on the block? Clearly hers was a tragic and shocking story, and it is hardly surprising that, when this painting was exhibited at the Paris Salon of 1834, it caused a sensation.