Books

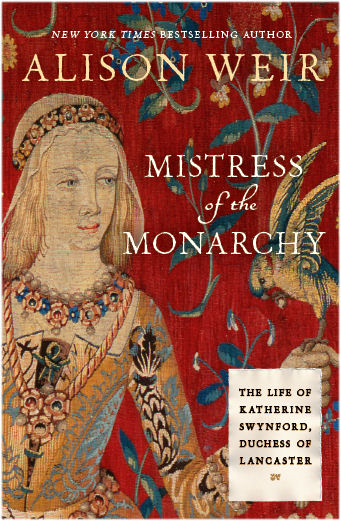

Katherine Swynford: The Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess/Mistress of the Monarchy: The Life of Katherine Swynford, Duchess of Lancaster (2007)

"It takes a biographer of immense learning, keen insight and sharp, decuctive powers to construct, from the few extant facts, not just a life of Katherine Swynford, but an entire romantic narrative not just inspired by Anya Seton's novel, Katherine, but far surpassing it in terms of sympathy and historical credibility. Weir's sound scholarship and storyteller's gift for rich, telling detail constantly engages and enthrals the reader." (The Times)

"Fast-paced, lively and boldly coloured, Weir's book gives us a vivid portrait." (The Sunday Times)

"Weir brings alive the brilliant beauty whose descendants would sit on the British throne." (Deirdre Donahue, U.S.A. Today)

"Weir is cautious and careful about her facts... Nevertheless, the story is an exciting one. Weir is an objective and enthusiastic storyteller, and brings not just Swynford, but all connected with her, to life." (Sunday Business Post)

"Weir combines high drama with high passion... A most remarkable woman in an equally remarkable book." (Scotland on Sunday)

"An above-excellent book that will have you reading and re-reading it." (The Bookfiend's Kingdom)

"Alison Weir steers a judicious line between fact and fiction. What is remarkable about Weir's entertaining tale is the fact it is spun from very little by way of contemporaneous records. Meticulous period research enables the author to weave a rich tale... Weir gives the lie to the idea that scholarship is dull." (The Sunday Express)

"For readers who like clear-cut, analytical research-based biography, Alison Weir is a fabulous historian who does her biography subject justice." (Curled up with a Good Book)

"Alison Weir has written a magnificent book that illustrates what historical research can achieve when done by the right person. There is a hard-nosed detective under the graceful stylist, and a bloodhound who leaves no scent unturned. Best of all, she has given us Katherine again, less girlish than Anya Seton's, but still able to reach down the centuries and make us fall in love with her once more." (LexisNexis)

"Weir is the gold standard for British royal biographies and her books are both well researched and outstandingly readable. [She] has produced another of her outstanding royal biographies. Read it and learn about history, without the boredom you'll find in so many history books." (Huntington News Network)

"With a practiced hand, royal biographer Weir carefully reconstructs a passionate historical love story." (Booklist)

"Weir’s well-researched, engrossing and perceptive biography gives a gutsy beauty her due while vividly describing the age of chivalry and its many players, including Katherine’s renowned brother-in-law, Geoffrey Chaucer." (Publishers Weekly)

"Bowled over by this tale of true love, Weir recaptures its glow in a fluid, artfully assembled narrative. Quite beguiling." (Kirkus Reviews)

"Meticulously researched... Weir does her usual excellent job of pulling together the information available... Weir's storytelling shines... For anyone interested in a real picture of this fascinating woman, this biography is not to be beaten." (Lea Valley Star)

"It is a very good read, very well written, well researched and gives an insight into the England of that time." (Liz Taylor, ibrarian, who chose Katherine Swynford as Lincolnshire Libraries' Book of the Month in April 2009)

"Weir takes the little information there is about the Duchess of Lancaster to reconstruct a medieval life in full... Weir creates an incredibly detailed account [and] never fails to convince. The gorgeous selection of illustrations add substance and pleasure to the enjoyment of this recreated life of a mysterious, inspiring woman." The Times Picayune, New Orleans)

Random House UK Newsletter, 2007, sent out to readers to coincide with publication.

I am delighted once more to be publishing an Alison Weir Newsletter in conjunction with my latest book, Katherine Swynford: The Story of John of Gaunt and His Scandalous Duchess. This book is very special to me, because in writing it I have fulfilled a long-standing ambition to tell Katherine's story, an ambition I have cherished for more decades than I care to remember. Its publication is no less than a dream come true.

Like many people, I first became fascinated by Katherine Swynford when I read Katherine, Anya Seton's famous novel about her, which was first published in 1954 and has not been out of print since, although the full, unabridged edition has only ever been available in America. As a fifteen-year-old, I was utterly captivated by that novel, and all these years later, it still inspires and moves me. It inspired me back then, too - I still have the rather amateur novels it prompted me to write - and it launched me on a quest to find out more about Katherine Swynford.

Never did I for a moment think that it would ever be possible to write a factual book about her. To begin with, I didn't become a published author until many years later. And even then, in the late Eighties, no publisher would have commissioned a biography of a relatively obscure medieval royal mistress, who left behind no quotes or letters for posterity. Indeed, she rated barely a passing mention or footnote in most history books. Only very recently, with the explosion of interest in women's histories, did such a biography become a viable prospect. I feel very privileged to be the author who has written it, and to have had the opportunity of researching the vivid tapestry of Katherine's life and discovering the truth about her - or coming as near to the truth as anyone now can ever get. It has been a thoroughly absorbing and enriching experience.

Mine is not the first factual book on Katherine. Last year, Jeannette Lucraft published an academic study that comprised a series of essays. My book, however, is the first full-scale biography. In fact, like my earlier works on mediaeval women, Eleanor of Aquitaine and Isabella, She Wolf of France, Queen of England, it is more a work of historical detection, because the evidence for Katherine's life is largely fragmentary or tantalisingly obscure, and nearly every aspect is controversial. The finished book reflects what I have been able to piece together or infer from contemporary records; surprisingly, a cohesive and ultimately moving story has emerged.

Nevertheless, nearly everything about Katherine Swynford is subject to debate: her origins, the important dates in her life, the children she bore, her character, what she looked like, and - above all - her relationship with one of the greatest princes of the Middle Ages.

She was undoubtedly beautiful and accomplished. The poet Geoffrey Chaucer was her brother-in-law. She lived through the Black Death, the Hundred Years' War and the Peasants' Revolt. She was acquainted with all the great personalities of fourteenth-century England. She wasn't English, but the daughter of a knight of Hainault (modern Belgium), and she was born around 1350. Most famously, she was for twenty-five years the mistress of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (1340-1399), the fourth son of King Edward III of England. During that period, she bore him four children, all surnamed Beaufort, and from them were descended the Royal Houses of York, Tudor, Stuart and every British sovereign since 1461. Thus Katherine Swynford is of key dynastic importance in the history of the British monarchy. Not only that, but five American presidents are descended from her.

Katherine was an extraordinary woman, but was she a whore and a witch, as the chroniclers claimed? Did she deserve to be the object of such calumny? Or was she an intelligent, literate and discreet woman who had a gift for dealing with people and who cared about her public image?

In my book, I have tried to answer those questions, and resolve all the other intriguing issues concerning Katherine; and in the process I have arrived at conclusions that surprised even me, for I had long believed Anya Seton's novel to be an authentic portrayal, based as it was on four years of conscientious research. But I learned a lot about that novel too, and my findings appear in an appendix, as do my reasons for not relying on it too greatly as a historical account. Given the enduring hold that this novel has exercised over the collective imagination of Katherine's many 'fans', it is my sincere belief and hope that this new biography will challenge long-held preconceptions about her and John of Gaunt.

My book focuses almost as much on John of Gaunt as it does on Katherine Swynford - hence its title. The Duke was a towering, charismatic figure who was himself the object of much unjustified vilification for many centuries. He was a chivalric knight, the virtual ruler of England for many years, a king in his own right, a man of honour, and a famous lover who married three times.

The late fourteenth century is a wonderfully colourful period, and the lives of John and Katherine were played out in the sumptuous but licentious courts of Edward III and Richard II, the fabled but ill-fated palace of the Savoy, the splendours of the Lancastrian castles, the poverty of Katherine's Lincolnshire manors, and the great cities of London and Lincoln. It is a vivid medieval pageant that builds to a poignant yet triumphant conclusion.

It is all too tempting to approach a subject like Katherine Swynford from a modern feminist viewpoint, and that raises wider issues about which I havw some firm opinions. How far should an historian go in taking such an approach? In my view, it would be inappropriate, because there was no such thing as feminism in Katherine's day, and the subject of a biography should always be studied and assessed within the social and cultural context of the age in which they lived. I think it is perfectly legitimate to stress aspects of their life or character that have relevance for us - and particularly for women - today, but these should not be allowed to supersede or belittle the things that were important to their contemporaries. We would not wish to be judged by medieval standards, so why should we judge someone like Katherine by modern standards?

Which brings me to another aspect of historical biography. Recently I took part in a debate with other historians at the University of Cambridge. We were discussing whether it was legitimate for a biographer to incorporate fictional details into their text, namely suppositions based on sound historical research. One author had written a battle scene with fictional embellishments, which were probably pretty spot-on, given how well she knew her subject; her argument was that it was acceptable to 'realise' such details, even though there was no historical evidence to substantiate them. I cannot agree. I think that every piece of information you put in a biography must be supported by contemporary evidence. Therefore you cannot say it was a fine day with clear blue skies unless you have a source to support that. When it comes to theories and inferences, you must present the evidence and make it clear how you have reached your conclusions. If the evidence just isn't there, you should say so.

It would be impossible to cite all the sources I use in my books, given that I have been researching many subjects for decades and that some passages are based on knowledge I have accumulated over the years. I always cite my main sources so that the reader knows where specific information and quotes come from, and I always give brief critiques of important sources, again so that the reader can assess their likely veracity or bias.

Over the coming months, I will be giving talks on Katherine Swynford at various locations around the country, and I am greatly looking forward to meeting many readers and fellow enthusiasts at these events. For details, please visit my website, www.alisonweir.org.uk. I know that a lot of people cherish an affectionate interest in Katherine - witness not only the websites and the thousands of hits you get if you type in her name on an internet search engine, but also the existence of a Katherine Swynford Society and the ripple of excitement I have detected at events every time I've announced that my next book would be about her. I lost count of the people who came up to me afterwards and said,'I read Katherine...'

Probably one of the most enjoyable aspects of my life as an author is meeting readers at events. Writing is a solitary occupation, one that I love, but it always gives me such a buzz to go out and meet people who share the same passion for history as I do. Seeing responsive and eager faces, eliciting laughter, sadness or shock, chatting with people afterwards - it's all a joy.

Having the new website is another way in which I can keep in touch with readers. You can email me direct from there - just go to the Contact page - and I will try to respond as soon as I can. Please bear with me - I may not always be able to reply at length, because my schedule is so busy, nor can I undertake any

research at a reader's request, or enter into a lengthy correspondence, again because of time constraints. Yet I do so enjoy hearing from you, and I always do my best to espond promptly to your messages or answer your queries. So please keep them coming!

WHAT'S NEXT - from the 2005 ALISON WEIR NEWSLETTER

Regular readers may be pleased to know that I have some exciting projects in preparation. The story in my next book is one I have wanted to write about for nearly forty years. It is one of the greatest love stories in English history, and the subject of one of the most loved of historical novels. My book, of course, is to be about the extraordinary love affair between Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.

Many people, to my certain knowledge, have been entranced by this tale after reading the famous novel, Katherine, by Anya Seton, which was first published in 1954, and then republished with its full text restored (in Britain, every edition had been abridged) in 2004 to mark the fiftieth anniversary of the book's first appearance. I first read Katherine in the late sixties, and was enthralled; and I was no less enthralled when I read it again, for the umpteenth time, last year. And I'm not the only one. Katherine was voted into the Top 100 in the BBC's 'The Big Read' in 2003, and its popularity is such that, on the sign by Katherine Swynford's tomb in Lincoln Cathedral, it says 'This is Katherine, of Anya Seton's popular historical book'.

The Cathedral Library holds annual Katherine Swynford Study Days that are regularly sold out. Look up Katherine Swynford on the internet, and you'll find thousands of entries: she is the subject of a number of websites and more than one discussion group. And at events, when I've been asked what my next project is, there is invariably a frisson of excitement in the audience when I say, 'Katherine Swynford'. Without fail, people will come up to me afterwards and say, 'I read Katherine...'

In its day, the novel was highly controversial because of its sympathetic portrayal of the adulterous lovers, which was considered shocking in the staid 1950s. Plans to film the novel with Charlton Heston and Susan Hayward were scuppered early on because Hollywood dared not portray Katherine and Gaunt, adulterous lovers for a quarter of a century, enjoying a happy ending.

Katherine is going to be a hard act to follow, but my book will of course be a work of non-fiction, for which I've gone back to the original sources of the period. When this book was commissioned, I pointed out that the evidence for Katherine's life was, to my knowledge, even more fragmentary than that for the lives of Eleanor of Aquitaine or Isabella of France. However, with my research almost completed, I now have two lever-arch files full of those fragments, and I also know that the story I have to tell will be somewhat different from that in Anya Seton's novel. Wonderful as that novel is, its author took considerable liberties with the historical facts in order to weave her fictional tale, and that is of course acceptable dramatic licence. But a historian has to work with the known facts, and in this case they raise more questions than they answer. What I can say at this stage is that my view of Katherine Swynford is not the one I had when I began my researches. I'm due to deliver my biography of her in the summer of 2006, and it will be published by Jonathan Cape in the autumn of 2007.

Speaking of fiction, I'm delighted to be able to say that Hutchinson will be publishing my first novel, Innocent Traitor, which tells the story of Lady Jane Grey, in April 2006. It will be followed later by a novel about Katherine Howard. Writing fiction is something I've wanted to do for a long time, but that does not mean to say that I am no longer interested in writing my non-fiction books. On the contrary, I'm thrilled to have the chance to work in both fields, and have some very exciting ideas for future non-fiction projects, which I hope to reveal in the next newsletter. This will mean that I'll be publishing a new non-fiction work one year, and a new novel the next, with the paperbacks appearing about a year after the hardbacks. I know I'm going to be busy, but I'm really looking forward to the challenge.

Above: Rejected U.K. (left and below) and U.S. (right) jacket designs.

ABOUT KATHERINE SWYNFORD by Alison Weir

• Everything about Katherine Swynford is controversial: her origins, the important dates in her life, the children she bore, her character, what she looked like, and—above all—her relationship with one of the greatest princes of the Middle Ages.

• She was undoubtedly beautiful and accomplished. The poet Geoffrey Chaucer was her brother-in-law. She lived through the Black Death, the Hundred Years’ War and the Peasants’ Revolt. She was acquainted with all the great personalities of fourteenth-century England. Five American presidents—George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George W. Bush—are descended from her, as are Princess Diana, Sir Winston Churchill and Alfred, Lord Tennyson. And she is the subject of Katherine by Anya Seton, one of the most enduringly popular novels of the 20th century.

• Katherine Swynford (c.1350-1403), the daughter of a knight of Hainault (modern Belgium), was for twenty-five years the mistress of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster (1340-1399), the fourth son of King Edward III of England.

• During that period, she bore him four children, all surnamed Beaufort. From them were descended the Royal Houses of York, Tudor and Stuart - in fact every British sovereign since 1461. Thus Katherine Swynford is of key dynastic importance in the history of the British monarchy.

• The love affair between John and Katherine provoked a massive scandal, for he was married to a beautiful young queen for most of its duration, while even greater scandal ensued when, defying tradition and flouting convention, he married Katherine in 1396.

• Was Katherine a whore and a witch, as the chroniclers claimed? Did she deserve to be the object of such calumny? Or was she an intelligent, literate and discreet woman who had a gift for dealing with people and who cared about her public image?

• In this book, Alison Weir has pieced together a wealth of tantalising fragments of information in her quest to discover as much as possible about the real Katherine Swynford. What has resulted from her extensive, often original, research, is the first proper full-length biography of this extraordinary woman, a biography that will challenge long-held preconceptions about Katherine and John of Gaunt.

• The book is also about John of Gaunt, a towering, charismatic figure who was also the object of much unjustified vilification for many centuries; he was a chivalric knight, the virtual ruler of England for many years, a king in his own right, a man of honour, and a famous lover who married three times.

• Set against a vivid backdrop that embraces the sumptuous but licentious courts of Edward III and Richard II, the fabled palace of the Savoy, the poverty of Katherine’s Lincolnshire manors, and the great cities of London and Lincoln, KATHERINE SWYNFORD is a colourful medieval

pageant that builds to a poignant yet triumphant conclusion.

To watch Alison Weir speaking about Katherine Swynford at Sandwich, go to:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xe52tzKyOm8

THE APPEAL OF MEDIEVAL BIOGRAPHY

Talk given by Alison Weir in September 2005 at a Biographers’ Club lunch at the Savile Club, London, in the presence of H.R.H. Princess Michael of Kent.

Since the age of fourteen I have been fascinated by the Middle Ages. Over the years that long-lost world has become strangely familiar to me, and yet I remain aware that, as far as the era between the Dark Ages and the Tudors is concerned, the past is definitely another country. Were we to be transported back in time, I have no doubt

we would find ourselves in totally alien territory; yet if there is one thing that the study of history has taught me, it is that human nature does not change. And it is people – the people of the distant past in whom I am interested.

I came to the study of the medieval period via an unconventional route, that of royal and aristocratic genealogy. In my naivete, I approached my early research confident in the belief that every item of information I was looking for would be recorded somewhere. It was some years before I realised how wrong I was.

As my research broadened and I learned more about the sources available, and discovered more about the lives of the individuals whose genealogical details I had plotted, the attraction of the medieval period increased immeasurably. I felt sometimes – I still do – that I was more at home in the Middle Ages than in my own century. Yet at the same time two things became clear.

First, that piecing together the life of any medieval subject is like undertaking detective work. Second, that there was a dearth of books about medieval women. Remember, this was the late 1960s and early 1970s, and most references in history books even to royal and aristocratic women were usually superficial, and often dismissive at best. Women were not important, either in the medieval mindset or – with a few notable exceptions – the minds of historians. Most books about royal women were by women, and were perceived as light, popular history; and a lot of information about women was relegated to footnotes.

Unfortunately – or fortunately, as it turned out – my chief area of interest was in the lives of long-dead queens and noblewomen. In the 1970s, having spent three years researching and writing the book that would later be published as The Six Wives of Henry VIII, I began a monumental research project on the lives of all the medieval English queens, from the Norman Conquest of 1066 to the late fifteenth century. This project took several years, and I have since used some of the research for a number of my books.

When I at last got into print in 1989, it was with Britain’s Royal Families, the product of twenty-two years of genealogical research. This was followed in 1991 by The Six Wives of Henry VIII. Around 1990 I put forward a proposal for a biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine, one of the towering female figures of the medieval period, but it was rejected on the grounds that a biography of a woman who had been dead for eight hundred years could not be written in the same way as a book of Henry VIII’s wives as there were too few quotes and surviving letters. It took eight years of resubmitting that proposal, a supportive literary agent, and the success of my biography of Elizabeth I (1998) before I finally got the go-ahead to write about Eleanor, and I’m still crowing about it because it has proved to be my most successful book to date!

A lot had happened in those eight years. The advance of women’s studies and an escalating awareness of the roles of women in history, accompanied for a growing public thirst for knowledge of the human side of history and details of the minutiae of people’s lives, had led to a new interest in the lives of women in the past. Never more would medieval women be relegated to footnotes.

This month I have published the first full-length biography of Isabella, the so-called ‘She-Wolf of France’, a work that – in a different form - was rejected in 1981 on the grounds that it wouldn’t sell, as there was limited interest in the period.

Isabella enjoyed quite a high profile in her time, and her story is very dramatic, so it wasn’t very difficult to sell her this time around to my publishers. But proof of how far things really have moved on was made gratifyingly evident to me last year, when, to my great surprise and delight, I was commissioned to write a biography of a fascinating and enigmatic fourteenth-century lady, Katherine Swynford, the long-time mistress and later wife of John of Gaunt, and ancestress of the Tudors. It’s one of the great love stories in English royal history, but most people – if they have heard of it at all - know of it through a novel, Katherine, by Anya Seton, which was published over fifty years ago. I first read it back in the 60s, and was utterly enthralled. It was the ultimate story for me, one I have always wanted to tell. Yet it was not until very recently that the idea of writing a biography of a woman as obscure as Katherine Swynford became possible. I didn’t even consider proposing it myself; instead I suggested a biography of John of Gaunt. I realised how far things had moved on when my American editor suggested focussing on Katherine. It was the dream of decades come true – something that would have been inconceivable back in the 60s, 70s and 80s.

So what is the appeal of medieval biography? It might appear to be a process fraught with difficulties. To begin with, most of the sources are in Latin, French or Middle English. I can read the French and English – I had a great grounding in Chaucer in his original language at A-Level - but I employ an expert in medieval Latin at the University of York to help with the Latin. It’s exciting to see what re-translation of a source can reveal.

The next problem is finding the sources. Well, it’s not really a problem. Most of the main ones are in print and accessible online or through any good library or at the British Library, the National Archives and local records offices. Many medieval chronicles were translated and printed under the auspices of the Master of the Rolls (the Rolls Series) in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and a number of new editions have appeared more recently. I love nothing better than to delve away in old and even dusty volumes, seeking out those crucial pieces of information that can make all the difference to a book. For me, it’s a thrilling and compelling process. Some people can’t understand this – my daughter recently said to me, ‘Mum, you spent the 60s in a library?’ But I’m sure a lot of the biographers here today know exactly what I’m talking about.

The main problem with medieval biography is the sparseness of the material. In regard to Katherine Swynford, there isn’t one quote or letter; we have very little idea of what she looked like. Then there is the bias or prejudice evident in many sources, particularly the monastic ones, and the credulity and naivete of some medieval writers, who were inclined to believe, and embellish, myths and legends, and present them as fact. We must also remember that most writers were in holy orders and that they wrote, not as historians, but to promote the teachings of the Church and preach moral lessons.

Writing medieval biography, therefore, is mostly historical detective work, searching out, assessing, collating and chronicling numerous fragments of information, and trying to meld them together into a cohesive structure. That’s how I wrote my biographies of Eleanor and Isabella. It’s a challenging but fascinating process, and you never know where it’s going to take you.

Which leads me to the fun bit – the balanced art of drawing conclusions and constructing theories from the available evidence. In order to do this effectively, it’s important to collate your sources in a chronological framework. If you do that, it can be amazing what emerges.

For me, the chief appeal of medieval biography - writing about the lives of both women and men – is having the chance to flesh out these long-dead people, stripping away centuries of romantic myths, and replacing them with credible information drawn from more reliable sources and records. Trying, in effect, to reach the truth.

Recently a famous Tudor historian, who shall remain nameless, asked me what my aim was in writing history books. I told him I was trying to discover the truth – at which he laughed (not unkindly, I might add). It’s true that, compared to the Tudor period, little is known about the Middle Ages, and we can never know the whole truth; but if you approach what evidence there is with caution, insight and integrity, you may well reach some approximation of the truth.

I’m sure I’ve probably struck a few chords with all the biographers in this room, because the things that make medieval biography so appealing to me can be said to apply in some ways to all biography. Yet all these elements come together in regard to writing about the Middle Ages, and for me that’s the chief attraction. It’s the challenge of making a lot out of a little that gives me a buzz.

All I’m counting on now, with history becoming such a crowded and popular market, is that the illustrious biographers here today don’t all suddenly discover that medieval biography appeals to them too!

SEPARATING FACT FROM FICTION

Alison Weir at the Edinburgh International Book Festival, 2007

4**** review by Rosamary Goring

In Alison Weir's absorbing event there was an echo of happy flight from reality as she transported her listeners to fourteenth-century England, when Katherine Swynford, John of Gaunt's beautiful mistress and wife, became public enemy number one. As with any medieval figure, there were scant facts on which Weir could base her biography, and much of her work was, she said, an act of inference. Solid spade-work has nevertheless allowed her to build a picture of a woman who appears appealingly modern in her sensuous relationship with Gaunt, and in the degree of control she exerted over her own life. Weir's interest in Katherine was infectious, and she quoted liberally and vividly from that era's equivalent of the gutter press, namely England's fine monastic chroniclers, who variously reviled Katherine as a witch, whore and she-devil.

BOOK OF A LIFETIME: KATHERINE by Anya Seton

By Alison Weir, The Independent, September 2005

My favourite underrated novel is one that was celebrated in its own day, but which, despite being widely popular, fails to get the recognition it deserves today, possibly because it is wrongly perceived by many to be a lightweight romance. I am talking about Katherine by Anya Seton, first published in 1954.

By the early 1970s, the traditional historical novel, based on an actual historical figure or event, was a debased genre. It had enjoyed its heyday in the third quarter of the twentieth century, yet amongst all the trite and superficial tales of Tudor roses and tragic queens, there was a considerable number of brilliant gems - and none more brilliant than Anya Seton`s epic opus, Katherine.

Katherine tells the poignant story of Katherine Swynford, the famous ancestress of the Tudors, who was for twenty-five years the mistress of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, before he married her as his third wife, three years before his death in 1399. Set against a vivid and masterfully evoked backdrop of fourteenth-century England, in the time of the Black Death and the Peasants` Revolt, the narrative traces Katherine`s life from her arrival at court as a penniless ward of the Queen to her becoming the first lady in the land. The characters are marvellously drawn, and in John of Gaunt we have, according to one reviewer, the sexiest literary hero since Rhett Butler. Katherine herself is a strangely beautiful woman, who has an earthy yet spiritual appeal. The American author, Anya Seton, spent years researching her book, travelling to many places in England associated with her subject, and striving to ensure that her story was historically sound; the result is a convincing mix of fact and fiction, as my researches show.

Both this novel, and its author, were highly controversial when it was published in 1954 to acclaim on both sides of the Atlantic. Seton`s private life was colourful, and her sympathetic portrayal of the adulterous lovers, whose story has a happy ending, was regarded by the straight-laced critics of the fifties as “obscene and evil” and a triumph of vice over virtue. Plans were made to film the book with Charlton Heston as John of Gaunt and Susan Hayward as Katherine, but the project was abandoned because Hollywood dared not portray the hero and heroine living in sin, producing four bastards and enjoying an unmerited happy ending.

I first read Katherine when I was fifteen, and was entranced. I had become passionately interested in history a year earlier, and had already devoured the novels of Jean Plaidy and Margaret Campbell Barnes. But Seton`s captivating tale and her delightful style of writing were infinitely superior to anything I had read before, and I went scurrying off to the history books to find out more about Katherine. Sadly, there was very little to discover, for she was virtually ignored by historians.

Since then, Katherine has remained an inspiration and the benchmark by which I judge historical novels. For forty years, I have remained fascinated by the story told in its pages, and when, last year, I was commissioned to write a non-fiction book about Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, it was literally a dream come true for me. That book had, I realised, always been inside me, yet until recently it would have been impossible to write a full-length biogrophy of a woman like Katherine, because she simply would not have been considered important enough; most writers would have devoted just a paragraph, or a footnote, to her. Yet her story is important, and it deserves to be told.

It seems that I am not the only one for whom Katherine is a favourite novel. During the past year or so, at the many talks I have given, I`m usually asked what book I`m working on next, and when I say a biography of Katherine Swynford, there is invariably a frisson of excitement in the audience, and it usually turns out that most people have read the novel and been captivated by it. In 2003, Katherine was voted into the top 100 most popular books of all time by viewers of the BBC`s The Big Read . That same year, it was republished in the UK, and in 2004, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of its first publication, the full, unabridged text, which had never before been available in Britain, was reprinted in the USA.

I re-read Katherine recently, and it had lost none of its magic. Every sentence was a joy. I`m told that my own non-fiction books read like novels, and that people who used to read historical novels now read non-fiction historical books like mine. If my biography of Katherine Swynford is half as popular as the novel that inspired it, and if I can help to bring this novel to an even wider audience, and in so doing restore a forgotten gold standard in historical novel writing, then I will feel I have really achieved something.

THE SCANDALOUS DUCHESS

BBC History Magazine, Vol. 8, No. 9, September 2007

John of Gaunt's mistress Katherine Swynford is the subject of a new book by ALISON WEIR, which dispels the myth of a scheming enchantress and reveals her to be a most influential figure of the 14th century

She was "a famous adulteress" and she occupies a unique place in British history. The subject of great scandal and notoriety, who was denigrated as an "abominable enchantress", she was the mistress and friend of a royal prince for a quarter of a century, their affair having begun soon after he married a desirable young bride. Years later, after his wife had died and he married her, controversy and criticism surrounded their union, for she was thought to be far below him in status, morally unacceptable and highly unsuitable in many respects. Before long, however, her personal qualities won her acceptance and respect.

Sounds familiar? Indeed it does, but this is not about Camilla, Charles and Diana. It is the story of a fascinating woman who lived more than 600 years ago, the ancestress of our present monarch, and a lady who has been so neglected by historians that no one has ever, until now, written a proper biography of her. Instead, she is known to us largely through the pages of a popular romantic novel. That woman was Katherine Swynford, and she was one of the most important female figures of the late 14th century. Her partner in adultery, and later her husband, was John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, fourth son of King Edward III and one of the most powerful and celebrated figures of late medieval England.

The facts of Katherine's eventful story are known to us, but the details are surrounded in mystery, or obscured by time. Nearly everything about her is controversial. Her ancestry, the important dates in her life, the number of children she bore, her character, what she looked like, and - above all - her relationship with her princely lover. In approaching her life story, the historian is continually weighing up a balance of probabilities and possibilities, yet from the fragmented information we possess - even the lives of queens were not well-documented in this period - some credible inferences may be drawn, and some surprising conclusions arrived at.

Katherine Swynford was born around 1350, the daughter of Paon de Roet, a knight of Hainault (now part of Belgium). Her mother's name is unknown, but she may have been a connection of the House of Avesnes, the ruling family of Hainault. Paon de Roet came to England in the train of Philippa of Hainault when she married Edward III in 1328, and in the mid-1350s, his two younger daughters, Katherine and Philippa, were fortuitously placed in the household of the kindly Queen, their countrywoman. It may have been in 1360, when she was just 10, when Katherine was transferred to the household of Blanche of Lancaster, the young wife of John of Gaunt, to help in the nursery. She quickly won the respect and affection of her employer, with whom she was to remain for eight years, proving herself pious, intelligent, capable and good with children.

Around 1362, when she was 12 - the youngest age at which the Church permitted wives to cohabit with husbands – Katherine was married to John of Gaunt's retainer, the impecunious Sir Hugh Swynford, and found herself mistress of the poverty-stricken Kettlethorpe Hall in Lincolnshire, which must have come as a stark contrast to the splendours of the Lancastrian palace of the Savoy in London or the great castles of Leicester, Hertford and Kenilworth. But Katherine showed her mettle, immersing herself so enthusiastically in the life of the manor that for decades afterwards she would be known as 'the Lady of Kettlethorpe'. Following her marriage, she divided her time between her husband's estates and the Lancastrian court, while bearing a son, Thomas, and two, possibly three, daughters to one of whom the Duke and Duchess of Lancaster stood as sponsors.

Katherine's younger sister Philippa had married one of the King's esquires, Geoffrey Chaucer, who would later gain renown as a poet and the author of 'The Canterbury Tales'. Chaucer appears to have already earned the friendship and admiration of John of Gaunt, and his career at court was boosted by his sister-in-law's connections with the Duke. One of Chaucer's earliest poems was the beautiful elegy he wrote for the Duchess Blanche, who died in childbirth in 1368, and it bears testimony to the overwhelming grief of her husband.

Katherine herself was widowed in 1371, when Sir Hugh Swynford died while on campaign with the Duke in France. John of Gaunt had just remarried for political reasons, his bride being Constance of Castile, through whom he was to claim the crown of Castile. Although she was young and beautiful, the marriage never had a chance to succeed because it would appear that when Katherine, a destitute widow, appealed to the Duke, her overlord, for help, he succumbed to her allure and made her his mistress, probably in the spring of 1372. The course of their affair is charted to a degree by a series of grants in registers, although the registers are incomplete so they do not provide us with a full picture.

There is a pattern to these grants that suggests the birth-dates of the four children Katherine is known to have borne the Duke during the course of their affair. They were all surnamed Beaufort, after a French lordship John had once held, and from them were descended the Royal Houses of York, Tudor, Stuart and every British sovereign since 1461. For this alone, Katherine Swynford is of key dynastic importance in the history of the British monarchy.

Although the lovers were discreet to begin with, by 1378 John was openly parading Katherine as his mistress, and provoking virulent criticism from scandalised monastic chroniclers, who accused her of being a witch and a whore. At court, however, and certainly in Lincoln, where Katherine was popular with the cathedral clergy, the affair was probably accepted and condoned. The Duchess Constance was more preoccupied with regaining her kingdom than trying to dislodge her rival, and Katherine's undoubted tact and personal qualities ensured that there was never any open rivalry between them. Indeed, Katherine was popular with the Duke's children by Blanche (she was governess to his two daughters), and she worked with John to bring some cohesion to a domestic menage that could easily have been highly dysfunctional. She helped to bind Lancastrians, Swynfords, Beauforts and Chaucers into a harmonious family group, which in itself is testimony to Katherine's warmth and generosity of character.

For all that he clearly loved Katherine, John of Gaunt, who apparently had a healthy sexual appetite, does not seem to have been faithful to her. They were often apart for long periods, and by his own later admission, he had many fleeting sexual encounters with women in his wife's household, although Katherine may not have known about these at the time.

Initially, the affair between the Duke and Katherine lasted for nine years. Then came the Peasants' Revolt of 1381 and the destruction of the Palace of the Savoy, a virulent attack on John of Gaunt, whose head the rebels demanded. It left him profoundly shaken and guilt-ridden, and he publicly renounced Katherine and separated from her, a decision in which she seems to have concurred.

For the next few years, Katherine lived mainly at Kettlethorpe or in Lincoln, where she leased a fine house near the cathedral. The Duke was reconciled to Constance and thereafter concentrated his energies on claiming her kingdom. He remained in touch with Katherine, though, and she helped him financially with his military expedition to Spain, a venture that would ultimately end in failure, the crown he had so long sought eluding him at the last moment.

In 1389 John finally returned to England, and two years later we find a record of Katherine stabling 12 horses in his household. Bound already by their shared interests in their growing family, it would appear, from this and other evidence, that they had resumed their former intimacy. In 1394, the Duchess Constance died, and after John had obtained a dispensation and completed a period of service as Duke of Aquitaine, he returned to England and married Katherine. The wedding took place in January 1396 in Lincoln Cathedral.

Their marriage provoked far more scandal than their affair, for it was unheard of for a prince to marry his mistress, and many aristocrats felt that he had married far beneath him. The great ladies of the realm refused to acknowledge Katherine, who was now, for the brief period before King Richard II remarried later that year, the first lady in the land. But gradually, by her tactful and dignified behaviour, she won them round, and it was to her care and guidance that the king's young bride, the six-year-old Isabella of Valois, would be entrusted.

Early in 1397 Parliament legitimated the Beauforts, elevating them to the status of princes of the blood royal. This was certainly one of the reasons why John of Gaunt had married Katherine, but it is abundantly clear that their marriage was also made for love, for there is plenty of evidence for this in the Duke's financial settlements on her, and in his will, in which he left her, among other things, the beds in which they had slept together.

The remaining years of their marriage were overshadowed by political tensions and John's failing health. In 1398 the King's tyrannical and cruel sentence of exile on the Duke's beloved heir, Henry of Bolingbroke, led to John's final decline, and he retired with Katherine to Leicester Castle, where he died in February 1399. There is some evidence that he had been suffering from a venereal disease, the result of his earlier promiscuity, although this is not conclusive.

After his funeral, Katherine again retired to Lincoln, where she leased another substantial house in the cathedral close. She was generously treated by Richard II, notwithstanding his seizure of the Lancastrian estates, and by his successor, John's heir, now Henry IV, who, after he had deposed Richard and usurped the throne in 1399, referred to Katherine as "the King's mother" in official documents.

During the final years of her life, Katherine is not recorded at court and appears to have remained in Lincoln, living very quietly. Her Beaufort children were carving out glittering public careers for themselves, which must have delighted her, but the lack of evidence about her own life suggests that she was either immersed in grief or suffering declining health. She died in May 1403, and was buried in Lincoln Cathedral, where her daughter Joan Beaufort was later laid to rest beside her in a chantry chapel that still partly exists today.

Popular perceptions of Katherine either cast her as a romantic heroine or as the witch and whore of the chroniclers' fevered imaginations. Yes, hers is primarily a love story, but there was clearly far more depth to her than the romantic image would suggest. To have held the interest of John of Gaunt for so long, to have interacted socially in the cultivated circles in which he moved, and to have served as governess to the Lancastrian princesses all required intelligence, erudition and sophistication. The enduring affection of her family connections stands testament to her warmth, charm and good diplomatic skills. Although we have no true likeness to go on - there may be a hitherto-unsuspected vivid image in a chronicle - Katherine Swynford was undoubtedly beautiful. Her story is one of triumph and pain, and it ends most poignantly. In telling it,

I am fulfilling the dream of decades.

KATHERINE SWYNFORD lived through a dramatic age - the time of the Black Death, the Hundred Years'War and the Peasants' Revolt. She was acquainted with most of the great personalities of 14th-century England, including Geoffrey Chaucer and the controversial theologian John Wycliffe. Three kings - Edward III, Richard II and Henry IV - extended their friendship and patronage to her. She also enjoyed an affectionate relationship with two queens, Philippa of Hainault and Isabella of Valois. Her brother, Walter de Roet, was in the Black Prince's household. Katherine's eldest son, Sir Thomas Swynford, was gaoler to the deposed Richard II and implicated in his probable murder. Her daughter Joan Beaufort married the powerful Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland, and by 1450, thanks to the marriage alliances of their many children, Katherine's descendants were related to almost every noble family in England.

Their legitimation saw the Beauforts rise to the highest ranks at court and in society. Henry Beaufort became a cardinal, Thomas a duke and the guardian of the young Henry VI. John Beaufort, the eldest son of John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford, was created Earl of Somerset and died in 1410. His son, John Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, was the father of Lady Margaret Beaufort, who married Edmund Tudor, Earl of Richmond, and became the mother of Henry VII, the founder of the Tudor dynasty.

Through her granddaughter Joan Beaufort, who married James I, King of Scots, Katherine was the ancestor of every Scottish monarch from 1437 onwards, and thus of the royal House of Stuart following the union of the crowns in 1603. Another granddaughter, Cecily Neville, married Richard Plantagenet, Duke of York, by whom she was the mother of the English Kings Edward IV and Richard III, making Katherine the ancestor of every English monarch since 1461. Five American presidents, among them George W Bush, are also descended from her.

KATHERIN£ SWYNFORD is (he subject of Katherine, by American author Anya Seton, one of the most enduringly popular novels of the 20th century. First published in 1954, when it was branded as "obscene and evil" by critics, it has never been out of print, and made the top hundred favourite books in the BBC's' The Big Read' in 2003.

Seton spent four years researching the novel, and made worthy efforts to achieve historical accuracy, but hers is essentially a romantic portrayal, which reflects the values of her time and tells us perhaps as much about Anya Seton as it does about Katherine Swynford. Moreover, a great deal of research has been done since it was written.

Thus we have Katherine, as Paon de Roet's younger daughter, growing up in a convent (for which there is no evidence), and marrying Sir Hugh Swynford in 1367, five years later than she probably did in real life. They have two, not four, children, and Sir Hugh - for whose loutish character there is, again, no evidence - is murdered, a fictional assertion that is still accepted as fact by some, so great is Seton's reputation for veracity. This murder paves the way for Katherine to become John of Gaunt's mistress. Their romance has been simmering ever since she first

came to court.

After John's renunciation of Katherine Seton has her visiting the mystic anchoress (a religious recluse), Julian of Norwich, and in time achieving peace of mind. Later, one of the Suttons, a prominent Lincoln family, proposes marriage to her. However, John of Gaunt returns to England and claims her for his wife, thanks to the machinations of the Beaufort family.

Most of this is pure fiction, but so well-told that it reads convincingly and reflects the breadth of Seton's research. Notwithstanding its factual errors, Katherine is beautifully written, and remains my favourite historical novel. It has also been the inspiration for my biography.

KATHERINE SWYNFORD by Alison Weir, Heritage Today, UK, 2007

One of the greatest love stories in English history is that of Katherine Swynford and John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, fourth son of Edward III and one of the most celebrated figures of mediaeval England;.

Only the bare facts of this poignant tale have come down to us; there are no surviving love letters, and we know only that Katherine was very beautiful – not what she actually looked like. Born in Hainault around 1350, she was brought up by Philippa of Hainault, queen of Edward III of England. At ten, Katherine moved to the household of Blanche of Lancaster, the wife of John of Gaunt, to help in the nursery, and two years later, she was married to John`s retainer, Sir Hugh Swynford. Following her marriage, she divided her time between his Lincolnshire estates and the Lancastrian court, whilst bearing four children.

Katherine`s sister Philippa had married a royal esquire, Geoffrey Chaucer, later renowned as the author of The Canterbury Tales. One of his earliest poems was the beautiful elegy he wrote when the Duchess Blanche died in childbirth in 1368, which bears testimony to the overwhelming grief of her husband.

Katherine was widowed in 1371. John of Gaunt had just married Constance of Castile, but their union never had a chance to succeed, because it appears that, when Katherine, a destitute widow, appealed to the Duke for help, he succumbed to her allure and made her his mistress.

The course of their affair is charted by a series of grants in John of Gaunt`s surviving registers. The pattern of these grants suggests the birth-dates of the four children that Katherine bore the Duke. They were all surnamed Beaufort, and from them were descended the Royal Houses of York, Tudor, Stuart and every British sovereign since 1461. Thus Katherine Swynford is of key dynastic importance in the history of the British monarchy.

Although the lovers were discreet to begin with, by 1378, John was openly parading Katherine as his mistress, and provoking virulent criticism from scandalised monastic chroniclers, who now denigrated her as a witch or a whore.

During the Peasants` Revolt of 1381, the rebels wantonly destroyed John of Gaunt`s Savoy Palace in London. Profoundly shaken and guilt-ridden, and he publicly renounced Katherine. But they remained in touch, and by 1391, they had become lovers again.

In 1396, a widower once more, John married Katherine. This provoked a great scandal, for it was unheard of for a prince to wed his mistress, and many felt that John had married far beneath him. But gradually, thanks to her dignified behaviour, Katherine became accepted. Early in 1397, Parliament legitimated the Beauforts. This was one reason why John of Gaunt had married Katherine, but clearly their marriage was also made for love; in his will, he left her all the beds in which they had slept together.

John of Gaunt died in 1399. After his funeral, Katherine retired to Lincoln. She died in 1403, and was buried in Lincoln Cathedral. Her tale is one of triumph and pain, and it deserves to be accounted one of the greatest love stories in history.

From the Lincolnshire Echo, November 2007:

"I FIRST read Katherine in the late 60s, and was enthralled; and I was no less enthralled when I read it again, for the umpteenth time, last year," historian Alison Weir writes. Speaking of Anya Seton's novel about Katherine Swynford, who was famous as the mistress and later the wife of John of Gaunt, Weir says "it still inspires and moves" her and now she has published her own book exposing the scandalous story.

Approaching the subject of the medieval royal mistress from a factual stance, the first full-scale biography is proving very popular with Lincolnshire readers. Weir will be visiting Lincoln next week to promote the book and her event has already sold out - but it's not surprising, given Katherine's county connections.

The daughter of Payne de Roet, one of Edward Ill's heralds, and the sister of Philippa de Roet, who married Geoffrey Chaucer, Katherine first married Sir Hugh Swynford, an English knight from the manor of Kettlethorpe in Lincolnshire. She later married John of Gaunt in 1396, and the service took place in Lincoln Cathedral. Katherine died in 1403 and her tomb is in Lincoln Cathedral.

"This book is very special to me, because in writing it I have fulfilled a long-standing ambition to tell Katherine's story, an ambition I have cherished for more decades than I care to remember," writes Weir. "Its publication is no less than a dream come true."

From the Dartford Messenger, July 2008:

Anne Boleyn and Chaucer's sister-in-law, Katherine Swynfor,d are the latest subjects of books by the popular Alison Weir. The best-selling historical writer talks to Deborah Penn about her forthcoming visits to Kent when she will be giving talks about Henry Vlll's wives and the scandalous Swynford who was branded a "witch and a whore".

Weir has a wonderful way of bringing history to life. Her popular history books are as gripping as novels. She sweeps the reader along with a pacy, vivid style. She is a frequent visitor to Kent and is looking forward to her three dates in the county.

"I love Kent. It's one of my favourite places," said Alison, who has an impressive pedigree in Tudor history. "I had relatives at Ditton, near Maidstone, and often visit Hever Castle and Penshurst Place. Kent was an important stopping off place for Henry VIII on the way to Dover and Calais. He stopped at Otford, Leeds Castle and Charing, and at Rochester and Dartford on the way to Greenwich."

Alison's first talk in Kent will be on Henry VIII's wives, and she will follow this up with talks on Katherine Swynford, whose brother-in-law was Geoffrey Chaucer.

Her fascination with history dates back to her childhood. She explained: "I have been interested in history since the age of 14 when I read my first adult novel, a rather lurid book called Henry's Golden Queen about Katherine of Arragon. I was so enthralled that I dashed off to read real history books to find out the truth behind what I had read, and so my passion for history was born. By the time I was 15 I had written a three- volume reference work on the Tudor dynasty, a biography of Anne Boleyn based partly on contemporary sources, and several historical plays. I had also started work on the research that would one day take form in my first published book, Britain's Royal Families."

Her non-fiction books have been described as "popular" history, but she defended her style, saying: "History is not the sole preserve of academics. History belongs to us all. If writing it in a way that is accessible and entertaining, as well as conscientiously researched, can be

described as popular, then yes, I am a popular historian and I am happy to be one."

Alison, married with two children now in their twenties, was born in London but now lives in Carshalton, Surrey. She trained as a history teacher, but became disillusioned with "trendy teaching methods". Her first book was published in 1989, and from 1991 to 1997 she ran a school for children with learning difficulties.

Alison's next non-fiction book, The Lady in The Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn, due to be published in autumn 2009, tells of Anne Boleyn's arrest, imprisonment and execution, exploring the development of the romantic legends surrounding this extraordinary Queen.

Alison maintains that they met at court. She said: "Henry knew her family and I'm sure he came to Hever, staying at the nearby royal palace at Penshurst which he used as a base."

She takes issue with the recent film, 'The Other Boleyn Girl', especially the execution scene, which was filmed at Dover Castle and showed Anne in turmoil.

Alison said: "Anne Boleyn was composed at the scaffold. She looked cheerful. She was so incredibly brave. No film has ever depicted scaffold etiquette. There were speeches, prayers and disrobing. It was a long-drawn-out ordeal. They also had to wait five minutes before the actual execution in case there was a reprieve."

The paperback version of Alison's Katherine Swynford will be published on August 7 (Vintage, £8.99) and tells the story of an exceptional woman whose colourful existence was played out against a vivid backdrop of court life at the height of the age of chivalry. She knew most of the great figures of the time, including her brother-in-law, the poet Geoffrey Chaucer. Katherine lived through the Hundred Years War, the Black Death and the Peasants' Revolt, and her story gives unique insights into the life of a medieval woman. Alison said: "This is a love story, one of the greatest and most remarkable love stories of medieval England. It is the extraordinary tale of an exceptional woman who became first the mistress and later the wife of John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, one of the outstanding princes of the high Middle Ages. Dynastically she is an important figure. She was the mother of the Beauforts and through them the ancestress of the Yorkist kings, the Tudors, the Stuarts and every other British sovereign since, plus five American presidents - a prodigious legacy for any woman."

Katherine was branded "a witch and a whore", and so was born the legend of the "famous adulteress", the subject of scandal and notoriety, linked to John of Gaunt for a quarter of a century before they married.

Alison said: "Katherine's is essentially a love story. History is full of wonderful stories and amazing characters. I feel very privileged to be able top bring them to life in both my non-fiction books and my novels. In an age when history is perceived to be 'dumbed down' in schools, and on television and film, we can all learn from the past."

ALISON'S HISTORIC FIND

A rare portrait of Elizabeth I, which has never been reproduced or displayed, has been uncovered by historians Alison Weir and Tracey Borman in the Duke of Buccleuch's collection at Boughton House, Northamptonshire. It shows Elizabeth I as a teenager alongside siblings Edward and Mary, father Henry VIII and his jester, Will Somers. The picture is a copy of a panel painting thought to date from the 1550s, the whereabouts of which is still unknown.

Portraits of Elizabeth I before her accession are rare. This new image suggests that the much-debated picture of the 'unknown lady'at the National Portrait Gallery and other inconclusively identified portraits at Syon House, Audley End and Berry Hill are of Elizabeth as princess.

(For more information see the Children of England page)

KETTLETHORPE

The Manor House of Katherine Swynford

In 1356 one Thomas Swynford bought from John de la Croy the manor of Kettlethorpe in Lincolshire, which was to become the chief seat of the Swynfords until 1498; it would also become Katherine's marital home and be forever associated with her. Kettlethorpe is not far from Coleby, a property owned by the Swynfords since 1345.

Kettlethorpe was to become inextricably linked to Katherine in her own lifetime; for forty years she was known as the Lady of Kettlethorpe, and her memory is very much alive there today for the many visitors who make the journey — some would say pilgrimage — to this pretty, quiet but rather isolated Lincolnshire village, which is situated about twenty feet above sea level, and lies twelve miles west of Lincoln, just north of the border with Nottinghamshire. The River Trent flows west of Kettlethorpe, and the Fossdyke meanders along its eastern and northern boundaries. It is 'a romantic spot, embowered by trees'.

The manor took its name from a Viking who is said to have settled there in the ninth century. His name was Ketil, and the place he lived in became known as Ketil's Thorpe (or village), which over time became corrupted to Kettlethorpe. There is no mention of the settlement in Domesday Book, so it must have been very small, if indeed it still existed in 1086, in which case, the story of the Viking settler may have been an oral tradition preserved in local places such as nearby Newton-on-Trent, which is on record as a Domesday village. In fact, there is no mention of Kettlethorpe in historical documents until 1220. The de la Croy family had come into possession of it by 1287.

The present Kettlethorpe Hall incorporates fragments of the mediaeval house that Katherine knew, and is still surrounded by a moat. All that survives of the original hall are interior walls in the two barrel-vaulted cellars, the remains of a passage from those cellars that is reputed to have to the Church opposite, a blocked fourteenth-century doorway and some stonework on the southern elevations, a few carved heads and, standing apart, a ruined yet imposing fourteenth-century embattled and buttressed stone gatehouse with sunken mouldings, a survival probably from the 1370s, when Katherine was converting Kettlethorpe into a residence of some magnificence.

The gatehouse was reconstructed in the early eighteenth century, but not entirely successfully: the lower stones were reassembled authentically enough, but the upper parts owe much to the imagination of the builder who carried out the restoration. To the left is a mediaeval mounting-block, three steps high. We might imagine Katherine standing by it with a stirrup cup, bidding Sir Hugh Swynford farewell as he rode off to war.

When Katherine came to Kettlethorpe, after living in luxurious royal palaces since her childhood, she must surely have been dismayed by its poverty. The place was in serious disrepair. Even in 1372, after she had lived there on and off for the best part of a decade, it was 'ruinous, and the land sandy and stony and out of cultivation'; the only crops it would support were hay, flax and hemp, while the meadow was frequently flooded by the overflow from the nearby River Trent.

As lord of the manor, Hugh had the right to appoint priests to the twelfth-century parish church of St Peter and St Paul that stood to the north of the house,' a privilege that Katherine herself would one day exercise. In March 1362, Hugh presented one Robert de Northwood as rector. Katherine would have had frequent dealings with Northwood, who may have acted as her confessor when she was at Kettlethorpe; and because the manor population was small, she probably came to know everyone else quite well too.

In all, the Swynford holdings in the area comprised around three thousand acres, most of which was forest — prime hunting ground for the lords of the manor. When she was not pregnant, Katherine, like most ladies of rank, probably rode out with her husband and helped to put food on the table.

For Katherine, life at Kettlethorpe must have come as a shock after years of living in luxurious royal households, but it appears that she faced the challenge with equanimity and resourcefulness, taking her position as lady of the manor seriously.

On 26 June 1372 Edward III assigned Katherine, now widowed, her dower and she gained control of Kettlethorpe until such time as her young son, Thomas Swynford, came of age. That year she probably became John of Gaunt’s mistress, and their eldest child, John Beaufort, was probably born at Kettlethorpe in 1373. John of Gaunt’s Register suggests he visited Katherine there in September 1374. In 1377 he made her a gift of oaks for the repair of the manor.

From about 1380 Katherine’s sister Philippa, the wife of the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, was living with her at Kettlethorpe, after the breakdown of the Chaucers’ marriage. With the young Swynfords, Beauforts and Chaucers crammed into the manor, it would have been a chaotic household, with all the building works that were going on at this time, and of course the lady of the manor was often away. Katherine was probably with John of Gaunt when he was at Leicester Castle on 4 October 1380, for on that day he issued letters patent permitting her to cut down oak trees at his manor of Enderby, 'and to sell or carry this wood wherever she wishes, and use the profits for her own use'. It was probably used for the ongoing renovations at Kettlethorpe, which by now must have begun to look very imposing indeed; it was perhaps in this period that the great stone gateway was built. To all appearances, Katherine's was now a lordly household reflecting the wealth and social position of its mistress.

It was to Kettlethorpe that Katherine returned after Gaunt publicly repudiated her in 1381. She divided her time between the manor and her house in Lincoln, and was at pains to conserve and improve her son’s inheritance. Thomas Swynford took possession of Kettlethorpe in 1395, but he was often absent in the service of John of Gaunt, so Katherine remained in control. The following year she married John and became duchess of Lancaster. After her widowhood in 1399, she lived mainly in Lincoln. Kettlethorpe, with its frequently flooded meadow, may have been too damp for her as she advanced in years, but the records show that she still took an interest in the affairs of the manor.

After Katherine died in 1403, the Swynfords lived on at Kettlethorpe. In 1498 their line died out and the manor descended in turn to the Beaumonts, the Meryngs and others, before coming into the possession of the Amcotts family in the mid-eighteenth century. Their arms are still displayed above the front door. In the mid-seventeenth century the brick walls that still encircle the gardens

were built, while the hall itself was largely remodelled in 1713, at which time the fourteenth-century gatehouse was probably reconstructed. A drawing of the refurbished house, then called Kettlethorpe Park, survives from 1793, and shows it to have been a large

but undistinguished residence. In the early nineteenth century the hall was allowed to fall into a decline, and in 1857, Weston Cracroft-Amcotts had it demolished and built a plain redbrick Victorian house, into which was

incorporated some of the mediaeval fabric surviving from Katherine's time.

That is the house that stands today, in seventeen acres of grounds. Traces of Katherine Swynford's deer park also survive. In 1983 Kettlethorpe was purchased by the Rt Hon. Douglas Hogg, QC, MP, Viscount Hailsham, whose coat of arms, like that of the Swynfords who once inhabited the manor, bears three boars'heads.

KETTLETHORPE CHURCH

The church of St. Peter and St. Paul is based on a medieval plan and the original main structure, which was wholly demolished before rebuilding in the 19th century, is thought to have contained 12th century elements. It is possible that Sir Hugh Swynford’s body was brought back from Aquitaine and buried here, but there is no record of it, or of any Swynford burials. There is now hanging in the West Porch a sketch of the medieval church dated 1793. A close study of this sketch confirms that nothing of the original structure now remains. The Tower resembles the original but must have been rebuilt. The nave was pulled down completely, destroying the original structure which contained work of the early 12th century. The Chancel must also have been rebuilt, possibly with some of the original stones, but conforming in plan only. This is borne out by the fact that in 1809 a Faculty was granted for the complete reconstruction of the Church.

In form therefore the Church dates from 1809.

THE HOUSE OF LANCASTER – A Brief Background

In 1267, Henry III created his second son, Edmund ‘Crouchback’, Earl of Lancaster. Two years earlier, Edmund had been made Earl of Leicester. He was the founder of the House of Lancaster. He died in 1296 and was buried in Westminster Abbey, where his tomb and effigy can still be seen.

Earl Thomas; Duke Henry; Duchess Blanche

Edmund’s eldest son, Thomas, inherited his titles. Thomas married a great heiress, Alice de Lacy, who brought him the earldom of Lincoln. He was therefore a great magnate, and also an active and aggressive opponent of the weak King Edward II. Thomas of Lancaster led the barons against Edward, but was executed in 1322.

He left no children, so when his titles were restored – which was within five years – they were given to his blind younger brother, Henry of Grosmont, who was loyal to the Crown. There was a third brother, John, who had been Lord of Beaufort and Nogent in France; Henry of Grosmont inherited these lordships when John died, probably in 1336.

Henry of Grosmont married Matilda de Chaworth [Chaah – worth], who bore him seven children, six of whom were girls. Five married into the great aristocratic families of England, extending the familial affinity of the House of Lancaster. The only son and heir was the second Henry of Grosmont, who was created Earl of Derby and succeeded to his father’s other titles on the latter’s death in 1345.

In 1351 this Henry, who could have been the model for Chaucer’s ‘perfect, gentle knight’, was created Duke of Lancaster. His landed interests were vast. He was the greatest peer in the kingdom, an experienced and masterly general, and staunchly loyal to Edward III. Sadly he had no son to succeed him, just two daughters, and when he and his wife and elder daughter died on the Black Death, he left the younger girl, the fair Blanche, as his heiress.

Blanche was the wife of John of Gaunt, Edward III’s fourth son, and it was through her that John of Gaunt inherited the dukedom of Lancaster, the earldoms of Leicester, Lincoln and Derby, and the lordships of Beaufort and Nogent. Beaufort was in Champagne, and it has been claimed that Gaunt’s bastard children by Katherine Swynford, who were surnamed the Beauforts, were born there. In fact Gaunt lost the lordship to the French in 1369, during the Hundred Years War, so he gave his bastards a name that was associated with his House but could not threaten his legal heirs.

On Gaunt’s death in 1399, his heir was his eldest son by Blanche of Lancaster, Henry of Bolingbroke, who usurped the throne later that year and became the first sovereign of the House of Lancaster. Since then, the duchy of Lancaster has been vested in the Crown, and today the Queen is Duke – not Duchess – of Lancaster. The offices of the Duchy of Lancaster still occupy part of the site of the Savoy, John of Gaunt’s fabled palace.

JOHN OF GAUNT

In its first incarnation, this book was to have been a biography of John of Gaunt. What follows is the original proposal.

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster was the fourth son of Edward III, King of England, and one of the greatest of all medieval princes. Fabulously wealthy, his myriad interests were both dynastic and international, and he was a key figure in the European politics of the Hundred Years War. He sired dynasties of kings.

Closer to home, however, he was viewed with hatred and suspicion as an open adulterer and a patron of the heretical John Wycliffe, which gave rise to vicious rumours that he was a changeling or that he intended to usurp the throne.

Gaunt, however, was unswervingly loyal to his sovereign and a man of great integrity, who was the virtual ruler of England during the minority of his nephew, Richard II. Although he did indeed take an interest in the doctrines of Wycliffe, he remained a devout Catholic. Furthermore, his ambition for a throne led him to Castile in Spain, not to Westminster.

Gaunt was dignified, honourable, reserved, often conventional in his outlook, and a typical aristocrat in his love of display and magnificence. His retinue was a chivalrous company organised according to the ideals of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. Although he was an indifferent military general, Gaunt was an efficient diplomat and capable statesman, and possessed 'a brilliant mind'. A cultivated man, he patronised the poet Geoffrey Chaucer, who became his brother-in-law, and may have commissioned the great medieval masterpiece, 'Sir Gawain and the Green Knight'.

What was not so conventional about Gaunt was his private life. In his teens, he fathered a bastard on Marie de St Hilaire, one of the damsels of his mother, Queen Philippa. This was not unusual. His first two marriages were made for dynastic reasons, as were all royal marriages in that era, but his third - incredibly for the period - was made for love, for he married his long-time mistress, which was certainly unconventional. Along the way he managed to father thirteen children.

John of Gaunt, who was named after his birthplace, was born in 1340 at the Abbey of St Bavon in Ghent, Flanders (above left). He was the sixth child, and fourth son, of the thirteen offspring born to Edward III (above centre) and Philippa of Hainault (above right). Edward III, who reigned from 1327-1377, is renowned as the King who started the Hundred Years War with France, after laying claim to its throne, and who was the victor of Sluys, Crecy and Poitiers. It was Edward who founded the Order of the Garter, and Edward who ended his otherwise glorious reign in a shameful dotage, in thrall to his rapacious mistress, Alice Perrers.

Gaunt's mother. Queen Philippa, was universally loved for her kindliness and feminine virtues. She turned a blind eye to her husband's infidelities, and confined her influence to the domestic sphere. When she died in 1369, of dropsy, her husband and children grieved for her deeply.

Gaunt's oldest brother was the famous Edward of Woodstock, the 'Black Prince' (above left) , who gained renown in the great battles of the Hundred Years War and became the hero of the English people. The Black Prince defied his parents in marrying his cousin Joan of Kent (above right), a noblewoman with a dubious reputation, and by her became the father of the future Richard II. The Black Prince's health declined over the years, as did his martial reputation, and after ordering a vicious massacre at Limoges, he died prematurely, a year before his father.

Four of Gaunt's other siblings died in infancy. One sister perished of the Black Death on her way to her wedding in Spain in 1348. Two other sisters died soon after their marriages. The eldest sister, Isabella, made a miserable alliance with a French nobleman, who quickly abandoned her. Gaunt's brothers Lionel, Duke of Clarence, and Edmund, Duke of York, were the ancestors of the royal House of York; Gaunt himself, as we will see, was the ancestor of the House of Lancaster. The youngest brother, Thomas, Duke of Gloucester, was murdered by order of Richard II in 1397.

Gaunt's was therefore a colourful, close but sometimes dysfunctional family. The young Prince was created Earl of Richmond at the age of two, and spent his early childhood at Windsor and various other luxurious royal residences, in the care of his nurse, Isolda Newman, who was pensioned off when he was six. Thereafter, Gaunt was raised in the privileged manner of a royal prince, learning the martial arts alongside more academic subjects.

In 1359, Gaunt was married to his distant cousin, Blanche of Lancaster, at Reading Abbey. Edward III was anxious to ally the interests of the monarchy with those of the powerful and often troublesome aristocracy, and he meant to do this through making great magnates of his sons. Blanche was the heiress of the great landowner. Henry, Duke of Lancaster, a descendant of Henry III, and Edward's intention was that Gaunt should inherit Duke Henry's estates.