Books

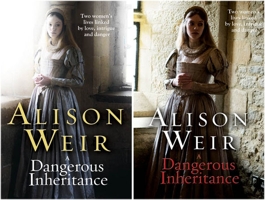

A Dangerous Inheritance (2012)

"A Dangerous Inheritance approaches the story of Lady Katherine Grey in a new and innovative way. [It] is sharp and pungent at times in its consideration of early modern politics and identity." (History Today)

"I have just finished it and I loved it! I was totally spellbound and wrapped up for two days. I can't tell you the amount of times I held my breath, and cried. I have a little boy and am very glad I am not born into royalty! Absolutely brilliant, am so looking forward to working the book!" (Fenella Davidson, Publicity Manager, Random House Australia)

"[The story in] Alison Weir's stunning new novel [is] told with suitably dramatic embellishment... Weir's spine-tingling tale leaves us in no doubt that Katherine's transgression is not one of sex or etiquette but the unpardonable one of being born to the blood royal... Weir spins a story with as many twists and turns as a spiral Tower staircase, down which we eagerly follow her. It all makes for a richly layered cake of love, sex, danger, death and mystery, put together by Weir's impeccable scholarship. Not for nothing is she among our top five bestselling historians, as she knows how to tell a hypnotic yet factual tale. It seems we cannot get enough of the Tudors, and with Weir as our guide through the labyrinth, we are in an expert's confident hands." (Nigel Jones (author of Tower), Sunday Express)

"Historian Alison Weir, who has found a fresh and firm footing as a novelist, plucks two little-known characters from the footnotes of English history and intertwines their fates in an enthralling tale of murder, mystery and love. A Dangerous Inheritance, Weir’s third and undoubtedly best historical novel, is proof indeed that she has mastered the popular and beguiling ‘faction’ formula in which fictional events slip seamlessly into an authentic historical framework.

"Alison Weir has produced a terrific book, full of vivid storytelling, fascinating history and all those ingredients – romance, danger, mystery and suspense – which bring the past to life in such stunning detail, colour and atmosphere.

"An entertaining and absorbing read from the new queen of historical fiction." (Lancashire Evening Post)

"Alison is an impeccable researcher, a brilliant writer and a gifted storyteller... Full of romance and history - you'll be enthralled." (Your Family Tree magazine)

"Renowned historical biographer Weir [writes] a novel set against the tumultuous political backdrop of two eras, Plantagenet and Elizabethan. . . Alternating viewpoints, an intriguing unsolved mystery, ghosts, romance and history entangle to present a plausible, well-written blend of fact and fiction." (Romantic Times)

"Weir stands with equally secure footing in history and fiction. Her latest book finds her on familiar historical terrain, this time in a fictional journey creatively connecting two time periods... A novel compelling in its complexity." (Booklist)

"What a wonderful story, and what fabulous characters you have created. It was inspired choosing the two Katherines like that, as their stories were interlinked in a way that is not immediately obvious. You brought them to life beautifully, and I found could relate to each one equally. I also liked the way the story evoked the feel of the period; everything became real, lifted out of dusty archives and brought to vivid life. One scene I particularly liked was the one where Katherine became aware of the presence of Kate and immediately formed an affinity with her." (Josephine Wilkinson, author of Richard III: The Young King To Be)

"Weir cleverly tells the story of Katherine Grey, while at the same time telling the story of Kate Plantagenet... Weir takes a unique approach... She also offers a balanced portrayal of Richard III." (Portland Book Review)

Ladies Home Journal book reccomendation.

"The stories of two Englishwomen, born a century apart, are a juicy mix of romance, drama and Tudor history - and pure bliss for today's royal watchers." (Ladies Home Journal)

“Beautifully written . . . the story of these two women [is] highly compelling [with] plenty to keep readers enthralled.” (Historical Novel Review)

“A page turner . . . too juicy to put down. Alison Weir’s strong suit as a fiction writer is making her novels living history.” (The Courier-Journal)

“With its evident in-depth research and creative twists, this tale of two women trying to make sense of the power of the English crown is nothing short of riveting.” (Library Journal - starred review)

“No one alive knows as much about the Tudors as Weir. Any reader of Hilary Mantel’s excellent Tudor evocations will want to explore this book as well.” (Kirkus Reviews)

“A Dangerous Inheritance is a must-read for any lover of English historical fiction.” (Luxury Reading)

“A tale of two voices, two eras, and two royal upheavals . . , by far [Weir’s] most ambitious and satisfying novel to date.” (Open Letters Monthly)

"Stunning Tudor fiction." (Bookbub)

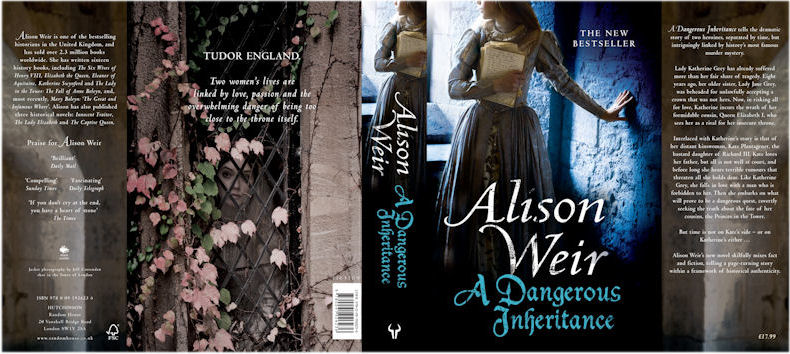

My fourth historical novel was published on 21st June in the U.K. and on 2nd October in the U.S.A.. The jacket image was shot in the Tower of London, where the heroine, Lady Katherine Grey, was imprisoned. What is the significance of the pendant she is clutching? Is it possible that the secret papers she is holding contain the truth about one of the greatest mysteries in history? And why is Katherine so scared...?

A Dangerous Inheritance is the stand-alone sequel to Innocent Traitor. It tells the story of two beautiful, tragic heroines, Lady Katherine Grey (above) and Katherine Plantagenet.

Above is a gallery of the major historical characters in the novel: Lady Katherine Grey; Frances Brandon, Duchess of Suffolk (?); Lady Jane Grey, as depicted by Paul Delaroche; Queen Mary I; Queen Elizabeth I; King Richard III; the still on the right shows Claire Bloom as the Lady Anne in the film Richard III, there being no portrait of Anne Neville.

A DANGEROUS INHERITANCE: THE HISTORY BEHIND THE FICTION

by ALISON WEIR

The Tower of London, 1562. At a time when Queen Elizabeth I sat insecurely on the English throne, a young woman of twenty-two was arrested and imprisoned. She was the Queen`s cousin, and she had dared to marry her lover secretly and produce a child who might live to challenge Elizabeth`s title. The question on everyone’s lips was: would the Queen demand the dread penalty for treason?

This hapless young woman was Lady Katherine Grey, and in her short life she had already suffered more than her fair share of tragedy. Eight years before, her older sister, Lady Jane Grey, had been beheaded for treasonously, if unwillingly, accepting the English crown and reigning unlawfully for nine days. Katherine was a victim of Jane`s fall, for her brief but happy first marriage, to Henry, Lord Herbert, was speedily dissolved; his father did not want his line tainted by association with a traitor. He had not even allowed the young couple to consummate their union, envisaging, correctly, that things might go very wrong for those who had put Lady Jane on the throne.

Katherine felt the parting from her husband keenly, and for many years she hoped that they might be reunited, but it was not to be. Then she met Edward Seymour, nephew of Queen Jane Seymour, and fell in love headily - and disastrously. For many regarded Katherine as the rightful heir to Elizabeth`s throne, and the Queen was jealous: she would not tolerate a rival, or allow Katherine to marry. But Katherine defied her, and when her pregnancy could be concealed no longer, she found herself a prisoner in the Tower.

A Dangerous Inheritance is a novel based on Katherine’s life, and researched from contemporary sources. In telling her story, I have adhered to the known facts, although I have taken a little dramatic licence, all explained in the Author’s Note at the end of the book. There are quotes from contemporary documents, and the letters are genuine. Archaic language has been modified to blend in with a modern text, although I have made use of many contemporary idioms.

The course of Katherine’s courtship by Edward Seymour, and his sister’s role in it, was much as it is portrayed in the novel, and the account of their wedding day – and ‘night’ – is based closely on their own depositions. Katherine’s love for Edward was the overriding passion of her life, and she remained staunchly faithful through every trial, until her death.

Katherine is not the only heroine in this book. She is linked by marriage and (in the novel) supernatural ties, to a girl who lived eighty years earlier, and whose true story is lost in the mists of time.

Katherine Plantagenet, the bastard daughter of King Richard III, is known to history only through four grants relating to her marriage to William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon in 1484, and the financial settlements relating to it. From this and from circumstantial evidence and credible inference, Alison Weir has woven a fictional tale around her. Thus the story flashes back nearly eighty years, to 1483, when thirteen-year-old Kate Plantagenet is brought to London for Richard’s coronation. Kate loves her father, and she has been well-treated by his Queen, Anne Neville, in whose household she has been reared with her two half-brothers, Edward of Middleham, Prince of Wales, and John, the Bastard of Gloucester – all historical figures.

But all is not well at court, and soon after her arrival, Kate senses sinister undercurrents. Her father has gained his throne by disinheriting and deposing his nephew, the young King Edward V, and has imprisoned the former King and his brother in the Tower of London. Before long, Kate hears terrible rumours that King Richard has had the two Princes in the Tower murdered. This throws her into turmoil. Like many at the time, and since, she wants to know the truth about the Princes’ disappearance.

Writing about Richard III from the viewpoint of a daughter who wanted to believe the best of him proved a challenging experience, because in 1992 I published a book entitled The Princes in the Tower, in which I investigated the ancient but still highly controversial mystery of their disappearance, and concluded that strong evidence pointed to Richard III having ordered their murder. Do I revise my conclusions in this novel? You’ll have to read it to find out.

The fictional Kate resolves to discover the truth, hoping that she will be able to prove that her father has not shed the blood of innocents. And so she embarks on what will prove to be a dangerous quest. But time is not on her side.

Meanwhile, in the Tower, Katherine Grey becomes increasingly perturbed by eerie dreams and phantom voices, and wonders if these manifestations are somehow related to the disappearance of the Princes in this very fortress eighty years before. Katherine’s interest in the mystery is emotional, bound up with her fears for her baby son, who is too near in blood to the throne for comfort – just like the Princes. And so, with the help of her kindly gaoler, Sir Edmund Warner, she too sets out to find the truth. The two girls’ quests are pure fiction, but the evidence they uncover is based on fact, although I had to take into account which sources would have been available to them in 1483-5 and 1562.

Historically, Sir Edward Warner was a sympathetic custodian. He allowed Seymour to visit Katherine in the Tower, with the result that she fell pregnant again. Time was not on her side either.

There is a third prominent female character in the novel: Elizabeth I. If Elizabeth was Katherine’s bête noir, Katherine was hers – and with good cause, for Elizabeth had compelling reasons for fearing the woman whom many regarded as her legal successor. One can feel sympathy for both women, but my Elizabeth is a more menacing character, reminiscent of her grandfather, Henry VII. The Interludes in the book are there to show Elizabeth’s point of view; without them, she comes across as a cruel persecutor.

The fictional Kate’s pendant is modelled on the famous Middleham Jewel. The bundle of papers tied up in a ribbon is, sadly, an invention.

A constant theme in the novel is the danger of being too close in blood to the throne. Under the Act of Succession, Lady Katherine Grey was Elizabeth I’s heir, but Elizabeth was paranoid about naming her successor, for fear of forming a faction that would plot against her. Thus Katherine was damned in Elizabeth’s eyes from the start. Elizabeth would not allow her to marry because she feared that her husband would press her claim to the throne, and that any son she bore would be seen as preferential to a female ruler. Katherine’s folly in marrying secretly for love, and producing two sons, was anathema to the Virgin Queen, who denied herself the comforts of marriage for political and, probably, psychological reasons.

It is possible that Katherine’s head was so turned when she saw her sister made queen that for ever after her ambitions were focused on wearing a crown. This is the only theory that makes sense of her behaviour. In my view, she was not a would-be traitor but a self-obsessed girl who let her heart rule her head and did not think things through logically. Her instincts were emotional rather than rational. Because of that, she ended up out of her depth, in deep trouble.

It is unlikely that Katherine wanted to supplant Elizabeth; rather, she wished to be acknowledged as her successor. William Cecil’s enquiries persuaded him that Katherine’s union with Seymour was no more than a love match – he called it ‘that troublesome, fond matter’ – and not part of a plot against Elizabeth, yet whatever his private feelings, he followed the Queen’s lead in punishing the couple.

The fictional Kate Plantagenet finds her kinship with Richard III a threat to Henry VII, the man who overthrew him, and to her husband, who no longer wants to be married to the daughter of a king who has been branded a usurper and murderer. Continuing the theme, by their very existence, the historical Princes in the Tower remained a threat to Richard III after he declared them bastards and had Edward V deposed. Risings in their favour convinced him that he would never be secure on his throne while they lived. The historical Elizabeth I had grown up in the shadow of the Tower: her mother, Anne Boleyn, had been executed there for treason, as had others who were close to her; and she herself was imprisoned there in youth, expecting to be executed daily. Elizabeth too had known the stain of bastardy, and how easy it was to become the focus of others’ plots, which had been the fate of the executed Lady Jane Grey. All these women – Elizabeth, Jane and Katherine – endured danger and tragedy because of the royal blood that ran in their veins. For them all, it was a dangerous inheritance.

Above are the original UK jacket concepts for the book. They are not intended to be accurate in terms of costume and location, but to give an idea of the design and colour scheme.

Above, and at the bottom of the page, are preliminary UK hardback and paperback (bottom two rows) jacket designs. The actual colour of the gown, which I chose myself at Angel's, the theatrical costumiers, is ivory.

I LAUNCHED A DANGEROUS INHERITANCE AT THE TOWER OF LONDON

Lorna Fergusson, author of The Chase, one of my favourite novels, was a guest at the launch, and has posted a blog about it at http://literascribe.blogspot.com. For more info about Lorna, go to www.fictionfire.co.uk. The Chase, a haunting mystery set in the Dordogne, a part of France I love and know well, was reissued as an e-book in the autumn.

The launch party for the book was held at Cheyneygates, the fourteenth-centry former abbot's house in Westminster Abbey, and the oldest house in London.

I gave this speech about the house:

"You are standing in a very important and historic house, the oldest house in London, which dates from the fourteenth century. Cheyneygates is the former house of the pre-Reformation abbots of Westminster, and it has been the setting for momentous historical events. Enter these rooms, and you are treading in the footsteps of kings, queens and great men.

In 1470, during the Wars of the Roses, when King Edward IV was exiled, his queen, Elizabeth Wydeville, fled into sanctuary in the Abbey with her three young daughters, the eldest of whom was Elizabeth of York, the future queen of Henry VII and mother of Henry VIII. The kindly Abbot Mylling could not allow the Queen to rub shoulders with felons and thieves in the common sanctuary building that occupied the site of Middlesex Guildhall, so he kindly accommodated her and her children in this, his palatial house, where she was very royally housed. In November that year, a king was born here, the prince who would become Edward V, the elder of the ill-fated Princes in the Tower.

Edward IV returned in triumph the following year, but when he died in 1483, his widow, Elizabeth Wydeville, sought sanctuary here in Cheyneygates yet again, fearing the ambitions of Richard of Gloucester, the future Richard III. This time, she came accompanied by her five daughters and younger son, Richard of York, plus a huge amount of baggage – so much that a wall had to be taken down to get it all in. The Abbot’s response in not recorded. Her elder son, the young King Edward V, was lodged in the Tower, and much pressure was put on the Queen to allow the younger boy, York, to join him there. It was here, on 16th June 1483, that she reluctantly let him go. The Princes in the Tower disappeared just a few weeks later.

In 1486 Cheyneygates was leased to Elizabeth Woodville, although she only lived there for a few months. Her son-in-law, Henry VII, often dined here with Abbot Islip, and was served the Abbey’s famed marrowbone pudding. In 1509, Henry’s mother, the formidable Margaret Beaufort, died in Cheyneygates; and it was in these rooms, in 1534, that Sir Thomas More was kept in custody before his removal to prison in the Tower.

After the Reformation the Abbot’s House became the Deanery and in the 19th century Cheyneygates was used as the Dean’s study. In 1941, however, the Deanery and Cheyneygates were badly damaged. The rooms were subsequently reconstructed. These are the only ones to which the public may enjoy privileged access. The famous Jerusalem Chamber, where Henry IV died in 1413, is now part of the Deanery, which is private.

Westminster has a special resonance for me. I was born at St Thomas’s, just across the Thames, and spent my childhood in a fine mansion flat opposite County Hall. Big Ben chimed its way through my formative years. So I always feel, when I come to Westminster, that I am coming home."

A DANGEROUS INHERITANCE

by ALISON WEIR

Article written for the Daily Telegraph, 2012

Tomb effigy of Lady Katherine Grey in Salisbury Cathedral

In this Jubilee year, the royals are at their most popular, and even a year on from William and Kate’s wedding, all eyes are still on the heirs to the throne, who visibly bask in the Queen’s approval. But it wasn’t always this way – and this is the main theme of my new novel, A Dangerous Inheritance, which tells the story of two young women who lived in an age in which royal heirs who were perceived as a threat to the monarch were swiftly dealt with. The two female heroines, Lady Katherine Grey and Katherine Plantagenet, are linked in more ways than one, but mainly because they are both in danger for being too close in blood to the throne.

Katherine Grey was cousin to Queen Elizabeth I. In 1562, at a time when Elizabeth’s throne was by no means secure, Katherine dared to marry in secret and produced a child who might live to challenge the Queen’s title. Inevitably, she ended up in the Tower, in peril of death.

Katherine had already suffered tragedy. Eight years before, her older sister, Lady Jane Grey, had been beheaded for treasonously, if unwillingly, accepting the English crown and reigning unlawfully for nine days. Katherine was a victim of Jane`s fall, for her brief but happy first marriage, to Henry, Lord Herbert, was speedily dissolved; his father did not want his line tainted by association with a traitor. He had not even allowed the young couple to consummate their union, envisaging, correctly, that things might go very wrong for those who had put Lady Jane on the throne.

Katherine felt the parting from her husband keenly, and for many years she hoped that they might be reunited, but it was not to be. Then she met Edward Seymour, nephew of Queen Jane Seymour (Henry VIII’s third wife), and fell in love headily - and disastrously. For Katherine was the heir to Elizabeth`s throne, and the Queen was jealous: she would not tolerate a rival, and had forbidden Katherine to wed. Katherine’s folly in marrying secretly for love, and producing a son, was anathema to the Virgin Queen, who denied herself the comforts of marriage for political and, probably, psychological reasons. But Katherine’s love for Edward was the overriding passion of her life, and she was to remain staunchly faithful through every trial, until her death.

Katherine Grey’s tale is interwoven with that of a spirited, beautiful girl who lived eighty years earlier. The two are linked by marriage and (in the novel) supernatural experiences.

Katherine Plantagenet, the bastard daughter of King Richard III, is known to history only through four grants relating to her marriage to William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon. From this and from circumstantial evidence and credible inference, I have recreated her story. Thus the narrative flashes back eighty years, to 1483, when thirteen-year-old Kate Plantagenet is brought to London for Richard’s coronation. Kate loves her father, but soon after her arrival at court, she senses sinister undercurrents. King Richard has gained his throne by disinheriting and deposing his nephew, the young King Edward V, and has imprisoned the former King and his brother, the Duke of York, in the Tower of London. Before long, Kate hears appalling rumours that her father has had the two Princes in the Tower murdered. This throws her into turmoil: Like many people at the time, and since, she wants to know the truth about the Princes’ disappearance.

Writing about Richard III from the viewpoint of a daughter who wanted to believe the best of him proved a challenging experience, because in 1992 I published a book entitled The Princes in the Tower, in which I investigated the ancient but still highly controversial mystery of their disappearance, and concluded that the evidence strongly suggests that Richard III did order their murder. In this novel, my aim was to present him in a more positive light, through the eyes of the daughter who loved him.

Hoping that she will be able to prove that her father has not shed the blood of innocents, Kate embarks on what will prove to be a dangerous quest. But time is not on her side.

Meanwhile, in the Tower, Katherine Grey becomes increasingly perturbed by eerie dreams and phantom voices, and wonders if these manifestations are somehow related to the disappearance of the Princes in this very fortress, eighty years before. Katherine’s interest in the mystery is emotional, bound up with her fears for her baby son, who is too near in blood to the throne for comfort – just like the Princes. And so, with the help of her kindly gaoler, Sir Edmund Warner, she too sets out to find the truth. The evidence the two girls uncover is based on fact, although I had to take into account which sources would have been available to them in 1483-5 and 1562.

Katherine Grey’s sojourn in the Tower was relatively comfortable. Warner was a sympathetic custodian and allowed Edward Seymour to visit Katherine, with the result that she fell pregnant again, with grievous consequences. Time was not on her side either.

A constant theme in the novel is the danger of being too close in blood to the throne. Katherine Grey was Elizabeth’s heir, but it’s unlikely that she wanted to supplant the Queen; rather, she wished to be acknowledged as her successor, which Elizabeth would not do. It is possible that Katherine’s head was so turned when she saw her sister Jane made queen that for ever after her ambitions were focused on wearing a crown. In my view, she was a naïve girl who let her heart rule her head and did not think things through logically. Her instincts were emotional rather than rational. Because of that, she ended up out of her depth, in deep trouble.

The fictional Kate Plantagenet is not Richard III’s heir, but after he is defeated at the battle of Bosworth by Henry Tudor, her kinship to the fallen monarch is a threat to the usurper, now Henry VII, and to her husband, who no longer wants to be married to the daughter of a king who has been branded a tyrant. Continuing the theme, by their very existence, the historical Princes in the Tower remained a threat to Richard III after he declared them bastards and had Edward V deposed. Plots in their favour convinced him that he would never be secure on his throne while they lived.

Elizabeth I had grown up in the shadow of the Tower: her mother, Anne Boleyn, had been executed there for treason, as had others who were close to Elizabeth; and she herself was imprisoned there at twenty, daily expecting to be executed for her suspected involvement in a rebellion to put her on the throne in place of her sister, Mary I. Elizabeth too had known the stain of bastardy, and how easy it was to become the focus of others’ plots, which had been the fate of the executed Lady Jane Grey.

Fortunately, we live in more enlightened times: the last royal to suffer execution was Charles I in 1649, and since Tudor times the succession to the crown has never been so disputed. Unlike Elizabeth I, Lady Jane Grey, the Princes and my two heroines, young royals today do not have to endure danger and tragedy because of the blue blood that runs in their veins. For them, mercifully, it is no longer a dangerous inheritance.

TALKING SHOP WITH NANCY BILYEAU!

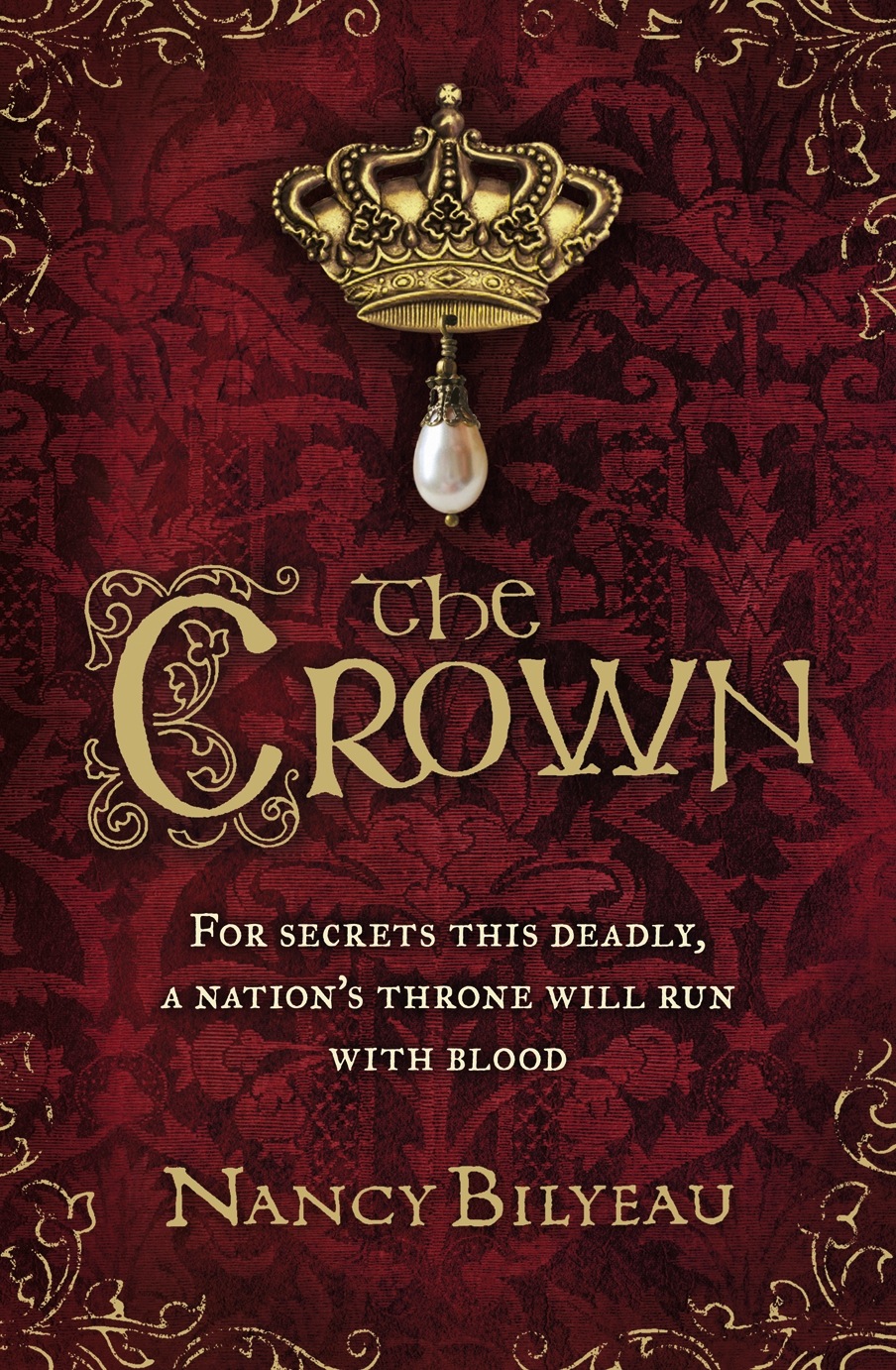

Nancy Bilyeau is the author of The Crown, a stunning debut historical novel set in Dartford Priory in the sixteenth century, and its sequel, The Chalice.

NB: I believe I’ve read every single one of your books and just finished your latest, A Dangerous Inheritance. After I read The Lady in the Tower, I was shaken, because it drove home to me as never before the pitiable tragedy of Anne Boleyn, and how abandoned she was by all after her husband turned on her. What’s interesting is that after I finished A Dangerous Inheritance, I felt disturbed, too, by how lost in their dangerous times these two women were, Katherine Grey and Kate Plantagenet. Was that one of your goals in writing the book, to illuminate how less well known women of that age could come to tragedy?

AW: Yes, it was. I am always interested in retrieving women’s histories, and I wanted to show how the constraints of noble birth, royal blood and gender could impact on young girls.

NB: Did you become intrigued by Katherine Grey while researching Lady Jane Grey for your novel and earlier books and decide to tell her story as well? And how different she was from her sister!

AW: I became intrigued years ago when I read Two Tudor Portraits by Hester W. Chapman. I wrote Katherine’s story in Elizabeth the Queen, but not in any great depth, but I knew enough of it to know that it was a very dramatic tale – and a tragic one. She was very different from Lady Jane Grey: she was beautiful where Jane was plain, placid where Jane was feisty; she was no bluestocking or formidably learned, as Jane was, and in some ways she comes across as lacking in common sense and forethought, but one cannot but feel sympathy for her.

NB: What do you think of the current theory that Frances Brandon was not as abusive to her daughter Jane Grey as historically assumed? She is a complex figure in your book.

AW: I don’t buy it! We have Jane’s own testimony and other evidence. But maybe Henry Grey was even more unpleasant!

NB: Elizabeth I is known to have disliked Katherine Grey and refused to name her heir even before the scandalous marriage and pregnancy. Do you think the dislike was at all justified and would Katherine Grey have made a good queen of England in the 16th century?

AW: Katherine’s own behaviour – her failure to convert back to the Protestant faith and her flirtations with Spain – was not conducive to Elizabeth thinking kindly of her, but Elizabeth was pretty paranoid about anyone with a claim to the succession, so Katherine was damned from the start. She was pretty and she was younger than the Queen – red rags to a bull! – and she acted very rashly in marrying Edward Seymour. It undermined Elizabeth’s policy, threatened her throne, and must have been galling to a queen who rejected marriage for political – and probably psychological – reasons. Katherine did not have what it took to be a queen, neither the brains nor the resolve. She lived in a fantasy world. I can understand why Elizabeth was harsh with her – and in many ways I think it was justified.

NB: How much is known about Kate Plantagenet? Was it more challenging or more interesting to develop her character and plot, since there is less documentation of her life than Katherine Grey’s?

AW: She is mentioned in only four documents – a gift to any novelist, as her life is a blank canvas. But I knew the context of it, as I’ve studied Richard III’s reign over many years. I had to rely a lot on detective work, inference and probability.

NB: Why did you decide to tell their stories in one book, and not write a book on each of them?

AW: The idea for the book evolved gradually. It was originally going to be based on the premise that Perkin Warbeck really was Richard, Duke of York, but I couldn’t make that work, given the source material and the flimsy premise on which he based his claim. I liked the idea of a mystery with a supernatural theme, possibly a timeslip. I wanted to find a new way in which to explore the fate of the Princes in the Tower, and I needed a love story to replace that of Perkin Warbeck and Katherine Gordon. I also wanted to write a sequel to Innocent Traitor. It occurred to me too that writing about Richard III from the point of view of the daughter who loved him would be a novel approach. Eventually, all these ideas came together – after many nights spent lying awake wondering how to meld them!

NB: The character and actions of Richard III loom very large in this book. He fascinates, if not obsesses, people of that time. And

couldn’t it be argued, with the archaeological dig in Leicester, that he fascinates us today? Why is that?

AW: People love a mystery, and they also love conspiracy theories. Yes, Richard fascinates – and many become obsessed, which concerns me. As a historian, I feel I must be objective and not emotionally involved. There is a lot of compelling circumstantial evidence that Richard had the Princes murdered, and that he was a ruthless operator. If there was convincing evidence to counteract all that, I would go with it. But nothing I have read has changed my view.

NB: Do you think that they did indeed discover the body of Richard III this year?

AW: It’s too early to say. The body was in the right place, the scoliosis ties in with the (hostile) descriptions of Richard, and the wounds could be consistent with those he received at Bosworth. I await the DNA results eagerly.

NB: Your view of Henry VII and Margaret Beaufort was not positive in the novel. Have you always thought of them in this way or did research for the book form newer evaluations?

AW: Some see Henry VII as a Machiavellian ruler; it’s trendy nowadays to view Margaret Beaufort as sinister. Historically, I take a different view, but this was fiction, and they are seen from the point of view of Richard’s daughter, so naturally she would find them menacing.

NB: In this novel, you make the women’s behavior consistent with that time, and not necessarily our own. In some historical fiction written today, a 13-year-old girl who wanted to consummate her marriage would be treated as an abused victim but you did not make that choice. Was it difficult to write that part of the book?

AW: No, I just wanted to portray things as they were. Girls were permitted by the Church to be married in childhood and to cohabit at twelve. Life was shorter then. But I was very much aware of modern sensibilities on the subject, and you may have noticed that there are no overtly sexy scenes involving characters that we would deem under-aged.

NB: Can you tell us about your next book?

AW: It’s a biography of Elizabeth of York, and it’s nearly finished. I’ve really enjoyed this project, and have made some surprising discoveries.

STANDFIRST: A DAY OFF SCHOOL FOR AUTHOR AND HISTORIAN ALISON WEIR CHANGED THE COURSE OF HER LIFE

From the University of York's magazine, 2011

When historian and author Alison Weir ‘graduated’ from reading books to reading comics in her early teens, it infuriated her mother. Such was the maternal displeasure that, despite being off sick, the 14-year-old was marched from a doctor’s waiting room to a nearby public library and instructed to ‘take out a book’. But the historian and author, who visited the University recently to deliver a public lecture on Queen Elizabeth I, still remembers that day with fondness, because it was the moment she acknowledges that her life changed forever. When Weir entered that library, she ignited a passion that burns to this day.

She emerged with a spicy for its time - it was the mid 1960s - volume called Henry's Golden Queen, a romantic novel about Katherine of Aragon. It was not perhaps the choice of reading matter her mother had in mind, but it had the desired effect. Comics were forgotten and though Weir says the book was trashy, it was a book – and it was about history.

“It was an adult novel and I simply devoured it,” she says. “It was pretty racy and I thought to myself, ‘Did they really go on like that in those days?’ My passion for history was born overnight and I just wanted to find out more and more.”

Within a year she was researching and writing feverishly - histories, reference works, family trees, plays and novels - but it would be years before she saw any of her efforts in print. Weir studied history at college and trained as a teacher, and then raised a family. Throughout, history was her hobby and she continued writing about it. But she saw little or no chance of escape from her civil service job – the repeated rejection slips from publishers had taken their toll. She admits to being ‘completely demoralised’.

“I kept going for personal enjoyment, and then suddenly I got into print and you could have knocked me down with a feather,” she says.

The years of painstaking research in reference libraries, transcribing chronicles and calendars had finally paid dividends. The result, in 1989, was Britain’s Royal Families and it was based on research that she had started in her teens.

Weir has never looked back and she has now written 15 popular histories while her three novels are all based on historical themes. Both her fiction or non-fiction output rely on extensive research.

“I love the research because you never know what it’s going to throw up. I don’t have expectations – I just clear my mind of any previous ideas about the subject and see where the sources take me,” she says.

The sheer scale of her research is impressive by any measure, but the popular histories that ensue have resulted in criticism in some academic quarters that she is a lightweight. But Weir defends her narrative approach as entirely legitimate.

“I admire academics immensely. Where would we be without them? But I don’t like the occasionally sniffy attitude that a few of them have towards people like me,” Weir says. “There’s no doubt that there’s a certain competitiveness in the historical field, but every book is a contribution to the debate and after all, we all use the same source material. We just present it in different ways.”

Weir’s decision to branch out into writing historical novels “as a sideline” has been an entertaining diversion, though it has also meant that she has had to learn some new skills. Every book, she says, represents a learning curve. Nevertheless, she regards herself first and foremost as a historian.

So what is next? Her next novel - A Dangerous Inheritance - centres on the story of Lady Katherine Grey, the sister of Lady Jane Grey, with a subplot about the Princes in the Tower.

She is also writing a biography of Elizabeth of York, the sister of the Princes in the Tower, who was a pivotal figure at the end of the Wars of the Roses. After the Battle of Bosworth Field and the death of Richard III, Henry VII married her to consolidate his claim to the throne.

York is not unfamiliar territory to Alison – the late Ron Weir, doyen of the Department of History and Provost of Derwent College, was her brother-in-law. She attended a private event in Derwent during her recent visit.

“We have been coming up to York for holidays since my kids were small when we used to housesit for Ron and Alison. It’s a lovely city and I never tire of it.”

INTERVIEW FOR 'THE LADY', U.K., 2012.

What inspired you to study history, and your particular interest in the Tudors?

When I was fourteen, my mother marched me into a library and said, ‘Get a book.’ I chose my first adult novel, Henry’s Golden Queen by Lozania Prole, and devoured it in two days. As historical fiction it was trite, but it sent me off to the history books to find out what really happened – and I’ve been trying to find it out ever since.

As a former teacher, how do you feel about the way history is taught in schools?

I am appalled at the way history is taught in schools. When I was running my own school in the nineties, I realised that textbooks were being dumbed down, and that inaccuracies were common. There seems to be an aversion to teaching pupils the overall sweep of our history. How can you understand the Tudors if you haven’t studied the Middle Ages? And why do educationists fight shy of monarchs, dates and prominent historical figures? We need to know the political framework as well as the social history.

What makes for a good historian?

A good historian approaches their subject objectively, having cleared their mind of all previous perceptions. They trawl exhaustively through original sources evaluating each judiciously. Only then will they look at secondary sources and assess what other historians have written. All historians study the same sources: the fact that history is presented in a ‘popular’ way does not make it less authentic.

Tell us about your next book.

My next book is a novel entitled A Dangerous Inheritance. It tells the stories of Lady Katherine Grey, who was imprisoned in the Tower of London in 1562 by her cousin Elizabeth I; and of Kate Plantagenet, the bastard daughter of King Richard III. Katherine and Kate find out that incurring the wrath of princes is a dangerous game, and that being near in blood to the throne is a curse rather than a blessing. Both young women risk much for love, and to uncover the truth - and both court a tragic fate.

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR

by Helen Greenwood. Edited and corrected version.

(The Sydney Morning Herald, July 2012)

The acclaimed author, who fell in love with history as a teenager, is dedicated to pursuing the truth.

Alison Weir is the No.1-selling female historian in Britain. She has sold more than 2.3 million copies of books on famous figures that include a virgin queen, a serial-marrying monarch and a scandalous duchess. Weir's sales rank her as Britain's fifth biggest-selling historian behind Antony Beevor, Stephen Ambrose, Simon Schama and Peter Ackroyd.

Weir is also down-to-earth, maternal, and laughs as delightedly as a first-time author when I tell her that three generations of women in my family enjoy her books. ''Three people in one family, it's fantastic,'' she says. ''It gives me a huge buzz when people say they've enjoyed my books, because this grew out of a hobby and it's an absolute passion, and it's lovely when I get feedback.''

Weir's passion was ignited when her mother, concerned about her daughter's comic-book reading habits, marched the 14-year-old into a library. Weir randomly plucked out a racy read about Katherine of Aragon - and was hooked.

''I devoured it in two days,'' Weir says. ''For the time, it was rather naughty, and my family was quite straight-laced about those sort of things. I thought, 'Did they really go on like that in those days?' and rushed off to the history books to find out.''

The teenager found the Tudors so compelling she started writing her own history books and then trained as a history teacher. She amassed a home library and filing cabinets filled with research.

She wanted to turn her hobby into a career but her first effort, The Six Wives of Henry VIII, was rejected in 1974 as too massive. ''I got very demoralised because I'd put my heart and soul into it. It was far too long, I know now, but I was very naive then. I did a lot of projects after that and never finished them, but I've still got all the research and I've used a lot of it.'' Weir is not one to give up easily, though, and thought she would have a final try.

Britain's Royal Families was published in 1989 when she had two children and was teaching them at home. Her son had a learning disability and, because the local schools could not cater for his needs, she later set up a private school in her garage for him and others like him. At the same time, she wrote Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses (1995), Children of England: The Heirs of King Henry VIII (1996), Elizabeth the Queen (1998) and Eleanor of Aquitaine (1999). In the past 23 years, she has written 15 popular histories. ''It's a passion,'' she says.

In 2007 she published her first historical novel. Her fourth, A Dangerous Inheritance, is out this month. Like many of her books, it's about women's lives. ''I'm interested in retrieving them from the obscurity to which they've been consigned until recently.

''When I started researching history in the 1960s, a lot of women about whom I've subsequently written were actually footnotes to history. There was a perception that women weren't important. And it's true, women were seen historically as far inferior to men. It's only in very recent times that women have become emancipated, and it's interesting to be able to focus on them at last, because they were virtually ignored unless they were famous, like Elizabeth I or Eleanor of Aquitaine.''

In A Dangerous Inheritance, the heroines aren't famous but have fascinating stories. One is Kate, the illegitimate daughter of Richard III. The other is Katherine Grey, the sister of the ill-fated Lady Jane Grey, who was England's queen for nine days.

The two Katherines are linked by history's most famous unsolved mystery, the disappearance of the young Princes in the Tower, and by having forbidden lovers.

A Dangerous Inheritance is Weir's most ambitious historical novel to date. Though it stands alone, it can be read as a sequel to her first novel, Innocent Traitor, the tragic story of the accomplished Lady Jane Grey, propelled to the throne after the death of Henry VIII's son, Edward.

The Tudors have gripped our imagination for centuries and Weir is no exception. She gives talks and takes tours and explains why that period fascinates her.

''These are are larger-than-life, dynamic characters about whom we have a lot of information, and there are dramatic events,'' she says. ''There are six [royal] wives, two of whom are executed. There are three annulments, a queen for nine days who is beheaded at the age of 17, and you've got the first female ruler as well.''

The spread of literacy during Tudor times left a rich historical legacy. ''We have this incredible, documented record of royal private lives that fleshes out the characters and makes them become so real,'' Weir says. ''We also have an incredible visual record, for example, the portraits of Hans Holbein, so we can see for the first time what people really looked like.''

Then there are the remains of those splendid palaces dotted throughout England. ''It's an age of magnificence. Power attracts, power is sexy, and these are the outward manifestations of power. It's very, very exciting. There's so much documentation of this period, so much visual evidence.''

Understandably, she gets peeved when books and films and television dramas get the facts wrong. But does it really matter that there is the wrong kind of costume in the top-rating, sexy TV series The Tudors, or the wrong kind of dog in the lovingly dramatised Elizabeth: The Golden Age?

''I don't think it matters that there is the wrong kind of dog,'' Weir says. ''What matters is when they get the really big things wrong. Sir Walter Raleigh, as played by Clive Owen, for example, [defeating] the Spanish Armada almost single-handedly when he wasn't even there. I was asked to review it by The Guardian and I took my mother, who is a film buff. She had to tell me to shut up and stop laughing.''

Film is a powerful medium and people learn to accept errors as facts, she says. ''The first Elizabeth film was an absolute travesty historically. It really was sloppy. As for The Other Boleyn Girl and The Tudors, people's perceptions are distorted because of these. It matters to me as a historian, because I spend my life trying to get it right, although I don't get it right on every occasion. When we see a very romanticised view of Henry VIII's wives, this is seen as history, and so it becomes history.''

By comparison with the well-documented Tudor period, she says, the mediaeval era is harder to write about. ''Right at the end of it, you get the invention of printing but we haven't got the documentation about the private lives of monarchs. We've got some, but nowhere near the extent we have about the Tudors.''

As a historian, Weir has successfully overcome these obstacles. It took eight years for her to convince her publishers she could produce her brilliant biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine. ''They said, 'How can you write a biography on a woman who has been dead for 800 years in the same way you can write one on the wives of Henry VIII or Elizabeth I?'

''There is the source material, but it's more fragmentary. It's a different kind of biography. I put forth the evidence and try to infer what I can from it. Beyond that, you're in the realm of speculation.''

Taking a stab in the dark is second nature to Weir, who was a dreamy child with a vivid imagination that used to get her into trouble. ''I'd scare myself a lot. I used to read ghost stories, I was fascinated by them, and I knew they'd frighten me and of course there I was at night wailing and my mother saying, 'You're not reading them' when she found them.

"I'm still very imaginative but when one writes history, one has to keep within the confines of historical research.''

These restrictions made her itch to get inside the heads of her subjects and write historical fiction. ''Having the freedom to think about their motives, emotions, reactions and how they got from A to B is liberating,'' she says. ''But there are still constraints because what they do and what they say must be in the context of what is known about them historically.''

After all these years, Weir is still the teenager who fell in love with history. ''If people really want to know and learn from history, why do they want bad history? Why don't they want good history? Wouldn't you prefer to know the truth, rather than the legend?''

The Booktopia Book Guru asks Ten Terrifying Questions (2012)

(Alison Weir on the Lancaster and York Tour 2013)

To begin with why don’t you tell us a little bit about yourself - where were you born? Raised? Schooled?

I was born and raised in London, U.K., and educated privately, but my interest in history stems from independent study, although it was my specialist subject at teacher training college.

What did you want to be when you were twelve, eighteen and thirty? And why?

At twelve, a ballet dancer, because I was in love with the romance of it. At eighteen, a teacher – I’ve always loved working with children. At thirty, I wanted to be a mother and a published author, in that order.

What strongly held belief did you have at eighteen that you do not have now?

Too many to mention! I was a very opinionated teenager.

What were three works of art – book or painting or piece of music, etc – you can now say, had a great effect on you and influenced your own development as a writer?

There are too many examples to mention, but three stand out. The book was Antonia Fraser’s Mary, Queen of Scots, which set a new standard in historical biography. The painting was the portrait of Anne Boleyn in London’s National Portrait Gallery – it intrigued me, much as Anne always has. The music was the Pavane la Bataille by David Munrow and the Early Music Consort of London, which instantly transported me back to the magnificence of sixteenth-century courts. Annihilating!

Considering the innumerable artistic avenues open to you, why did you choose to write a novel?

I was already a published historian. I’d written lots of novels when I was young, and wanted to see if I could still write one. I wrote it just as a leisure project, but quite liked it, so I showed it to my agent. That’s how I became a published novelist.

Please tell us about your latest novel…

A Dangerous Inheritance is the stand-alone sequel to Innocent Traitor, that first novel. It tells the story of two beautiful, tragic heroines, linked both by kinship and by supernatural bonds.

In her short life, Lady Katherine Grey has already suffered more than her fair share of tragedy. Eight years before, her older sister, Lady Jane Grey, was beheaded for unlawfully accepting a crown that was not hers. And Katherine suffered too, as a result of Jane`s fall... Now she has defied her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, by marrying a man who is forbidden her.

Intertwined with Katherine's story is that of her distant kinswoman, Kate Plantagenet, the bastard daughter of King Richard III. In 1483, Kate is brought to London for the coronation of her cousin, King Edward V, and her world changes dramatically.

Kate loves her father, but all is not well at court, and soon after her arrival, she senses sinister undercurrents and hears terrible rumours that deeply disturb her. Soon, she embarks on what will prove to be a dangerous quest, covertly seeking information that can throw light on what would become one of history's most enduring mysteries. But time is not on Kate`s side - or Katherine's either.

Katherine and Kate find out that incurring the wrath of princes is a dangerous game, and that being near in blood to the throne is a curse rather than a blessing. Both young women will risk much to for love, and to uncover the truth - and both will court a tragic fate.

What do you hope people take away with them after reading your work?

A sense that they have read about authentic history in an authentic setting – and also that they will have enjoyed the experience and gained new perspectives.

Whom do you most admire in the realm of writing and why?

I admire many writers for many different talents. My favourite novelist is the late Norah Lofts, whose work I admire for the integrity of her writing, her characters, her insights, and the sinister undercurrents in her books. I own all her books, and it’s always a joy to re-read them.

Many artists set themselves very ambitious goals. What are yours?

To publish all the research I’ve done over the years. I’m near to achieving that goal.

What advice do you give aspiring writers?

Never give up!

BRITISH WEEKLY INTERVIEW, U.S.A., 2012

When did you get the idea for your book? How did you get the idea?

I had long wanted to write about Lady Katherine Grey, whose story is so poignant, but I wanted to add a twist to the story – and I wanted to include a mystery with a supernatural element. The Tower of London provided inspiration, as Katherine was imprisoned there; and her story called to mind that of the Princes in the Tower, who had probably been murdered there eighty years earlier on the orders of Richard III. I thought about ways to approach that subject, and it occurred to me that there were parallels between Katherine Grey’s story and that of Richard’s bastard daughter, Katherine Plantagenet. Hence my two storylines – the entwined tales of these two tragic girls, each of whom have good reason to need to discover what really happened to the Princes.

What's the most surprising or unexpected thing that happened while writing or promoting this book?

Sir Thomas More, who wrote a controversial book about Richard III, and described how the Princes were suffocated on his orders, probably obtained much of his information from several ladies living in the Minoresses’ convent (‘the Minories’) near the Tower. Decades later, in my novel, Katherine Grey tries to track these ladies down and find out what they knew. It was amazing to discover, when reading an old book on the Minories, that after the dissolution of the monasteries it had come into the possession of Katherine Grey’s father and that she had lived there for some years of her childhood. That was an exciting coincidence – one I had not thought to find – and a tangible link between my characters.

What research did you do for this book?

My novels have all been based on research I have done over many years, and I know the Yorkist and Tudor periods very well, but I had not written to any extent on Katherine Grey, so I did have to do some original research on her. As for Katherine Plantagenet, she is only mentioned in four sources, so her life is a blank canvas – a gift to a historical novelist. The fate of the Princes was the subject of my book, The Princes in the Tower, and I followed that closely for the chapters relating the heroines’ quests to discover their fate.

If you viewed documents where did you go and how did you find them?

A lot of the sources I use are in print or online now, but I have researched from documents in the National Archives, the British Library or local archive offices.

What other books or other writing have you done?

Next year I’ll be publishing my twentieth book, a biography of Elizabeth of York. Sixteen of those books are non-fiction, mostly on kings and queens or women’s histories.

Have you won any awards for this book or other books?

My biography of Eleanor of Aquitaine won the U.K. Good Book Guide award for the best biography of 1999, as voted for by readers in 100 countries.

Who’s your editor?

Susanna Porter is my commissioning editor at Ballantine.

What's the most challenging part for you working with your publisher?

Not being able to get together with her to discuss the editorial process as often as I would like, as I value her advice and her creative input. But I’m in London and she’s in New York. It’s always a pleasure to get together and bounce ideas off each other.

How did you meet them and what's their editorial process?

I first met Susanna when she came to London and we had tea together. I liked her enormously, and have enjoyed working with her over the years. I’ve always had a strong sense that she really cares about my work. She is always very supportive. She and my U.K. editor pool their ideas on each new book, then my U.K. editor and I get together to discuss them. I do whatever is agreed, then Susanna may come back with further suggestions. The copy-edit is done in the U.K. as well, but I usually get a short list of queries from Ballantine to ensure that the book meets the requirements of the American market.

Who’s is your agent?

Julian Alexander of Lucas Alexander Whitley in London. He’s been my agent for twenty-five years now, and I can only say that I made a very good choice!

How did you find your agent?

I was recommended by a publisher who rejected a book but thought that my work had potential.

What are you currently working on now?

A biography of Elizabeth of York, queen of Henry VII and mother of Henry VIII.

Do you have a website? Twitter? Facebook? Upcoming book signings or events?

I have a website for my books – www.alisonweir.org.uk – and another for the historical tours I run: www.alisonweirtours.com, both of which I maintain myself. I use Facebook fairly regularly, and Twitter occasionally. As well as writing books and planning and leading tours (next year we’re running ‘Lancaster and York’ and ‘The Six Wives of Henry VIII’), I do a busy programme of events – I’ve had to cut them down from 67-69 a year to about 45, as I’m so busy. But I do enjoy them. I love meeting fellow history enthusiasts.

Is there anything else you'd like to add?

Just that I feel very lucky to be a published author, and that I’m still pinching myself!

A DANGEROUS INHERITANCE

by ALISON WEIR

In this Jubilee year, the royals are at their most popular, and even a year on from William and Kate’s wedding, all eyes are still on the heirs to the throne, who visibly bask in the Queen’s approval. But it wasn’t always this way – and this is the main theme of my new novel, A Dangerous Inheritance, which tells the story of two young women who lived in an age in which royal heirs who were perceived as a threat to the monarch were swiftly dealt with. The two female heroines, Lady Katherine Grey and Katherine Plantagenet, are linked in more ways than one, but mainly because they are both in danger for being too close in blood to the throne.

Katherine Grey was cousin to Queen Elizabeth I. In 1562, at a time when Elizabeth’s throne was by no means secure, Katherine dared to marry in secret and produced a child who might live to challenge the Queen’s title. Inevitably, she ended up in the Tower, in peril of death.

Katherine had already suffered tragedy. Eight years before, her older sister, Lady Jane Grey, had been beheaded for treasonously, if unwillingly, accepting the English crown and reigning unlawfully for nine days. Katherine was a victim of Jane`s fall, for her brief but happy first marriage, to Henry, Lord Herbert, was speedily dissolved; his father did not want his line tainted by association with a traitor. He had not even allowed the young couple to consummate their union, envisaging, correctly, that things might go very wrong for those who had put Lady Jane on the throne.

Katherine felt the parting from her husband keenly, and for many years she hoped that they might be reunited, but it was not to be. Then she met Edward Seymour, nephew of Queen Jane Seymour (Henry VIII’s third wife), and fell in love headily - and disastrously. For Katherine was the heir to Elizabeth`s throne, and the Queen was jealous: she would not tolerate a rival, and had forbidden Katherine to wed. Katherine’s folly in marrying secretly for love, and producing a son, was anathema to the Virgin Queen, who denied herself the comforts of marriage for political and, probably, psychological reasons. But Katherine’s love for Edward was the overriding passion of her life, and she was to remain staunchly faithful through every trial, until her death.

Katherine Grey’s tale is interwoven with that of a spirited, beautiful girl who lived eighty years earlier. The two are linked by marriage and (in the novel) supernatural experiences.

Katherine Plantagenet, the bastard daughter of King Richard III, is known to history only through four grants relating to her marriage to William Herbert, Earl of Huntingdon. From this and from circumstantial evidence and credible inference, I have recreated her story. Thus the narrative flashes back eighty years, to 1483, when thirteen-year-old Kate Plantagenet is brought to London for Richard’s coronation. Kate loves her father, but soon after her arrival at court, she senses sinister undercurrents. King Richard has gained his throne by disinheriting and deposing his nephew, the young King Edward V, and has imprisoned the former King and his brother, the Duke of York, in the Tower of London. Before long, Kate hears appalling rumours that her father has had the two Princes in the Tower murdered. This throws her into turmoil: Like many people at the time, and since, she wants to know the truth about the Princes’ disappearance.

Writing about Richard III from the viewpoint of a daughter who wanted to believe the best of him proved a challenging experience, because in 1992 I published a book entitled The Princes in the Tower, in which I investigated the ancient but still highly controversial mystery of their disappearance, and concluded that the evidence strongly suggests that Richard III did order their murder. In this novel, my aim was to present him in a more positive light, through the eyes of the daughter who loved him.

Hoping that she will be able to prove that her father has not shed the blood of innocents, Kate embarks on what will prove to be a dangerous quest. But time is not on her side.

Meanwhile, in the Tower, Katherine Grey becomes increasingly perturbed by eerie dreams and phantom voices, and wonders if these manifestations are somehow related to the disappearance of the Princes in this very fortress, eighty years before. Katherine’s interest in the mystery is emotional, bound up with her fears for her baby son, who is too near in blood to the throne for comfort – just like the Princes. And so, with the help of her kindly gaoler, Sir Edmund Warner, she too sets out to find the truth. The evidence the two girls uncover is based on fact, although I had to take into account which sources would have been available to them in 1483-5 and 1562.

Katherine Grey’s sojourn in the Tower was relatively comfortable. Warner was a sympathetic custodian and allowed Edward Seymour to visit Katherine, with the result that she fell pregnant again, with grievous consequences. Time was not on her side either.

A constant theme in the novel is the danger of being too close in blood to the throne. Katherine Grey was Elizabeth’s heir, but it’s unlikely that she wanted to supplant the Queen; rather, she wished to be acknowledged as her successor, which Elizabeth would not do. It is possible that Katherine’s head was so turned when she saw her sister Jane made queen that for ever after her ambitions were focused on wearing a crown. In my view, she was a naïve girl who let her heart rule her head and did not think things through logically. Her instincts were emotional rather than rational. Because of that, she ended up out of her depth, in deep trouble.

The fictional Kate Plantagenet is not Richard III’s heir, but after he is defeated at the battle of Bosworth by Henry Tudor, her kinship to the fallen monarch is a threat to the usurper, now Henry VII, and to her husband, who no longer wants to be married to the daughter of a king who has been branded a tyrant. Continuing the theme, by their very existence, the historical Princes in the Tower remained a threat to Richard III after he declared them bastards and had Edward V deposed. Plots in their favour convinced him that he would never be secure on his throne while they lived.

Elizabeth I had grown up in the shadow of the Tower: her mother, Anne Boleyn, had been executed there for treason, as had others who were close to Elizabeth; and she herself was imprisoned there at twenty, daily expecting to be executed for her suspected involvement in a rebellion to put her on the throne in place of her sister, Mary I. Elizabeth too had known the stain of bastardy, and how easy it was to become the focus of others’ plots, which had been the fate of the executed Lady Jane Grey.

Fortunately, we live in more enlightened times: the last royal to suffer execution was Charles I in 1649, and since Tudor times the succession to the crown has never been so disputed. Unlike Elizabeth I, Lady Jane Grey, the Princes and my two heroines, young royals today do not have to endure danger and tragedy because of the blue blood that runs in their veins. For them, mercifully, it is no longer a dangerous inheritance.

MINORESSES’ CONVENT, ALDGATE

This religious house, known more commonly as the Minories, features prominently in the book.

(The illustrations show the ruins of the Minories in the late eighteenth century. No trace of it remains today.)

The house of the Grace of the Blessed Mary was founded outside Aldgate in the parish of St. Botolph in 1293 by the brother of Edward I, Edmund earl of Lancaster, for enclosed nuns of the order of St. Clare, or Minoresses, as they became known. The first members of the convent were brought to England by the earl's wife Blanche, queen of Navarre, probably from France.

From the earliest foundation the house enjoyed important privileges, but the house seems at first to have been richer in privileges than in revenue. Later they were granted financial exemptions, which may possibly reflect the nuns' poverty, and powerful influence exerted on their behalf, since the house always had a particular attraction for persons of rank. John of Gaunt, for example, bequeathed £100 to be distributed among the sisters.

From the time of Margaret de Badlesmere, who was living in the nunnery in 1323, well born widows found a retreat from the world at the Minories. Relations between the nunnery and the family of Edward III’s son, Thomas de Woodstock, Duke of Gloucester, appear to have been of the closest kind. His house adjoined the conventual church, and the abbess and sisters allowed him to make a door between the two buildings so that he could enter the church as he pleased. His Duchess died in the nunnery, and one of their daughters, Isabel, who had been placed in the nunnery at a very youthful age, chose to remain as a nun, and became abbess.

This connection with the royal family accounts for the favour shown to the Minoresses by Henry IV, who confirmed privileges granted to them by his predecessors, and decreed that no justice, mayor, or other officer should have any jurisdiction within the precinct of the house except in the case of treason or felonies touching the crown. In 1461 Edward IV granted the Minoresses property 'on account of their poverty'. It was within the convent precincts, ‘in the great house within the close’, that several ladies chose to live apart from the world at the turn of the sixteenth century; and it may be that with them lay the evidence of what really happened to the Princes in the Tower. And at that time the convent enjoyed the charity of Elizabeth of York, who was related to the Abbess.

In 1515 twenty-seven of the nuns died of some infectious complaint, so that there could hardly have been less than thirty or thirty-five before the outbreak. The abbey was dissolved in March, 1539. The old convent buildings were destroyed in a fire in 1797, and their remains demolished.

DVD EXTRAS!

This book, originally titled Innocent Blood, contains two intertwined stories. The original text - at 642 pages - was thought to be too long, for commercial reasons (the book would have had to be priced higher), so over 140 pages have been cut by the author during the editing process. However, to give readers a flavour of the book, some of the cut passages now appear here. The first is a scene that takes place in June 1483. Kate is Katherine Plantagenet, the illegitimate daughter of Richard, Duke of Gloucester (the future Richard III), and she is planning an adventure...

Pleading that she was hot and needing to go indoors to get a drink, Kate sought out Mattie, finding the little maid in her bedchamber, mending a hem.

‘I want to go to Westminster,’ she said. ‘Will you come with me?’

‘Why, mistress?’

‘I want to see the palace and the abbey,’ Kate told her, ‘but it’s a secret. I don’t want the Duchess or my father to know I have gone there.’

Mattie grinned broadly. ‘You can trust me, my lady,’ she said. ‘And it sounds to me as if there’s more to this than just sight-seeing.’

‘There is!’ Kate confirmed.

‘Well, I’m always up for an adventure,’ Mattie said, hanging the mended dress on a peg. ‘Let me just use the privy, and I’ll be with you.’

Kate told the Duchess that they had decided to go shopping in Cheapside.

‘Again?’ Anne said, smiling. ‘It’s a good thing your father gives you a generous allowance! Enjoy your afternoon.’

They hastened down to St Andrew’s Hill and caught a boat at the water-gate there. The boatman was garrulous, grumbling about the press of traffic in the river and the stinginess of his previous customer, who hadn’t tipped him, and he also had a deal to say about the Duke of Gloucester. Kate sat tight-lipped as he predicted, mark his words, that the Duke was bent on seizing the throne.

‘How do you know that?’ Mattie asked, sensing Kate’s anger.

‘’S common knowledge. Stands to reason. He had Lord Hastings put to death, and sure it is Hastings was murdered because of the truth and fidelity he bore to the King. And look at the poor Queen, in sanctuary and in fear for her life. I don’t know. What is the world coming to?’

Kate was hard-pressed to keep her mouth shut, but Mattie was never reticent. ‘That’s all rubbish,’ she declared. ‘The Duke is my master, and I could never find a kinder. Don’t believe all the nonsense put about by his enemies!’

The boatman looked as if he was about to retort, but changed his mind, and the rest of the journey passed in silence. When the two girls alighted at the stairs below the King’s Bridge at Westminster and paid their fare without any extra, he stuffed the pennies in his leather jerkin and rowed off without a word.

‘That shut him up!’ Mattie said.

‘I am really grateful to you,’ Kate told her, ‘and I know my father the Duke would be proud of your loyalty.’

‘It’s nothing,’ Mattie replied, but she was pleased - you could see it in her face.

Kate had never been to Westminster, and when she passed through the great stone gateway by the river, she was awed at the huge complex of stately buildings surrounding her. But it was disconcerting to see the place swarming with soldiers. There was a long armed chain of them encircling a massive church that Mattie said was Westminster Abbey, and all were armed with swords and staves. Crowds of people were standing at a safe distance, watching, held back by more armed men. Kate was already beginning to wonder if she had been foolish to come here, when not a stone’s throw away she saw a large group of lords, conferring among themselves; among them was a short man in black, who had his back to her, and immediately she recognised her father.

‘Quick!’ she whispered. ‘He mustn’t see me!’

She grabbed Mattie’s arm and pulled her into the shelter of a doorway, then, realising that it was a cookshop, hastened inside. They would be inconspicuous in here. The place looked reasonably clean, and smelled deliciously of baking bread and roasting meat – although these aromas could not quite mask the whiff of unwashed bodies and stale sweat. Resolutely ignoring that, she quickly purchased two small hot manchet loaves filled with slices of steaming roast beef, and sat down with Mattie at a table away from the window to eat them. From here, they had a good view of what was going on just across the road. There were many men in armour milling about, so sometimes the view was obscured, but they were able to observe the Duke conferring with a very elderly man in the red silk robes of a cardinal, then saw the venerable father nod, bow and make his way towards the far end of the abbey, where he turned a corner and disappeared; with him went many important-looking lords and clergymen.

‘The sanctuary’s up there,’ Mattie said. ‘Just off Thieving Lane. It’s aptly named, for most of those who seek sanctuary are robbers and cut-throats; the Queen is in poor company.’

‘She’s not in the common building,’ Kate told her. ‘The Duchess told me she is lodged in the Abbot’s house.’ Mattie snorted at that. She had no love for the Queen.

The Duke and his colleagues, amongst whom Kate recognised the Duke of Buckingham, remained where they were, their restlessness betraying their impatience. Kate had been shocked to see so many soldiers here, even though she guessed they were there to preserve her father’s safety. All this for the sake of one small boy, though! If only the Queen wasn’t being so stupid and difficult.

Nothing was happening, so Mattie took the opportunity of pointing out Westminster Hall, a magnificent building across the way, and the King’s great palace beyond it. ‘That tall building is St Stephen’s Chapel,’ she said. Kate had heard the Duchess Anne speak of it several times.

‘That is where my lord father and the Duchess were married,’ she told Mattie. Then she paused, troubled, because she was coming to realise that there had been a growing coldness between her father and stepmother of late, a coldness that had never been evident at Middleham. It had begun, she was certain, on that evening when her grandmother had been present, and her father had shouted at Anne after Anne had questioned the legality of his proceedings. Since then, Anne had held herself a touch aloof from him, observing the proper courtesy due from a wife to her husband, but little of her former warmth. Yet surely Anne could not but approve of the measures the Duke had taken to ensure his safety and prevent the Wydevilles from seizing power? Not so long ago she had been in desperate fear for him, but now it seemed as if she was doubting him and paying heed to vicious gossip, which was not like her; and Kate was sure there was something that Anne was not telling her. Dare she ask her what it was? It might not be seemly to touch upon such personal matters.

‘Penny for them, mistress!’ Mattie giggled.

‘Oh, I’m sorry,’ Kate apologised, and fixed her gaze on the scene beyond the window, which had not changed.

A man waiting at the counter began loudly voicing his opinions. ‘Seen what’s happening out there?’ he asked the cook. ‘That’s the Duke of Gloucester, come to fetch the little Duke of York from sanctuary. He’s sent in the Cardinal to get him out. If you ask me, the Cardinal is here to make sure the Duke’s men don’t violate the sanctuary.’

‘Some hope then,’ replied the cook, a beefy, red-haired man in a stained apron. ‘What could one old man do against all those soldiers.’

‘I’ll wager you, if the Queen won’t give up the boy, Gloucester will send in the soldiers and force her to. Why else has he brought them?’

Kate had to speak up. ‘Because the Marquess of Dorset is at large, and wishes him ill,’ she said stoutly.

‘My, you’re a well informed young lady,’ the man retorted, and the cook and his other customers laughed. ‘But you must be the only person in London who doesn’t suspect the ambitions of the Duke.’

Kate sat down, reddening, knowing that she dared not declare her identity here. She sat there unspeaking, furious with the man, and with herself for speaking out.

‘Cat got your tongue, has it?’

‘Best not to say anything, mistress,’ Mattie murmured.

Kate nodded, and looked out again, resolutely ignoring the guffaws of the men at the counter. At length, they lost interest in her and returned to their talk.

‘It wouldn’t be the first time Gloucester’s violated sanctuary,’ a middle-aged man said. ‘Remember Tewkesbury? He had the Duke of Somerset and other Lancastrians dragged out of the abbey to summary execution. Saw it myself: I served on that campaign. There was no trial, nothing. The Duke said it was his right as Constable of England.’

Kate froze. She was remembering her father’s words at table. I am not a sanctuary breaker. Surely, he had had every right to apprehend those men who had sought sanctuary at Tewkesbury? But she knew very little about the privileges he enjoyed as Constable of England, so she kept her mouth firmly shut. If he had said he had the right, then he must have had. Yet she could not help recalling that the Duchess had seemed to be unconvinced, and she remembered wondering if Anne knew something that she did not. Anne, she was aware, had then been on the Lancastrian side; her father Warwick had married her to Henry VI’s son, Edward of Lancaster, but Edward had been slain at Tewkesbury; it stood to reason that Anne would then have been willing to believe all the calumnies about the Yorkists that must have been circulating afterwards.

Something was happening at last. A cleric came hurrying from the direction of the sanctuary, bowed to the lords, and spoke to Gloucester. He then beckoned the rest, and led them off towards the palace, where they disappeared into Westminster Hall. Then the Cardinal and his party emerged from the sanctuary, and with them they had a small, fair-haired boy. Kate knew that it was her cousin, the Duke of York. She had never met him, but she could see that he was a beautiful child, and that he seemed quite merry, skipping along beside the elderly primate. Certes, her father had been right, and the boy was no doubt delighted to be out of sanctuary and away from the cloying company of his mother and sisters.

The Cardinal led his charge into Westminster Hall, and then the soldiers began to disperse, only a few remaining on duty near the sanctuary. The crowds evaporated too, now that there was nothing more to see, and Kate and Mattie got up to leave. There was no point in staying, and Kate wanted to be home before her father returned.

Kate's story is interlaced with that of Lady Katherine Grey, the younger sister of Lady Jane Grey. One of the story threads about Katherine, which appeared at intervals throughout the book, has been cut, but appears in part below.

I recall in painful detail – how could I not? - the day I finally left my prison. They had to drag my little boy from my arms, I screaming and wailing, and the child roaring with fear and fury.

‘He is to go with his father,’ they said, and carried off the yelling child. He was but two years old! And I have never set eyes on him since.