The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn (2009)

"It would be hard to imagine a more thorough examination... Alison Weir is to be congratulated on her impartiality and sound judgement, because the temptation to reach a more imaginative conclusion must have been overwhelming." (David Loades, B.B.C. History Magazine)

"Weir is well equipped to parse the evidence, ferret out the misconceptions and arrive at sturdy hypotheses about what actually befell Anne. Her command of minutiae is impressive, as is her enthusiasm for even the most minor aspects of Anne's frequently distorted story. The Lady in the Tower does not hedge its bets about Anne's relative innocence and culpability, nor does it foster any illusions about the romanticizing of her story." (New York Times)

"What is impressive about Alison Weir's study is the author's refusal to be waylaid by unsubstantiated rumour or tradition, or anything approaching imaginative guesswork... Weir shows admirable forensic skills." (The Times Literary Supplement)

"For all of its intimate involvement in Anne's plight, The Lady in the Tower is most worthwhile for its larger overview. It winds up weighing Anne's influence on the life of her daughter. It describes the way interpretations of Anne's story have changed over the centuries. It points out that the present-day prevailing attitude (that Anne was 'the prime cause and mover of the Reformation') could be a sweeping overstatement. Most important, it does not hedge its bets about Anne's relative innocence and culpability, nor does it foster any illusions about the romanticizing of her story." (Janet Maslin, New York Times)

"A brave effort to lay bare the bones of the controversy." (Hilary Mantel, New York Times Book Review)

"It is a testament to Weir's artfulness and elegance as a writer that The Lady in the Tower remains fresh and suspenseful, even though the reader knows what's coming." (The Independent)

"A serious history,... but I loved the minute details about the arrest, imprisonment and execution..." (Daily Express)

"Weir's tremendously readable book reveals Anne as more of a politician than a wife... This book, by one of our best historical writers, does this strangely compelling woman justice." (Alexander Lucie-Smith)

"Acclaimed novelist and historian Weir continues to successfully mine the Tudor era, once again excavating literary gold. [She] manages to introduce a fresh slant on the ill-fated second wife of Henry VIII. Weir's many fans and anyone with an interest in this time period will snap up this well-researched and compulsively readable biography." (Booklist)

"Weir is well equipped to parse out the evidence, ferret out the misconceptions and arrive at a sturdy hypothesis about what actually befell Anne. Her command of minutiae is impressive, as is her enthusiasm for even the most minor aspects of Anne's frequently distorted story.... The details... are at least as ghastly as they are fascinating... For all its intimate involvement in Anne's plight, The Lady is the Tower is most worthwhile for its larger overview." (International Herald Tribune)

"A most impressively researched book. Weir is able to offer a fresh perspective on the end of Anne Boleyn's life. What emerges is the most complete and compelling portrait available of Anne Boleyn in her last days. Weir's impeccable research and gift for storytelling help readers understand the fall of one of the most influential queens in English history and the world of Tudor England. A superb example of a nonfiction page-turner that history lovers cannot afford to miss." (Library Journal)

"Weir sifts methodically through the evidence, sorting out fact from myth... [She] knows her sources well. She writes in an engaging way and adopts an even-handed approach... Anyone who has been attracted to the Tudors through the cinema or television will enjoy making the transaction from entertainment to history by reading her account." (Hugh Gough, Emeritus Professor of Modern History, University College, Dublin)

"A fascinating and informative read." (Historical Novels Review)

"An eminently judicious, thorough and absorbing popular history." (Publishers Weekly)

"Who needs fiction when history is as gripping as this? Weir cuts through the myths to find the real woman." (Saga magazine)

"The Lady in the Tower is reliant on shock value; it's remarkable in terms of the depth and richness of its historical research alone, [and] ideal for those interested in evaluating the evidence against Boleyn, or anyone who simply wants to be captivated by the fall of one of history's most fascinating and tragic heroines." (Failure Magazine, New York)

"Drawing on multiple original sources and written in Weir's incomparable prose, "The Lady in the Tower" reads like a novel. It's great history that's accessible to the average reader." (Huntingdon News Network)

"Weir adds intrigue and new insight to the story of one of England's most controversial historical figures. I couldn't help but look at Anne Boleyn in a new way. The Lady in the Tower is a finely crafted and enjoyable read, but I would expect nothing less from Alison Weir." (Curled Up With A Good Book)

"As always, Weir writes compellingly and well. She manages to give the impression of great scholarship while maintaining an interesting and accessible tone. The Lady in the Tower is another very good book for this impressive writer's résumé." (January Magazine)

"Alison Weir's magnificent biography focuses on the last month of Anne's life and the events leading up to the charges of adultery and incest for which she was beheaded. Weir's painstaking research is evident: the book examines every angle and cites source bias, credibility, and access to defend her analysis. The result is a measured, thoughtful and well-written account of Anne Boleyn's destruction. It is a must-read for any fan of the Tudors and their times." (www.thehistorylady.wordpress.com)

"Compelling stuff, full of political intrigue and packing an emotional wallop." (The Oregonian)

Above: Preliminary jacket designs. The necklace was especially made for the paperback shoot, but the final UK paperback jacket had a black background.

You can read my article, 'The Classic Book: Alison Weir celebrates a definitive biography of a Tudor superstar', in BBC History magazine, January 2020.

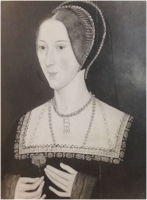

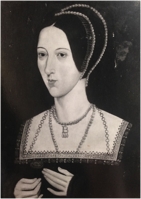

HOLBEIN'S PORTRAITS OF ANNE BOLEYN

This engraving by Wenceslaus Hollar, dated 1649 (above, right), is not - as has long been claimed - of the unlabelled British Museum drawing by Holbein above left, which is popularly identified as Anne Boleyn, and has been the subject of much academic debate. The engraving is clearly of a different portrait, and Hollar states beneath that Holbein drew it. No such Holbein is known. The discrepancies are obvious. The sitter is facing different ways, for a start. The jewellery, hood, neckline, bodice and sleeves are different. It was not Hollar who inscribed the drawing 'Anna Bullen' sometime after 1650, but probably someone who had seen Hollar's engraving (or one of its numerous copies) and assumed it was the same portrait; but Hollar did label his engraving 'Anne Boleyn, Queen of England'. It's often said that Holbein must have drawn or painted Anne, so it is possible, even likely, that Hollar did copy a lost drawing of her by Holbein. If so, the lady on the right is Anne Boleyn. And, that being so, given the close similarities in the features, the Brirish Museum sketch, also by Holbein, may also be her. There are four known portraits after Hollar, all called Anne Boleyn. Three, painted in the nineteenth century, are in private collections; the other is a late-17th-century version in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence.

THE BOLEYNS' HOUSE IN NORWICH

On 25th May 2016 I gave a talk at the historic Dragon Hall on King Street in Norwich. The hall was a high-status merchant's house and warehouse, and dates from 1427-30. During a tour of the building I was shown the dilapidated house next door. I had long understood that it was the town house of the Boleyns, but was told that that had been disputed.

Intrigued, I contacted Dr Elizabeth Griffiths of Exeter University, an expert on the Blickling Hall of the Boleyns, and asked if she had any information on the house on King Street. She did! She very kindly got back to me with a reference to the house next to Dragon Hall in an article by A. Shelley, 'Dragon Hall, King Street, Norwich: Excavation and Survey of a Late Medieval Merchant's Trading Complex', East Anglian Archaeology 112 (2005).

She also discovered, on looking at Blomefield's History of Norfolk, folio version, Vol. 3, a detailed plan of Norwich with numbered sites on King Street. Opposite St Julian's church (No 22, where the Lady Julian of Norwich had been an anchoress in the fourteenth century), on the other side of the street, there are four properties. Number 29 is called 'Meddeyz's Inn', then to the south stands number 28, 'Sir William Boleyn's City-house' (number 27 is 'Sir Miles Stapleton's City-house', and number 26 is Gournay's Place, facing on to the side alley. This street layout is confirmed on page 84 of Blomefield's vol 4 (on Norwich), and adds that number 28 was 'the house of Sir William Boleyn, knight, and after that of the Lady Anne Boleyn'.

An Anne Boleyn had held the property in 1474. This could have been Anne (b.1440, d.May 1510), daughter of Sir Geoffrey Boleyn, Lord Mayor of London (d.1463); she married (after 1463) Sir Henry Heydon (d.1504). More probably, she was Sir Geoffrey's widow, Anne Hoo, Lady Boleyn, who died in 1484, when the property may well have passed to her son, Sir William Boleyn.

The 'late Anne Boleyn' mentioned in 1549 - who must be the same 'Lady Anne Boleyn' who held the property after Sir William Boleyn - could possibly have been Queen Anne Boleyn. The title 'the Lady Anne Boleyn' was the form used by a peer's daugher, and Anne was styled the Lady Anne Boleyn from 1525-9, and then, after her father was created Earl of Wiltshire, as 'the Lady Anne Rochford', Rochford being his subsidiary title. After her death, many people would not have referred to her as Queen Anne, but as the Lady Anne. Yet I can find no evidence of her holding property in Norwich.

Another Anne Boleyn alive at the time was her aunt, Anne Boleyn, Lady Shelton, daughter of Sir William, but she didn't die until 1555, which rules her out. Then there was Anne Tempest, Lady Boleyn, the wife of Sir Edward Boleyn (d. before or in 1536), a younger son of Sir William. She died after 1536 - the date of her death is unknown. The house could have been part of her widow's jointure, which seems the likeliest explanation.

The Midday family owned the house later called Dragon Hall in the 14th century, which accounts for number 29 being known as Midday's Inn. Thus the Boleyns� house must be the one next door, the former number 28.

Sadly, it is derelict. A timber and brick upper facade remains, and a couple of doorways, but the interior may be occupied by pigeons. It is to be hoped that, one day, this historic house will be bought and restored. It's likely that Anne Boleyn knew the house in her infancy. Her sister Mary and brother George could even have been born there. It seems a crying shame that such an important building is being left to rot.

WHAT'S NEXT from the ALISON WEIR NEWSLETTER 2007

Now that the summer holidays are over, I will be starting work on my next non-fiction book, The Lady in the Tower. This will be a detailed account of the fall of Anne Boleyn, beginning with the plot to bring her down and looking in unprecedented detail at the events that took place over the seventeen days that she was in the Tower of London in May 1536 - events that culminated in her sensational trial and execution.

In writing about Anne Boleyn and this highly dramatic episode in the annals of England, I will be returning to the point where I first developed an interest in history. When I was seven, my father took me to visit the Palace of Westminster, and there, high up in the Prince's Chamber were Richard Burchett's full-length portraits of the Tudors. On having Anne Boleyn pointed out to me, and being told that she had had her head cut off, I was struck with awe and horror, as well as an enduring fascination. Seven years later, at fourteen, I read a historical novel featuring Anne, and was similarly struck again, and from then on I read everything I could find on her. It was the sheer drama of her end that fascinated me. I could barely imagine what it had been like for her...

Since then, I have written fairly extensively about the Tudor period, and am always thrilled to be revisiting it. I am no longer as obsessed with Anne Boleyn as I was all those years ago, and certainly don't see her in such a romantic way, but the fascination endures, and I am sure that there is much still to be learned about how she came to her doom.

I am aware that there have been many biographies of Anne, some brilliant, some controversial and some best forgotten. I've written about her myself in two books, The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Henry VIII: King and Court, and she features in three of my other books. Certainly her life has been extensively chronicled, both by historians and novelists, especially in recent years. Yet by its very nature, a full biography does not offer the scope for a detailed account of her final days, the most crucial in her story. There has never been a book devoted solely to her fall, and I think there needs to be, in order for us to make sense of it. Hence this commission.

Not only do I wish to focus on Anne's fall, trial and execution, but I also aim to look at their effect on her reputation, both in the immediate aftermath of her death and down through the centuries. Anne was notoriously unpopular, yet within two weeks of her beheading, sympathetic ballads were circulating in London. For her contemporaries, as for us today, that powerful image of the tragic and courageous Queen kneeling upright on the scaffold, waiting for the sword to strike, speedily overlaid previous hostile perceptions of her, which leaves one wondering what reputation she would have enjoyed had she died in her bed in old age.

I wish to look also at the legends that sprang up in the wake of Anne's execution. The strange tales of the fate of her body, the stories of ghostly carriages with headless horses and of spectres at the Tower of London - all these are part of the mythology of Anne Boleyn.

Above all, I want to delve deeper into the mysteries that surround her fate; to examine in detail the origins of the plot to destroy her, the roles of Henry VIII and Thomas Cromwell, the charges against Anne and the men accused with her, and the likelihood of their guilt. This is one of the grimmest, most notorious and most famous episodes in our history, and in revisiting it, and studying it in the depth that only a full-length book can allow, I hope to be able to lay some of the ghosts to rest.

You can hear me talking about The Execution of Anne Boleyn on the BBC World Service's Witness programme here: http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p03v870n

A NEW IMAGE OF ANNE BOLEYN?

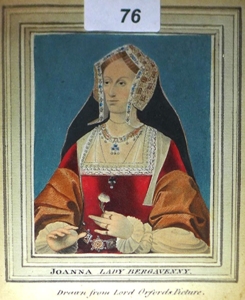

Browsing eBay recently, I was amazed to find myself staring at a portrait of Anne Boleyn I had never seen before. Given that there are only a few authentic portrait types of Henry VIII's executed second wife, plus a damaged medal from 1534 - the only image surviving from her lifetime - you might understand why I was riveted. The listing advertised a photograph of a print of a Tudor portrait once owned by Horace Walpole, which hung in the Holbein Room at Walpole's famous Gothick mansion, Strawberry Hill at Twickenham. The seller, Howard Jones, who is Hinterested in medieval and Tudor portraits and prints, stated that the painting had been incorrectly identified as Johanna Fitzalan, Lady Bergavenny.

Authenticated images of Anne Boleyn (National Portrait Gallery, Bradford Art Galleries and the British Museum)

He added: "The initial A on the necklace, the two additional initials [B and R] and other clues suggest this is a 'new' and one of the best surviving portraits of Queen Anne Boleyn. An engraving of Walpole's painting had earlier been made in 1798. This [Mr Jones's print] is a later more detailed copy made after the Strawberry Hill sale of 1842."

The print is of a half-length portrait of a woman in a lavish Tudor gown and gable hood. She wears a rich collar in which the initials B, A (in the centre) and R can clearly be seen. Her hood is decorated with As. She holds a carnation, or pink, also known as a gillyflower. The girdle at her waist, the richness of her hood and biliments, and the ornate jewellery all betoken a sitter of very high rank.

In two of the three authentic images we have of her, Anne Boleyn wears an English gable hood. She wore one to her execution. And yet, doubtless due to the proliferation of the portrait of her in a French hood - there are at least twenty-one versions - and reports that, when she first arrived at the English court, from France, in 1522, "you would have taken her for a Frenchwoman born", most people have a mental image on her in a French hood. But gable hoods were fashionable until the mid-late 1530s.

The A jewel on the necklace seems identical with one that Anne's daughter, the future Elizabeth I, is wearing (below), as a child, in the Henry VIII Whitehall dynastic group portrait at Hampton Court.

The R may stand for Regina (queen), which would date the portrait to 1533-6. Anne Boleyn's predilection for initial jewels is evident in her portraits, in which AB, B and HA (for Henry and Anne) jewels feature, and in the portrait of her daughter referred to above. They are rarely seen in other portraits of the period. The costume in the print is of a style more associated with the 1520s than the 1530s, but it's possible that it is not reproduced accurately in the print. Later prints and engravings usually look different from the portraits on which they were based.

The gable hood remained fashionable in the 1530s, but its lappets became shorter. Occasional examples occur of the longer version, such as in the portrait of Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, which has been dated to c.1535. Anne was a younger woman, of course, but - unlike today - fashion was then associated with rank, rather than with youth, and it was the magnificence of a queen's attire that was meant to impress.

Nevertheless, heavy collars like the one in the print had largely gone out of fashion by 1530. Given the costume, it is possible that - as Howard Jones has suggested - the R may stand for Rochford. From the time Anne's father was created Earl of Wiltshire in 1529 to her own ennoblement as Marquess of Pembroke in 1532, she used the style Lady Anne Rochford. A portrait of Katherine of Aragon, wearing similar costume, in the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (an 18th-century copy is in the National Portrait Gallery), has been dated to around 1530.

Some people have noticed that the sitter in the print has a strange swelling on her neck, and pointed out that the hostile Nicholas Sander wrote that Anne Boleyn had some swelling under her chin, but this is not visible in other representations of the portrait, and may just be a vagary of the artist who made the print.

I am indebted to Nicola Tallis, whose PhD thesis is on royal jewellery from 1464 to 1548, for checking inventories of jewels owned by Henry's queens and Mary Tudor - Anne's jewels were given to the future Mary I, who may have had them broken up or given them away - but she could find nothing that matched the jewellery in the print. This is not necessarily significant, as we don't have inventories for all the queens.

In Tudor times, according to Professor Ralph Houlbrooke from the University of Reading, a man gave his bride a wedding ring during their marriage service, and placed it on the fourth finger of her left hand. By this token, the sitter in the print is married, so if it is Anne Boleyn, the portrait must date from 1533. However, in the Hever Castle and Radclyffe portraits, and one sold at Sotheby's, which all show her hands, Anne is not wearing a ring on her fourth finger. It could be that the latter portrait type pre-dated her marriage, and the inscriptions of her as queen were added later, for none of these portraits date from her lifetime. But in some portraits Henry's queens are not portrayed wearing their wedding rings.

Both Sarah Gristwood and Joanna Marston, experts on flowers, identified the one the sitter holds as a pink, also known as a carnation or gillyflower. It was a symbol of purity. David Baldwin has pointed out that Elizabeth Wydeville, Edward IV's Queen, adopted it because it was associated with the purity of the Virgin and symbolised virtuous love and marriage. Sarah Gristwood says that the name gillyflower also meant 'queen of delights'. The word carnation is associated with coronation. Carnations are found in many representations of marriages and betrothals from the late Middle Ages, probably as a symbol of love and fertility. This flower was also a symbol of the Passion of Christ, and often appears in images of the Virgin and Child. This all suggests that, if the portrait was of Anne Boleyn, it was painted in 1533 to mark her marriage and coronation. If, however, the R does stand for Rochford, the flower may have symbolised purity, and we might be looking at a unique image of Anne Boleyn from before her marriage.

In 1795 a drawing of the portrait was used as a frontispiece in a book (above, left). Engravings of the portrait were made in 1798 and 1806 (centre and right). I already had a scan of the 1806 engraving, which had rung no bells with me simply because the details are not clear. Howard Jones thought there was a coloured copy of the Victorian print in the Royal Collection in the print Room at Windsor Castle, but I can find no trace of it on the Royal Collection website. A watercolour painting of Lady Bergavenny was sold by Criterion auctioneers of Islington in 2015 (below, left), and is apparently based on the 1795 engraving. It is labelled: 'Drawn from Lord Orford's picture', Lord Orford being either Sir Robert Walpole or Horace Walpole. None of these versions shows the detail that appears in the 1855 print, which is highly defined and very detailed, and I could see immediately that Howard Jones had good reason to suggest that the sitter was Anne Boleyn.

We don't know the full provenance of the painting on which the print is based. According to Howard Jones, "The original painting was given to Walpole by a friend, Miss Beauclerc, the daughter of the Duke of Marlborough. After the Strawberry Hill sale in 1842, the painting appears to have been lost, but this copy was made perhaps in the 1860s."

He added: "When I acquired the prints, there was a second image of sheet music superimposed on the Boleyn image. This second image gives the name of the printer in London and could be used to find the date when the prints were made. I have managed to find the relevant sheet and the publishers were Cramer, Beale and Chappell of 201, Regent Street, London. They made musical instruments and published sheet music. The company changed its name in 1861 when Chappell retired so the print should date from around 1850-1860."

In fact, it was probably produced in 1855, when the Strawberry portrait was sold again. In 1842 it had been purchased by John Jarman, a London art dealer, for £21, and sold on to Ralph Bernal, a politician and noted collector. He died in 1854, and his collection was sold in 1855. I am indebted to Sylwia Sobczak Zupanec, who found the Bernal sale catalogue in 'The Archaeological Journal' (Volume 17, 1860). This records that the portrait was "half-length, 16 inches by 12 inches. The costume is very rich, a crimson dress, with wide sleeves of cloth of gold." A coloured aquatint is in the British Museum (I am grateful to Howard Jones for this information), and a coloured copy of the print is in the National Portrait Gallery's Heinz Archive (above, right). The colours are stunning - and strikingly like those of Jane Seymour's attire in Holbein's portrait in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna.

The Bernal Collection was sold at auction in 4,294 lots by Christie and Manson in 1855, and 730 lots went to the Victoria and Albert Museum, but the there is no record of the museum owning this portrait.

And there the trail goes cold. I could find no record of what happened to the portrait after that. Thus the theory that the original portrait was of Anne Boleyn rests - for now - on evidence in the 1850s print alone.

In the Bernal sale catalogue there is a coloured drawing of the portrait (above, left), in which the face looks significantly different to the one in the print. It bears a striking similarity to the portrait of Anne Boleyn formerly at Nidd Hall, now in the collection of Bradford art Galleries. It also compares with the face shape in the 1534 medal, in which Anne is wearing a similar gable hood and a pendant cross that may be the same one in the print, although, according to stone sculptor Lucy Churchill, who made a reproduction of the medal and has studied it in detail, it is impossible to be certain that it is the same cross, and the lappets of the hood are shorter.

Joan, Lady Bergavenny, died before 1505 - some sources say 1508. The Complete Peerage gives her date of death only as 14th November. The identification as her may have been based on the supposed Is (for Iohanna) in the headdress, but even if they are Is, this does not take account of the R in the collar. It's common to find Tudor portraits incorrectly identified or labelled. The costume is much too late for 1505-8; the lappets of gable hoods were much longer then, and oversleeves did not come into fashion in England until about a decade later. The Bergavenny blazon was a barbed rose, and there's no evidence of that in the print.

There is a photograph of an original portrait called Lady Bergavenny in the Heinz Archive (above, right); on the back is a note: 'Inscribed on parchment on back of panel Lady Joanna Abergavenny, artist Holbein.' Two provenances are given: the Holme Pierrepont collection and the Seward collection. This cannot be the portrait on which the print is based. The Strawberry Hill portrait had an ornate frame, but the one in the Heinz Archive has a battered narrow wooden one, and no B or R can be seen in the collar. However, in 'The Gentleman's Magazine', in 1842, it was recorded that, in the Strawberry Hill version, there were three initials on the collar. The Heinz portrait is almost certainly a crude copy, and the fact that a copy was made strengthens the argument for the sitter being someone of importance, because there is unlikely to have been demand for more than one portrait of the obscure Lady Bergavenny. Thus it is clear that there were two portraits. The face in the Heinz portrait bears a resemblance to Anne's in the Bradford portrait.

Is the Strawberry Hill portrait still out there somewhere? Maybe, given the incorrect identification as Lady Bergavenny, it survives in a private collection and the owner does not realise its possible historical importance.

If the new identification is correct, this is a very different image of Anne Boleyn from those with which we are familiar, and it is just possible that the original was painted by Holbein. But until we can study the original portrait, the identification as Anne, and the artist, must remain conjectural.

ANOTHER POSSIBLE IMAGE OF ANNE BOLEYN

Until 2017, every reproduction of this image that I have seen was labelled Philippa of Hainault, queen of Edward III, the King who founded the Order of the Garter, but Roland Hui has recently suggested that the the AR on her pendant does suggest that it might be Anne Boleyn, who was queen when the Liber Niger (the Black Book of the Order of the Garter) was begun in 1534. It was perhaps completed about ten years later. The costume is correct for the 1530s, but not the 1540s. It's a crude portrait, but the sitter does have a pointed chin, as Anne did in authenticated images of her.

ALISON WEIR ON HER TALK AT BLICKLING HALL ON THE ANNIVERSARY OF ANNE BOLEYN'S EXECUTION, 19 MAY 2011:

"It was so special for me, speaking at Blickling Hall, the place where Anne Boleyn was probably born, on the anniversary of her death, and it was a very poignant moment when the wonderful consort Cantocordia performed O Death Rock Me Asleep just before I began speaking.

"The mood lightened later with the ghost talk and late supper, then at 11.45pm, a lady dressed (very authentically) as Anne Boleyn led us out into the grounds and we watched as she 'glided' across the front of the Hall, then down the blackness of the drive, where loads of cars had parked by the entrance gates. Suddenly, there was a barrage of flashes from cameras and phones - it was like the paparazzi. We stood there silently before the Hall for a while after midnight, but nothing appeared - did we ever think it would? In that atmosphere, you could believe it might!"

ALISON WEIR � THE LADY IN THE TOWER: THE FALL OF ANNE BOLEYN

This is the compelling story of one of the most tragic, cataclysmic and dramatic episodes in history: the last days of one of history's most charismatic, controversial and tragic heroines.

The imprisonment and execution of Queen Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII's second wife, in May 1536 was unprecedented in the annals of English history. It was sensational in its day, and has exerted endless fascination over the minds of historians, novelists, dramatists, poets, artists and film-makers ever since.

Anne was imprisoned in the Tower of London on 2 May 1536, and tried and found guilty of high treason on 15 May. Her supposed crimes included adultery with five men, one her own brother, and plotting the King's death. She was executed on 19 May 1536.

Mystery surrounds the circumstances leading up to her arrest. Was it Henry VIII who, estranged from Anne, instructed Master Secretary Thomas Cromwell to fabricate evidence to get rid of her so that he could marry Jane Seymour? Or did Cromwell, for reasons of his own, construct a case against Anne and her faction, and then present compelling evidence before the King?

Following the coronation of her daughter Elizabeth I in 1558, Anne was venerated as a heroine of the English Reformation. Over the centuries, her dramatic story has inspired many artistic and cultural works and has remained ever-vivid in England's popular memory.

Never before has there been a book devoted entirely to Anne Boleyn`s fall. Alison Weir has reassessed the evidence and woven a richly researched and impressively detailed portrait of the last days of one of the most influential and important figures in English history.

This is the only book on Anne Boleyn to focus exclusively on this, the most dramatic period of her life - especially the last 17 days, which she spent as a prisoner in the Tower of London. It demolishes many romantic myths and popular misconceptions about its subject. The author has used sources overlooked by other writers, and she offers a definitive answer to the question: was Anne innocent, or was she guilty?

ALISON WEIR WRITES:

"This is where my interest in history began, many years ago, with Anne Boleyn and the dramatic story of her fall. That interest has never abated - I have written at length on Anne in two earlier books, The Six Wives of Henry VIII and Henry VIII: King and Court, and in a number of unpublished works - and I know that it is shared by many: the crowds who visit the Tower of London to see the supposed site of her scaffold, or flock to Hampton Court, where Anne stayed in happier days, or to Hever Castle, her family home, or Blickling Hall, the place of her birth. The fascination is evident in numerous sites on the internet, the almost-regular appearance of biographies of Anne Boleyn, films and television dramas about her, and the numerous letters and emails I have received from readers over the years.

Yet never before - surprisingly - has there been a book devoted entirely to the fall of Anne Boleyn, and it was a deeply satisfying experience having the scope to research in depth this most discussed and debated aspect of Anne`s life. It allowed me to achieve new insights and to debunk many myths and misapprehensions. It was an exciting project, and I was constantly amazed at what I was able to discover.

Anne Boleyn has always been a controversial character. Even today, historians are rarely as impartial about her as they should be. But it is hard to look beyond that brave and tragic figure on the scaffold to the woman who had been the scandal of Christendom and the catalyst for the English Reformation. My research has revealed many fascinating aspects to her story, among which are the following:

* The reasons why Anne's enemies moved against her.

* Where Anne was imprisoned in the Tower of London.

* When her executioner was sent for.

* The real site of the scaffold on which she died.

* Where she is probably buried.

* Whether or not Anne was innocent of the charges laid against her.

I was pleased to be told that my approach to my subject could be described as `forensic`. It`s an apt word to apply to a book that contains not just a detailed account and analysis of Anne Boleyn`s fall, but also much graphic forensic detail - so much of it, in fact, that my editor felt he needed a stiff drink after reading the chapter on Anne`s execution.

Above all, this book was been a labour of love, as well as an exciting quest for the truth - or as near as anyone today can get to the truth."

A PORTRAIT OF ANNE BOLEYN

I have never forgotten my first visit to the National Portrait Gallery - a treasure house of wonders to a history-truck adolescent - where I came face to face with a portrait of Anne Boleyn by an unknown artist. Having spent several decades since researching Tudor history and portraiture and arriving at a rather less romantic view of Anne, I must confess that I still find this painting compelling and evocative. It entrances and it intrigues.

It may not be great art, and it is only one of several copies of a lost original painted from life between 1533 and 1536, but it is the portrait by which most people identify Anne, and captures the charm and wit of which contemporaries spoke. It bears testimony to the famous 'little neck' that was so soon to be severed by the executioner's sword, the 'black and beautiful' eyes that 'invited to conversation', and to Anne Boleyn's renowned elegance in dress. This is clearly the image of a queen who wanted to make a statement. Our eyes are drawn to her 'B' pendant, proclaiming her identity and her sense of her family's importance. There is no hint here of the disaster yet to come.

There are many versions of this portrait. These are the ones of which I'm aware:

L-R: Location unknown; Bridgeman; Dulwich College Picture Gallery; private collection, 18th century

L-R: Buccleuch Collection; location unknown; Hever Castle

L-R: Private collection; location unknown; private collection

L-R: National Gallery of Ireland; National Portrait Gallery; National Portrait Gallery at Montacute House; Radclyffe collection

L-R: Ripon Cathedral Library; Rosse collection; Royal Collection; private collection

L-R: Old Deanery, Ripon; private collection; Hever Castle; Loseley House

L-R: Hever Castle, 19th century; location unknown, showing 6th finger; Paul Workman, modern painting in my own collection; modern painting at Thornbury Castle.

FALSE PORTRAIT

The Holbein drawing above left, from the Royal Collection, is inscribed in a later hand ANNA BOLLEIN QUEEN. The inscription must be incorrect, as the sitter has blonde hair (Anne was a brunette) and her facial features are different from those in the authenticated portraits; her lips are fuller, and she has a double chin that is nowhere evident in other images. She is informally dressed in a nightgown with a fur collar and a plain cap, and it is unlikely that Anne would have been depicted in such intimate attire. The sitter is probably a lady of the Wyatt family, since the Wyatt arms appear on the back. A painting based on this drawing was sold at Christie's in 1923.

ACTRESSES WHO HAVE PLAYED ANNE BOLEYN

L-R: Laura Cowie in Henry VIII (1911); Henny Porten in Anna Boleyn (1920); Merle Oberson in The Private Life of Henry VIII (1933); Elaine Stewart in Young Bess (1953)

L-R: Vanessa Redgrave in A Man For All Seasons (1966); Genvieve Bujold in Anne of the Thousand Days (1969); Dorothy Tutin in The Six Wives of Henry VIII (BBC, 1970)

L-R: Charlotte Rampling in Henry VIII and his Six Wives (1972); Barbara Kellerman in Shakespeare's Henry VIII (BBC, 1979); Helena Bonham-Carter in Henry VIII (Granada TV, 2003); Jodhi May in The Other Boleyn Girl (BBC, 2003)

L-R: Natalie Portman in The Other Boleyn Girl (2008); Natalie Dormer in The Tudors (BBC, 2007-8); Miranda Raison in Anne Boleyn (Shakespeare's Globe, 2010); Clare Foy in Wolf Hall (2016)

ANNE BOLEYN: A WOMAN WRONGED

Feature by Steven Russell, East Anglian Daily Times, 2009.

We might moan at a programme like EastEnders and tut that the level of internecine plotting, violence and treachery is fanciful, but we have only to leaf through the pages of history to see it's been a facet of English life for hundreds of years. Take the rise and fall of Anne Boleyn, second wife of Henry VIII, who in less than three years went from a glorious Westminster Abbey coronation as queen consort to a shocking beheading at the Tower of London. It's a story that's captured the imagination of historians, writers, dramatists and schoolchildren who relish a gory outcome. Forty years ago, for instance, was the film Anne of the Thousand Days, starring Genevieve Bujold as the ill-fated queen and Richard Burton as Henry. "It's a dramatic event, the Queen of England being beheaded for treason!" explains author Alison Weir. "It was a huge scandal in its day: you've got sex, you've got trials, you've got an execution. You've got everything!"

Alison's new book, The Lady in the Tower, is the first devoted to the fall of Anne Boleyn. Many volumes have been written about the reign of Henry VIII, but they tend to talk about all of his six wives, rather than focusing on a brief but pivotal few months in the life of a single one - in this case the mother of Elizabeth I.

The king's initial love for Anne and his divorce from Katherine of Aragon - which triggered the split with Rome - changed the course of English history. And then Henry fell out of love with his Queen. Anne was accused of plotting the monarch's death, as well as adultery with five men, including her own brother. On May 19, 1536, the executioner's sword swung and the queen was dead. Alison Weir is convinced she went to her death a wronged woman - the victim of a systematic plot and a show trial whose result was never in doubt.

Mystery has surrounded the circumstances leading up to her arrest at the start of that month. Alison points the finger firmly at Master Secretary Thomas Cromwell, the king's chief minister, for playing, on Henry's fears and "spinning" existing rumours of sexual indiscretion to preserve his position. It wasn't, she believes, the King who prompted his Queen's fatal descent. Cromwell had once been a staunch supporter of Anne, but relations had cooled. When the Queen initiated a sermon in which it was suggested that wicked ministers ought to be executed, he started getting nervous - particularly as Anne appeared to be getting on better with her husband.

"It was his neck or hers," says Alison.

The King's long-standing anxiety about treason gave Cromwell one powerful lever. The Queen's nature - she hadn't been a meek and submissive wife, and was known to enjoy the admiration of men - presented other material with which he could work.

So the planets aligned against Anne. She was imprisoned in the Tower of London on May 2nd, found guilty of high treason on the 15th, and was executed four days later.

How did Alison come to her conclusions? Well, mainly by conducting an almost forensic examination of original documents kept in places such as The British Library and The National Archives and reassessing the evidence. It was a true labour of love, for this was where her passion for history arose as a teenager. By the time Alison was 15, she had written a three-volume work on the Tudor dynasty and a biography of Anne Boleyn!

"When you go back to the original sources, you maybe find there's much more than anyone's actually looked at - and that's what happened with this book. Or perhaps the sources have been dismissed by most historians and you think again: why?"

Eric Ives wrote a brilliant biography of Boleyn some years ago, she says, and was the first to push the theory that Thomas Cromwell was prime mover. In the context of the Machiavellian politics of the age, the minister, "a brilliant administrator and financial genius" responsible largely for our modern civil service, was pragmatic. "This was a 'him or her' situation, and I think this hasn't been brought into focus as much as it should".

More weight needs to be made of the impact of that sermon, she argues. "The general perception is that after the miscarriage" - at the end of January, and apparently a boy - "that was it between Anne and Henry. It wasn't." There was a feeling that Anne was still hugely influential.

A month after Anne's execution, Cromwell admitted to the Spanish ambassador he had plotted the downfall of the Queen. The evidence comes mostly from diplomatic sources, says Alison. "Go back and you can find Cromwell dropping hints about what might happen and how he fears falling from favour with Henry.

"There's a cataclysmic occasion over Easter where it becomes very clear to Cromwell that Anne is recovering her ascendancy; and it's immediately after that he retires from court, pleading illness. It's at that point, on that very date, he decided to take out the Queen. He told the Spanish ambassador."

Anne Boleyn - most probably born at Blickling Hall in Norfolk in about 1501 - was an intriguing character, "though she's hard to know, because it's hard to get beyond that very tragic figure on the scaffold - that very courageous figure - and see this woman who'd been the scandal of Christendom, the catalyst for the Reformation, and in some ways a total bitch!

"I do see her as that in some ways. I never used to; I used to have a very romantic view of her. She was quite vicious towards Katherine of Aragon and her daughter, and she alienated so many people that it must all be true! There were people who were loyal to her. But it dwindled, as she alienated people by the lash of her tongue and histrionics.

"What attracted the king was that she had that indefinable quality we call sex appeal - charisma, charm - which shows itself in one or two of her portraits. We're told her eyes were 'black and beautiful' and 'invited to conversation'. A damn good flirt, I think! And Henry was intrigued because she kept him at arm's length for six, seven years. Which is no mean feat!"

Alison's convinced the Queen didn't have physical affairs while married. "I think the evidence is so overwhelmingly in favour of her innocence that I think it's very unlikely she did."

Her detailed research, she reports, demolished many misapprehensions: proving that the executioner was summoned before Anne's trial; establishing she was not executed on Tower Green, as so many people suppose, but on a scaffold on the tournament ground in front of the House of Ordnance - "I wasn't the first person to say that, but I found more evidence to support it" - and showing that Anne was never imprisoned in the Queen's House at the Tower of London.

While we're about it, what about the legend that Anne's heart was stolen and hidden at the church in Erwarton, outside Ipswich? Almost certainly false, says Alison. She writes in her book about the discovery in the chancel wall, in 1836 or 1837, of a heart-shaped tin casket. It was reburied under the organ. The historian points out that "even today there is a notice in the church stating that it is on record that Anne's heart was buried in there by her uncle, Sir Philip Parker of Erwarton Hall.

"This is all highly unlikely, since heart burial had gone out of fashion in England by the end of the fourteenth century, while the uncle in question was in fact Sir Philip Calthorpe of Erwarton, who was married to Anne's aunt, Amata (or Amy) Boleyn, and died in 1549. Nevertheless, the legend is commemorated in the name of the local inn, the Queen's Head."

An odd vibe... ALISON Weir is coming to the inaugural Lavenham Literary Festival, which runs from November 20 to 22. (Sadly - or happily, if you're an organiser! - her talk is sold out.) She's no stranger to the ancient town ... and reports an odd experience from more than 30 years ago.

"There's a hall-house on the Market Place." She doesn't recall its name, but her description of the location suggests Little Hall, which dates back to the 1390s and more recently came under the umbrella of the Suffolk Building Preservation Trust as a museum.

"I went round on a very hot day in the summer of 1976. I went upstairs and took two steps into this very brilliantly-lit raftered room at the top of the hall and had to walk out. I couldn't stay there. I don't know why. I've never had anything like that happen anywhere else, but it was a really creepy feeling. I've been back since, in the '90s, and didn't feel the same, and I did mention it, but they said no-one else had had the same experience. I can't explain it."

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, U.K., 2010

Ann: Jane Grey and Elizabeth were both apparently amazingly precocious and talented. Do you think they were typical of their age and class?

Alison: Both were formidably intelligent, and were lucky enough to benefit from the kind of classical education that had only recently been extended to girls of the royal family; few aristocratic girls were so lucky, although that was gradually changing, as more parents emulated the royal example.

Ann: Have you considered writing a "what if" novel? For instance if Jane Seymour survived, or Elizabeth married, or if Henry VIII bastard son had survived?

Alison: I already have! In The Lady Elizabeth, I explored what might have happened if the future Elizabeth I had borne Admiral Thomas Seymour a bastard child.

Ann: What factual event that you write about in 'The Lady in the Tower' do you wish never happened?

Alison: One could wish that Anne Boleyn had never been unjustly condemned to death.

Ann: Do you read historical fiction by other authors writing about "your" period, and do you ever contact them if you find an inconsistency?

Alison: I do. My favourite authors of historical novels are Norah Lofts, Hilda Lewis and Anya Seton. And even if they were alive, I would not contact them to point out any errors. Life`s too short!

Ann: Which are your favourite historical characters and why?

Alison: Elizabeth I and Eleanor of Aquitaine - both brilliant, feisty women, and magnificent survivors.

Ann: Do your children read your books?

Alison: Not a chance! I can't compete with Truman Capote and Dr Who!

Ann: Of which book are you most proud?

Alison: The Lady in the Tower: The Fall of Anne Boleyn. It`s my most forensic investigation of a historical subject, and I think it`s my best book.

Ann: If you had to read something outside historical fiction what genre would it be, and what author?

Alison: I enjoy chilling thrillers by authors like Sarah Rayne, S.J. Bolton and Patrick Redmond. I read widely, and have lots of other favourite authors, too many to list here. I`m reading Sleep With Me by Joanna Briscoe right now, for the second time, just to compare it to the TV dramatisation.

Ann: What is the major source for the detail for your books - the everyday things such as clothing and what was eaten?

Alison: Numerous sources. I consult a wide range of books and - dare I say it - the internet, but I'm pretty cautious about the websites I use.

Ann: Which medieval house/site(s) would you recommend to visit and why?

Alison: Barley Hall in York comes to mind, and the Bayleaf Farmhouse at the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum. The Swan at Lavenham. I'm sure there are many others. When you visit these houses, you feel you are back there, in medieval England.

Ann: Have you acquired any medieval items - coins, furniture etc that mean a lot to you?

Alison: I have some coins - that`s all. I do have a lot of reproduction items - a court cupboard, a yeoman`s chair, a settle, painted chests and several tapestries.

Ann: Where do you start your research on an historical figure, and what makes the difference then between a factual and a fictional account?

Alison: I start with my proposal, which outlines the story, flesh it out from general hiatory books, then go to the original sources. After that, I look at secondary sources. I revise and edit all the time. Gradually, a book evolves.

Ann: How many languages did you have to learn to go back to the original sources for your books.

Alison: I read enough French and German to get by, and a little Latin, Italian and Spanish. I use a Latin translator when necessary. Fortunately most sources are available in translation.

Ann: From The Lady in the Tower, I get the impression that Elizabeth was much more like her mother than her father - would you say that was accurate ?

Alison: No, I can see character traits from both parents in her.

Ann: If Anne had had a healthy son, do you think Henry would have stayed with her ?

Alison: Yes, undoubtedly. She`d have been invincible.

Ann: Is there any source material for the Tudors, or earlier, that you know exists, but that you are unable to study ?

Alison: No.

Ann: What is your opinion of the recent TV series about Henry VIII ?

Alison: Compulsive drama, well acted, but a bit of a travesty historically. Good on foreign policy and the convoluted politics of the Divorce, and some of the recreations of the palaces were well done; I noticed that, as the series progressed, they were basing a lot more of the dialogue on original sources, but with that budget, you'd think they'd have taken more care to get it right and not distorted the facts so sensationally. There wasn`t a single female costume that was right for the period! Jonathan Rhys Myers is pretty fit, though, and good in the role, but they should have made him look more like Henry VIII - and aged him! Everyone looks far too young and beautiful. Henry`s tragedy was that he reached the age of 46 - old in those days - before he got a son to succeed him. You don`t get any sense of that in The Tudors.

Ann: What's next in the pipeline ?

Alison: The Captive Queen: A Novel of Eleanor of Aquitaine, out in April. Traitors of the Tower, for Quick Reads (for emergent adult readers), out in March. A biography of Mary Boleyn, for publication in 2010. Two more novels and two more history books!

THE ALLURE OF ANNE

History Today, Vol. 53, No. 5, May 2003

When I was about seven, my father took me on a tour of the Palace of Westminster. I have only the vaguest memories of most of it, but one thing remains clearly in my mind. In the Painted Chamber, I was told to look up at Richard Burchett's Victorian full-length portraits of members of the Tudor dynasty, and I remember distinctly being shown the one of Anne Boleyn (which actually doesn't portray her at all, but Anne of Hungary). I was utterly fascinated to be told that she had had her head cut off.

The moment passed, and my brief awareness of an interest in history remained dormant for the next seven years. At the Westminster Kindergarten and Preparatory School, where I was educated to the age of eight, history had been a succession of stirring tales to enthral a childish mind; even to this day, I still thrill to the epic sweep of great events, the narrative potential in historical happenings - doubtless as a result of my early tutoring. But later, at the City of London School for Girls, I found history dull and uninspiring, a dreary succession of dates, acts and battles. I realised later that it was the personalities, the human aspects of history, that were missing. But of course you only needed facts to pass exams. For me, the ancient Greeks and Romans, the high Middle Ages and even the Tudors passed in a blur of boredom.

As a child, I had been an avid reader, but by the time I moved into the third form at eleven, I had lost interest in books, preferring comics and magazines, much to the despair of my mother. It was not until I was fourteen that I read another book for enjoyment, and that was to prove fateful indeed.

I was off school, suffering from a virus, and had been taken to the doctor, who prescribed a few days at home resting. We had not lived in the area long, and after leaving the surgery, my mother - in yet another attempt to convince me of the pleasures of the written word - took me to the adult library next door to enrol and hopefully choose some books. Wandering around idly, I found one that looked quite intriguing. It was a novel about Katherine of Aragon, the first wife of Henry VIII, and it was entitled Henry's Golden Queen the author was the prolific and exotically-named Lozania Prole.

Recovering at home, I curled up in a chair with the book and read, and read. I could not put it down: I had to know what happened next. A whole new wonderful world was opening before me. I have to admit that it was not just the historical tale that seduced me, but the sex. Of course, this was 1965, and what seemed exceedingly daring then to one who had never read an adult novel would appear very tame now, but I was agog: did people really carry on like that in those days? Why were they so preoccupied with matters that were taboo in the repressed middle-class world of the early sixties?

I had to find out more. By the end of the week, much restored, I was in a local bookshop, urging my delighted mother to buy me three novels by Jean Plaidy. Although I would find them much less to my taste nowadays, I still have those novels on my shelf, tattered and yellowed as they are. For they revealed to me the stories of Anne Boleyn, Katherine Howard, Katherine Parr and Sir Thomas More, and I was enthralled.

By now I was hooked on Tudor history. I progressed to the novels of Margaret Campbell Barnes, Hilda Lewis and Elizabeth Byrd, or anything else I could get my hands on. I haunted the local libraries. My mother obtained for me Jean Plaidy's The Goldsmith's Wife , about 'Jane' Shore, mistress of Edward IV, and thus kick-started my interest in the Middle Ages. Hilda Lewis's Wife to Charles II encompassed the Stuarts. And so it went on from there.

But I was not just reading novels. My new obsession had already led me to the history books and to my first researches into historical facts. While my contemporaries were haunting Carnaby Street and discussing the latest pop records and films, I was beavering away in the school library, becoming familiar with the works of G.M. Trevelyan, A.F. Pollard and A.L. Rowse among many others. My daughter still laughs at me today: 'Mum, you spent the Sixties in a library?' But that was where I wanted to be,

Within a year, I had transcribed my researches on the Tudors into three volumes, which I entitled 'A Study in Splendour', and I had also written a biography of Anne Boleyn based on some original sources and (rather heavily) on Agnes Strickland. It was my dream to own the full set of Strickland�s Lives of the Queens of England, a dream that was not fulfilled until 1995.

Why Anne Boleyn? I was more fascinated by her than by any other historical figure - there is much in Anne Boleyn's story to fascinate anyone. Later, when I came to research her life in depth and from a more mature viewpoint, I realised that I might not particularly like Anne Boleyn as a character, although I have sympathy and admiration for her. Yet the fascination remains. She is a romantic heroine in the truest sense.

By the time I was fifteen, history occupied a large part of my life. I had already begun researching the biographical dictionary of the British monarchy that was to become my first published work, Britain's Royal Families; it would take more than twenty-two years to complete, and be revised eight times over those years before it was ready to go into print. Even now, I could add a great deal to it. Genealogy was then, and still is, a passion. I would sit for hours drawing up royal family trees on rolls of wallpaper, and around 1967, I began collating the pedigrees of the medieval and Tudor peerage, a huge project on which I am still working today. I was never happier than when I was in a reference library, totally absorbed in The Complete Peerage, The Dictionary of National Biography or The Plantagenet Ancestry of Elizabeth of York, to name a few.

I was also writing historical plays: two survive, one on the young Elizabeth I, the other - in the style of a medieval mystery play - on Eleanor of Aquitaine. I would sit out of sight behind a sofa, reading these aloud to my long-suffering family, and putting on the various voices. On one occasion, I staged a play in a model theatre, having drawn and coloured all the cardboard characters, whose costumes I had meticulously researched. I have kept them all.

I had been drawing since I could hold a pencil (I studied Art to A-Level), and not surprisingly the bulk of my creative output at this time was historical portraits, scenes from history and costume sketches. I can hear the weary voice of my art teacher now: 'Not another drawing after Holbein!'

My mother, however, was - and remains - wonderfully supportive. She took me to the Tower of London and to Hampton Court, where she bought me a set of picture postcards of the six wives of Henry VIII, which became my most precious possession at that time, and which I still have. They formed the nucleus of what would evolve into a collection of thousands of royal images, which is still a work in progress today, and which has proved extremely useful for picture research. Back in 1966, my mother also took me to Hever Castle, the home of Anne Boleyn, which remains my favourite historic house. I can remember the excitement when I was presented with the rather expensive guidebook which contained a full page portrait of Anne Boleyn.

It seems amazing, looking back, that reading one historical novel could have led to such an all-encompassing interest in history and, ultimately, to a fulfilling career as a historian and author. But it almost didn't happen. Most of my teachers were unaware of my hours of research in the school library; the reason for this was that I was supposed to be studying for exams in my free periods, so I kept quiet about what I was doing. O-Level History was mind-numbingly boring: I had no interest in British Economic History or the Industrial Revolution - in fact, I had problems staying awake in lessons. As a result, although I passed, my mark was one grade lower than it should have been, and when I applied to take A-Level History on the Tudors and Stuarts, a subject I knew I was well prepared to study, I was - to my horror - turned down. Only those with the top grades were accepted.

The next best thing was an optional general course in history: I was the only sixth former who applied. On the appointed day, I turned up, armed with my biography of Anne Boleyn, and prepared to do battle. The teacher admittedly had every reason to be puzzled as to why this lacklustre pupil had asked to join her course, but when she arrived and I showed her my work, her jaw literally dropped.

Eventually, I did sit the A-Level course, with good results. I also, under that teacher's auspices, completed a biography of Edward III in my spare time.

It is said that everything is more vivid when you are young. Certainly, my exploration, as a teenager, of the world of history, led me on a trail marked out with revelations and excitement. Now, many years later, with my feet planted rather more firmly on the ground and years of serious research behind me, I still feel that thrill of discovery, of losing oneself in another age. My perceptions may have changed, but my love and enthusiasm for my subject has remained constant.

(http://www.historytoday.com/alison-weir/allure-anne)

Alison Weir on the acclaimed play, 'Fallen in Love: The Secret Heart of Anne Boleyn', written by Joanna Carrick and performed by Red Rose Chain in 2012 at Ipswich, the Tower of London, and Hever Castle especially for Alison Weir Tours.

When you watch Fallen in Love, you will see why I am full of praise for it, because every effort has been made to achieve authenticity, right down to the smallest detail of dress. The relationship between Anne and her brother George is portrayed sensitively and movingly. The play is peopled with vivid characters; there may only be two actors, but we remain acutely aware of the progress of history and the world beyond their stage. This is the dramatic depiction of Tudor history at its best.

MISCELLANY

Reader Andrea Wade has an interesting theory that Anne Boleyn may have had a balanced translocation. It is believed that as many as one in 500 people have this. A normal person has 46 chromosomes resulting in 23 pairs. In a person with a balanced translocation a piece of one chromosome breaks off and swaps information with another chromosome. No genetic material is lost or gained and the person is unaffected.

The only problem is reproductively. When a person with a balanced translocation (male or female) sends their genetic information to create an embryo there are a few different possibilities that may occur:

- A normal set of chromosomes is sent from both parents resulting in a normal child.

- One parent sends a normal set and the other their balanced translocation, resulting in a normal child with the same exact balanced translocation as their parent.

- One parent sends a normal set of chromosomes and the other one normal chromosome and one translocated chromosome resulting in a child with an unbalanced translocation.

There are a few possible outcomes for a child with an unbalanced translocation.

- An early miscarriage could occur.

- A late miscarriage of a fetus with disabilities.

- The child could be born with severe disabilities.

A balanced translocation can occur between any set of chromosomes and it is believed that different balanced translocations have different reproductive results. In some women it will present as complete infertility as miscarriages occur very early. Others will carry children with an unbalanced translocation until later in the pregnancy. It is also entirely possible to have healthy children as well. Not all balanced translocations are inherited. They can occur on conception, which means that the parents are not carriers and the balanced translocation is de novo. Andrea's theory is that Anne Boleyn perhaps had a de novo balanced translocation. She became pregnant and successfully conceived a child who had normal chromosomes or inherited her mother's balanced translocation. Anne's subsequent pregnancies ended as a result of unbalanced translocations.

Here's another theory about Anne Boleyn, from reader Sarah Caplan, who has been 'struck by the complexity of Anne Boleyn's personality. I've recently had challenges with 2 people who appear to have something called Narcissistic Personality Disorder, so I've been learning a lot about it. The tricky thing about this personality is that the person can be very high achieving and successful, while also being incredibly dysfunctional on many levels. Here's a quick summary of the traits (found at this website www.halcyon.com/jmashmun/npd/dsm-iv.html): amoral/conscienceless, authoritarian, cares only about appearances, contemptuous, critical of others, cruel, disappointing gift-giver, doesn't recognize own feelings, envious and competitive, feels entitled, flirtatious or seductive, grandiose, hard to have a good time with, hates to live alone, hyper-sensitive to criticism, impulsive, lacks sense of humour, naive, passive, pessimistic, religious, secretive, self-contradictory, stingy, has strange work habits, unusual eating habits and a weird sense of time. Although it's not a historian's place to make a psychological diagnosis, I'm curious to know if you have ever considered that perhaps Anne was suffering from this disorder? In your descriptions of her, she comes across as calculating, ambitious and manipulative. She could whisper in the King's ear and alienate him from his most trusted allies (a trait of the Narcissist). In fact, she was a lot of things that are on the above list! You do point out that she was very generous towards the poor, but when looking at it through the Narcissism lens, perhaps it was only to to make herself look good in the eyes of others? I would think a person does not have to exhibit all the traits listed in order to have the condition. There were moments in Anne's life that did jump out at me as narcissistic, as when she told Henry she had a dream in which Katherine and Mary would have to die in order for her to conceive a boy. The narcissist is an expert at manipulation, dividing people in to camps, and in attaching themselves to a powerful person. That said, one doesn't have to be a narcissist to exhibit narcissistic behavior -- but if she was on the spectrum, perhaps it explains some of her less noble actions.

My response: This is an interesting theory, but I don't think that Anne Boleyn had this disorder. Of course, we cannot know for certain, but it seems to me that her behaviour was in keeping with the circumstances of her life and her rank. Certainly her inner circle had a good time with her, and she had a sense of humour, reportedly revelling in jokes. I think her religious convictions went deep, and her love for her family, which both suggest that she cared for far more than appearances - although that was something that absorbed more or less the entire aristocracy at that time! Anne was not a disappointing gift giver, as the jewel with a maiden tossed in a ship proves (to cite just one example), nor was she naive, passive or stingy. There is no evidence for faddy eating habits or strange time-keeping. The problem is that many of the character traits listed are facets of normal behaviour - and it's also very hard to diagnose medical conditions, especially complex disorders such as this, in historical figures, because their understanding of illness was different from ours, and descriptions of symptoms is often vague.

Not all the graves in the chancel of St Peter ad Vincula were disturbed in 1876, and not all the remains could be identified. That would explain the `absence` of Lady Rochford`s body. It is highly unlikely that Anne`s body was ever removed from the chapel to Salle Church. The best source for the exhumations is Doyne C. Bell`s Notices of Historic Persons Buried in the Tower, but you cannot rely on it entirely for accuracy; I did much background research in order to put the committee`s findings into context. There are a lot of misconceptions about Anne Boleyn`s bones, one of them being that they are in a mass vault in the crypt.

Anne Boleyn may have been Henry VIII's great love - and, some might say, folly - but considering that Henry VIII chose to be buried with Jane Seymour, and that only the banners of Jane and Katherine Parr were carried in his funeral procession, it is unlikely that he would have accounted Anne his favourite wife. It would surely have been Jane Seymour, because she bore him a surviving son. But certainly his greatest and most enduring passion was for Anne Boleyn, although it was a destructive one, souring after marriage.

It was almost unheard of for Henry VIII to question an accused traitor. Anointed sovereigns were not supposed to be tainted by associating with traitors. For this reason, Henry`s personal interrogation of Henry Norris is extraordinary, and seems like a knee-jerk reaction. Once Anne`s infidelity was established in Henry`s mind, he cut off all contact with her.

Thomas Boleyn seems only to have valued success in his children. Even so, when Anne and George faced ruin in 1536, he faced two choices: support them and appear to be condoning their treason, with all the attendant consequences; or condemn them and salvage what was left of his career and his life. His wife was ill, so he may have felt he didn`t have a choice.

I have now established beyond doubt that Anne was never held in the Queen`s House; nor was she executed on Tower Green. She emerged from the Queen`s lodgings into the palace courtyard that lay between the White Tower and Jewel House and the Great Hall, then exited that courtyard through the (long demolished) Coldharbour Gate to the tournament ground (the modern parade ground) where the scaffold stood.

On page 289 of The Lady in the Tower, I cite a scaffold speech by Lady Rochford, and in the Notes and References section give the source as Ellis's Original Letters. Regrettably, there was a mix-up over the numbering of the notes, and the error was picked up too late. The correct source was Gregorio Leti. There is some detailed info on Leti in the 'Notes on Sources' section. One has to approach his work with caution, but in this instance, in view of the other evidence about Lady Rochford, his account seems credible.

The tale about the headsman being delayed on the Dover Road - cited by many writers as the reason for the postponement of Anne Boleyn's execution - originated as pure assumption, and has since been repeated and come to be accepted as fact. There is no contemporary evidence for it.

The post of `graver` of the Tower, held by Henry Norris, was almost certainly a sinecure. It had nothing to do with digging graves! The word then meant an engraver or sculptor, especially in stone, so the office holder probably held responsibility for any stone carving or inscriptions executed in the Tower. Probably he wasn't kept very busy! Thomas Wriothesley, Earl of Southampton, later held the same office.

The Life of Jane Dormer, which states that Anne was 29 when she died, isn't the most reliable source, and it's a late one. As for the letter Anne wrote from Terveuren in 1514, the handwriting is far more mature than that of the young Elizabeth. As Ives and Paget say, the writer must have been in her teens. Furthermore, the Emperor Maximilian stipulated that filles d'honneur at the Habsburg courts should be thirteen years of age and above - they had to be, given what was expected of them. Historians now think that Camden, the source for the 1507 birth date, misread 1501 for 1507, which makes sense, given all the other evidence that Anne was born around 1501.

This 1534 medal of Anne Boleyn was virtually unknown before Eric Ives published the first version of his biography in the 80s. It is the only known contemporary image of her as queen. There is no doubt that the medal is of Anne Boleyn - it bears her motto, 'The Most Happy'. There is no record of Holbein designing any medals, and this one looks too crudely executed to be by him, even taking into account its damaged condition. The image on the medal could well have been based on a portrait, possibly of the Bradford Art Galleries type (right), although presumably there were others, now lost, overpainted or destroyed; for 22 years after her death, no one is likely to have had any painting of her on display.

Through meticulous research, stone carver and scultptor Lucy Churchill has created an authentic replica of the medal of Anne Boleyn, as it would have looked originally (above, left). Copies are for sale through her website at http://www.lucychurchill.com/AnneBoleynMedal.php, where you can read more about her work. A must for anyone interested in Anne Boleyn!

I have speculated a lot about Anne Boleyn's actual birthday in my biography of Mary Boleyn. Roger Powell suggested in his book on royal mistresses that she was born on St Anne's day, and thus named for St Anne, which is possible, as it was a common practice in England before the Reformation to name children after saints. But I have two other theories as to why she was named Anne, although sadly they throw no further light on her birthday! People did not make much fuss about birthdays in the Tudor era. In the whole of the Letters and Papers of Henry VIII there is just one reference to a birthday - to the Battle of Pavia being fought on the Emperor's birthday. Compare this with the lists of gifts at New Year. Not one mention of a birthday gift to Henry VIII or anyone else.

For a long time I was intrigued by a portrait of Anne Boleyn that hung in Ludlow Castle Lodge (below left, detail). Unusually, it shows her three-quarter length. Last year I discovered that it was painted in the early 2000s, by talented artist Paul Workman. I now own the painting, and five other 'Tudor' portraits from Ludlow Castle Lodge.

Anne`s alleged lovers were beheaded publicly on Tower Hill. Sir Thomas Wyatt makes it clear in a poem written soon afterwards that he was watching from the Bell Tower. I checked this against the 1597 pictorial map of the Tower, and it would indeed have been possible to view the execution from there. Chapuys, the Imperial ambassador, says that Anne was made to watch the executions. It is unlikely that she would have been allowed to join Wyatt in the Bell Tower, so either she was watching from another window there, or from a room in the Byward Tower, where Wyatt was held during his imprisonment. These would have been the likeliest vantage points.

The name Boleyn was spelt variously in the sixteenth century, but Anne herself spelt it `Boleyn`, as we do now. Other forms were Bullen, Bulen, Bollain or de Boullant.

In the New York Times and the International Herald Tribune, I was criticised for not mentioning Hilary Mantel's novel Wolf Hall in The Lady in the Tower. I never normally comment on reviews, but in this case I felt moved to do so because Wolf Hall had not been published at the time my book was completed; nevertheless, the books editor at the New York Times still thought I should have mentioned it! But why should a historian mention a novel in a serious history book? Even if it had been possible to write about it, I feel that it would not have been appropriate.