Books

Mary Boleyn: 'The Great and Infamous Whore'/Mary Boleyn: The Mistress of Kings (2011)

Named one of 'The best books of the year' by the Chicago Tribune, Mary Boleyn was also Random House UK's fourth best-selling history paperback in 2012.

"This highly regarded and vastly popular British historian, known especially for her rewarding tilling of the rich soil of Tudor history, turns detective in her latest engaging biography... In answering questions vital to understanding the life of Mary Boleyn, Weir matches her usual professional skills in research and interpretation to her customary felicitous style." (Booklist, U.S.A.)

"Gripping." (The Independent on Sunday)

"This nuanced, smart, and assertive biography reclaims the life of a Tudor matriarch." (Publishers Weekly, U.S.A.)

"A feast for Tudorphiles." (Toronto Globe and Mail)

"Just a quick note about the tour de force that is your Mary Boleyn. Read it in one sitting. I couldn't sleep last night because my mind kept trying to work out the motivations for the various members of the Boleyn tribe. I failed. Your Mary is a fine addition to the Tudor canon." (Carole Richmond, event organiser for Blickling Hall)

"Weir has scoured the sources to produce this intriguing biography... Weir is pioneering a more historiographical form of popular history, without losing her ability to tell a good story." (B.B.C. History Magazine)

“Weir has achieved the enviable skill of blending the necessary forensic and analytical tasks of academia with the passionate engagement that avocational history lovers crave.” (Bookreporter)

“Top-notch... Impressive... This book further proves that [Weir] is a historian of the highest calibre.” (Washington Independent Review of Books)

"Weir chronicles in great detail what is and is not known about Mary Boleyn, and her knowledge of the time period is extensive. She presents the historical evidence and documentation that's available, muses over what it means and draws conclusions. A valid approach to history, to be sure." (St Louis Post-Dispatch)

"Mary Boleyn: The Mistress of Kings shatters the dark cloud that has hovered over Mary Boleyn's name for centuries. I found Weir's arguments about Mary's undeserved reputation strong and convincing. I also enjoyed her speculation on Mary's relationships with her sister and her father. Once again, Alison Weir has written a terrific biography." (www.bookloons.com)

"Weir does her usual splendid job of separating fact from fiction, and dispelling historical myths… [She] does a stellar job of dissecting multiple statements made about Mary Tudor’s behavior and dismisses them based on facts… Weir believes [Mary’s affair with Henry VIII] ended in 1523, when Mary became pregnant—but was her child Henry’s or her husband’s? I will not give a spoiler here, but it is fascinating reading. As my earlier blog attests, I’m a huge fan of Alison Weir’s biographies for the 360-degree view she takes of a subject and the times they lived in. I could not wait to delve into this latest work—and it did not disappoint." (www.thehistorylady.wordpress.com)

Alison Weir provides a fresh look at a much maligned woman. Tudor junkies can get their fix with the most logical scenarios of a woman whose reputation has been tarnished -- to say the least -- by romantic fiction, TV shows and movies, garbled gossip and misconceptions and untruths repeated down through the centuries by historians and others. Using the same kind of extensive forensic research she employed with great effect in The Lady in the Tower, Weir presents in Mary Boleyn a rebooted portrayal of her subject. (Huntington News Network)

"This latest book chronicling the Tudor dynasty is a refreshing change from recent books on the subject. [It] is a well-researched biography, not a novel. Weir debunks many of the rumours that have swirled around Mary Boleyn since the reign of Henry VIII [and] paints a sympathetic picture of a young woman who was swept up by events beyond her control. If you want to learn more about this often-maligned woman of the 16th century, this is a must read." (The Fredericksburg Free-Lance Star)

"As the first full biography of Mary Boleyn, this is a valuable resource both for historians and for casual readers interested in an accurate account of this recently popularised historical figure." (Library Journal)

"Our most detailed view yet of a power behind the throne." (Barnes and Noble)

"Weir states correctly that this book is as much a historiography as it is a biography; she engages and overturns previous presumptions about Anne Boleyn’s older, and ultimately more fortunate, sister. In doing so, Weir not only extricates Mary from the historical description of her as a ‘great and infamous whore’ but aptly demonstrates the prevailing sexual double standards at the Tudor court." (Sara Read, lecturer in English and Society for Renaissance Studies and postdoctoral fellow in the department of English and drama, Loughborough University, in The Times Higher Education magazine)

"[This book] brings together the scattered and often contradictory source material about King Henry VIII’s shadowy mistress. Weir’s informed speculation challenges the popular mythology surrounding Mary including the plot of The Other Boleyn Girl and the longstanding perception that she chose to be a “promiscuous” woman. There is not enough surviving evidence about Mary’s life to provide a full picture of her character and motives but Weir’s analysis places the elusive royal mistress within the vivid settings of the courts of France and England in the sixteenth century." (Carolyn Harris, Royal Historian)

“Weir cuts through the centuries of salacious gossip to present this fascinating portrait of Anne’s elder sister, King Henry VIII’s first Boleyn mistress.” (The Chicago Tribune)

“A refreshing change from recent books on the subject . . . [Weir] paints a sympathetic picture of a young woman who was swept up by events beyond her control. If you want to learn more about this often-maligned woman of the sixteenth century, this is a must-read.” (The Free Lance-Star)

MARY BOLEYN - DEBUNKING THE MYTHS

(William Carey, a lady who might - just possibly - be Mary Boleyn, and Henry VIII)

Everyone knows Henry VIII as the King who married six times; his matrimonial adventures have been a source of enduring fascination for centuries, and the interest shows no sign of abating. But not so much is known about the King`s extra-marital adventures, and it’s clear that most people have the wrong idea about one lady who was briefly his mistress: Mary Boleyn. In recent years, in the wake of Philippa Gregory`s novel The Other Boleyn Girl, and the two films based on it, the public have become fascinated by the story of Mary Boleyn, whose sister Anne was Henry VIII’s second wife. Above all, speculation now rages as to whether Mary’s two children actually were the King`s bastards, rather than the legitimate offspring of her first husband, William Carey. It is a question frequently asked at my book events, and people also want to know if Philippa Gregory’s portrayal of Mary Boleyn is accurate – and it is clear that most of them care very much that it is.

Mary Boleyn was a little more than a footnote to history before The Other Boleyn Girl appeared, but my interest in her dates back to the 1960s, and my original unpublished research on her from the 70s; but when I came to look at her history afresh for my biography, I became aware of many misconceptions and myths that are often accepted as fact, even by historians.

Mary Boleyn represents just one short episode in Henry VIII`s chequered love life. Although he was married for many years to the virtuous Katherine of Aragon, it is clear that he had fleeting affairs in his youth, and by 1514, he had become enamoured of Elizabeth (`Bessie`) Blount, one of his wife`s maids of honour. Their affair lasted for five years, until Bessie bore Henry his only acknowledged bastard, Henry Fitzroy, in 1519. The King then married her off to his ward, Gilbert, Lord Tailboys, and had Fitzroy brought up as a prince, bestowing on him the royal dukedoms of Richmond and Somerset in 1525, and even contemplating settling the succession on him. Meanwhile, Elizabeth Blount had been eclipsed by the woman who was probably her successor in Henry`s bed, Mary Boleyn.

Like her sister Anne, Mary Boleyn had spent some time at the licentious French court, where she seems to have had a brief and discreet affair with King Francis I. It is often said that she acquired a reputation for promiscuity while in France, but there is no good evidence for that. Then she disappears from history for five years. My research suggests that she stayed in France before returning to England to be married, in 1520, to William Carey, Henry VIII`s cousin and an upwardly mobile member of his Privy Chamber.

Mary probably became Henry VIII’s mistress in 1522. We do not know for certain how long their affair lasted. She bore two children, Katherine in 1524 and Henry in 1525, and many now believe that they were the King`s bastards. Against all my expectations, I have found overlooked, compelling evidence that proves their paternity almost conclusively.

Henry VIII’s affair with Mary Boleyn was probably over by the time he began pursuing her sister Anne, and then, in 1527, commenced proceedings to have his marriage to Katherine of Aragon annulled: this was his celebrated – or notorious - `Great Matter`, which would end in the Reformation and the severance of the English Church from that of Rome. That is mostly beyond the scope of my book, but it needs to be mentioned, because Mary Boleyn`s chief historical significance was that her affair with Henry VIII placed him within exactly the same degree of affinity to Anne Boleyn as he insisted that Katherine, his brother`s widow, stood in relation to him. And indeed, that barrier to his marriage to Anne was without doubt the grounds on which their marriage was annulled, two days before Anne was beheaded for treason in 1536.

By then, Mary Boleyn had fallen from favour. William Carey had died in the terrifying sweating sickness epidemic of 1528, and in 1534, in secretly marrying William Stafford, a man far below her in station, Mary incurred the anger of both Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn, who banished her from court. There is no reliable mention of her returning there after that time, and it is unlikely that she and her sister were ever reconciled, or that she was a witness to Anne`s fall; and it seems she only had occasional contact with her motherless niece, the future Elizabeth I – although that contact may have been beneficial to Elizabeth.

It is often said that Mary retired to Rochford Hall in Essex with her new husband, but she did not gain possession of that house until much later, and it seems that she lived abroad for some years. She died in obscurity in 1543. Her children, however, survived to enjoy glittering careers at the court of their cousin, Elizabeth I, and their story forms the final chapter of the book.

I have enjoyed exploring the many grey areas of Mary Boleyn’s life and career: her relationship with parents and siblings; her education; the rather shocking circumstances in which she became Henry’s mistress; where she was and what she was doing in the years in which she barely features in the historical record; and whether there are any authentic portraits of her. Above all, I wanted to discover whether she deserved her promiscuous reputation. Was she used by her family to advance their fortunes, or was she just a girl who liked a good time? What does her life tell us about morality in Renaissance courts and the double standards that prevailed in regard to male and female promiscuity? What did it mean to be the King’s mistress?

Mary Boleyn’s is a tale that has never fully been told, and it is my hope that this biography will add to our understanding of this much–misrepresented lady and her relations with Henry VIII.

Preliminary jacket designs

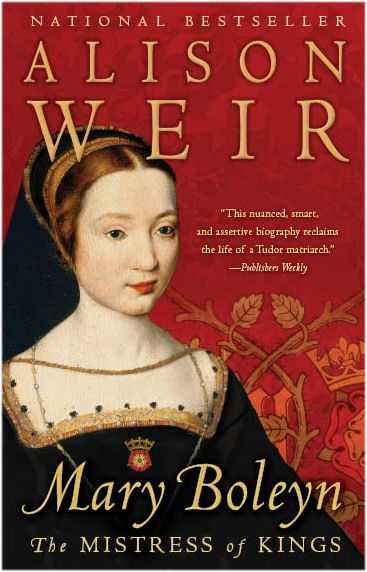

In 2011, there was no authenticated portrait of Mary Boleyn. The portrait on the jackets is probably of Claude de Valois, Queen of France, and it has been photoshopped to alter the colour of the gown and hood. My publishers were informed by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York that it was a portrait of an unknown lady of the French court; they thought that an anonymous sitter would work best for the book, and Mary Boleyn would almost certainly have worn French fashions.

Above: Launching Mary Boleyn in the Great Hall at Hampton Court Palace in 2011

MARY BOLEYN – “THE GREAT AND INFAMOUS WHORE”

by Alison Weir

(An unauthorised version of Alison's original text, below, appeared in The Daily Telegraph in 2011)

Mary Boleyn was the mistress of two kings, Francis I of France and Henry VIII of England, and sister to Anne Boleyn, Henry`s second wife. It was because of his intimacy with Mary that his marriage to Anne was declared invalid. This tangled web of relationships has given rise to rumours and misconceptions that have been embroidered over the centuries, obscuring the truth about Mary. I have never written about a subject who has been so mythologised and misrepresented.

Henry VIII’s amorous adventures have long been a source of enduring fascination and speculation, and the interest shows no sign of abating. In the wake of The Other Boleyn Girl and The Tudors, it has become a global obsession, as one can see reflected in numerous internet sites, where historical personages like Anne Boleyn now have what are virtually fan clubs. It is clear though that many people have a fictionalised perception of Mary Boleyn.

Mary was born between c.1496 and 1500. Her father, Thomas Boleyn, was an ambitious man who was to enjoy a brilliant career at court, and would even prove willing to abet the destruction of two of his children in order to protect his own interests. Her mother, Elizabeth Howard, was widely rumoured to have been Henry’s mistress too, but that calumny probably arose from her being confused with Elizabeth Blount, mother of the King’s bastard son. Yet the gossip was probably believable, as a new reading of a poem by John Skelton suggests she had a reputation for infidelity.

Mary was educated and literate, but no one praised her accomplishments as they did her sister Anne’s, and it might be fair to say that Boleyn preferred Anne and was disappointed in the less-sparkling Mary. Unusually, it was Anne, the younger sister, who was found a place at court first. By then, the charms that were to inspire desire in two kings were blossoming in Mary. It was said she was by far the more beautiful of the Boleyn sisters, but there is no authenticated surviving likeness.

In 1514, she went to France in the train of Henry VIII’s sister, Mary Tudor, who was to marry Louis XII. The French court was one of the greatest cultural centres in Christendom, but licentiousness reigned. Mary Boleyn briefly became the mistress of Louis’ successor, Francis I, who was 'young, mighty, insatiable' and notoriously promiscuous. In 1536, Ridolfo Pio, the Papal Nuncio in Paris, was to report that Francis `knew [Mary] for a very great whore, the most infamous of them all`. Pio was an unreliable source, and as the Pope`s official envoy, he was naturally inclined to vilify the Boleyns, who were blamed for Henry VIII`s break with Rome, but he made it clear that Francis ‘knew’ Mary as a whore, rather than as a maitresse-en-titre. In 1536, Henry VIII was leaning towards France`s enemy, the Emperor, and it was natural for Francis too to disparage the Boleyns. If Mary’s reputation had been that bad, we would have other reports of it – but we don’t. Therefore claims that she became free with her favours and gained a bad reputation are overstated, for there is not a single contemporary reference to support them.

When Mary Tudor returned to England, Anne Boleyn stayed on at the French court. But Mary Boleyn disappears from history for five years. A late sixteenth-century source states that Anne Boleyn was brought up in France at Brie-sous-Forges. But contemporary accounts unanimously state that she remained at the French court for seven years. Was it therefore Mary Boleyn who went to Brie? It would have been easy to confuse the forgotten Mary with her famous sister.

In 1520, Mary married William Carey, one of the privileged gentlemen of the King`s Privy Chamber. He was far more than the obscure, undistinguished courtier described by some historians. He held one of the most coveted positions in the royal household, and was a major player at court. The King highly favoured him, and he seemed set for a brilliant career. Henry VIII attended the wedding, his presence prompted not by an amorous interest in the bride, but because William Carey was his cousin.

It was probably two years later that Mary became Henry’s mistress. In 1522, Henry VIII was thirty-one and in his prime, but married to the ageing and increasingly pious Katherine of Aragon. His affair with Mary was conducted so discreetly that there is no record of when it began or ended. Contrary to popular belief, there was no open scandal at the time. That March, the King participated in a tournament, sporting the motto `She has wounded my heart’. It seems likely that the object of his interest was Mary Boleyn, while the motto suggests that his advances had been repelled. He was the King, handsome, athletic and powerful - an irresistible combination. He probably expected Mary to submit to him without a qualm, but it seems that she didn`t. Maybe her sister was warning her against it – given Anne`s later refusal to become Henry`s mistress, this is a real possibility.

Coincidentally, the first of a series of royal grants to William Carey was made in February 1522. This could have been an award made on William`s own merits; but it could also have been a discreet incentive to William`s wife, with the implicit message that, were she to be kind to the King, he was prepared to be generous in return.

Two days after the tournament, Mary danced in a court pageant, entitled - appropriately - `The Assault on the Castle of Virtue`. Wearing white satin, she had the name ‘Kindness’ embroidered on her headdress; yet she did not go to the King`s bed willingly, for it is credibly stated that Henry `violated` Mary and then kept her as his ‘concubine’. The word `violate` then meant rape or ravishment, so it seems that Mary had very little say in the matter.

The pageant of 1522 was the last occasion on which Mary Boleyn was recorded at court for many years, so secrecy was skilfully maintained. There is no record of Queen Katherine complaining about the affair, nor did she ever make political capital out of it when it would have been in her best interests to do so. Evidently she remained in blissful ignorance.

Mary bore two children: Katherine, in 1524, and Henry, in 1525. It is often claimed that the King was the father, but Henry never acknowledged either child, and it is clear from the grants made to William Carey that Henry Carey was his lawfully begotten heir. Yet I have discovered strong evidence that Katherine Carey was Henry VIII's daughter, notably in a poem written by Sir Philip Sidney for Katherine’s granddaughter. Henry never acknowledged Katherine. He had no need to, as there was a convenient legal presumption that Mary's children were her husband's. And Henry had another illegitimate daughter, Etheldreda, whom he did not acknowledge.

Henry ‘soon tired’ of Mary, and their affair probably ended when she became pregnant in 1523. William Carey died in 1528, leaving her in penury. She appealed in vain to her father for succour. To his credit, the King ordered Boleyn to take her under his roof at Hever Castle. Thereafter, Mary was occasionally at court. She attended Anne Boleyn`s coronation in 1533, and it was perhaps there that she met the man who would become her second husband. Again, she was to court scandal, and this time very publicly. In 1534, Anne, desperate for a son and aware that the King’s passion for her was dying, was horrified when her sister appeared at court noticeably pregnant. Mary now confessed that she had secretly married – for love - plain Mr William Stafford, a younger son of knightly birth with no fortune. Anne was incensed, and persuaded the King immediately to banish the couple from court.

Mary appealed to the influential Thomas Cromwell for help, but not very tactfully. `For well I might a` had a greater man of birth,` she wrote, `but I ensure you I could never a` had one that loved me so well. I had rather beg my bread with him than be the greatest queen christened.` She was never received at court again, and it is unlikely that she and Anne were ever reconciled.

William was a soldier in Calais, and Mary went to live with him there, which explains why there is no mention of her in connection with the cataclysmic fall of the Boleyns in 1536. In 1543, four years after returning to England, she died in peaceful obscurity, happily married to the man she loved – the luckiest of the Boleyns.

ALISON WEIR TALKS ABOUT MARY BOLEYN AND SLUT-SHAMING, SIXTEENTH-CENTURY STYLE

(The Riverfront Times, St Louis, 2011)

If you've read The Other Boleyn Girl (or seen the movie), you probably think you know all about Mary Boleyn, Anne's beautiful, slutty and not-quite-as-bright sister. But the British historian Alison Weir knows way more than you do: She's been acquainted with Mary for nearly forty years, thanks to an abiding interest in Henry VIII and his wives that has produced more than a dozen books, both fiction and non-fiction. A few years ago, she decided that, in order to clear up the many misconceptions about Mary Boleyn's life and lovers, Mary deserved a full-length biography of her own (previously none existed). Mary Boleyn: The Mistress of Kings is out this month, and last week Daily RFT rang up Alison Weir at her home in England and asked some questions for you.

Daily RFT: How hard was it to write a biography of someone about whom virtually nothing is known?

Alison Weir: There's actually quite a lot known about her, but I think she has been misrepresented. The fictional view of her in The Other Boleyn Girl and The Tudors is a romanticized one. I was struck by how different her life was. She has a notorious reputation for being the King's mistress, but during her lifetime she apparently had no reputation at all. We only know of her affairs through later sources. There's endless speculation that the children of her first marriage were fathered by Henry VIII. I've found strong evidence that her daughter was fathered by Henry. You gather fragments of information. As you can't get close to the subject, you have to infer.

It seems like you felt sorry for her.

I did feel very sorry for her. I don't know the circumstances of her affair with Francis I, the King of France, but she was very young and probably had no choice. In regard to her affair with Henry VIII, she was unwilling.

What were the circumstances? She was married at the time, right?

Yes. A treatise accused Henry of "violating" Mary when the affair started, probably in 1522. In the early sixteenth century, "violate" still meant only "rape" or "ravishment." Even if she wasn't technically raped, she was forced into this position by her family and the King. I also felt sorry for her because it was clear the Boleyn family wanted her kept in obscurity. She was a walking impediment to Anne's marriage to Henry VIII. They had what was called an "affinity" because Henry had slept with Mary before he married Anne. It could have been considered incest. Henry received a dispensation to allow his marriage to Anne, but Mary was still a living reminder of that. She was seen as the black sheep of the family and a bit of a failure because she hadn't made her mark. She was an embarrassment because of what she represented and her very existence reminded them she was the means to unseat her sister.

But you're sure Henry was the father of Mary's daughter, Katherine Carey.

You can trace a pattern of Henry maintaining Katherine financially throughout her life, making provision for her to have a good marriage. And this is subjective evidence, but there's a portrait credibly thought to be of Katherine that has a striking resemblance to Henry. I also found evidence in a poem written by Sir Philip Sidney to Katherine's granddaughter in 1582 that makes reference to “hiding royal blood”.

If Sidney knew sixty years later, then wouldn't plenty of other people have known?

It was probably an open secret at court. Queen Elizabeth I did not acknowledge Katherine as her half-sister, but they were very close and Katherine served her devotedly.

Do you have the term "slut shaming" in England? Is that what happened to Mary?

Most writers who tried to portray Mary that way wrote from the nineteenth century onwards. There's no evidence that, at the time, she was publicly shamed. If that were the case, there would be so much more evidence. Henry was actually very prudish. He worked hard to maintain his image of a man of conscience and virtue. He did not parade his mistresses in public until Anne, and he felt that was okay because he planned to marry her. He had quite a few mistresses, quite a lively private life. There's evidence, though, that he was not the most adventurous of lovers.

Well, he was the King. He didn't really have to be, did he?

Of course being the King and so handsome and powerful was a heady combination and many women succumbed without a qualm.

Poor Mary.

Some people say she didn't get anything out of it, in terms of money or position, but she got her rewards afterward. The affair ended probably in 1523. In 1528, Mary's first husband died. She had no home and nowhere to go. The king insisted that her father take her in, even though he didn't want to. Henry had no need to do anything more, but later that same year, he made her an annuity of £100, equivalent to £32,000 today, which was probably for the maintenance of their child.

A lot of Catholic writers blamed the Boleyns for the English Reformation. They seized on any gossip they could find to undermine Queen Elizabeth, like the rumour that Anne Boleyn was raped at the age of seven. They made up scandalous tales.

If you were going to write a novel about Mary, how would you portray her?

I would portray her as jealous of her sister. I think she had a capacity for love, that she was a bit self-obsessed and that she was in the shadow of her siblings. Circumstances made her what she was. In a family where ambition was all, she was a failure. She was treated as though she was of little account. That comes across very clearly. And yet her second husband, William Stafford, mourned her for nine years. It was obviously a happy marriage. As Mary pointed out in a letter to Thomas Cromwell, she would rather beg for her bread with her husband than be the greatest queen ever christened. There's no evidence that she ever met Elizabeth I. I do wonder if they had any kind of relationship. Elizabeth remembered William Stafford from her childhood and was very affectionate with her Carey cousins. She could have had some affection for her aunt Mary. I like to think so.

IN BED WITH… ALISON WEIR’S FAVOURITE BOOKS ABOUT MISTRESSES

Goodreads, 2011

The Goldsmith’s Wife by Jean Plaidy (1950)

This was the first book I ever read about a royal mistress and it captivated me. I find some of Plaidy’s later books formulaic, but this early example tells engagingly the story of ‘Jane’ (Elizabeth) Shore, the ‘merry mistress’ of Edward IV, which is set in late fifteenth-century England. It’s not so much a bawdy tale as a riveting historical drama. It was this book that awakened me to the rich history of this period and to expand my historical research to cover the Wars of the Roses.

Lady of the Sun by F. George Kay (1966)

Dated now, this biography was nevertheless a fine piece of historical detective work, and a brave attempt to reconstruct the life of the notorious, rapacious Alice Perrers, mistress of Edward III in the fourteenth century. It made a tremendous impression on me, as it demonstrated how a historian could take an obscure subject and piece together fragments of information into a credible history. It’s something I’ve since done professionally many times, but Lady of the Sun was a powerful early inspiration. I still have an early manuscript of a novel I based on it.

Katherine by Anya Seton (1954)

Now a classic novel, this was another early inspiration that still enchants me to this day. Anya Seton did with fiction what F. George Kay did with biography – fleshed out a few facts into an epic tale of illicit love and endurance, set against the vivid tapestry of medieval England. The book is a triumph – every sentence is a delight. Researched over four years, it remains a benchmark for historical novels, and one of my all-time favourites.

Painted Ladies: Women at the Court of Charles II – National Portrait Gallery, London and Yale Center for British Art, New Haven (2001)

There have been numerous books on the many mistresses of Charles II, England’s ‘merry monarch’, but this lavishly produced catalogue of portraits features a whole selection of Restoration tarts and beauties, and is packed with fascinating biographies, glorious images, and anecdotes such as this: ‘Pray be civil, good people,’ cried pretty, witty Nell Gwyn to the angry mob surrounding her coach, thinking she was the unpopular Catholic Duchess of Portsmouth; ‘I am the Protestant whore!’ How they cheered.

Bird of Paradise by Sarah Gristwood

Mary Robinson began her career as an actress but soon became the mistress of the future Prince Regent, and was never to live it down. Their brief liaison overshadowed her talents as a writer, poet and early feminist, and blighted her life. This compelling and beautifully written biography explores the tragedy of a woman who was so much more than just a royal mistress.

INTERVIEW FOR THE THAMES VALLEY HISTORY FESTIVAL AT WINDSOR, 2012

You have produced more than a dozen books, both fiction and nonfiction, about Henry and his wives, what was there about Mary Boleyn that you felt needed telling?

It had become clear to me over the years that many people had the wrong idea about Mary Boleyn. I wanted to set the record straight.

What is the one fact about Mary Boleyn that surprises people?

The good evidence that her daughter was fathered by Henry VIII.

What did Mary Boleyn do that had a lasting affect on our history?

Had an affair with Henry VIII! Nothing remarkable in itself, but it created a barrier to his marriage to her sister Anne and undermined his case for an annulment of his marriage to his brother’s widow.

A lot of Catholic writers wanted to blame the Boleyns for the English Reformation are they right to?

To a degree. The Boleyns were very influential evangelicals, and they supported the Reformation legislation. But they were not Lutherans; Anne died a devout Catholic, and probably Mary did too.

Mary’s second husband, William Stafford, mourned her for nine years. It was obviously a happy marriage. Does it matter whether she was happy?

I should hope so! Although happy stories don’t always make for riveting reading. I don’t think her earlier life had been easy, so it’s heartening to think she did find happiness, and maybe she welcomed the obscurity.

Did she get on with Elizabeth?

We don’t know. There is no record of her having any dealings with her. But Elizabeth recalled knowing William Stafford at court in her youth, and she was very close to her Carey cousins, Mary’s children, so maybe she did hold her aunt in some affection.

Henry VIII was actually very prudish. He worked hard to maintain his image of a man of conscience and virtue? Is this Mary Boleyn’s saving grace or the reason for her obscurity?

It was her saving grace in that Henry’s insistence on discretion saved her reputation from being ruined. But the Boleyns were aware of the impediment that her affair with him had created, and that it had the potential to undermine Anne’s marriage to him and the legitimacy of her daughter Elizabeth, and it appears that they relegated Mary very much to the background.

Was the woman revealed by your research the same woman you expected to find going in?

No. I thought her promiscuous and notorious because of it, but the evidence suggests the opposite. I don’t think she had much choice.

Do you like her, what is it you like about her or her role in history?

I don’t think there is enough evidence on which to base an opinion; I was just fascinated to uncover the truth about a woman who was a footnote to history until she became mythologised in fiction and films.

I am asking this of every author in the Festival: what do you think history has to offer us?

The benefit of experience. We can always learn from the past.

Thank you for your time, we are very much looking forward to seeing you at the Thames Valley History Festival, what can we expect?

New insights into the life of a royal mistress, and into how historical sources can be used to reveal the truth.

What makes your event special, unique or controversial?

No one had researched Mary Boleyn in depth before I wrote my biography, and I was able to draw some surprising – and possibly controversial - conclusions, which I look forward to sharing with my audience.

Do you like doing events, and if so what do you like about them most?

I love doing events because they give me a chance to engage with others who share my passion for history.

MARY BOLEYN ON FILM

Mary Boleyn has been portrayed several times in films and T.V. dramas. She is seen in the film 'Anne of the Thousand Days' (1969), played by Valerie Gearon (left). Clare Cameron made a cameo appearance as Mary in Granada TV’s 'Henry VIII' (2003), with Ray Winstone playing Henry VIII. That same year the BBC made a TV movie of Philippa Gregory’s novel, The Other Boleyn Girl, starring Natasha McElhone (left centre). In the film version of The Other Boleyn Girl (2008) Scarlett Johansson plated Mary. In the TV series 'The Tudors' (2007-2010) Perdita Weeks (right) appears as Mary in six of the thirty-eight episodes.

Charity Wakefield played Mary Boleyn in the B.B.C.'s TV series, 'Wolf Hall'.

MARY TUDOR: THE WHITE QUEEN

Unsubmitted book proposal by Alison Weir

This is the story of Mary Tudor – not `Bloody` Mary, but her aunt, Henry VIII`s sister: the exquisite Mary, who became Queen of France and then Duchess of Suffolk, and who was also the grandmother of Lady Jane Grey. Mary Boleyn served in Mary Tudor’s household in France, so readers might like to know a little more about the life of the woman who is sometimes referred to as ‘the White Queen’.

Born in 1495, the fifth of the seven children of Henry VII by Elizabeth of York, Mary spent her happy childhood under the dominance of the King`s mother, the Lady Margaret Beaufort. As with her siblings, her father regarded her as a political pawn whom he could one day use to make a politically advantageous marriage alliance, and at the age of twelve, Mary was betrothed to the Archduke Charles of Habsburg, the future Emperor Charles V. A glorious future appeared to be ahead of her…

A year later, Henry VII died and was succeeded by Mary`s surviving brother, Henry VIII, who was five years her senior. She was fond of him, and he of her – he would name his great ship, The Mary Rose, in her honour - although, contrary to popular misconception, her name was not Mary Rose! Mary became close to Henry's first wife, Katherine of Aragon, and as the years passed, she grew into a stunning beauty, admired by all, and took her place at the centre of the glittering Tudor court.

Then, unheedingly, she fell in love. The man in question was Charles Brandon, Duke of Suffolk, an ambitious and handsome nobleman eleven years her senior, who was not only the King`s greatest friend but also his double in looks. Undoubtedly Brandon loved Mary, but as the son of a standard bearer and only recently elevated to the peerage, he could not look to marry the King`s sister. Apart from the fact that he was married already, and in fact had made a bigamous second marriage when he already had a wife, Mary was betrothed to the Archduke Charles.

Mary and Brandon kept their love a secret. If Henry guessed what was going on, he made little of it, perhaps dismissing it as infatuation or mere flirtation. But then, in 1514, when Mary was eighteen and `a paradise`, as one ambassador described her, Henry’s alliance with the Habsburgs ended in acrimony, and he turned to France, their rival. To cement this new friendship, he proposed that Mary should become the third wife of the ageing and ailing Louis XII.

In vain did Mary protest against being forced into this union. But Henry took no notice, and lavish preparations for the wedding went ahead. At length, as brother and sister said a tearful farewell on the quayside at Dover, Mary wrested from Henry a promise that, if Louis died, she might then marry the man of her choice. And with that she had to be content.

Louis was delighted with his bride, and after their wedding night boasted that he had crossed the river three times. His courtiers observed that he had certainly looked very uncomfortable, and secret observers were of the opinion that the King could never father a child. Mary bore his attentions so patiently and well that Louis pronounced himself more than satisfied with his bride. However, he died within three months, on New Year`s Day 1515.

By tradition, French queens spent the first forty days of their widowhood in seclusion, shrouded in white weeds and veils – hence the name `the White Queen`. This was to ensure that the paternity of any child that the widowed queen might be expecting remained unchallenged. Mary chafed against the confines of her gloomy, black-hung chambers, but her solitude was relieved by the visits of the new King of France, the young, lecherous and married Francis I, who soon began making amorous moves towards her, and suggesting marriages that would keep her in France, within his reach – marriages that would not be to Henry VIII’s advantage. Alarmed for her reputation, Mary wrote to her brother, begging to come home.

And soon, one glorious day, there he was – Charles Brandon, her beloved – waiting in the outer chamber, sent by Henry to escort her to England. The attraction between them was more powerful than ever: they could not resist each other. Mary told Charles of Henry`s promise, and eventually he let her persuade him that they should marry. They wed in secret and joyfully consummated their union while still in France. It was only then that Brandon began to worry that he had acted rather too precipitately…

He wrote to Cardinal Wolsey, Henry`s chief minister, confessing what he had done. The resulting pyrotechnics reverberated from Greenwich to Paris. Henry was furious, incandescent. His promise to Mary forgotten, he had been planning a new political marriage for her. And Brandon, his closest friend… how could he have done such a thing? The word traitor was uttered, more than once, and the lovers` situation looked ugly.

At length, after heated exchanges of letters, much pleading and begging on the part of the miscreant pair, and the cunning machinations of the Cardinal, Henry forgave Mary and Charles – on condition that they paid an enormous fine that was to cripple their finances and curtail their social activities for many years to come. But at last they were allowed to return to England, where Henry staged a public wedding ceremony for them in May 1515.

After that, Mary bore two sons who died young, and two daughters. The elder, Frances, would marry Henry Grey, Marquess of Dorset and become the mother of the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey. Mary would not live to see that. Her relationship with Charles soured in the 1520s, with the emergence of Anne Boleyn, Queen Katherine`s rival for the King`s affections. Mary sided with Katherine, Charles with Henry and Anne. There were too the constant reminders of Charles`s previous marriages, and Mary`s ever-present fear that her union with him was no true marriage.

It was a sad decline, a tragic ending for a woman whose beauty and vibrancy had been the toast of Europe. Mary died, probably of cancer, in June 1533, aged 37, virtually estranged from her brother the King and little-mourned by her husband, who married his son`s fourteen-year-old betrothed within weeks.

Mary`s story is the subject of two important biographies: Mary Tudor: The White Queen by Walter C. Richardson (1970) and Sisters to the King by Maria Perry (1998). It was told in novel form more than thirty years ago by Jean Plaidy in Mary, Queen of France and by Hilda Lewis in Rose of England and Heart of a Rose.

ALISON WEIR IN CORRESPONDENCE WITH JOSEPHINE WILKINSON

Josephine is the author of Mary Boleyn (2009). What follows are extracts of historical interest from an extensive exchange of emails.

J: I have just discovered, through your web site, that you have completed your new book, Mary Boleyn: “The Great and Infamous Whore” and that it is being prepared for publication. Mary Boleyn is such an interesting character as you know. I would like to take the opportunity to wish you all the best with it and to say how much I look forward to reading it.

A: That is so generous of you, especially if - as I suspect - you are the author of Mary Boleyn, which I much enjoyed. That book came out when I was working on mine, and it was the last text I looked at when completing my research. It is mentioned in my introduction in the book. What prompted me to write it was a growing awareness of misconceptions about Mary. I wonder if you came from the same direction - if it is you! What are you working on now?

J: You are correct - I am indeed the author of the other Mary Boleyn. I did not really consider writing about Mary until my editor twisted my arm! He was very persuasive and convinced me to write a short biography of Mary, and it made a nice change from Richard III, the first volume of whose biography I had just published. I agree with you about the misconceptions about Mary. As I worked on my book I quickly learned that there was much more about her than could be squeezed into a 50,000 word MS, but my editor was adamant that I should stick to my brief. In the event, it has turned out to be one of the best-selling books he has ever been involved with. I am so glad you enjoyed it, and I thank you for saying so; I know yours will do exceptionally well. May I say, too, how much I enjoyed your The Lady in the Tower? It is a fantastic piece of scholarship.

At the moment I am working on a Princes in the Tower book. I was supposed to be doing the second volume of my Richard III biography, but I kept getting stuck. I knew I would not be able to move forward until I had resolved the problem of the two Princes, which is pivotal to an understanding of Richard, so I pitched the idea of a Princes book to my publisher; luckily, he was open to the idea! Have you a new project waiting in the wings, or is it too early yet?

A: I have all your books, but haven’t yet had a chance to read the one on Richard III. I too have written on the Princes in the Tower, many years ago, so it will be interesting to see if you arrive at similar conclusions. I am not surprised that Mary Boleyn has sold well. I hesitated in my first email to comment on the length and the large type, but that was something that really struck me, because by the time I came to read it, I knew there was much more to the subject. I can tell from the text that you are a serious historian - I am at one with you on many points, even though we diverge in some aspects - and I am horrified to hear that you were constrained by that word limit, because the impression that such a short book gives is that you couldn’t find any more to say. That’s so unfair to you as a historian, because obviously you could. I am really glad that the book sold well, which makes up for it to some extent. Thank you so much for your very kind words about The Lady in the Tower. My next non-fiction project is the lives of England’s medieval queens; I’m also working on a sequel to my novel Innocent Traitor.

J: I’ve got a copy of your Princes book; strangely enough, I bought it at Middleham Castle while I was doing research there. As with Mary Boleyn, there are many points of agreement and some divergence, but I think that is normal, healthy and to be expected when two historians work on the same subject. They say that books are dialogue, so long may it continue, I think. Your next project sounds intriguing. Which is your favourite queen?

A: Thanks again for your very kind words. I agree with you about history books: each is a contribution to an ongoing dialogue, and sometimes you find that you want to revise what you wrote some years ago. Certainly that is what I have found with Mary Boleyn, because my biography will render redundant much of what I said about her in earlier books. It was the same with Anne Boleyn. The important thing is to remain objective. It’s a fact too that two historians can study the same sources and come up with completely different conclusions - and never more so than with the Princes in the Tower. It’s the one book on which I don’t give talks, because too many people seem to be incapable of approaching the subject objectively. I’m sure you are discovering that!

My favourite medieval queen has to be Eleanor of Aquitaine - I’ve written two books on her. Fiction is a different discipline, and it’s been a learning curve for me. I’m getting there. I enjoy it now, but the editing process is very different, which I found daunting at first.

J: I can understand why you don’t give talks on the Princes. I used to maintain a small page on the Goodreads web site but I closed it down because too many people from the Richard III Society would contact me to tell me what I should be writing about Richard! People tend to be very subjective, but, as historians, we can only say what the sources allow us to say. I was warned by a former colleague that writing about the Princes was very dangerous. Very often we read enough about someone to be able to include them in another’s story and to show their place in it, but not in such depth as to allow us to really know them. I don’t think revising what we have previously said about a figure is bad scholarship or sloppy work, but it is a sign of maturity and natural development within the discipline.

Eleanor is a fascinating queen; I’m also attracted to Isabella, Edward II’s queen, and her intrigues with Roger Mortimer.

I read with great interest about the ghost stories and legends about Anne Boleyn in your book. I must say I love ghost stories. Did you know there is a tradition about Anne here at York as well? Close to where I live is the King’s Manor which, as you know, was visited by Henry VIII. Many people have encountered the ghost of a woman wearing a green dress in the Tudor style and carrying fresh roses (other version say she is carrying blood-red ribbons). Some people say she is Anne Boleyn and that her ghost is linked with the execution of Lord Percy on Pavement at the foot of the Shambles. The problem is that it is the wrong Percy and there is no record, as far as I know, of Anne ever having visited York. I would be more inclined to agree with those who say that the ghost at King’s Manor is Katherine Howard, who did come here with Henry, King’s Manor being one of the probable settings for a tryst with Thomas Culpeper.

A: I’m fascinated by ghosts too. I’d heard of the King’s Manor ghost, and maybe – if there are such things - it could well be Katherine Howard, as there is no evidence that Anne Boleyn ever visited York. I’ve done ghost walks in York, which were great fun. I’m doing an event at Blickling Hall on 19th May with Tracy Borman, and I’ll also be giving a talk on the ghost legends about Anne. Then there’ll be another ghost talk and a midnight ghost hunt. Can’t wait!

J: The evening at Blickling sounds wonderful!

Can you believe it, of all the ghosts in York, I’ve got the cat! I sometimes see it slinking out of my bedroom, I heard its voice once as well. I don’t mind it, though, and it doesn’t seem too bothered that I’m a dog person at heart.

A: My publishers prefer me to write about strong, feisty women - so goodness knows why I ended up writing about Mary Boleyn! My problem is occasionally having to do a hard sell on a subject to my U.S. publishers, when my U.K. publishers are happy to go with it. It took me eighteen months to persuade them to agree to my doing Katherine Swynford. They said no one in America had heard of her, or John of Gaunt! Not true!

J: I’m glad you were able to write about Katherine Swynford; hers is a great story. I think people are interested in these characters once they know about them and their connections. One woman I would like to write about is Katherine Howard, who interests me a great deal. I’m interested in Elizabeth of York as well, she’s attractive in her own right, but it’s her men who also interest me, especially Prince Arthur.

Would you ever write about Cecily Neville and Margaret Beaufort? The Tudor family are great to read about, I love The Tudor Dynasty by Griffiths and Thomas.

A: I have to confess that I’ve been commissioned to write a book about Katherine Howard’s fall, although I won’t be starting work on it for two years. I have a novel and my queens book to write first, and so far I’ve only typed up four pages of the bibliography! I wanted to write about Elizabeth of York, Cecily Neville and Margaret Beaufort, but I’ve steered clear of them all because Sarah Gristwood is writing about all three. Have you got the recent book on Prince Arthur, edited by Steven Gunn and Linda Monckton?

J: That’s great news about your book about Katherine Howard’s fall - will you be taking the same approach as you did for your Anne Boleyn one? Even though Katherine’s biography has been done a few times, I think the full story of her fall has still to be told. I’ll steer clear of Elizabeth of York as well if Sarah Gristwood is doing her. I do know the book you mentioned about Prince Arthur, and I plan to buy it at some point. About four years ago, when I was resident scholar at St Deiniol’s Library, I took a long weekend and went to Ludlow. I wanted to see the castle and the town, and I knew Richard had spent part of his childhood there. In spite of that, the strongest ‘impression’ I got was of Arthur. I am intrigued by him. I spent the morning of my birthday at the castle - it was a lovely misty, autumn day (there’s a photograph of it in my Richard book) and, probably because of the weather, I had the castle to myself.

A: Yes, I plan to take the same forensic approach with Katherine Howard as I did with Anne Boleyn. I agree, the full story of Katherine’s fall has not yet been told. It’s only recently that scholars have been able to quote the sources frankly. There are several grey areas that I want to look at closely: did Katherine actually commit adultery? What happened to Manox? Was Katherine being blackmailed? We may never know the answers for certain, but I don’t think that the subject has been studied as extensively as it should be.

Ludlow is beautiful. I too think of Arthur when I am there. I proposed a book on him and Katherine, but my publishers weren’t keen. Sad!

I’ve started my novel, and am busy delving into the life of Katherine Grey. I have a sub-plot about the Princes, told from the perspective of Richard III’s daughter, Katherine Plantagenet. I thought it would be interesting to look at Richard from his daughter’s point of view.

A historian friend and I have a friendly argument going on about Richard III. I, as you know, think that Richard was responsible for the murder of the Princes. She dares (!) to contest that, but has not reached a firm conclusion yet. Really keen to know your view, if you are allowed to share it!

J: One thing (among many) that I find intriguing about Katherine Howard is the possibility that she was ‘married’ to Francis Dereham in a pre-contract, and that it had not been dissolved when she married Henry. I get the feeling that Cranmer was trying to steer her into admitting this, which might have saved her life. If that had been the case, the possibility of blackmail is all the greater. There is much to be discovered and assessed.

I might try to propose a book about Arthur at some point - if we keep at it, they might give in! I think he is important enough to warrant a book.

It’s exciting that you’ve started your novel - and the idea of looking at Richard from his daughter’s perspective is inspired. I mentioned her in my biography and speculated about whom her mother might have been.

Did Richard murder the Princes - I’ve been warned that this question, whichever way I answer it, will herald the end of my career! If nothing else, my book will advance the debate, and I know it won’t be the last word on the subject!

A: I agree with you about Katherine Howard: a precontract before witnesses was as binding as a marriage, and the existence of one would indeed have saved her, but the silly girl kept denying it. I discussed all this in my Six Wives book many years ago, but didn’t have the scope to explore it further. Getting excited about the project now, but have to wait another three years before I get started on it.

Now that Giles Tremlett has published his excellent Katherine of Aragon, I think it will be a while before I could decently propose a book on her and Arthur. That collection of academic essays is excellent, but it’s not a biography.

I thought someone had tentatively identified Katherine Plantagenet’s mother - I did a few preliminary notes for my novel last year, and I discovered her identity then. I must look them out. Haven’t got to that part of the book yet.

Well, you know my views on the Princes!! I looked at the possibility of their survival when researching my own book, and was not convinced. If Edward V died of natural causes, why didn’t Richard say so, instead of maintaining silence in the face of the damaging rumours? But I will rest my case until I read your book. I like to keep an open mind. I do wish people could be less subjective about Richard III!!

J: I think, in defence of Katherine Howard, she was probably very frightened and unable to think straight about what Cranmer wanted her to say. There was also the spectre of Anne Boleyn hovering over her. I feel sorry for her, poor girl.

I do know your views on Richard and the Princes! - but I also respect them. I feel there is room for every viewpoint in the debate and, unlike those members of the Richard III Society, I prefer to take an objective view. Having said that, their subjectivity is part of their mission statement, which is to rehabilitate Richard’s reputation. That’s fine, as long as it isn’t at the cost of the truth, whatever it might turn out to be. It does Richard no favours to try to turn him into a saint. I much prefer him as a man, with all the flaws and virtues that entails. One member of the society took me to task for suggesting that at least one of Richard’s illegitimate children was conceived after his marriage to Anne Neville. As far as I see it, Edward II, Richard II and Henry VII are the only kings of England who didn’t have mistresses. Actually, I’m not sure about Henry, it might be interesting to see what I could find out.

A: I agree with you about Katherine Howard. I’m looking forward to delving into this further. Last year I got hold of a recent privately published book on her, which the author had spent a lifetime researching. It’s called Men of Power: Court Intrigue in the Life of Catherine Howard by Elisabeth Wheeler (2008). She cites numerous original sources, and pursues the line that Katherine was not so much an adulterous queen as the victim of a reformist plot. I haven’t read it yet, but I’m interested to see what evidence Wheeler presents for a theory that isn’t new but hasn’t yet been properly studied.

I admire your objective approach. That came across in Mary Boleyn. One can’t just decide something, like ‘Richard is innocent’, and then make the facts fit, as some people do! Henry VII is supposed to have had a bastard son, Roland de Velville, conceived before his marriage - but I haven’t looked at the sources for years.

J: I must get hold of Elisabeth Wheeler’s book on Katherine Howard. I found her website, and the book looks very interesting. It’s a pity she published it privately; maybe a reputable publisher will pick up on it at some stage and it will be available to more people.

I published a book on Anne Boleyn called The Early Loves of Anne Boleyn, which covers her years before she met Henry. I agreed to it because I wanted to explore her men - James Butler, Henry Percy and Thomas Wyatt. Unfortunately, the same restraint was imposed - no more than 50,000 words. Once again, I knew I had something that could have been much better, had I been given the space and the time to do it. I also edited a new version of Paul Friedmann’s fantastic Anne Boleyn. This was published under ‘P. Friedmann’ to disguise the fact that the author is a man, as though people wouldn’t buy an Anne Boleyn book unless it’s by a female author!

Roland de Velville rings a bell. Henry was also supposed to marry someone called Maud at one stage, although I haven’t gone into this in any depth at all. I’ve a friend and former colleague at Glasgow University who studies Henry VII and greatly admires him. He was very surprised when I told him I didn’t think he had murdered the Princes, as some people assume.

I was looking at the information about your Mary Boleyn book on your web site - it looks amazing, I can’t wait for it to come out!

A: I have your book The Early Loves of Anne Boleyn. I also have your edition of Friedmann’s Anne Boleyn, which was a very timely and useful - and handsome - publication, as it came out when I was researching The Lady in the Tower. As for people not buying books on Anne written by men, what about Eric Ives? David Starkey? David Loades? George Bernard?

Wasn’t Henry Tudor supposed to marry Maud Herbert, the daughter of his guardian?

Thanks for your kind words about Mary Boleyn!

J: All those male authors you mention are wonderful. Have you read George Bernard’s new one? I’ve been reading his articles over the years, so it was inevitable he should write his theories up in a book. I found it very enjoyable. I was particularly intrigued about the reassessment of some of Anne’s portraits that is going on at the moment, the theory being that they might actually be Mary Tudor, and that the ‘B’ on the necklace stands for Brandon. Having said that, there is a resemblance between the lady in those portraits and the portrait of the older Anne that you use in your book. It would be difficult to believe they were not the same woman.

A: George Bernard is very entertaining, and such a maverick. I have been amused at his sparring with Eric Ives in the academic journals. They start off so nicely, and then the knives come out.

I haven’t seen anything about the reassessment of Anne’s portraits, and after studying them for 45 years, it seems quite astonishing that anyone should question the identity of the sitter in the NPG portrait type, of which so many versions exist that clearly she was very important and there was widespread demand for a portrait of her. Why would there be a demand for so many portraits of Mary Tudor? We know too that Anne favoured initial pendants, as her daughter Elizabeth can be seen wearing an A pendant in the Henry VIII family group at Hampton Court. The resemblance between the NPG type and the 1534 medal and the Chequers ring, plus the fact that most of the NPG-type portraits have various Latin legends bearing Anne Boleyn’s name makes the identification almost certain.

There is a superficial similarity between the NPG type and Mary Tudor in her wedding portraits, but Mary looks rather different in other portraits that show her red hair, which looks quite dark in the marriage portraits. I just looked at that and rather did a double-take, because you can see how people might think it was Anne in that portrait. It even led me to wondering if it could be Anne and Henry in that picture. I know that Mary was at the French court, but I’ve always thought that the costume wasn’t right for 1515. Of course, one version has the ‘Cloth of gold’ verse on it - but when was that added? And could the verse apply the other way round, referring to Anne’s mercer ancestor? Is the orb symbolic of her queenship? You have set me thinking! I am going to do a little delving later...

I began writing up my study of those portraits earlier this year, but of course have had little time in which to get very far with it. Right now I'm writing the book I’ve always wanted to write - my medieval queens project, so I consider myself very lucky! I’m beginning with my 1970s bibliography - it’s a museum piece in itself, as the primary sources were all published in the 19th century, many in the Rolls series. It made me realise how much scholarship has been undertaken since. I’ve never read a book on writing. Just read history books and hoped for the best! I used to transcribe all my research by hand, in huge files with pages assembled in chronological date order, and another file for additional info, such as biographical details of all the people, info about places, the court, heraldry, genealogy; then I had to draw up a timeline in order to write the skeleton outline of each chapter and then add in the research, editing and amending all the time.

Now, thanks to Sarah Gristwood’s advice, I just write the outline, which is effectively my book proposal (of one to three pages), then add in the research as above, working on the book as a whole. It is far more efficient, and quicker, as you can see what you’ve written already and evaluate new info against that. Also, you never have that dread feeling that you have to write the book after completing the research. It’s there, evolving as you research. Maybe you already do it this way, but I hope this helps if you don’t. Of course, you have to do a very careful read-over at the end, to check that everything is consistent.

J: George Bernard mentions a paper by Brett Dolman, given at Hampton Court in 2009, and called ‘Tudor Regal Portraiture: identity, uncertainty and interpretation’. He also says that the NPG portrait of Anne was due to be reassessed this year as part of the Making Art in Tudor Britain project. This project is on the NPG web site, but there’s no mention of the Anne Boleyn portrait. Bernard’s discussion of Anne’s portraits is on pp.196-200 of Fatal Attractions. His sparring with Eric Ives is entertaining, it reminds me of the altercation between Markham and Gairdner about Henry VII, Markham thought he had murdered the Princes, but Gairdner disagreed.

Your description of your working method is very useful. Mine is somewhat similar, or at least it is evolving that way. I do most of my work in long-hand then type it up. More recently I have begun to take the whole-book approach that you mention - putting things in the appropriate place as my research progresses, rather than working in a strict chronological order. I keep track of it all by using the ‘tracking changes’ bubbles, which I find very useful for marking up areas where inconsistencies might arise.

Do let me know what you come up with regarding Anne’s portraits. It certainly is intriguing.

A: I know about Brett Dolman’s paper. He asked to meet up with me beforehand, as he knew I had made a study of Tudor portraits, and wanted to discuss his proposed talk. We had a date arranged, but I had to cancel as something urgent came up. I wish now that I’d been able to go! Maybe he’s thought better of reassessing Anne’s portrait. He might well have set himself up for a host of emails from outraged art experts and historians!! I had the same response when I suggested - and only suggested - that Anne Boleyn might have been pregnant at the time of her execution. Some contemporary evidence appeared to indicate that, and my publishers got very excited about the publicity it would generate, but the fallout was startling. I had John Guy on the phone, David Starkey writing articles, other historians being quoted in the press... I’ve distanced myself from the theory now, but not as a result of the reaction: I just looked at the evidence again when researching The Lady in the Tower, and decided it really wasn’t sufficient to support the theory - although there do remain unanswered questions.

J: I didn’t realise you’d done a study of Tudor portraits - did you publish it, or would you consider doing so? I think it would be an interesting book. Perhaps, as you say, Brett Dolman decided not to reassess Anne’s portrait, although it would be interesting to see what he might have come up with. Historians mainly seem satisfied with the current identification, but it’s always worth revisiting them, just to be sure. I was convinced by David Starkey’s identification of the portrait, usually said to be Thomas Boleyn, as James Butler. There is no correlation between that one and the image on Thomas Boleyn’s tomb - which I think does share some similarities with Anne’s portraits. It is possible to believe the two are father and daughter. I hope you get a chance to look into the portraits soon.

It’s a fascinating theory that Anne might have been pregnant at the time of her execution. I know you’ve rejected it now, but it does make sense - if they suspected she was carrying a child. It would explain why they examined Lady Jane Grey prior to her execution, just to be sure she wasn’t pregnant. Having said that, they don’t appear to have taken the same precaution with Katherine Howard, but maybe they reasoned that, if she had been pregnant, the baby probably wouldn’t be Henry’s, so wouldn’t be worth saving.

A: I’ve got reams of research on these portraits, gathered over the years, and an extensive library of books on Tudor portraiture. The project is only in its early stages, so it doesn’t yet reflect the scope of the study. I’ve done a lot of research on the portrait said to be of Mary Boleyn - as you’ll know, the most famous version (of about six) is at Hever - and I can’t find anything to support the identification as Mary. In fact, a good case can be made for it being a lady of the royal House.

You’ve answered the unspoken question about Anne being pregnant. Whoever the father, the law decreed that a condemned woman who was pregnant would - at least temporarily - be spared execution, because her unborn child had committed no crime. That was why Lady Jane Grey was examined on the morning of her death. How awful that must have been for her. There is, as you say, no record of Anne Boleyn or Katherine Howard being examined, although maybe we just have no record of it. Not all of Kingston’s letters survive.

J: Your work on the portraits - it really is a huge project, but so absorbing. Will you use the one of William Carey in your book? I thought he looked charming.

You are right to draw attention to all the ambassadorial despatches and letters. Thank goodness for Eustache Chapuis is all I can say. I find him fascinating and would love to do some work on him. Who says men don’t gossip! What I find particularly attractive about him was his care for Queen Katherine and Mary, and the fact that he held a small private service for Katherine after her death because he felt her proper status hadn’t been acknowledged in her official funeral.

It is true, as you say, that not all of Kingston’s letters have survived, which is a great shame. We could have learned so much more. I really feel for Lady Jane Grey, the Victorian depiction of her execution seems to capture all the sadness and horror of her last moments.

Talking of innocents and not executing those who had committed no crime, I couldn’t help thinking of Thomas More’s beard. While he was in prison he had no one to look after him, so his beard grew quite long. As he laid his head on the block he lifted his beard out of the way, saying that it should not suffer because it had not offended the king. His sense of humour is amazing, and one of the most attractive things about him.

A: I’ve written a whole appendix on the subject of portraits of Mary Boleyn and William Carey. The fact that there are at least six versions of the ‘Mary’ portrait indicates that there was demand for a portrait of the sitter, and she is wearing ermine, a fur restricted to the upper nobility and royalty. So I suspect, given the proliferation of the image, that the sitter was royal. Anyway, the costume is that of the mid-1530s. There would not have been any demand for Mary at that time, given that she was little known and in disgrace (and probably living abroad) from 1534. The sitter bears no resemblance to portraits of Anne Boleyn, Jane Seymour or Margaret Douglas. She is too young to be Mary Tudor, who died in 1533. Could this be Frances Brandon? A wedding portrait from 1533? There is a resemblance in the nose to Charles Brandon in his ‘marriage’ portrait (yes, I think it is him, having done some digging last night, although I think it’s later than 1515/16.) Even so, that doesn’t quite explain the demand for pictures of Frances - she wasn’t that well known either! It would help if we could identify any clue or reference in the pendant or brooch, or the flowers, but they are too indistinct. What do you make of this?

J: Did you find William Carey an interesting figure? I felt very sad for him when I wrote about his death, I feel he could have made more of a mark on history - nothing major, just a temporarily important and intriguing figure lurking in the background, a bit like the Exeters.

There does appear to be some resemblance between the ‘Mary’ portrait and Frances Brandon. I suppose, as Lady Jane Grey’s mother, images of her might have been in demand for a time. I think she also looks a bit like Margaret Tudor, although Margaret would be too old by the time this portrait was painted - might they have flattered her, perhaps? The flowers would be a big help if we could make out what they were, but it is difficult to tell what they are. If they were bitter herbs of some kind, they could identify her as a Mary, but I might have expected her to have worn more pearls if she were a Margaret. I don’t suppose she was one of Jane Seymour’s sisters, or sister-in law...? I’ll have a good think about this!

A: I’m with you on William Carey, I have no doubt he would have had a brilliant career ahead of him if he hadn’t died young. He was clearly one of Henry’s most favoured courtiers, and he was his cousin too. I agree that his portrait (the Irish version) shows him to have been very good looking. I think, with David Starkey, that the original could well have been an early work by Holbein.

I don’t think there would have been much demand for portraits of Frances, as Jane was queen for just nine days. Yet she is the likeliest sitter. The problem is, no one has properly studied the Hever portrait type, which was called Anne in the seventeenth century. To me, it looks as if it dates from the seventeenth century. I don’t have scans of all the versions: I’d like to compare the ones at Henden Manor and Southside House (the latter isn’t an original), but it would need analysis to determine which of the six, if any, is an original. One of the two in the Royal Collection may be; I haven’t seen the other. I haven’t even been able to discover the location of one of the versions; I just have a scan from a ‘private collection’. Yes, she does look a little like Margaret Tudor, but she’s too young, as you say. Keep thinking!!

J: The thing I like most about William Carey is the dreamy look on his face as he sits with his book, his place marked with his finger. I think it is so sweet. He looks to be completely absorbed in musing over what he has just read. I try to imagine what kind of book it is. It’s tempting to think he might have been among the clique of young poets, like Wyatt, Surrey and George Boleyn, although nothing remains of his work if he was. That he might have been painted by Holbein shows how important he could have become, I think. Other men who interest me are the ones who died with Anne. I read as much as I can about them in your Lady in the Tower and in ODNB, and they are fascinating. There is much to know about William Brereton, who seems to have been a very hard man. I’m especially taken with gentle Mr Norris; the anecdotes about him in Cavendish are charming. It was wonderful that you managed to track down that portrait said to be of Francis Weston, it’s nice to have some idea of what at least one of them looked like. Has it been more positively identified?

I will keep thinking about our mystery lady. Clearly it cannot be Mary Boleyn because she had little status in the mid-1530s, especially since she had married ‘beneath’ her. She would not have been noble enough to wear ermine after that. It would be nice to know what she looked like, though. I think she’s a great character. Did you enjoy working on your book about her?

A: Yes, I think there was much more to William Carey than the popular view of him would suggest. The chances are that he was part of that poetic circle at court. I’d had my thoughts about the portrait of Weston at Parham for ages, but did some background research on it for The Lady in the Tower, and it can only be Sir Francis, on costume alone. No other contemporary fits the description of Mr Weston of Sutton Place. They had had no idea about his identity at Parham, and were very excited to discover who he was. I too find Norris a likeable character, and would like to see a full study made of his life. I think that, if Anne Boleyn had had any feelings for any of her alleged lovers, it would have been for Norris, although I don’t believe for a moment that they were ever lovers.

J: Do you think it would be possible to do a full study of Henry Norris? I’m not sure what sources would be available, apart from the obvious ones. It would be nice to do it, though. I’d also like to tackle Jane Seymour, and I find Jane Parker also needs a better treatment than she has had, I have always found her intriguing.

A: Yes, I think there would be enough on Henry Norris to justify a biography. He was at the centre of affairs for years before his dramatic fall. I wrote a biography of Jane Seymour myself in the 80s, but it wasn’t very long (it was based on a section of my original MS. of Six Wives, which runs to 1024 pages that are not double-spaced but actually contain transcriptions from every source I could lay my hands on, so it’s very useful for research). What more is there to say or know about her? I don’t find her a very sympathetic character.

J: I agree that Jane Seymour is not a very sympathetic character. That said, I think she’s interesting enough to read about. I think the fact that Henry Norris was so much a favourite of the king makes his fall all the more tragic. Of course, it was terrible for them all, but there is something very attractive and romantic about Mr Norris. He had quite a bit of power at the court as well.

I’ve been giving our mystery lady some thought - could she be Gertrude Blount?

A: Gertrude Blount? Not sure why there would be a demand for at least six portraits of her in the mid-1530s, when she was out of royal favour? And I think she’d have been in her mid-30s by then - too old to be this sitter. I wish someone would have the paintings analysed. The Hever version was called Anne Boleyn in the seventeenth century, according to one source I read, but that may not be accurate, as something in the painting of the face suggests to me that that version was painted in the eighteenth century. One of the Meade-Waldos, who owned Hever after the Waldegraves, emailed me with scans of royal portraits owned by his family, which had originally hung at Hever, but he wanted advice in identifying them, so maybe he wouldn’t be able to help. I met Lucy Whittaker, curator of the Royal Collection. She said they have two versions of the portrait, and she agrees that the sitter cannot be Mary Boleyn. It may be that, at a later date, someone mislabelled one version as Mary Boleyn, and the error was repeated, leading to a proliferation of later copies. In that case, it could well be Frances Brandon or even Katherine Willoughby, Duchess of Suffolk. The plot thickens!

I did some research, for my novel, on Katherine Haute, whom you and Michael Hicks (I think) have tentatively identified as the mother of John of Gloucester and Katherine Plantagenet. I think that’s a sound theory, so I delved deeper. As you’ll know, she was the wife of James Haute, youngest son of William Haute by Joan Wydeville. Genealogies describe him as being of Waltham, Kent, but documents in the National Archives show that he held lands in Herts. and Beds., his chief seat being the manor of Kinsbourne Hall (or Annable’s) at Harpenden, which he bought from William Annable soon after 1467. The site of the house lies to the east of the surviving Tudor (with later additions) manor house, Annables House, at Kinbourne Green.

James Haute died before 20th July 1508, when his will was proved. A court roll dating from the early 16th century refers to ‘silver and stuffs, etc. at my house in my wife’s custody’. So Katherine was alive then. Although Kinbourne Hall remained in his family until 1555, James leased it to a Thomas Bray in 1506, and I wonder if he did that because his wife had died and he no longer wanted to live there. Pure speculation, of course. I couldn’t find a copy of the will, which might tell us more. There were two sons of the marriage, Edward Haute of London, who was his father’s executor in 1512 and his heir (he d.1528) and Alan.

Richard Haute, James’s brother, was an associate of Gloucester. It seems that his attitude towards the Wydeville affinity was complex!

J: I see your point about Gertrude Blount. It’s interesting that someone thought our mystery lady was Anne Boleyn. Your idea that someone had mislabelled the portrait makes sense, and of course that would become fixed in peoples’ minds, especially with all the romance surrounding the Boleyns. The possibility of it being Katherine Willoughby hadn’t crossed my mind, but it an interesting theory, and it brings us back to the Brandons.