The Six Wives of Henry VIII (1991)

THE SIX WIVES OF HENRY VIII is Penguin Random House UK's biggest-selling e-book ever.

"At last we have the truth about Henry VIII`s wives. This book is as reliable and scholarly as it is readable, and, thank goodness, it is unpartisan. It does justice to these very different ladies." (A.L. Rowse, The Evening Standard)

"The wives of England's greatest monarch were as varied as they were many, as this compelling biography reveals... Alison Weir has a wonderful way of bringing them and history alive. A joy to read from cover to cover." (Manchester Evening News)

"How well she brings these six unfortunate ladies to life." (Daily Express)

"Enthralling... The panorama of royal family life as it meshed with politics, dynastic needs and history is rich, vivid and convincing�Gripping." (Chicago Tribune)

"This book is not a turgid history manual, but a highly readable account." (Daily Mail)

"Brilliantly written and meticulously researched. Alison Weir is adept at bringing to life these historical figures." (San Francisco Chronicle)

"The story of England`s second Tudor monarch and his rather sordid married life has been told often. But never has it been told as well. Alison Weir has combined impeccable research and a first-rate literary tone... [She] has given us an entertaining work that combines the accessibility of a popular history with the highest standards of a scholarly thesis." (Detroit News)

"Well researched and... beautifully written... This work unquestionably is the finest exercise in collective biography focusing on Henry`s wives." (Library Journal)

"Weir's incomparable book... will enthral even the most casual general reader. The author devoted years to researtching this brilliant volume... An exquisite treatment, sure to become a classic." (Booklist)

"You will devour it in one sitting." (The Good Book Guide)

"An entertaining account,... full of interesting detail... Alison Weir`s treatment of this perennially fascinating subject is a beguiling one." (Anne Somerset, The Literary Review)

"Vividly recreates the Tudor court." (The Bookseller)

"A page-turner guaranteed to keep you up well past bedtime." (The Topeka-Capitol Journal)

"As usual, Alison Weir has uncovered a wealth of fascinating detail." (Birmingham Post)

"This is a riveting account for which the author is to be congratulated... for her dedication in researching and collating such a wealth of material, and for producing a model for all historians - a text that combines the easy readability of popular history with the highest standards of scholarship." (Huddersfield Daily Examiner)

"This book is a highly readable partisan account,... a work of sound and often brilliant scholarship." (OK World, Tulsa)

"This book has all the drama, romance, political intrigue and vengeance of a best-selling thriller. It is an entertaining and highly readable account." (Wiltshire Gazette and Herald)

"The six queens and the monarch they married come vividly alive for us." (Follansbee Review)

"The scope and depth of Weir's research provides a wealth of detail missing from many other narrative histories about the Tudors." (Publishers Weekly)

"Meticulously researched and eminently readable." (Postscript)

"The story of Henry's wives has been told many times, but Alisin Weir makes a lively tale of it without becoming simplistic or sentimental." (The Irish Times)

"Alison Weir's hugely readable composite biography looks inside the tense manoeuvrings of the Tudor court to bring sux very different women to life.' (Waterstone's Books Quarterly)

I was delighted when this book, published in 1991, returned the the New York Times bestseller lists 24 years later!

FROM BOOK OF THE MONTH CLUB 1992:

The popular British sport of royal-family watching was born in the reign of Henry VIII, the most powerful and most marrying monarch Britain has ever known. Henry gave his subjects plenty to gossip about: political and sexual intrigues, charges of incest and adultery, two divorces, two beheadings, countless dalliances and six wives - all fascinating women because of who they were as well as what happened to them.

Henry's first wife was his brother's widow, Kather-ine of Aragon. Though beloved by the people, she faced two insuperable obstacles: no royal son and Anne Boleyn. The fiery, ambitious Anne, who refused to be seduced until she became his royal consort, was Henry's grand passion. But his five-year battle to get rid of Katherine and make Anne Boleyn his lawful wedded wife not only changed the course of history and laid the foundation of the Church of England, it also changed Henry's character. From a dashing young Renaissance ruler, he degenerated into a ruthless, corpulent tyrant. The story of Henry and Anne began with passion and ended with a bloody death. Every consort who followed feared the same fate.

After his unhappy experience with Anne, Henry made his most successful marriage. The new queen was Jane Seymour, a strong-minded matriarch-in-the-making who gave her husband his male heir but died in the process. Henry's fourth marriage to Anne of Cleves was arranged from a portrait. When he met her in the flesh, he recoiled in disgust and never consummated their marriage. Next came Anne Boleyn's foolish cousin, Katherine Howard, whose indiscreet love affairs brought her the same fate as her cousin. The last was Katherine Parr, an intelligent, demure widow who eased the king's remaining years and happily outlived him.

Alison Weir's brilliantly entertaining story of life at the Tudor court under each of Henry's wives is already winning rave reviews both in England and here at Book-of-the-Month Club. "At last we have the truth about Henry VIII's wives," wrote A.L. Rowse in The Evening Standard. "I adored this book," B.O.M.C. Editor Michelle Slung said. "There is simply no other way to put it."

INTERVIEW WITH KARLEEN TAUSZIK, 2015

Sharing e-pub news and interviews with bestselling

e-format authors at KidsEBookBestsellers.com

On Saturday I saw that your e-book, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, hit the number 1 spot in the Teen section of the Barnes and Noble Nook store. Congratulations on your achievement! In a few sentences, tell us what your book is about.

It's the story of the six queens of the Tudor monarch, Henry VIII. It's set in a court dominated by the will of an egomaniacal, suggestible king, and the power politics and ruthlessness that were the reality behind its magnificent façade. It tells how Henry's six wives lived a hair's breadth away from disaster - and how it frequently overtook them. Theirs are grim and tragic stories, set in a lost world of splendour and brutality: a world in which love, or the game of it, dominated, but dynastic pressures overrode any romantic considerations. In this world, one dominated by religious change, there are few saints.

Tell us briefly about your path to publication: Traditional or independent? Recently or further in the past?

I went down the traditional route with mainstream publishers. I was first published in 1989, and since then I have clocked up 17 non-fiction history books and 5 historical novels.

What top factors do you believe put your e-book where it is now?

I think that the story of Henry VIII's queens has a compelling, undying fascination.

How are people finding out about your book? Tell us about your marketing and use of social media.

Through my publishers' marketing and publicity strategies. I post regularly on Facebook and sometimes on Twitter and Pinterest, but I see my website as my main point of contact with readers.

What is your target audience, and how do you believe the e-format works for that audience and serves their needs?

I have a broad target audience, as attendances at my many events show - from children younger than 9 to seniors over 90! Both sexes too.

What were your initial thoughts about e-publishing? Was it your idea or your publisher's? Were you hesitant? Excited? Apprehensive? Optimistic? Fill in the blank? Have those initial thoughts changed now that you've done it?

It was my publishers' idea to republish my books in this format. I'm delighted about sales, of course, but e-books are not for me personally!

What does your writing schedule look like? What are you working on now?

I'm writing a novel about Katherine of Aragon, the first in a series of six about the wives of Henry VIII. I've also been commissioned to write four non-fiction history books, so I'm going to be very busy over the next few years!

Time to pull out your Magic 8 Ball: How do you see the world of e-publishing developing for children and young adults over the next 5 years? Do you think it will ever exceed or replace print publishing?

I sincerely hope not!

Do you believe the e-format helps or hurts your readers, specifically children and/or young adults? How?

I don't believe that children should be brought up expecting to have everything delivered electronically. I speak from experience, as the mother of two children, one with special needs. They are adults now, and both read e-books. but if I was bringing them up now, I would want them to experience the pleasure of traditional books.

EDITOR'S BOOK CHOICE, From Tapestry, the magazine for Friends of Hampton Court Palace, Winter 2004/5

Alison Weir, author of books on The Princes in the Tower, Elizabeth the Queen, Mary, Queen of Scots, and Britain's Royal Families, comes to speak to the Friends of Hampton Court Palace in November. Her best-selling book The Six Wives of Henry VIII has recently been reprinted and provides a series of detailed and highly readable mini-biographies of each of the wives. Here we have proud but misguided Katherine of Aragon, ambitious and vengeful Anne Boleyn, the strong-minded Jane Seymour, then on to the good-humoured Anne of Cleves, empty-headed Katherine Howard, and finally the 'godly matron' Katherine Parr.

All bar one of Henrys queens, according to Alison, were 'old' for marriage. Only Katherine Howard was still in her teens, the others were in their twenties or thirties when they married King Henry, at a time when marriages were more commonly contracted at 14 or 15 years of age. But in common with other queens of England, they were 'housewives on a grand scale', with nominal charge of vast households and far-flung estates, and Henry was content to leave almost all the domestic decision-making to them.

It's often forgotten that Katherine of Aragon was Henry's queen for over half of his reign (24 years in all), whereas most of her successors enjoyed their position on the throne beside Henry for a matter of a few years or even months. Katherine was a popular queen, with deeply-held religious principles, and 'set a high moral tone for her household'. Unusually for the time, she was literate, well-read and versed in the scriptures.

Anne Boleyn, on the other hand, was something of an enigma. As the author points out, most of what we know about her comes from the last days of her life, when she was incarcerated in the Tower awaiting execution. To the Protestants, this reforming queen was a saint and a martyr, but to the Catholics Anne was a she-devil who had exercised an evil influence over the King. The story of her relationship with Henry 'began with passion and ended with a bloody death.'

It was Jane Seymour that Henry truly loved, and as his Queen she exercised a fresh, positive, influence on him. Jane was an admirer of Katherine of Aragon and worked to reinstate Katherine's daughter Mary at court. Strong-willed and determined, Jane was nonetheless obedient to her husband, sharing his broadly conservative views on religion. As a result, Alison believes, Henry genuinely loved and respected her.

Married by treaty without having met her, Henry's union with Anne of Cleves was doomed from the start. Fortunately for Henry he was able to annul the marriage on the grounds that it was not possible to consummate it (he found her repellent!). Despite, or perhaps because of, her rejection, Anne of Cleves emerged as 'the wisest... and the luckiest' of Henry's six wives. Not so fortunate was Katherine Howard, a victim of political skulduggery whose marriage was promoted by one faction at court, the Catholics, and denounced by another, the reformists.

Katherine Parr was a widow - married twice before - and came from a respected gentry family from the North of England. But unknown to Henry, she was a secret Protestant, and after her marriage to the King she worked stealthily to encourage him in a reformist direction. But she was careful to avoid the charge of heresy, and became a friend to both the Catholic Princess Mary and the Protestant Princess Elizabeth. Katherine outlived Henry by just one year, marrying Thomas Seymour soon after the King's death, and bearing him a daughter (named Mary, after Henry's daughter) before dying as the Queen Dowager.

Many of the key events described in Alison's book occurred at Hampton Court. Prince Edward was born here, and christened in a midnight ceremony in the Chapel Royal. Less happily, much of the plotting and scheming of the rival factions that vied for influence over the King took place at Hampton Court too. And it was in this Palace, according to legend, that Katherine Howard tried to interrupt the King at his prayers to plead for her life; her ghost is still said to haunt the palace corridors.

The author provides a very helpful chronology and several appendices, including family trees charting the genealogy of each of Henry's wives, and a comprehensive bibliography for those thirsting for more knowledge on this subject. This is an excellent book and well worth buying. (Reviewed by Andy Smith)

Above: original portrait by Paul Workman, and detail, from Alison Weir's own collection, formerly at Ludlow Castle Lodge. When this portrait was painted, in 2002, the portrait on which it was based was still thought to be Katherine of Aragon. Recent research strongly suggests that it portrays Mary Tudor, sister of Henry VIII.

For anyone who reads Spanish, here in the link to an interview I did for El Mundo in January 2015 when I was speaking at Peterborough Cathedral for the annual commemoration of Katherine of Aragon: qtadralhttp://www.elmundo.es/cultura/2015/02/08/54d6620422601d443c8b4581.html

PETERBOROUGH CATHEDRAL: KATHERINE OF ARAGON'S BURIAL PLACE

An abbey was first established at Peterborough (originally called Medeshamstede) in 655 AD, but it was largely destroyed by Viking raiders in 870. In the mid-10th century a Benedictine abbey was created from what remained, with a larger church and more extensive buildings. The church survived until an accidental fire swept through it in 1116. The present building was begun in 1118 and consecrated in 1238, and its structure remains essentially as it was on completion. The original wooden ceiling, completed between 1230 and 1250, survives in the nave, the only one of its type in this country and one of only four wooden ceilings of this period surviving in the whole of Europe. It has been over-painted twice, but retains its original style and pattern.

In 1539, during the Dissolution of the Monasteries, the great abbey of Peterborough was closed and its lands and properties confiscated by King Henry VIII. However to increase his control over the church in this area he created a new bishop and Peterborough Abbey became a Cathedral.

Two queens were famously buried in the Cathedral during the Tudor period. The grave of Katherine of Aragon, who died in 1536, is in the North Aisle near the High Altar, while Mary Queen of Scots was buried in 1587 on the opposite side of the altar. Her grave is now empty, as she was re-buried in Westminster Abbey in 1612.

Visitors to Britain's cathedrals are accustomed to seeing memorials to nobility and royalty, but it is rare to find monuments to people of a more humble background. This is not the case in Peterborough, where a gravedigger by the name of "Old Scarlett" is something of a local folk hero. Robert Scarlett died in 1594 at the age of 98, having spent much of his life as the sexton at Peterborough Cathedral. Not only does his memory live on in a portrait above the great West door of the 12th Century cathedral, but he also enjoys the honour of having a Peterborough pub, the "Old Scarlett", named after him. Legend suggests that he may have been the inspiration for the gravedigger in Shakespeare's Hamlet. That is pure speculation, but there is no doubt about his main claim to fame -- that during his long career he buried two queens in the cathedral: Katherine of Aragon and Mary, Queen of Scots.

The cathedral was vandalized during the English Civil War. Almost all the stained glass was destroyed, and the altar and reredos [reerdos] were demolished, as were the cloisters and Lady Chapel. Some of the damage was repaired during the 17th and 18th centuries. In 1883, extensive restoration work began, with the interior pillars, the choir and the west front being completely rebuilt. In the 1960s new figures were added to the West Front and in the 1970s the spectacular hanging cross was added to the nave. Since a disastrous fire in 2001 a massive cleaning and restoration program has been undertaken.

Peterborough Cathedral is an outstanding example of Norman architecture - a national icon and the foremost jewel in the city's crown.

IS THIS KATHERINE HOWARD?

This beautiful portrait (left) of a young woman aged seventeen, from Holbein's workshop, is in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York. It is in poor condition and the face has been overpainted. There have been unsubstantiated claims that the sitter is Katherine Howard; certainly her rich costume marks her out as belonging to the highest ranks of society. She wears a French hood and a black silk gown with a natural waistline, a low square neck and wide sleeves slashed with red. Her pendant is of gold with pendant pearls, and on her bodice is pinned an elaborate cameo brooch. Traditionally her costume has been dated to 1540 or later, because wide sleeves like these are seen in a portrait of around that date, probably of Katherine Howard, by Hans Holbein, at Toledo, Ohio (right). This is clearly not the same sitter.

However, dendrochronology has dated the wood panel to 1522, and copies of Holbein portraits were usually executed on new wood. Thus it is possible that the portrait was painted before 1540. The costume is essentially French: the French hood is of a type seen in French portraits in the 1520s and 30s, and in Holbein's front-facing drawings of ladies of Anne Boleyn's chamber, executed around 1533-6. By 1540 fashionable waistlines had begun to drop in the front to a point below the waist, as is clear in the Toledo portrait. Prior to that they had been girdled at the natural waistline, as in the New York portrait. The full, puffed sleeves are unusual in English costume; they are seen with aiglets in the Toledo portrait, and in a portrait of Katherine Parr of c.1545 in the National Portrait Gallery, but are otherwise rare. Yet they appear frequently in French costume from at least 1518. The pendant is similar to the one in the Toledo portrait of Katherine Howard (which can be better seen in the National Portrait Gallery version), but it is clearly not the same one. Thus there is nothing to link the New York portrait to Katherine Howard.

MY HEROINE: KATHERINE OF ARAGON

Article from B.B.C. History Magazine, August 2001

If I were to name the one historical personage whom I most admire and who has influenced me greatly, it would be Katherine of Aragon, first wife of Henry VIII, King of England. I admire her character so much that I named my daughter after her.

Katherine was born in 1485, the youngest daughter of the Spanish sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella. Piously reared and carefully educated, she was married at sixteen to Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales, eldest son of Henry VII of England. Tragically, he died six months after the wedding. Katherine declared she was still a virgin, and the Pope issued a dispensation for her marriage to Arthur's younger brother, the future Henry VIII. For various political reasons, Henry VII would not allow the wedding to take place, but after his accession in 1509, the young Henry chivalrously married his Spanish princess, who was nearly six years his senior.

As royal marriages went, that of Henry and Katherine was initially highly sucessful: there was love and respect between them, they shared the same intellectual interests and religious faith, and both enjoyed presiding over the most magnificent court in Christendom. Henry was not always faithful, but he was discreet, and Katherine soon learned to shut her eyes to his casual infidelities. One thing really marred the royal couple's happiness, and that was their failure to produce a son and heir. Out of six pregnancies, only one daughter, the Princess Mary, survived. In an age that believed it was unnatural for a female to wield dominion over men, this was a dynastic disaster.

By 1522, Henry had begun to convince himself that his lack of a son was divine punishment for his having married his brother's widow. After he fell in love with Anne Boleyn, his wife's maid-of-honour, around 1526, his doubts crystallised into certainty, and he petitioned

the Pope for an annulIment. However, the Pope was then in thrall to Katherine's nephew, the powerful Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, and dared not grant Henry's wish. After six frustrating years of tortuous and ultimately fruitless negotiations, the King broke with Rome, founded the Church of England, and had Archbishop Thomas Cranmer dissolve his union with Katherine. He had already secretly married Anne Boleyn.

Throughout these momentous years, Katherine stood firm in the belief that she was the King's wife and that their marriage was indissoluble. She refused to free him by entering a nunnery because she had no vocation. She declared she would give her blood to protect the rights of her beloved daughter. As a result, humiliation after humiliation was heaped upon her. In 1531, the King sent her from court and separated her from the Princess Mary: she never saw either him or her child again. Shunted from house to house, in increasing poverty, hounded by threats from Anne Boleyn, continually wounded by Henry's actions, and in advancing ill health, Katherine remained steadfast to her principles. Just before she died, of cancer of the heart, on 7th January, 1536, she sent the King a farewell letter, which ended with the poignant words, 'Lastly I make this vow, that mine eyes desire you above all things'. Then, still defiant, she signed it with the title of which she had long since been deprived, 'Katherine the Queen'.*

I first came across Katherine of Aragon when, at the age of 14, I read a rather lurid historical novel entitled Henry's Golden Queen. Lurid it may have been, but it drove me to the history books to find out the truth about Henry and his wives, and thus, in the now oudated pages of Agnes Strickland, Garrett Mattingley and Mary M. Luke, was born my life-long love of history. I admire Katherine greatly because she was a woman of principle who remained true to her beliefs through prosperity and adversity. Her devotion to her husband and daughter shines forth as a beacon in an age characterised by self-seeking and political pragmatism. There can be no doubt of her sincerity, or her piety. My own mother possesses similar qualities, which I try to emulate, and this may be one of the reasons why I account Katherine as one of my chief heroines. I realise that, at the dawn of the 21st century, many of Katherine's virtues might be regarded as unfashionable and politically incorrect, but she remains a person whose strength and moral courage we can all respect. Even Henry VIII, who first loved her, and later became infuriated by her, had to admit as much.

* The authenticity of this letter has since been questioned, and it has been dismissed as part of the Catholic hagiography of Katherine of Aragon, yet it appears in Lord Herbert of Cherbury's biography, and he was no Catholic apologist, and had access to documents lost to us, so I see no reason to doubt Katherine's authorship. The mundane details in the letter would surely not have featured in a forgery.

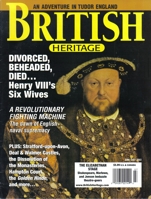

HENRY'S QUEENS

British Heritage, June/July 2002

It is fair to assume that, if Katherine of Aragon had borne a son, Henry VIII would not now be remembered as the most-married monarch in English history. When the 17-year-old Henry married his elder brother's 23-year-old widow in June 1509, few could have predicted that the failure of this union would lead to a revolution in both Church and State. Katherine was pretty, intelligent, even erudite, pious and charming - and, above all, she was of high royal blood, being the daughter of Ferdinand and Isabella of Spain. This marriage alliance, and the international recognition it brought with it, was important to the prestige of the recently established (some said parvenu) Tudor dynasty, and in every way Katherine seemed a most suitable wife for the young King.

Henry VIII, imbued with the ideals of chivalry, proved an ardent and attentive husband. Tall, slim, and handsome, with red hair and an athletic physique, he was a magnificent prize in the marriage market, and there is no doubt that Katherine quickly succumbed to his charms. Her dignified gravity was the perfect counterfoil to his ebullient boisterousness, and together they presided over the most splendid court England had ever seen. They lived their lives in "continual festival" in a whirl of tournaments, pageants, masques, hunting, hawking, dancing, music-making, gambling, and feasting. Together they shared a passion for learning and theology, and their court was virtually a university that welcomed the finest minds of the age.

The birth of Prince Henry in 1511 seemed to set the seal on the King's contentment, yet the baby died six weeks later. Two more sons died at birth before Katherine bore a living child, a daughter Mary, in 1516. Another daughter died young in 1518. By 1524, the Queen was past child-bearing age, and Henry ceased having sexual relations with her. His lack of a son to succeed him boded ill for the future security of his dynasty; if he died without a male heir, civil war would almost certainly follow. In an age when it was deemed unnatural for a woman to wield dominion over men, it seemed unthinkable that the Princess Mary should succeed her father.

Katherine had faded into the background of Henry's life by 1522. He still paid her every courtesy and undoubtedly retained an affection for her, but he had for some time taken his pleasure with ladies of the court; in 1519 Elizabeth Blount had borne him a son, Henry Fitzroy, and he was now involved in a liaison with Mary Boleyn. It was not long before the King questioned the validity of his marriage to his brother's widow, having read in the Bible that such unions were unlawful and would be punished with childlessness.

Henry's doubts crystallized in 1526, when he fell in love with Anne Boleyn, Mary's younger sister. Anne had been educated at the French court and was very French in her ways. She set fashion trends and bewitched suitor after suitor with her eyes, which were "black and beautiful" and "invited to conversation." There is little doubt that she had learned other ways of pleasing men at the French court, for the King later revealed that she had been corrupted there in youth. Yet when Henry began laying siege to her questionable virtue, she held him off and would go on doing so for seven long years.

Anne Boleyn was ruthlessly ambitious. Very early on in her relationship with the King, she set her sights on a crown and never lost sight of her goal. Flattered and importuned by courtiers who perceived her growing influence, she became the centre of a faction dedicated to gaining power. When, in 1527, the King applied to the Pope for an annulment of his marriage, Anne was the driving force.

The Pope, in thrall to Katherine's nephew, the Emperor Charles V, stood in no position to give Henry what he wanted and therefore adopted stalling measures. In 1529, after two years of tortuous negotiations, a legatine court sat in London to determine what had become known as the King's Great Matter, but the case was revoked to Rome, and the Pope continued to dither and prevaricate. Goaded beyond endurance by the frustrating delays that did no credit to a church already falling into disrepute, the King, backed by support from the universities of Europe, broke with Rome and had himself proclaimed Supreme Head of the Church of England. His new Archbishop of Canterbury, Thomas Cranmer, declared Henry's marriage to Katherine invalid in 1533. By then, Henry had already married Anne Boleyn in secret, and she was pregnant with what he hoped would be a son.

Anne Boleyn had long been identified with the court faction favouring reform of the Church, and now she lent her wholehearted support to the Reformation that followed the break with Rome. Certainly, political expediency played a role in this, but there can be little doubt that her convictions were sincere. Yet she was no Protestant, as many of her enemies asserted. In an effort to counteract the earlier scandal caused by her notorious affair with the King, Anne set virtuous standards for her household and was generous in her charitable works. Yet after her pregnancy resulted in another daughter - the future Elizabeth I - she knew no peace of mind. Supporters of the exiled Katherine and Mary worked to bring Anne down, and she knew that her future security depended on bearing a son. Anxiety made her shrewish, and this affected her relationship with the King, which was never anything but volatile. Marriage had made Henry complacent, and he began taking mistresses again, causing more quarrels.

Anne's second pregnancy ended in disaster and total secrecy in 1534. By the end of 1535 she was pregnant again, but Henry's attentions had turned to her lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour. The death of Katherine of Aragon in January 1536 may have led the Queen to feel more secure, yet on the day of Katherine's funeral, Anne's son - the boy who might have been her saviour - was born dead. Her enemies moved in to destroy her and her faction, charging them with criminal intercourse and with plotting to murder the King - charges that seemed credible, given the Queen's reputation. Yet even the hostile Imperial Ambassador believed they were merely an invention to get rid of her. In May 1536, a swordsman specially imported from France beheaded Anne. Henry, wearing white mourning, was formally betrothed to Jane Seymour on the following day. They were married ten days later.

Hans Holbein's portrait reveals that Jane Seymour was no beauty; she had a very white complexion, a pursed mouth, and an over-large nose. People doubted whether, having been at court for so long - she had served Katherine of Aragon as well as Anne Boleyn - she was still a virgin. The King's courtship of her had been encouraged and manipulated by Anne's enemies, and she had played the part of a virtuous maiden, yet there is no doubt that her placid exterior hid a tougher streak. As queen, she was very much on her dignity. She was kind to the King's daughters and a meek and dutiful wife to her husband, who was no longer the Adonis he had been in youth. Rather, Henry was developing into a tyrannical colossus with firm convictions of his divinely delegated authority. When Jane dared protest against the Dissolution of the Monasteries, he brutally reminded her that his last Queen had died for meddling in affairs that did not concern her. Yet Jane gave Henry the son he wanted, and for that he remained enduringly grateful. When Prince Edward was born in October 1537, his happiness was complete. Twelve days later, however, Jane died of puerperal fever, and he plunged into very genuine grief, shutting himself away for a time. Nevertheless, political reality intruded: the Prince was but one fragile life and needed a brother. Before Jane had been buried at Windsor, where the King would later be laid to rest beside her, he had opened negotiations for a fourth marriage.

The Pope finally excommunicated Henry a year later, and the King of France and the Emperor united against him. Henry, driven to seek an alliance with the Protestant German princes, decided to marry Anne of Cleves and sent Hans Holbein to Dusseldorf to paint her portrait. The King fell in love with her picture, and on New Year's Day 1540 he hastened to Rochester to welcome Anne to England. They met only briefly, and when Henry emerged, he muttered, "I like her not!" It wasn't so much her looks that put him off but the fact that she had "evil humours about her" - she smelled. Protesting loudly, Henry went through with the marriage. On his wedding night he pawed his bride but declined to go further. The next day he pronounced her no virgin and declared he was unable to consummate the union. The amiable Anne was later banished to Richmond, and her marriage was annulled after six months. She received a handsome settlement and chose to stay on in England as the King's "dear sister." Indeed, she and Henry remained on such good terms after their separation that rumours persisted that he would take her back.

While still married to Anne, Henry had fallen for her maid-of-honour, Katherine Howard, an empty-headed girl, but alluringly pretty. The Catholic faction at court encouraged the affair, and as soon as Henry was free, he made Katherine his wife. He was now nearing 50, his waist measured 54 inches, and he suffered from ulcerated legs and constipation, yet he could not keep his hands off his bride and openly "caressed her more than he did the others". He showered her with jewels and gifts and indulged her every whim. So besotted was he that he did not notice her flirting with the young men of the court. Nor did he have any idea that Katherine had a past.

In November 1541 the King went to chapel to give thanks for his "rose without a thorn". By his seat lay a letter from Cranmer detailing information he had received about the Queen's affairs before her marriage. Henry did not believe it at first, but when further incontrovertible evidence followed, not only of fornication but also adultery, he broke down in Council and called for a sword to slay Katherine. The Queen was arrested - the legend that she broke free from her guards and ran screaming through Hampton Court Palace in an attempt to beg mercy from the King is just a picturesque fabrication. She met the same fate as Anne Boleyn, leaving her husband prematurely aged, depressed, and irascible.

Henry probably married his sixth wife, Katherine Parr, for companionship in his declining years. A mature widow of great erudition, she proved to be an admirable stepmother to the King's three children, and she set an edifying example for the court. Yet she, too, had a secret. She was a closet Protestant at a time when Protestants were being burned as heretics, and with her ladies, who were of like mind, read forbidden books. In 1546, the Catholic faction at court brought this fact to the King's attention, and he issued a warrant for the Queen's arrest. By great good fortune, she managed to convince Henry of her innocence.

Katherine remained a devoted wife until Henry's death in January 1547. Then, with almost indecent haste, she married a younger man. In 1548, she herself died in childbirth. Of all Henry's six wives, the only one then living was Anne of Cleves, who had, perhaps, been the luckiest of them all. And the son for whom Henry had changed wives so often outlived his father by just six years. In the end, what Henry had striven against came to pass: the crown descended in the female line, first to Mary, whose reign was a disaster, and then to Elizabeth, perhaps the greatest Queen that England has ever had.

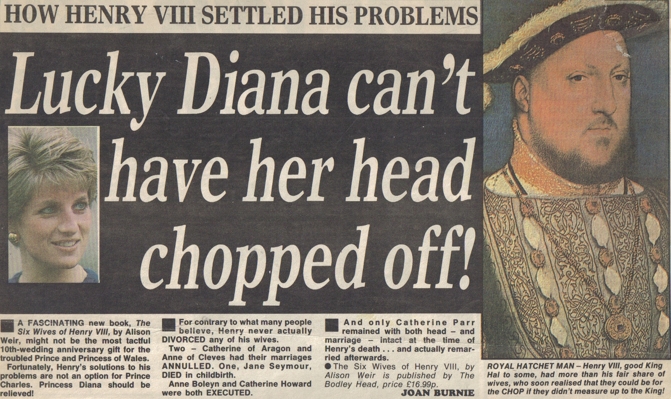

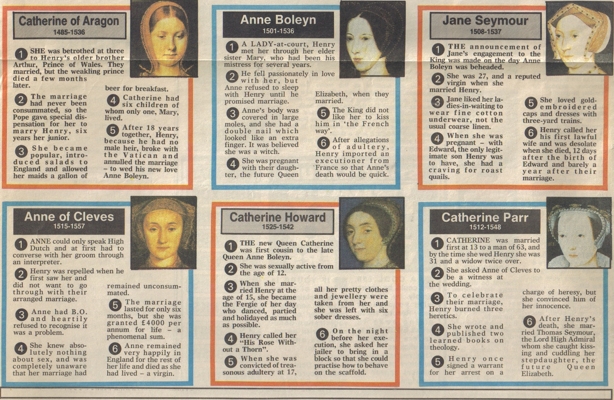

From the Daily Record, 15th July 1991

PROPOSALS FOR UNPUBLISHED BOOKS

DAUGHTERS OF SPAIN

The daughters of Ferdinand and Isabella: Katherine of Aragon and her Sisters

(Left to right, Isabella, Juana, Queen Isabella with Isabella, Juana and Maria, and Katherine)

The Catholic sovereigns, Ferdinand of Aragon and Isabella of Castile, had ten children. Only four daughters survived, and they were all brought up to be highly educated, enlightened young women, but their lives were largely overshadowed by tragedy. The eldest, Isabella (1470-1498), was a very devout girl who married firstly Alfonso of Portugal; he was killed soon afterwards in a riding accident, whereupon Isabella returned to Castile a sad and forlorn young widow who was reluctant to marry again. But four years later, for political reasons, she was obliged to bow to parental pressure and marry Alfonso`s cousin, Manuel I, King of Portugal. When Isabella`s only brother, the Infante Juan, died tragically in 1497, she became heiress to Castile and Aragon. In 1498, she bore a son, Miguel, but died an hour after his birth. Miguel died in infancy.

That left Juana (1479-1555) as heir to the Spanish sovereigns. She had perhaps the most tragic and dramatic life of the four sisters. In 1496, she married Philip the Fair, Duke of Burgundy, son of the Emperor Maximilian and reputedly the handsomest prince in Europe. Unfortunately for Juana, Philip was not a faithful husband, and did not return the passionate love she felt for him. Soon after her wedding, Juana began exhibiting a degree of mental instability, and started reacting violently towards Philip`s mistresses. Consequently, the marriage was turbulent. In 1504, on the death of Isabella, Juana became Queen of Castile, but her husband and father refused to allow her to wield power, and ruled in her name. When Philip died young in 1506, Juana was said to have became completely unhinged. There were tales that she refused to surrender his body for burial, and dragged it around the country with her for months, periodically opening the coffin and embracing the decaying corpse. Eventually, her father Ferdinand, determined to rule Castile in her name, had her shut up in the castle of Tordesillas, where she was to remain for nearly fifty years. She is known to history as Juana the Mad, and is the subject of a recent award-winning Spanish film, `Mad Love`. Yet for all its tragedy and pathos, Juana`s marriage was to be extraordinarily successful from the dynastic and political point of view. Her eldest son became the Emperor Charles V, who ruled more of Europe than any monarch since Charlemagne, and her grandson was the celebrated Philip II of Spain.

The third daughter, Maria (1482-1517), married her sister Isabella`s widower, Manuel I, King of Portugal, in 1500. Maria was the only one of the four sisters to enjoy a full and happy life. She gave her husband eight healthy children as heirs to his kingdom.

By far the most famous of the sisters was the youngest, Catalina (Katherine) (1485-1536), who married Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales, heir to the throne of England, in 1501. Arthur died six months later of a mysterious disease. Even more mysterious - and controversial - was the truth about whether the marriage had been consummated. For Katherine`s second husband was Arthur`s younger brother, who became Henry VIII, and in 1527, he applied to the Pope for an annulment on the grounds that his marriage to his brother`s widow was unlawful, since his brother had known her carnally. Katherine swore otherwise... She died, abandoned and a prisoner, in 1536.

The story of these four sisters, which is played out within the context of one of the most vivid and spectacular periods in history, is one that has never before been told in full.

ARTHUR - THE LOST TUDOR KING

Book proposal written some years before new evidence came to light about the marriage of Arthur Tudor and Katherine of Aragon.

Arthur, Prince of Wales was the eldest son and heir of Henry VII, the first Tudor King. He was born in 1486 in Winchester, which his father, anxious to emphasise his supposed descent from Cadwaladr and the ancient kings of Briton, identified with the mythical Camelot; to underline the connection, he named his son after the legendary hero King Arthur.

Henry VII had ascended the throne a year earlier after defeating the Yorkist King, Richard III, the last monarch of the Plantagenet dynasty, at the Battle of Bosworth. To strengthen his own weak title, Henry married Richard's niece, Elizabeth of York, daughter of Edward IV and elder sister of Edward V and Richard, Duke of York, the Princes in the Tower, who mysteriously disappeared during the reign of Richard III, who probably had them murdered. Elizabeth was to bear Henry three sons and four daughters, before dying in childbed in 1503. The marriage appears to have been happy.

As the future king of England, Arthur received a fine education from the best tutors that could be found. When he was two, negotiations began for his marriage to the Infanta Katherine of Aragon, daughter of the Spanish sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella. This was a brilliant match that would bring the Tudor dynasty international recognition, but the wily Ferdinand of Aragon was determined to ensure that that dynasty was securely established before permitting his daughter's betrothal. There were living at that time several scions of the House of York, all posing a threat to Henry VII's security; chief of these was Edward, Earl of Warwick, a youth of limited mental capacity, whom Henry VII had shut up in the Tower. Attempts had been made to impersonate him by two pretenders, Lambert Simnel and Perkin Warbeck. Warbeck afterwards claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes in the Tower.

It was only after Warbeck and Warwick were executed in 1499 that King Ferdinand agreed to the betrothal of Arthur and Katherine. They were married in November, 1501 in a splendid ceremony at St Paul's Cathedral in London, the last royal wedding to take place there until that of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer, 480 years later. Arthur was then fifteen, Katherine almost a year older. Like many royal couples, they hardly knew each other, their courtship having been conducted by a formal correspondence in Latin, closely supervised by tutors. Arthur's health was not good, and there was much debate as to the wisdom of allowing him to cohabit with his bride. But when Arthur was sent to live at Ludlow, where he was learning to govern his principality of Wales, Katherine went with him, much against Henry VII's better judgement. To all intents and purposes, the young couple then lived together as husband and wi fe.

Tragically, Arthur died on 2 April, 1502, to the great grief of his parents. Years later, Katherine would see his death, and the many troubles she suffered afterwards, as divine retribution for her marriage having been made in blood, the blood of the innocent Earl of Warwick. Arthur's death left his younger brother, Henry, heir to the Tudor throne, and when he succeeded as Henry VIII in 1509, one of his first acts was to marry his brother's widow, Katherine of Aragon, who had spent the seven years of her widowhood in increasing penury and misery, thanks to squabbles between Henry VII and her father over the payment of her dowry and uncertainty as to her future.

Such are the bare bones of Arthue's life and his place in English history. He may seem not to have lived long enough to merit a biography, but it was an age of short-lived royal males and several have recently been the subject of biographies, notably of Edward V (the elder of the Princes in the Tower, who died at thirteen, whose life has been written by Michael Hicks; that of Henry Fitzroy, the bastard son of Henry VIII, who lived to just seventeen, is recounted in Bastard Prince by Beverley Murphy; and about Edward VI, who died aged fifteeen, there are numerous works, the most recent being by Diarmid MacCulloch, Chris Skidmore and Jennifer Loach. Much is known about Arthur's life, but none of it has ever been collated into a biography, with an assessment of his character and his potential as king and patron. It would be facinating to speculate on what would have happened had Arthur become king; would he have been another such as his brother Henry? Would he have fathered healthy sons, given the poor track record of the Tudors and the Spanish House of Trastamara? Certainly the course of English history would have been very different.

Just as fascinating are the mysteries that surround Arthur's life. He was almost certainly conceived before his parents' marriage, suggesting that Henry VII wanted to ensure that Elizabeth of York was capable of bearing children before he committed himself to marrying her. It is often claimed that Arthur was a sickly or delicate child, but what evidence is there for this? What did he die of: was it tuberculosis, which probably carried off his father and his nephew, Edward VI? Or perhaps he died during an outbreak of plague in the Ludlow area; it may be significant that his wife, Katherine, fell ill at the same time, but later recovered. A third, more recent theory is that he succumbed to testicular cancer.

The greatest mystery of Arthur's life, and one that was to have far-reaching repercussions for the Tudor dynasty, the royal succession and the history of England was whether or not his marriage to Katherine was consummated. In 1529, this matter was furiously debated during the court proceedings that arose from Henry VIII"s petition for an annulment of his marriage to Katherine of Aragon. The King claimed that, because she had been his brother's wife, their marriage was invalid and God was punishing them by withholding a son and heir. Many witnesses came forward to testify that they had heard Arthur boasting of his prowess on the morning after his wedding, yet Katherine herself was always to insist that she came to Henry VIII "a true maid, without touch of man". Since then, controversy has raged as to whether she was lying, but the arguments have focussed largely on the evidence put forward in 1529, rather than on evidence contemporary to the marriage of Katherine and Arthur. Were Arthur's life to be thoroughly researched, some helpful contribution might be made to this debate.

A biography of Prince Arthur would also fill a gap in Tudor studies. This youth was going to be king, he was enormously important, and by the end of his short life, he was apparently exercising a degree of power. He made one of the most brilliant marriages of the age. He was a Renaissance prince whose life was lived against a backdrop of court splendour and deadly intrigue. It is incredible that no one has so far thought to write a biography for him. Arthur is an interesting figure in himself, and he was surrounded by some of the greatest personalities of the age: his father, Henry VII, cunning and calculating, reputed a miser yet presiding over a brilliant court; his mother, Elizabeth of York, much loved and beautiful; his father's mother, Margaret Beaufort, a matriarch whose influence over the court and her grandchildren was to endure for decades; his wife, Katherine, an austerely religious and intellectual girl, well-bred and pretty; his brother. Henry, Duke of York, vital, talented and worldly, yet perhaps intended for the Church; his sisters Margaret, betrothed at twelve to James IV, King of Scots, and Mary, who was only seven when Arthur died; and those other brothers and sisters, Edmund, Edward, Elizabeth and Katherine, who died young. These were the first Tudors, and their legacy would be handed on to generations of sovereigns.

With John Guthrie, the owner of Hever Castle, in 2002, when I unveiled a portrait of Jane Seymour at Hever Castle.

The following article was written for this occasion.

Jane Seymour was the third wife of Henry VIII. The daughter of a Wiltshire knight, she was born probably in 1508, and became a maid-of-honour to the King's first wife. Ratherine of Aragon. When Katherine fell from favour, Jane transferred to the household of Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn, whom he married in 1533.

By late 1535 Henry had tired of Anne and was pursuing Jane. At 27, Jane was rather old to be unmarried, but it appears that her father could not afford to give her a rich dowry. Furthermore, Jane was no great beauty, but her charm for Henry lay in her being the complete antithesis of Anne Boleyn. She was, on the surface, quiet, demure, subservient and discreet, characteristics the King appreciated in a woman. Her behaviour over the coming months, however, suggests that she was also tough, calculating and ruthlessly ambitious. The Spanish ambassador was sceptical about Jane's much-vaunted chastity, and wondered how it could be possible that, being an Englishwoman, and having been long at court, she could still be a virgin.

In January 1536 Anne Boleyn bore the King a stillborn son, which was a shattering disappointment, as the King desperately needed a male heir to succeed him, his two marriages having produced only daughters. Henry could not have foreseen that his daughter by Anne, the future Elizabeth I, would become one of the greatest of English monarchs. Despite the crushing of his hopes, Henry showed some sympathy to Anne in the weeks after her miscarriage, but other forces were at work against her. Jane Seymour's ambitious brothers were doing their utmost to promote her liaison with the King, while exhorting her not to allow Henry to seduce her, since Henry was notorious for tiring quickly of his mistresses. Then, at the end of April, Anne's enemy, Thomas Cromwell, Henry's Secretary of State, laid before his master evidence that Anne had committed adultery with five men, one her own brother, and had plotted the King's death. Anne was sent to the Tower of London, and during the seventeem days of her imprisonment, Henry visited Jane Seymour in private, first at Beddington Park, and then in a house at Chelsea. It was probably at this time that he decided to marry her. On the day after Anne's execution, Henry and Jane were formally betrothed at Hampton Court. Ten days later, on 30 May, they were married at Whitehall Palace.

As Queen, Jane proved herself to be entirely subservient to the King's will, but to nearly everyone else she was proud and haughty, and strict over protocol and the courtesies due to her. To her credit, she did encourage a reconciliation between the King and his elder daughter, Mary, and she was kind to the motherless Elizabeth, who was not quite three when Anne Boleyn was beheaded.

Jane was never crowned. Her coronation was postponed because of plague in London and a rebellion in the north. When she tried, on her knees, to intercede for the rebels, Henry told her to get up and attend to other things, and brutally reminded her that his last Queen had died as a result of meddling too much in state affairs. Jane took this warning to heart, and never again interfered in politics, thus marital harmony was restored.

Jane's great achievement was to bear the King a son. On 12 October, 1537, the future Edward VI was born at Hampton Court after a gruelling labour lasting three days and three nights. There is no truth in the stories that the infant was born by Caesarian section or that the King, asked to choose between mother and baby, opted for the child, as other wives could easily be found; these tales were fabrications by later writers hostile to the King. Henry wept for joy as he held his son for the first time, and the country erupted in celebration. But a few days later Jane contracted puerperal fever, and on 24 October, to Henry's great grief, she died. Of all his wives, she was the one he chose to lie beside in death at Windsor, the only one to have given him a living son.

This portrait of Jane is an excellent copy of the famous portrait exceuted in 1536 by the King's Painter, the celebrated Hans Holbein, which is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Holbein himself designed the pendant on Jane's bodice and the lace at her wrists. A preliminary drawing for this portrait is in the Royal Collection at Windsor, and a copy by Holbein's studio is in the Mauritshuis at The Hague. There are several other copies in country houses around the country (of which a selection are shown above next to the Hever version on the left), but this one is undoubtedly the best.

Promoting The Six Wives of Henry VIII at a literary lunch for the English Speaking Union at Deal, 1991.

Report from the Lincolnshire Echo about my visit to Gainsborough Old Hall in 2009 to speak about The Six Wives of Henry VIII.

MISCELLANY

The series of TV plays, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, starring Keith Michell, was one of my original inspirations for this book. The series was made with such integrity and a desire to get things right and convey - on a small budget - a proper sense of the period. Yes, dramatic licence was at play, but this series is far more accurate than The Tudors, and Michell`s portrayal of Henry is second to none.

I have been interested in the subject of Henry VIII`s wives since 1965, hence my huge research project in the early 1970s. When my book was finally commissioned in 1990, I rewrote it from my original text, incorporating new research, but even then - at 900 double-spaced pages - it was too long, so I was asked to cut the text to a commercial length. That took me two months - and I did it on a typewriter! I still refer to my original text for research purposes.

People often raise queries about Henry VIII's fertility and possible impotence, or why so many of his children died in infancy or in the womb. Henry was one of eight children. Only four lived beyond infancy: Arthur, Margaret, Henry and Mary. The others were Elizabeth (died aged 3), Edmund (died aged 15 months) and Katherine, who both died soon after birth. This was not unusual in an age of high infant mortality, which affected all classes in this period, and indeed up to the eighteenth century. By Katherine of Aragon, Henry had six children: three sons who died soon after birth, Mary, who lived to maturity, a daughter who was born dead, and one who died soon after birth. Katherine of Aragon came from a family of ten: five of her siblings had died in infancy. Thus there was a history of infant mortality on both sides, which may or may not be significant. Henry's second wife, Anne Boleyn, became pregnant four times. Her first child was a daughter, Elizabeth I. Her second died at or near full term, and was almost certainly a son. Her third and fourth pregnancies ended in miscarriages, the latter of a son. This suggests that Anne was rhesus negative. Anne herself was born of parents who had a child 'every year', although only three lived to adulthood. Henry had a son by Jane Seymour, and one acknowledged bastard son by Elizabeth Blount. My extensive research for my biography of Mary Boleyn strongly suggests that the King also had two bastard daughters, both of whom married and bore children. By the time Henry married his three last wives, he was ageing, ailing and grossly obese; there is an ongoing debate about his possible impotence. On this evidence, I feel that it is not possible to say with any certainty that Henry's 'lack of issue' was due to any condition of his.

In my original draft of The Six Wives of Henry VIII, I cited a contemporary quote to the effect that Cranmer issued a dispensation because Henry VIII and Jane Seymour were `in the third and third degrees of affinity`. I have been researching the pedigrees of the English aristocracy from 1066 to 1603 since the late Sixties, and have charts for every family, but the work is still by no means complete. I had done a lot of genealogical research on the families of Henry`s wives that led me to believe - incorrectly - that Elizabeth Neville, the second wife of Sir Henry Wentworth, was Jane Seymour`s grandmother. Long after my book was published, I discovered that Jane's mother, Margaret Wentworth, was the daughter of Sir Henry`s first wife, Anne Say. The whole question of a dispensation may be spurious. A chart showing the descents of Henry and Jane to the third degree shows that there is no affinity at all. The families are Tudor, Valois, Beauchamp, Plantagenet, Neville, Wydeville, Luxembourg, Seymour, Coker, Darell, Stourton, Wentworth, Clifford, Say and Cheyne. The links are further back. At that time, there was an impediment to marriage up to the fourth degree, so there would have been no need for a dispensation for a blood tie dating from Edward III.

We don`t know for certain when or how Henry VIII`s love letters to Anne Boleyn arrived at the Vatican Library. There are various theories: that they were stolen by an agent of either the Papal Legate, Cardinal Campeggio or the Imperial ambassador, Eustache Chapuys, or sent by Cardinal Wolsey after his fall from favour; or they might have been found at Hever by the Catholic Waldegrave family (who owned the castle after Anne of Cleves died), and been sent to Rome by them. They are private letters, and their existence was not known of in England until the late 17th century, when Bishop Burnet examined them. The Vatican allowed them to be copied and printed soon afterwards.

Surprisingly, even Henry VIII consulted soothsayers for predictions of the sex of his children. It was a superstitious age, but readers should approach with caution the claim that Henry declared he`d been seduced into marriage by witchcraft - it came to Chapuys fourth-hand, and there is no mention of witchcraft in the indictments against Anne. The whole witchcraft aspect has been much overstated.

Emilia Fox, the actress, was asked by The Mail on Sunday what was in her holiday hand luggage. Her answer: 'A copy of The Six Wives of Henry VIII by Alison Weir." (2003)

Reader Vivian Grant Farrell, President of the International Fund for Horses, wrote to say that she had visited Peterborough Cathedral where Katherine of Aragon is buried. 'I photographed her tomb, and when I got the film developed you could see the complete outline of a lady. I was surprised as my flash had failed. I remember my mother acting as if she could not get out of there fast enough, and commenting, "That will never come out." When I showed her the picture, she and I just looked at each other. Neither of us uttered a word. That was before the digital age, and I have since lost both the photograph and negative.' But Vivian is searching for them, and hopefully will get back to me.

Reader Adrian Mills tells me that, in the introduction to the audio book, Katherine Parr is referred to as 'Katherine Pratt' - a 'faux-Parr', he says!