Miscellany

A WRITER'S LIFE IN LOCKDOWN

Article for the 125th and final issue of the City of London School for Girls Olds Girls' Asociation

KATHERINE OF ARAGON AT CROYDON PALACE

It is often stated that Henry VIII’s first queen, Katherine of Aragon, lived At Durham House, the Bishop of Durham’s palace on London’s Strand, after the death of her first husband, Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales in April 1502. In fact, Henry VII gave the young widow - she was sixteen - the choice of two residences: Durham House and Croydon Palace, the Archbishop of Canterbury’s residence in Surrey. Katherine chose Croydon and, by 4 May, was lodging there.

At that time, Croydon Palace was a large, stately courtyard house with opulent chambers, a great hall, a chapel and a great parlour. There had been archiepiscopal buildings on the site since the tenth century. Since the archbishops used the palace as a summer residence, Katherine was probably accommodated in their own chambers, which had recently been partially rebuilt.

Late in May, the Queen, Elizabeth of York, sent her page, to Croydon, possibly to check on the Princess’s health, and perhaps discreetly to ask her servants if there were signs of any pregnancy.

During the months Katherine stayed at Croydon, her future remained under discussion. Her parents, the Spanish sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella, were naturally concerned about her. On 10 May they had sent an ambassador to England with instructions to preserve their alliance with Henry VII, ask for the immediate return of Katherine and her dowry and, if possible, secure the Princess’s betrothal to the new heir to the throne, Prince Henry, who, at eleven, was five years her junior. Everyone was aware that, if Katherine had conceived a child by Arthur, her union with Henry would contravene canon law. Doña Elvira, her duenna, was adamant that the marriage had not even been consummated and wrote to Queen Isabella insisting that the Princess remained a virgin. In July, when it was beyond doubt that Katherine was not pregnant with Arthur’s child, Isabella informed Henry VII that her daughter remained a virgin. But, although Henry also wished to preserve the Spanish alliance, he was hesitant. Months would pass before he reached a decision on the proposed betrothal between Katherine and Henry. Meanwhile, with her future still uncertain, Katherine had moved to Durham House; she was living there by 6 November 1502.

Her stay at Croydon must have been shadowed by sorrow and anxiety. All her life, she had been brought up as a future queen of England; now that destiny had been stolen from her. It would be seven long, stressful, penurious years before it was restored to her and she became Henry VIII’s first wife.

The Old Palace is now a school and I know it well because my daughter was a pupil there.

You can read my article on the portraits of Margaret Beaufort here at Art.UK: https://artuk.org/discover/stories/my-lady-the-kings-mother-images-of-margaret-beaufort

Beyond the Tower Walls (2020) - you can listen to the webinar here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p7D2xWZAltw&feature=youtu.be

In October 2015 I was privileged to be invited to the Royal Courts of Justice in the Strand to speak at the City of London's annual Quit Rents Ceremony, an ancient ritual that dates back to the Middle Ages and takes place in the Lord Chief Justice's Court in the presence of the Queen's Remembrancer, the only surviving officer of the Court of the Exchequer. This was a very special event for me, as my links with the City go way back to the years when I was a pupil at the City of London School for Girls. The speech I gave is below:

THE LOST ROYAL HERITAGE OF THE CITY OF LONDON

Before the Great Fire of London, the City of London boasted several royal residences and burial places. Today I am going to tell you about some that I’ve researched for my books, but which have mostly disappeared.

In Newgate Street stand the ruins of Christ Church, a stark reminder of the devastation caused by the Blitz of the Second World War. This is the site of Christ's Hospital, the Blue Coat School founded by Edward VI in the sixteenth century, destroyed during the Great Fire of 1666 and rebuilt by Sir Christopher Wren. Yet these ruins stand on the site of an even older foundation, the magnificent monastery of the Grey Friars, originally founded in 1225.

Two French-born queens, Margaret, the second wife of Edward I, and Isabella, the wife of Edward II, had a special affection for this church and the Franciscan Order. Margaret asked for the new church to be modelled on the lines of the Church of the Cordeliers in Paris, which had been founded St Louis, King of France, around 1250, and there was a chapel dedicated to St Louis at Newgate. Isabella paid handsomely towards the completion of the church, which, when finished in 1348, measured a grand 300 feet long by 89 feet wide, making it second only to St Paul's Cathedral in size. It was a beautiful light and spacious building, and thanks to the patronage of these two queens and other royal ladies, it remained the most prestigious Franciscan house in England, and the most fashionable church in London, for the next two centuries.

In the fourteenth century, this was a royal mausoleum set to rival Westminster Abbey as the resting place of crowned heads, yet tragically its splendours, including the tombs of Margaret and Isabella, are long gone, having disappeared after Henry VIII dissolved the monastery in 1538, during the Reformation. Isabella was – undeservedly, I think - one of most notorious femmes fatales in history. Popular legend has it that her angry ghost can sometimes be glimpsed amid the ruins, clutching the heart of murdered husband to her breast. But if he was murdered – and that’s another story – it’s unlikely that she was involved.

Nearby once stood the ancient collegiate church and monastery of St Martin le Grand, founded around 1056 in the reign of Edward the Confessor. It was within the City, but was not subject to its jurisdiction, being a liberty with the privilege of sanctuary. St Martin’s was responsible for the sounding of the curfew bell in the evenings, which announced the closing of the City's gates. The monastery was dissolved by Henry VIII and demolished in 1548.

In 1472, Edward IV’s brother, Shakespeare’s ‘false, fleeting perjur’d’ Duke of Clarence, hid away his wife’s sister, Anne Neville, as a kitchen maid in his London house, the Erber, to prevent his brother, the future Richard III from marrying her and securing her inheritance, which Clarence wanted for himself. But Richard tracked her down, rescued her and placed her in the sanctuary of St Martin le Grand until their marriage could be arranged. Another who sought sanctuary here was Miles Forrest, one of the reputed murderers of the Princes in the Tower. Here, according to Thomas More, Forrest ‘rotted piecemeal away’ and died within a year.

John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, fourth son of Edward III, was the mightiest magnate in England, but in 1381 his great palace of the Savoy on the Strand was burned down during the Peasants’ Revolt. By 1391 he had leased Ely Place in the fashionable suburb of Holborn, just beyond the City boundary. But for centuries the Bishops of Ely lent their hall for the festive gatherings of the newly-elected serjeants at law.

Since 1286, Ely Place had been the town house of the bishops of Ely. There has been a building on the site since the sixth century, and parts of the walls that survive today date from the 1100s, being eight feet thick. To the north of the palace site is Bleeding Heart Yard, the name of which has nothing do with John of Gaunt but commemorates a murder in 1626; and to the west is Ely Court, where lies the Mitre Tavern, founded in 1546. Outside is a cherry tree around which Queen Elizabeth was said to have danced.

Recently rebuilt above the remains of the older house, the property leased by John of Gaunt was a large and imposing palace with 'commodious rooms'. Its extensive gardens were famous for their roses and strawberries, the latter being mentioned in Shakespeare's Richard III; there was also a vineyard. A massive stone gatehouse adorned with the Bishop's arms fronted the street.

Within the palace complex was the bishops' magnificent private chapel, dedicated to the Saxon St Etheldreda and completed around 1300. A Catholic church since the 1870s, it was extensively rebuilt both before and after suffering severe bomb damage during the Second World War, but the crypt survives from John of Gaunt’s time - all that is left of the great palace that remained his London residence for the rest of his life.

In the late sixteenth century Elizabeth I forced the Bishop of Lincoln to surrender Ely Place to the Crown. Sir Christopher Hatton then acquired the freehold – hence the name of the nearby street, Hatton Garden. The old palace was demolished in 1772, when the present Ely Place – a gated cul-de-sac of Georgian houses – was built. It incorporates the church of St Etheldreda.

Old St Paul's Cathedral, which was destroyed in the Great Fire of 1666, was the largest building in mediaeval England. It was completed in 1220, on the site of an earlier church founded around 607 by King Ethelbert of Kent, which burned down in 1087. The new stone cathedral in the Romanesque style was truly awe-inspiring: the steeple was 520 feet high and the spire was 260 feet. The church was 720 feet long and 130 feet wide. Thus it was longer than the present St Paul's, and its spire taller than that of Salisbury Cathedral, the highest in England today.

The interment of Blanche of Lancaster, the first wife of John of Gaunt, in 1368, was the first royal burial in St Paul's since that of the Saxon King Ethelred the Unraed in 1016; in Gaunt's day, Ethelred’s massive stone sarcophagus could still be seen in the north quire aisle. Behind the high altar stood the magnificent shrine of St Erkenwald, a seventh-century Bishop of London.

In 1399 John of Gaunt himself was buried in Old St Paul’s Cathedral. His body was brought from Leicester to the Church of the Carmelites, south of Fleet Street. Today, an inn, the Old Cheshire Cheese in Wine Office Court, stands on the site of the Whitefriars' guesthouse where his widow, Katherine Swynford, may have lodged. On Passion Sunday, in the presence of King Richard II and all the nobility, Gaunt was laid to rest with great honours beside Blanche in an 'incomparable sepulchre' near the high altar. During the Wars of the Roses the tomb was defaced and the painted alabaster effigies destroyed. Gaunt’s great-great grandson, Henry VII, had the tomb restored. In 1614 it was described as 'a most stately monument, but when Old St Paul's Cathedral was destroyed in Great Fire of London, John of Gaunt's tomb was 'burnt to ashes’. It is unlikely, therefore, that the corpses of John and Blanche were among those that were dragged from the ruins and propped up in Convocation House Yard for passers-by to gawp at.

If you were surveying the Thames riverfront in London over four hundred years ago, and were standing on the south bank outside the Tate Modern, you would have seen on the opposite side of the river a large palace with turrets and a water gate.

This was Baynard’s Castle, originally one of three fortresses built by William the Conqueror to defend London. The original Baynard’s Castle was a Norman stronghold that stood slightly inland, but this was demolished around 1276 to enable the Black Friars to extend their monastery – the monastery where in 1529 Katherine of Aragon went on her knees before Henry VIII and begged him to spare her the extremity of a divorce court.

In 1338 Baynard’s Castle was described as a ‘tower on the Thames by the place called Chastel Baynard’. After a serious fire in 1428 it was rebuilt on land reclaimed from the river by Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, brother of Henry V. On the death of Duke Humphrey in 1447, it passed to Henry VI who granted it to Richard, Duke of York. In 1461 York’s son, Edward IV, was offered the crown of England in the great hall of Baynard’s Castle; and there, in June 1483, Edward’s brother, Richard, Duke of Gloucester was proclaimed King Richard III. In 1485 Baynard’s Castle passed to Henry VII, who transformed it into an imposing royal residence and granted it to his Queen, Elizabeth of York. By then it was a massive white stone edifice with tall towers, rising majestically from the Thames.

In 1509, Elizabeth’s son, Henry VIII, gave the castle to his bride, Katherine of Aragon. It continued to be an important royal palace until 1551, when Edward VI presented it to William Herbert, Earl of Pembroke. In 1666 the Great Fire of London destroyed much of the building; only one turret survived for another sixty years. The remains of Baynard’s Castle stayed below ground until 1972, when the construction of a new dual carriageway and flyover on the north bank of the Thames prompted a major rescue excavation. When the archaeologists had left the site, it was completely covered with new roads and modern buildings, and the foundations of Baynard’s Castle disappeared from view.

Looking at London’s skyline now, it is hard to imagine how in centuries past the turrets of the royal palace of Baynard’s Castle, rising vertically from the waters of the Thames, would have completely dominated the north side of the riverfront.

Another great mansion, Coldharbour, built in the fourteenth century, stood on the northern foreshore of the Thames. Among its famous residents were Henry IV, Henry V, Sir John de Pulteney - four times mayor of London and builder of Penshurst Place - and Alice Perrers, Edward III's notorious mistress, who added a tower. In 1484 Richard III granted Coldharbour to the royal heralds, but they held it for just a year, until Richard III was killed at Bosworth and Henry VII cancelled the grant of Coldharbour, which he gave to his mother, Margaret Beaufort. Coldharbour also was burned down in 1666 during the Great Fire.

I could add so much more, from the state trials in Guildhall to the wonderful history of St Bartholemew’s – the list would be endless, but contemplating these lost buildings, and the rich heritage that has gone, it is easy to see why the poet William Dunbar wrote, around 1500, ‘London, thou art the flower of cities all!’

Read historical novelist Anne Clinard Barnhill's very kind article, 'Alison Weir and Me', at http://queenanneboleyn.com/2013/10/30/alison-weir-and-me-by-anne-clinard-barnhill/

"THE AMAZING BEST SELLING AUTHOR ALISON WEIR"

(Broadway to Vegas, September 2012)

Those Tudors were an amazing group. Sex, murder, mistresses, intrigue. A dysfunctional family if there ever was one. But, oh, so interesting. Riveting as brought to life by best-selling author Alison Weir, who spoke with Broadway To Vegas about her own interesting life, as well as the antics of those who flow from her prolific pen. Her history books, and latterly historical novels, mostly in the form of biographies about British royalty from the Tudor period have made her a best-selling author.

The Tudor period was dramatic, vivid with strong female personalities. It is also the first one for which there is a rich visual record, with the growth of portraiture, and detailed sources on the private lives of kings and queens.

Weir has sold more than 2.3 million books: with more than a million of those sales coming from the United States. She is also the 5th best selling historian in the United Kingdom. The top four are Antony Beevor, Stephen Ambrose, Simon Schama and Peter Ackroyd.

Weir's fourth novel, A Dangerous Inheritance, is the stand-alone sequel to Innocent Traitor. It tells the story of Lady Katherine Grey, and is a suspenseful tale about one of history's most controversial mysteries, approached from a new angle in an intriguing sub-plot, with a hint of the supernatural. The paperback edition of Alison's latest biography, Mary Boleyn, was published in America on September 4, 2012.

Weir specializes in writing about a century of raw power and rude humor. As to whether any of the relatives of figures in her books have contacted her with their opinions, Weir replied: "Anya Seton's daughter contacted me after I had written an appendix about her mother's novel, Katherine, in my biography of Katherine Swynford. She was happy with my portrayal of her mother and said I'd got it mostly right!"

Some people not only appear to have it all, but make it look so easy. Underneath the success is a lot of talent and tenacity.

Meet the personal side of Alison Weir. Born and bred at Westminster, London, she has also lived in Norfolk, Sussex and Scotland, and now resides in Surrey.

'My parents split up when I was young, and my father died many years ago," Weir told Broadway To Vegas. "He instilled in me a love of classical history when I was a child, and introduced me to the works of Robert Graves and Mary Renault."

Weir has been interested in Tudor history since the age of fourteen, when she read her first adult novel, a rather lurid book called Henry's Golden Queen, about Katherine of Aragon. She was so enthralled by it that she dashed off to read real history books, to find out the truth behind what she had read, and thus her passion for history was born. By the time she was fifteen, she had written a three-volume reference work on the Tudor dynasty, a biography of Anne Boleyn based partly on contemporary sources, and several historical plays. She had also started work on the research that would one day take form as her first published book, Britain's Royal Families.

Alison was educated at the City of London School for Girls and the North Western Polytechnic, training to be a teacher with a major in history. However, she quickly became disillusioned with trendy teaching methods. Before becoming a published author in 1989, she was a civil servant, then a housewife and mother.

It should come as no surprise that super-mom Alison Weir did what a lot of mothers are required to do - rise to the occasion.

From 1991 to 1997, while researching and writing books, she also ran her own school for children with learning difficulties. "My son has special needs and we couldn't find a suitable school for him," she told Broadway To Vegas. "So, I set up my own!"

She's been married to Rankin Weir since 1972, and they have two children, John who was born in 1982 and Kate who came along in 1984. "My husband was a civil servant until 2001; since then, he has worked for me. He is the bedrock of our lives - I couldn't do this without him," she stressed. "My children, indeed my whole family, are all marvelously supportive."

Alison Weir will take part in a book reading and signing of Captive Queen on September 28 to benefit the The Friends of Northampton Castle, a volunteer group established to publicize the castle and provide information about the history of the site and the castle itself. In July 2012, FONC commissioned a 3D reconstruction of the castle which has been published on youtube. Thomas Becket was tried at the castle in 1164.

Being an organized pack rat can be important to a successful author. "I save most things, and yes, I have used a huge amount of my earlier research in my books," she said answering a Broadway To Vegas question. "I'm now rewriting two early novels, and am about to base a book on England's medieval queens on research I did four decades ago."

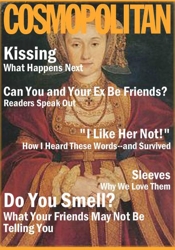

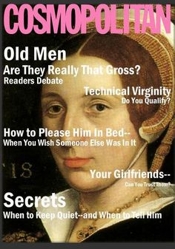

In the 1970s, Weir spent four years researching and writing a non-fiction biography of the six wives of Henry VIII. Her work was deemed too long by publishers, and was consequently rejected. A revised version of this biography would later be published as her second book, The Six Wives of Henry VIII.

In 1981, she wrote a book on Jane Seymour, which was again rejected by publishers, this time because it was too short. Weir became a published author in 1989 with the publication of Britain's Royal Families, a compilation of genealogical information about the British Royal Family. She revised the work eight times over a twenty-two year period, and decided that it might be "of interest to others".

What Weir's writing has done to encourage an interest in history is magnificent. However, she hasn't attempted to get her books turned into movies or a PBS special because, frankly, "Normally, broadcasting companies approach me."

Those who are successful authors of romance novels know there is a formula. What about historical fiction? "It all depends on your publisher, and editors vary widely in their opinions," she answered. "I was given a lot of excellent advice (e.g. show, rather than tell), so I do bear that in mind, but by now it's virtually become second nature."

As to whether she has a favorite character that she'd would like to spin off into a series of books, Weir replied: "Not yet, but I'm thinking about it! A female detective who solves historical mysteries would sing to me!"

Weir's writings have been describing as being in the genre of popular history, which has attracted criticism from academia.

Weir is not apologetic. "History is full of wonderful stories and amazing characters. I feel very privileged to be able to bring them to life in both my non-fiction books and my novels. In both cases, I feel that an author has a responsibility to be as true to the facts as is possible. And in an age in which history is increasingly perceived to be 'dumbed down' in schools, on television and on film, we can all learn from a study of the past. We can discover more about ourselves and our own civilization.

"History belongs to us all, and it can be accessed by us all. And if writing it in a way that is accessible and entertaining, as well as conscientiously researched, can be described as popular, then, yes, I am a popular historian, and am proud and happy to be one."

THE WHITE ROSE OF SCOTLAND

A NOVEL OF LADY KATHERINE GORDON

(Unsubmitted proposal, 2014. This book was also proposed as a biography.)

Perkin Warbeck; Elizabeth MacLennan as Katherine Gordon in the BBC TV series 'The Shadow of the Tower' (1972). No contempory image of Katherine exists.

Lady Katherine Gordon is the daughter of a Scots nobleman, George Gordon, Earl of Huntly. She was born in Aberdeenshire in 1474. Her story begins when she is brought to the court of King James IV at Stirling Castle in November 1495. James has welcomed a controversial young man to his court. Handsome and gallant, the newcomer insists he is Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes in the Tower (whom many believed to have been murdered twelve years earlier) – and therefore Richard IV, the rightful King of England. Wishing to discountenance his enemy, Henry VII of England, James has offered Richard his support and received him with royal honours, and offered him his kinswoman, Katherine, a young lady of extraordinary beauty, to be his bride.

Richard proves an ardent suitor, sending her passionate letters, and she falls in love with him. They marry in Edinburgh the following January, amidst great celebrations. Katherine is now styled the Duchess of York. One day, she dreams, she will be queen of England.

A son, Richard, is born to them nine months later. Meanwhile, plans have been laid for Katherine's new husband to invade England. While Katherine lies abed recovering from her confinement, James and Richard ride into Northumberland, where Richard issues a proclamation as king of England. But no Englishmen rally to his banner. When the Scots start raiding Northumberland and engaging in border warfare, Richard excites ridicule by entreating James to spare those whom he calls his subjects. Richard is so disgusted by the mayhem that he returns to Scotland after three days, leaving James with no option but to follow.

By July 1497 Henry VII has begun peace negotiations with James, which makes it impossible for Richard to stay in Scotland. Leaving many debts behind, he and Katherine embark with their two children from Ayr in a Breton merchant vessel. The plan is to land in England and seize the English crown, but Richard has no weapons or soldiers.

First they visit Cork, remaining in Ireland more than a month. But Richard fails to rally any support there. Instead the citizens of Waterford fit out vessels at their own cost, and nearly capture him at sea during his crossing to Cornwall. When Richard and Katherine land at Whitesand Bay in Cornwall, he proclaims himself King Richard IV of England, and installs Katherine within the safety of the castle on St Michael's Mount. At Bodmin, he raises three thousand men, with more joining him on his march eastward. Katherine waits in trepidation to hear news of him. Her youngest child has been ailing, and she fears for her life. Then news comes that Richard has been forced to withdraw to Taunton after failing to take Exeter. That same day, her child dies, and she is plunged into mourning.

Then news comes that the King’s army is on the march. Fearful for her son’s safety she arranges for him secretly to be taken to Wales and hidden in a humble farmstead. Soon afterwards she hears that, abandoned by his followers, Richard has surrendered himself to the King's mercy.

Soon the royal soldiers come for Katherine. They tell her that her husband, having been promised his life, has made a full confession of his imposture. He is really Perkin Warbeck, the son of the Controller of Tournai, and he had been persuaded by the Irish to impersonate Richard of York. Katherine is now the King’s prisoner and is to be brought to him at Taunton. Her fears are somewhat allayed when she is provided with mourning attire for her child.

As she rides to Taunton, she wonders if Richard has merely repeated what he was told to say. With his wife – and, he believes, his child - in Henry’s custody, he has little choice. Not knowing what to think, she is in turmoil – and terrified in case Richard (the name she will always call him) will reveal that he has a son, forcing her to divulge the child’s whereabouts.

When Katherine comes into Henry’s presence, he is struck by her beauty and is more than kind to her. Deferring to her rank, he pays her much attention; it seems he feels sorry for her for having married an imposter. He summons Richard and makes him repeat his confession in her presence. Now she is even less sure what to believe.

Henry sends Katherine, under escort, to his Queen, the kind and gentle Elizabeth of York, assuring her of his desire to treat her like a sister. Richard is taken under guard to London, an object of ridicule. At first, he is imprisoned in the Tower, but after publicly repeating his confession in London, he is allowed to live at court. He begs Henry to send Katherine home to Scotland, and even James IV tries to gain her freedom, but Henry fears more plotting will ensue; he has also taken a fancy to Katherine.

Richard is given a place in Henry's household. He is under light house arrest, and has his own servants, a horse and a tailor. He is allowed to see Katherine, but not to sleep with her. She warns him not to reveal that they brought a child out of Scotland. Rightly she fears that any son of the pretender would be in danger, and might be shut up in the Tower like the young Earl of Warwick, who is too near in blood to the throne.

Katherine is made very welcome in Elizabeth of York's household, and becomes a favoured lady-in-waiting. She resumes her maiden name of Gordon and is treated with all the deference due to her noble birth. Soon she is known popularly as ‘the White Rose of Scotland’. The King pays her expenses from his own privy purse. He awards her a pension and gives her lavish clothing. She knows what he wants, and is tempted because she has come to like this man who was once her enemy.

After a year, Richard grows tired of his silken chains and escapes from the court to Sheen Abbey, but the prior informs the King that he is there. This time, Richard is imprisoned in the Tower for good, in a dark cell.

Henry has betrothed his heir, Prince Arthur, to Katherine of Aragon. Her parents, the Spanish sovereigns, will not let her come to England while the Earl of Warwick lives. Henry decides to kill two birds with one stone. An agent provocateur is planted in the Tower, and Richard and Warwick are drawn into a plot. In November 1499 Katherine, disguised, is watching in the crowd when Richard is executed.

After his death she remains at the English court. The King is still giving her lavish clothing. In 1503 she briefly returns to Scotland in the train of Henry’s daughter Margaret, to attend Margaret’s wedding to James IV. By now, Henry is a widower, and on Katherine’s return they become close, spending so much time together that there is speculation they will marry. But Henry is a sick man. He dies in 1509 and his son, Henry VIII, becomes king.

The new King is fond of Katherine, who was much loved by his mother. He appoints her a lady-in-waiting to his queen, Katharine of Aragon. The following year Katherine obtains letters of denization and becomes an English subject. The King grants her lands in Berkshire, on condition that she will not venture within 100 miles of the Scottish border. It is a strange condition to impose, and Katherine wonders if he has found out about her son. All these years she has suffered heartache on account of the boy, denying herself even a glimpse of him to ensure his safety. King Henry, more ruthless than his father, must never know of young Richard’s existence.

In 1512 Katherine marries James Strangeways, one of the King’s gentleman ushers. The Strangeways were once a Yorkist family. Although it is not a happy marriage, it brings Katherine the manor of Fyfield, Berkshire, with its rambling timbered house, which she comes to call home. Here she will live when not at court.

Katherine before Henry VII; Fyfield, Berkshire

In 1517 James Strangeways dies, leaving his estate to his wife. By then, Katherine has fallen in love with an older man, the kindly Sir Matthew Cradock, a Welsh gentleman who has secretly watched over her son for her. They marry soon after James’s death, and the King gives her leave to dwell with her husband in Wales. Cradock is a knight of some standing, and they lead a comfortable life, dividing their time between Cardiff, Swansea, Abertawe and haunted Candleston Castle, near to which there is said to be a lost village buried in the sand dunes. At last Katherine is able to see and get to know her son.

But Queen Katharine has not forgotten her. When her young daughter, the Princess Mary, is sent with her household to Ludlow Castle on the Welsh border in 1525, the Queen appoints Katherine chief lady of the Princess's privy chamber. Again, Katherine realizes she must be circumspect about her life in Wales. She serves the Princess until Mary is recalled to court in 1527. Henry VIII is divorcing Katharine of Aragon, and the Queen begs Katherine to stay with her daughter to support her during this difficult time. Reluctantly, Katherine returns to court, and Matthew takes a house in London. Neither of them are happy to see Anne Boleyn queening it over the court, or to see Mary so unhappy.

In 1530 Matthew’s health breaks down. Katherine is now fifty-six. Her son is a grown man, and she longs to see him again. The Queen gives her permission to go home, and the couple return to Wales. In July 1531 Matthew dies.

Matthew Cradock's bomb-damaged tomb in St Mary's Church, Swansea, now lost; Katherine Gordon's tomb in St Nicholas's Church, Fyfield.

Katherine retires to Fyfield, where she spends the last six years of her life; still beautiful, she becomes a familiar sight, riding her horse around the parish. In 1536 she marries for the fourth time, to a local man, Christopher Ashton, another royal gentleman usher. Nineteen years her junior, he is a widower, and Katherine becomes stepmother to his two young children. She dies at Fyfield in October 1537, much loved by her husband and all who know her.

What had happened to her son? That is one of the central themes of the book. There are hints that the real Katherine Gordon had a son by Perkin Warbeck, and that this Richard Perkins was sent to a family in Wales for safety. It is possible that Katherine spent her whole life concealing his existence, while retaining the affection and respect of the Tudor monarchs. Another theme in the book is how Katherine came to regard Perkin Warbeck, the only one of her husbands not to be mentioned in her will. Did she truly believe he was Richard of York? Or did she feel betrayed by his imposture? The third theme is the nature of her relationship with Henry VII. How close were they?

Katherine Gordon’s is an extraordinary story spanning two rich periods of history, two courts and all four corners of the British Isles. It is a tale of love, ambition, tragedy and intrigue – and of a beautiful and remarkable woman.

BRITAIN'S LOST QUEENS

by Alison Weir, 2012

In the wake of the announcement that the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge are expecting their first child, and the new legislation to give their daughters equal precedence with their sons in the order of succession, it is interesting to speculate which princesses would have reigned in England had this law been enacted in past centuries, when several monarchs left daughters who were older than the sons who succeeded them.

Until Elizabeth I proved that a woman could rule successfully, the concept of a a female monarch was unacceptable to the male-dominated society of medieval and Tudor England. It was a world in which women were regarded as inferior to men physically, intellectually and morally, and were legally infants. It was seen as against the laws of God and Nature for a woman to wield dominion over men: such a thing was an affront to the perceived order of the world.

Setting aside such prejudices, and the necessity in earlier times for a ruler to be an active war leader, who were the queens England - and later Great Britain - never had?

In 1135, the Empress Matilda, daughter of Henry I, was actually her father’s thrice acknowledged heir, but on his death the barons opted for her cousin Stephen instead. Matilda launched a civil war in defence of her rights, but her bid for power failed in the face of her perceived arrogance, and the Londoners wasted no time in kicking her out.

In 1307, instead of the weak and vicious Edward II, there would have been Margaret I, former Duchess of Brabant, the eldest surviving daughter of Edward I. She is a shadowy figure about whom there is little to say, but her accession would have seen closer links with the Low Countries and put a strong foreign dynasty on the English throne.

Had the law been passed later – which we will suppose in each future case - the next Queen would have been Elizabeth I – not the Gloriana of legend, but Elizabeth of York, who was the rightful Queen of England after the probable murder of her brothers, the Princes in the Tower, in 1483. She and her siblings had by then been declared legitimate, but on dubious grounds. Their bastardy was ratified in law in 1484, but reversed by Parliament in 1485, by which time Henry VII, Elizabeth’s future husband, was king. She had the better title, and since her bastardy had been nullified, her rights should have taken precedence over his. But because she was a woman, no one even considered supporting her claim, and Elizabeth herself certainly did not press it. She was seen chiefly as the heiress of the House of York, through whom the right of succession could be transmitted by marriage.

Under today’s legislation, we would have had no Henry VIII – at least not until 1541 - and England’s history would have been very different. Henry VII would have been succeeded in 1509 by his eldest surviving child, Margaret Tudor, Queen of Scots, as Margaret II – ‘Henry VIII in a dress’, as Sarah Gristwood has described her - and that would have united the crowns of England and Scotland almost a century earlier than in reality, and the Tudor dynasty would have lasted just twenty-four years. Had Margaret died childless in 1541, Henry VIII would have succeeded at the age of fifty, and Scotland would have come under Tudor rule.

If the law had been passed by Henry VIII – although he would be spinning in his grave at the thought – his eldest daughter, Mary I, would have succeeded him in 1547. She would then have been thirty-one, and more likely to have borne children than she actually was when she came to the throne in 1558 – and England may well have remained a Catholic country.

On her death, assuming she was childless after all, the succession would then have followed its historical course, passing to her half-sister, Elizabeth II (I) – we will use these regnal numbers on the assumption that the issue, or lack of it, of these queens made little impact on the historical succession; if it had, the course of history naturally would have been very different.

In 1625, Elizabeth’s successor, James I, would have left the crown to his eldest surviving child, Elizabeth III, titular Queen of Bohemia. That would have established the prolific Palatine dynasty on the throne, and probably averted the English Civil War, although it might have dragged Britain into the gruelling Thirty Years War.

Had the legislation been passed later, Mary II and Anne would have reigned anyway, but in 1760, instead of passing to George III, the crown would have gone to his sister, Queen Augusta, Duchess of Brunswick, which would have brought another German dynasty to the throne. There might have been no American War of Independence and certainly no Regency.

If the new law had been passed in the nineteenth century, Queen Victoria would still have succeeded in 1837, but on her death in 1901, instead of Edward VII, there would have been – for a few months - Victoria II, the former Princess Royal and Empress Frederick of Prussia. When she died of cancer later that year, the German Kaiser Wilhelm II would have become King of Great Britain, and there would have been no Great War, and probably no Second World War, because the Kaiser would never have been forced to abdicate. His dynasty, the Hohenzollerns, would have continued to rule Britain and Germany, and the House of Windsor would never have existed. Today, the Kaiser’s descendant, Prince Georg Friedrich of Prussia, current head of the House of Hohenzollern, would reign here as George VII.

Much of this is purely speculative, of course, yet it is fascinating to wonder what would have happened if each of these ladies had succeeded to the throne.

REEL LIVES

from Spectrum, The Scotsman's Sunday magazine, April 2003

As someone who is passionate about the past, I am an avid viewer of historical films, and enjoy watching them on video again and again. As an historian, however, I am probably more aware than most people of the factual errors that are - sometimes deliberately - made by film-makers, whose brief is to reconcile historical accuracy with dramatic licence and produce a visual interpretation that is commercially viable.

As a writer who is constantly researching from contemporary sources, establishing facts and striving for historical accuracy, I am sometimes horrified at the liberties that are taken by film-makers. History, as they say, is stranger than fiction, and I see no need to embellish or alter it in the essentials, especially where the facts are well known. There is plenty of scope for invention where there are gaps in our historical knowledge or opportunities to interpret private relationships. Furthermore, I feel it is perfectly legitimate, in the interests of creating a good drama, to telescope events or create symbolic scenes.

Being something of an old reactionary, however, I tend to feel that historical films were sometimes done better in the past than they are now. There is no doubt that history is being dumbed down by television and film-makers, whose attitude to their audiences seemingly borders at times on the patronising or contemptuous. Only the other day, a BBC researcher spoke to me of using, in a historical programme, "language that a BBC1 audience can understand”. This is surely vastly underestimates viewers’ intelligence.

Any historical drama will automatically attract a well-educated audience with some knowledge of a subject in which they already have an interest. I know this from the attendances and questions at my talks on popular figures such as Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and Mary, Queen of Scots. And having talked to numerous readers, I know that they enjoy historical dramas. But there is little doubt that they are being sold short.

Many of the historical personages I have written about have been the subjects of films or TV drama series. Eleanor of Aquitaine

was one of the chief protagonists in the 1968 film, ‘The Lion in Winter’, starring Katharine Hepburn as Eleanor and Peter O'Toole as

Henry II, with a strong supporting cast. From 1173 to 1189, Henry kept Eleanor a prisoner after she rebelled against him with their sons, but in the 1180s she was allowed to join the court at Christmas and other festivals. In his intelligent screenplay, James Goldman imagines the interplay between the royal couple and their children during one Christmas at Chinon.

Katharine Hepburn's portrayal of Eleanor is masterful, as is Peter 0’Toole’s as Henry. This is essentially a film about relationships and power politics, with sharp, witty dialogue. I was saddened when a TV scriptwriter told me recently that "they wouldn't make it now".

O'Toole also played Henry II in an earlier film, ‘Becket’(1964), based on Jean Anouilh’s incisive stage comedy, opposite Richard Burton in the title role. Again, the script is clever and lively, with relationships and the conflicting issues of loyalty, morality and political expediency explored in depth in the compelling interaction between the main characters. Eleanor of Aquitaine makes a peripheral appearance in this film, but no attempt has been made to portray her as anything other than a shrewish queen who has no attraction for her husband. Glaringly, her costume is of the 15th rather than the 12th century. Nevertheless, these minor details should not detract from an otherwise excellent film.

A third portrayal of Eleanor was by Jane Lapotaire in the BBC TV series ‘The Devil’s Crown’ (1978), which starred Brian Cox as Henry II. The series depicted the reigns and relationships of the first three Plantagenets, and the tie-in book was written by an eminent historian, Richard Barber. A worthy attempt was made at historical accuracy; the script and acting were excellent, but some critics disliked the stagey sets and painted backdrops. Today, this splendid series is largely forgotten.

Apart from the BBC"s cycle of Shakespeare's plays, there have been few attempts to depict the Wars of the Roses on film, but Richard III was the subject of the definitive 1955 film based on the Bard's play. This film starred, and was adapted and directed by, Laurence Olivier, whose vivid portrayal of the King owed not so much to history as to a study in villainy. ‘Richard III’ was re-made in 1995 with lan McKellen in the title role; this time, the setting was not 15th century England, but an imaginary Fascist Britain of the 1930s, which worked very well, with the King being transformed into a dictator.

In my book The Princes in the Tower, I explored the histories of the pretenders who so troubled Henry VII by their claims to be scions of the House of York. An undeservedly forgotten BBC TV Series, ‘The Shadow of the Tower’ (1972), recounted their stories among other events of Henry VII"s reign, and starred the mesmeric James Maxwell as Henry. The series was soundly researched and well-scripted, with stunning costumes and convincing sets. It is a shame that it has not surfaced on video. [Note: this series is now available on DVD.]

Henry VIII and his wives have been the subjects of two of my books, and have often been portrayed on screen. The first major film about Henry VIII was Alexander Korda's ‘The Private Life of Henry VIII’ (1933), starring Charles Laughton. Laughton personified the popular perception of Henry as a bluff, gluttonous womaniser. The film begins with Anne Boleyn’s execution and ends with a comical portrayal of the ailing Henry suffering the nagging of a brisk Katherine Parr; in between, an inordinate amount of time is devoted to the love affair between an astonishingly mature-looking Katherine Howard and Thomas Culpeper.

The film was enormously influential, but it was Hollywood's interpretation of "Merrie England" and could be called the celluloid equivalent of a narrative painting of the romantic era, reflecting the preoccupations and fashions of its own time rather than the genuine realities of Tudor history. Laughton’s portrayal of the King is a mere caricature, but has been so powerful that it still influences popular perceptions of Henry today.

In 1953, in the Walt Disney film, ‘The Sword and the Rose’, Henry was again presented as a bluff, larger-than-life egotist, this time by James Robertson Justice. The film recounted – with hopeless inaccuracy - the love affair between Henry’s sister Mary (Glynis Johns) and Charles Brandon, and is best forgotten.

A much more serious portrayal of Henry VIII featured in Fred Zinnemann’s outstanding film about Sir Thomas More, the Oscar-winning ‘A Man for All Seasons’ (1966), which was based on Robert Bolt's very challenging stage play. Robert Shaw played a younger, slimmer Henry (early film-makers never took into account the fact that the King only became overweight in the last decade of his life), preoccupied with his need for a son and his conviction that his marriage to Katherine of Aragon was invalid. He is no caricature, but an attractive man whose every whim has hitherto been gratified, and who cannot now deal with any opposition to his views - a man whose finer self is at war with his baser needs.

Katherine of Aragon does not appear in the film, but Vanessa Redgrave makes a fleeting, unspeaking appearance as an incredibly authentic- looking and flirtatious Anne Boleyn.

Robert Shaw's role was disappointingly reprised in a 1988 television version of the film, starring Charlton Heston as Sir Thomas More. Heston himself played an ageing, and fairly convincing, Henry VIII in a cameo role in ‘The Prince and the Pauper’ (1977), based on Mark Twain"s novel and starring Mark Lester as a much-too-grown-up Edward VI.

The romantic view of Henry VIII was still evident in Charles Jarrott’s lavish film ‘Anne of the Thousand Days’ (1969), featuring Richard Burton as the King. Although visually stunning and shot in authentic locations (though often with dubious costumes), the film presented Hollywood"s distorted view of Tudor history, with (for example) Henry visiting Anne Boleyn when she was a prisoner in the Tower (in reality, the King never had any personal contact with those arrested for treason).

Disappointingly, Burton's acting was formulaic, as if he were playing a parody of his role and wished to distance himself from it. Genvieve Bujold had greater conviction as Anne Boleyn, but, given the fine supporting cast, this film could have been far better, given its good script, which derived from the stage play.

For me, the greatest and most accurate portrayal of Henry VIII was that by Keith Michell in the BBC TV series ‘The Six Wives of Henry VIII’ (six 90 minute plays, 1970), an outstanding production that was based on original source material and sound research, and - allowing for an acceptable degree of dramatic licence - achieved a high standard of authenticity that has never been surpassed.

An excellent spin-off film, ‘Henry VIII and his Six Wives’, followed in 1972, and again starred Keith Michell, but with different actresses playing the wives. Again, the production was remarkable for its historical accuracy. Keith Michell played Henry VIII one more time, in the BBC drama serial ‘The Prince and the Pauper’ (1997).

Later this year, there is to be a new Granada Drama TV series about Henry VIII, starring Ray Winstone and Helena Bonham-Carter. Henry and Anne and Mary Boleyn also feature in the television dramatisation of Philippa Gregory's novel, The Other Boleyn Girl.

Helena Bonham-Carter is no stranger to playing Tudor queens. In 1985 she starred in the title role in Trevor Nunn's film, Lady Jane, about the ill-fated nine-day Queen, Lady Jane Grey. Helena Bonham-Carter"s performance convinces, but the romantic portrayal of Jane’s relationship with her husband, Lord Guildford Dudley (Cary Elwes), is a travesty of historical truth. Otherwise, the film is sumptuously produced and well-acted.

Elizabeth I has been the subject of many films. Bette Davis’s was perhaps the most famous screen portrayal; she starred in ‘The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex’ (1939) with Errol Flynn, and ‘The Virgin Queen’ (1955). Both these films received the usual glamorous, anachronistic Hollywood treatment of English history, and Davis's studied and overplayed Elizabeth is merely a two-dimensional caricature of the historical figure.

I have to confess to not having seen Flora Robson's Elizabeth in ‘Fire Over England’ (1937), although I am aware that the film was dismissed as "swashbuckling nonsense" by one critic. The same could be said of ‘Young Bess’ (1953), starring Jean Simmons, who bore no resemblance at all to the youthful Elizabeth she portrayed.

Again, it was the BBC that produced the definitive Elizabeth, with Glenda Jackson"s brilliant and inspired performance in the 1971 TV series, ‘Elizabeth R.’ In my opinion, this has never been bettered. Like ‘The Six Wives of Henry VIII’, it was based on original source material and boosted by an excellent script, superb acting and authentic costumes.

The same could not be said for the film ‘Elizabeth’ (1998), starring Cate Blanchett. It contained so many factual errors that I could not list them all here. To give just a few examples: the Duke of Anjou who came courting the Queen was portrayed as a transvestite, when in fact it was his brother, Henry III of France, who dressed as a woman; the Duke of Norfolk was shown as a menacing, deadly threat to the throne, when in fact he was a dilatory and inept plotter; Durham Cathedral, with its dreadfully anachronistic Romanesque architecture, was used as Whitehall Palace; the plot against Elizabeth was a confused mish-mash of several conspiracies, and hardly any mention was made of their focal point, Mary, Queen of Scots. As one critic said, this was a film strictly for the MTV generation. Yet ‘Elizabeth’ was showered with awards – a Bafta and a Golden Globe for Blanchette’s central performance, and Oscar nominations for Best Picture, Best Actress and Costume Design.

Mary, Queen of Scots, the subject of my latest book, has yet to be realistically played on film. ‘Mary of Scotland’ (1936), starring Katharine Hepburn, is the usual Hollywood pastiche, with plenty of bagpipes whenever the Earl of Bothwell appears. ‘Mary, Queen of Scots’ (1971), though, features a sympathetic performance by Vanessa Redgrave as Mary, with Glenda Jackson reprising her role as Elizabeth I. The film shows the two Queens meeting - which never happened in real life - and deftly manages to avoid confronting any of the controversial issues surrounding Mary.

The book I am researching now is entitled Isabella, the She-Wolf of France, and is about the Princess who appears in the film "Braveheart", starring Mel Gibson and Sophie Marceau. This film has stunning, but highly inaccurate, battle scenes, and a poignant imaginary love story between the Scottish patriot, William Wallace, and Isabella, the wife of the future Edward II of England. On celluloid, such a love was inevitably doomed, for Isabella, although beautiful and spirited, was trapped in a loveless marriage to a homosexual, while Wallace would end up suffering the barbaric death meted out to traitors. The film ends, however, with a poetically just hint that the child Isabella was carrying, the future Edward III, was in fact fathered by Wallace.

It’s all very stirring stuff, but nothing could be further from the truth; in fact, on the basis of the film"s claims, this would have been the longest pregnancy in history. Wallace was executed in 1305, and Isabella did not come to England and marry Edward II until 1308; their eldest son, the future Edward III, was not born until 1312. So Isabella had nothing to do with Wallace. Thus are historical facts wantonly sacrificed in the interests of commercialism.

Personally, I would like to see a return to the time when film makers had more respect for history and for the intelligence of their audiences. History is now more popular than ever, but we need to distance ourselves from the modern received wisdom that it is better to have inaccurate history than no history at all. After all, history is fascinating and astonishing in its own right: you could not make it up, nor should you have to. It is unjustified arrogance and inverted elitism to think otherwise.

THE HOWARDS: THE RISE AND FALL OF A NOBLE FAMILY

by Alison Weir

The four Howard dukes of Norfolk, with Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey (second from right).

Everyone familiar with the history of Tudor England will have heard of the Howards, or the dukes of Norfolk, England's premier Catholic family. Katherine Howard was Henry VIII's fifth wife, while his second, Anne Boleyn, had a Howard mother. John Howard, first Duke of Norfolk, a descendant of Edward I, fell fighting for Richard III at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. His son, Thomas, a soldier and statesman, had to fight his way back to royal favour under Henry VII and Henry VIII, and was not restored to the dukedom until shortly before his death in 1524.

His son, Thomas Howard, the 3rd Duke, was the Norfolk so renowned as Henry VIII's henchman. As Earl Marshal of England, he presided over most of the great events of the reign, including several state trials, and he was at the centre of many court intrigues. A blunt, ambitious and ruthless character, he cared for little but his own and his family's advancement. After the execution of his niece, Katherine Howard, in 1542, he and his family fell from favour. Further intriguing brought Norfolk to the Tower and a sentence of death, which he narrowly escaped because the King died before he could sign the warrant for the execution. Norfolk remained in the Tower during the six years of Edward's reign, but was released by Mary and, at the age of 80, helped her to put down Wyatt's rebellion.

Norfolk married twice, firstly to Anne of York, daughter of Edward IV; his second wife was Anne Stafford, who complained he ill-treated and abused her, preferring the company of his mistress, Elizabeth Holland.

Norfolk's son and heir was Henry Howard, Earl of Surrey, the renowned poet and courtier, who was brought up in the company of Henry VIII's bastard son, the Duke of Richmond. Suspected of treason, Surrey was sent to the Tower with his father in 1546, and was the last man to be beheaded in Henry VIII's reign.

His son, Thomas Howard, was later restored to the dukedom of Norfolk and married three times. During the reign of Elizabeth I, he foolishly intrigued to marry the captive Mary, Queen of Scots, with a view to setting Mary on the English throne with himself as her consort. The plot was discovered and Norfolk went to the block in 1572.

Thereafter, the fortunes of the Howard family diminished, as they identified themselves with the Catholic cause, which was tantamount to treason at that time. Norfolk's son, Philip, spent most of his life in the Tower for his faith, died there, and was later made a saint. Only towards the end of Queen Elizabeth's reign did the Howard fortunes begin to revive, but the family never regained its former prominence.

Writtem for London History magazine, 2002 (this magazine was never published):

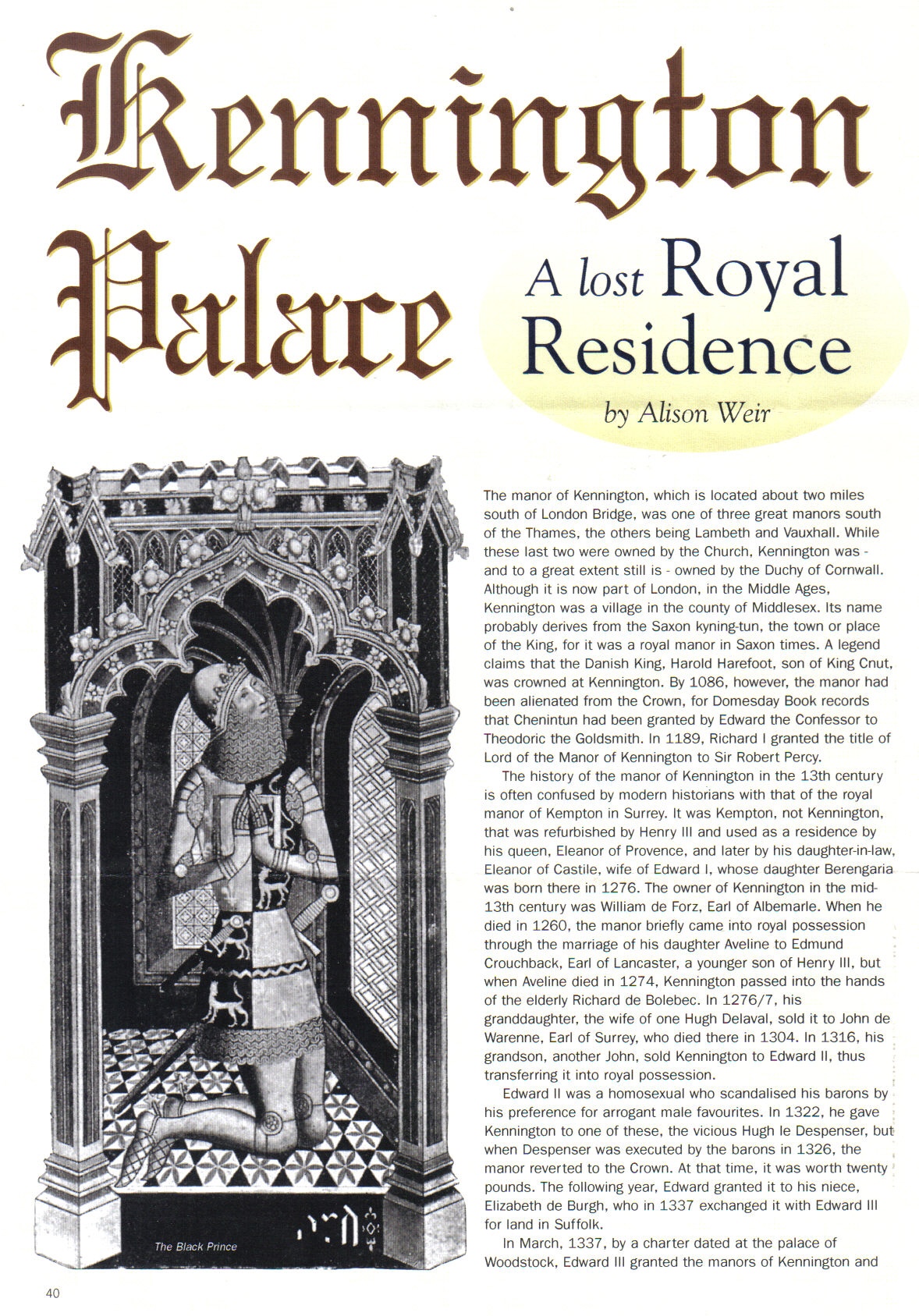

The manor of Kennington, which is located about two miles south of London Bridge, was one of three great manors south of the Thames, the others being Lambeth and Vauxhall. While these last two were owned by the Church, Kennington was - and to a great extent still is - owned by the Duchy of Cornwall. Although it is now part of London, in the Middle Ages Kennington was a village in the county of Middlesex. Its name probably derives from the Saxon kyning-tun, the town or place of the King, for it was a royal manor in Saxon times. A legend claims that the Danish King, Harold Harefoot, son of King Cnut, was crowned at Kennington. By 1086, however, the manor had been alienated from the Crown, for Domesday Book records that 'Chenintun' had been granted by Edward the Confessor to Theodoric the Goldsmith. In 1189 Richard I granted the title of Lord of the Manor of Kennington to Sir Robert Percy.

The history of the manor of Kennington in the 13th century is often confused by modern historians with that of the royal manor of Kempton in Surrey. It was Kempton, not Kennington, that was refurbished by Henry III and used as a residence by his queen, Eleanor of Provence, and later by his daughter-in-law, Eleanor of Castile, wife of Edward I, whose daughter Berengaria was born there in 1276. The owner of Kennington in the mid-13th century was William de Forz, Earl of Albemarle. When he died in 1260, the manor briefly came into royal possession through the marriage of his daughter Aveline to Edmund Crouchback, Earl of Lancaster, a younger son of Henry III, but when Aveline died in 1274, Kennington passed into the hands of the elderly Richard de Bolebec. In 1276/7 his granddaughter, the wife of one Hugh Delaval, sold it to John de Warenne, Earl of Surrey, who died there in 1304. In 1316 his grandson, another John, sold Kennington to Edward II, thus transferring it into royal possession. Edward II scandalised his barons by his preference for arrogant male favourites. In 1322 he gave Kennington to one of them, the vicious Hugh le Despenser, but when Despenser was executed on the orders of Edward's disaffected Queen, Isabella of France, in 1326, the manor reverted to the Crown. At that time it was worth twenty pounds. The following year, Edward granted it to his niece, Elizabeth de Burgh, who in 1337 exchanged it with Edward III for land in Suffolk.

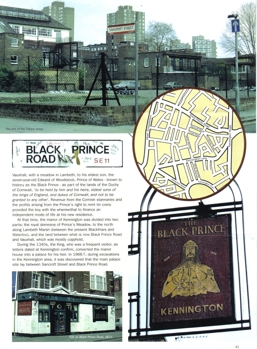

In March, 1337, by a charter dated at the palace of Woodstock, Edward III granted the manors of Kennington and Vauxhall, with a meadow in Lambeth, to his eldest son, the seven-year-old Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales - known to history as the Black Prince - as part of the lands of the Duchy of Cornwall, 'to be held by him and his heirs, eldest sons of the kings of England, and dukes of Cornwall, and not to be granted to any other'. Revenue from the Cornish stannaries and the profits arising from the Prince's right to mint tin coins provided the boy with the wherewithal to finance an independent mode of life at his new residence.

At that time, the manor of Kennington was divided into two parts: the royal demesne of Prince's Meadow, to the north along Lambeth Marsh (between the present Blackfriars and Waterloo), and the land between what is now Black Prince Road and Vauxhall, which was mostly copyhold.

During the 1340s, the King, who was a frequent visitor (as letters dated at Kennington confirm), converted the manor house into a palace for his heir. In 1966-7, during excavations in the Kennington area, it was discovered that the main palace site lay between Bancroft Street and Black Prince Road. The palace comprised a number of separate buildings in series, the great hall being at the centre. The excavation uncovered its undercroft, with evidence that both hall and undercroft had vaulted ceilings supported by two rows of pillars; the height of the undercroft has been calculated at eight and a half feet. Adjoining the hall to the north-west was the smaller Prince's Chamber, with the privy or 'high chamber' above, next to which was a 'little chapel'. The Queen's chamber stood apart, but in line with the other buildings and surrounded by the privy garden. To the south of the great hall were buildings housing the service complex, including the kitchen, the larder and the saucery. At the south-east end of the site, built at right angles to the hall, was a long stable block.

The palace gardens, which in 1390 were described as being rich with vines, extended as far as the present East Stand of the Oval Cricket Ground, which itself is still part of the Duchy of Cornwall Estate. A little way to the north lay Lambeth Palace, the London residence of the Archbishops of Canterbury. The vine garden survived at least until 1461, and was perhaps located in the Prince's Meadow; in the early 14th century Hugh le Despenser had sent wine made at Kennington to the London markets.

The Black Prince lodged at Kennington whenever his presence was required in London, and made many improvements to the palace. In the Register of the Black Prince there exists an order to his receiver general 'to pay the Prince's clerk, Sir Richard de Rotheley, whom the Prince has appointed controller of his masonry works at his manor of Kennington, the fourpence halfpenny a day granted him until the works be completed, in addition to the sevenpence halfpenny granted him for his wages, provided that he find a clerk to enrol and enter the particulars of the works'. These works included masonry, carpentry and 'ironwork ... for the hall and the Prince's chambers there'.

Evidently the work was not carried out to the Prince's satisfaction, for throughout the 1350s there were further extensions, improvements and repairs. These included the building of a new hall, designed by the renowned master mason, Henry Yevele. This hall, which was five years in the building, measured 90' by 50'; it was faced with Reigate stone, had three fireplaces and a tiled roof, and was adorned with statues. The floor was probably laid with glazed tiles decorated with the Prince's arms. When the Black Prince was in residence, the walls were probably hung with the sets of tapestries that he is known to have owned. The Prince also ordered the storehouses in the vaults of the hall to be searched, cleared and 'filled with earth or turf and rubble, in such a way as shall best tend to the preservation of the vaults'.

In 1362, the Black Prince spent the summer at Kennington with his new bride, Joan of Kent. That same year, he granted the manor of Vauxhall to the Prior and Convent of Christ Church, Canterbury, and from that time onwards the two manors remained under separate ownership.

Although he spent long periods at Kennington during his last illness, it was at Westminster Palace that the Black Prince died in 1376, having been too weak to make one final journey to Kennington. His widow, Joan of Kent, and their surviving son, the future Richard II, were staying at the palace when the Prince passed away, and continued to reside there until Richard's accession in June 1377. Richard spent much of his childhood there. By the time he was ten years old, his grandfather Edward III was in his dotage, and much of the burden of government fell on the King's eldest surviving son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. Gaunt was unpopular with the Londoners, who unjustly held him responsible for heavy taxation, and on 1 February, 1377 they marched in a torchlit procession to Kennington to protest about this and secure the support of the Princess of Wales and her young son. Three weeks later, the London mob attacked Gaunt's palace of the Savoy, and he was forced to take a barge along the Thames and flee for his life to Kennington. The pursuing Londoners, who were reluctant to attack the home of the young Prince and his mother, were made to disperse by the formidable Joan of Kent.

In June 1377, when it was known that Edward III was dying and that young Richard would soon be king, the Londoners sent a deputation to the Prince and his mother at Kennington, asking for Richard to look with favour upon the City of London and mediate in the quarrel between the citizens and Gaunt. This led to a reconciliation soon after Richard's accession. Later in June in the great hall of 'his manor of Kennington', in the presence of the King of Castile, the new King entrusted the Great Seal of England to the Lord Chancellor. On 31 May 1388 Richard II entertained the Lords and Commons of Parliament at Kennington, and in 1396 his seven-year-old bride, Isabella of Valois, stayed there before making her state entry into London; John Chamberlain, Clerk of the King's Works, had spent £36 on refurbishing the palace prior to her arrival. Chamberlain's predecessor in office had been the celebrated writer, Geoffrey Chaucer, author of the 'Canterbury Tales', who had been appointed Clerk of the Works in 1389.

During the fifteenth century Kennington Palace remained a favoured royal lodging and was kept in good repair, as numerous entries in the Patent Rolls testify. These same accounts show that when the court was in residence it enjoyed a lavish lifestyle.

In the reign of Henry IV, the notorious Lollard, Sir John Oldcastle, was summoned before the King and his Council at Kennington to defend his heretical beliefs; he denied he had ever read more than two pages of the controversial writings of John Wycliffe, but was later burned for heresy. Henry IV's son and heir, the riotous Henry of Monmouth, afterwards Henry V, stayed at Kennington early in 1400 and again in February 1402. At his accession in 1413, the lords rendered homage to him at Kennington, and on the same day the poet Thomas Hoccleve came there to present to Henry his poem on the ideal of kingship.

In 1423 the infant Henry VI stayed at Kennington on the way to the state opening of Parliament in London. The young King sometimes lodged in the palace during his childhood. In 1435 he attended his first Council there, and three years later we hear of him resorting to a secret chamber in the palace. Later in the 15th century, Cecily Neville, Duchess of York, the widowed mother of Edward IV and Richard III, occasionally stayed at Kennington during the years before her death in 1495.

The last royal personage to lodge at Kennington Palace was Katherine of Aragon, the future wife of Henry VIII, who stayed in November 1501, just prior to her marriage to her first husband, Arthur Tudor, Prince of Wales. By then, the palace was outdated and decaying. In 1516 the manor was leased to Sir John Pulteney for 21 years, but the palace itself was demolished by Henry VIII in 1531, its masonry being used for the building of Whitehall Palace across the river. Sixteen loads of oaken timber and planks of elm were transported there via Vauxhall. By 1607 only a barn and the empty moat remained; the barn was demolished in 1795. The manor survived, however and was settled by James I on his eldest son, Henry, Prince of Wales. When Henry's younger brother, the future Charles I, became Prince of Wales after Henry's death in 1612, he lived for a time in a house built on the site of the old palace.

Today, sadly, nothing remains to show that one of the great royal residences of medieval England stood on the site; all that is left to betray the ancient royal links with the area are a few street signs that probably mean little to the busy people who pass by on their way.

MONASTICISM IN ENGLAND

My specialist subject at A-Level was ‘Twelfth-Century Monasticism in the West’. This is a talk written for one of English Heritage’s Tours Through Times, on which I was guest historian.

In our modern, secular world, we are often unaware of how large a part religion once plates in people’s lives. Hundreds of years ago, England was populated with numerous abbeys and priories in which countless people lived lives of prayer, often secluded from the world.

The earliest monastic Order was that of the Benedictines, founded by St Benedict in the early 6th century. By the time of his death in AD 543, he had founded fourteen houses of men and women whose lives were devoted to the service of God. St Benedict wrote the earliest monastic rule, declaring: "In living our life, the path of God's commandments is run with unspeakable loving sweetness: so that, never leaving His school, but persevering in the monastery until death in his teaching, we share by our patience the sufferings of Christ, and so merit to be partakers of His kingdom."

The aim of the rule was for each individual to attain a state of sanctity that was compatible with living in a community and the performance of the divine offices in choir.

Throughout the Dark Ages and the early medieval period, the Order spread, and it became influential in the fields of art, literature and education. The Benedictines were first introduced into England bv St Augustine in the 6th century. By the time of the Dissolution of the Monasteries in the 1530s, there were about 300 Benedictine houses in England, including all the cathedral priories and most of the richest abbeys. The universities of Oxford and Cambridge owe their origins to the monastic foundations of the Benedictines.

Benedictine monks and nuns were required to take vows of chastity, poverty and obedience. Their lives revolved around the ‘opus manus’ (the work of the hands) and the ‘opus Dei’, the work of God (prayers and intercessions). The daily lives of the religious were punctuated by the canonical hours, the services that were held in the conventual church: Prime at 6 am, Terce at 9 am, Sext at noon, None at mid-afternoon. Vespers around 4 pm, Compline at 7 pm, and Matins and Lauds at midnight or daybreak.

Breakfast would be at 6.30am, followed by work or reading. There would be a meeting of the community in the chapter house in the morning, followed by High Mass, then dinner. In the early afternoon, the monks had rest and recreation, followed by work, and supper at 6.30pm. They would retire to bed after Compline.

They slept in their habits in communal dormitories divided into cubicles, each with a writing desk. Bedding consisted of a mat or straw pallet, a woollen covering and a pillow. There was usually a stairway from the dormitory to the church to enable the monks easy access for the night hours.

Most religious houses were built to a similar plan. The principal building was the church, as large and splendid as the community could afford. It was built in a cruciform shape. The domestic buildings were normally erected around a cloister, a galleried quadrangle where the monks could take exercise or work in fine weather. In the centre of the cloister was a square, grassy garth, which served as a burial ground for the community. The chapter house was usually adjacent to the church, while the infirmary and guest house were usually located a little way away from the main complex. The refectory and kitchens normally adjoined the cloister, and there was usually a warming room, where a fire was kept burning in winter; the monks were allowed spend an hour or so each day there.

Monasteries were usually built near rivers or streams to ensure an adequate supply of fresh water and fish.

The abbey precincts of Benedictine monasteries provided all kinds of social services. Their infirmaries treated the sick; their schools offered education for all classes; their guest houses sheltered travellers; they dispensed charity to the poor, and offered employment to the laity; they were often the refuge of undowered girls from good families.

By the 12th century, however, the Benedictine Order had become lax and was falling into disrepute. This was the great age of monasticism, and it gave birth to other Orders that were founded as a reaction to the Benedictine decline.

In 1068 King William the Conqueror marched from the south with all his levies and ravaged York, slaying many hundreds. The north was devastated, and it would take decades for it to recover – and that was largely thanks to the Cistercians.

This was a religious Order for men and women, founded at Citeaux, near Dijon, in 1098, by Robert of Champagne, a Benedictine abbot; it was noted for the rigidity and uniformity of its rule, which was the strictest interpretation of the rule of St Benedict. The Latin name for Citeaux was Cistercium, hence the name Cistercians. The Order was distinguished by its white habits.

The 12th century was the golden age of the Order, when its fame was closely allied to that of St Bernard of Clairvaux, who founded the Cistercian monastery of Clairvaux and was extremely active in encouraging the foundation of further houses. When he died in 1153, the Order had 338 abbeys throughout Europe.

The architectural achievements of the Cistercians at this time were considerable. Many houses reflected Bernard's preference for simple lines in keeping with the gravity and simplicity of the Order. Cistercian abbeys were therefore markedly similar in appearance.

Rievaulx Abbey in Yorkshire was founded during St Bernard’s lifetime. In 1131 the land on which it was to stand was still a wilderness. That year it was granted by Walter 1'Espec to a band of twelve Cistercian monks, who founded the first Cistercian abbey in England. Thus began an exceptionally prosperous House. The ruins that remain were mostly built in the 12th century.

Between 1147 and 1167, under the third Abbot, St Aelred, there were 140 monks and more than five hundred lay brothers. The Cistercians were responsible for restoring prosperity to the ravaged area, principally through sheep farming.

In 1322 Edward II stayed at Rievaulx, but was caught unprepared, and nearly captured by, the raiding Scots, who sacked the abbey after he had fled to York.

By the fifteenth century, the abbey had become too large, and parts of the chapter house, warming house and dormitory were taken down. By now the Cistercians – like the Benedictines before them – had earned a reputation for laxness and greed. As their riches grew, their austerity of life dwindled.

By 1539, the year Rievaulx was dissolved, there were only twenty-two monks. The abbey was left to decay. There were over a hundred Cistercian houses in England, but after the Reformation, the Cistercians disappeared from northern Europe.

The Carthusians were an order of monks founded by St Bruno in 1084 at Grande Chartreuse near Grenoble, France. The chief characteristics of the Order were separate dwelling houses for each monk and a general assembly in church twice each day and once at night. The monks wore rude habits consisting of a haircloth shirt, a white cassock and a black cloak; they ate a most frugal diet, often consisting of raw vegetables and coarse bread. Each cell was furnished with a straw bed, pillow, coverlet and writing materials. Each brother lived in isolation, and never left his cell except for services, celebrations or the funeral of a fellow monk

The Order invented, and still holds the secret of, the liqueur, Chartreuse.

In England, where the Order was first established in 1180, Carthusian monasteries were often known as Charterhouses. The London Charterhouse was founded in 1371.

In the 1530s a Carthusian prior, John Houghton, and many of his monks opposed Henry VIII"s royal supremacy; for this, they died a terrible death.

Mount Grace Priory is England's finest example of a Carthusian monastery. It was established in 1398 by Thomas Holland, Duke of Surrey (a half-brother of Richard II), for twenty monks who, according to their strict rule, lived in separate cells; it was last monastery established in Yorkshire.

After Richard was deposed in 1399, Holland lost his dukedom, and the monastery had much trouble holding on to its endowments. Holland rebelled against the new King, Henry IV, and was beheaded. He was buried here.

At the Dissolution, the last prior, John Wilson, was granted the Lady Chapel - still in use - and a dwelling house on the steep bank above the priory. In 1654 the owner of the ruins, Thomas Lascelles, converted the buildings to the left of the gate into a private residence, which is still lived in.

The remains at Mount Grace give a vivid picture of a Carthusian House and its rule.

A contemplative Order founded as a reaction against the laxity of many monasteries., its monks lived as hermits within their communities. At Mount Grace each had a house, or cell, measuring 27" square, consisting of a living room, bedroom, study and lobby on the ground floor with a workshop above. Each house opened onto a walled garden, with a lavatory – necessarium – at the bottom of it. There was a hatch in the front wall through which food was passed. The monks ate together only on Saturdays. The cells surrounded a large cloister and the small, plain church. One cell has been restored. The cookhouse, granaries, guest house and stables were built on an outer courtyard.

Throughout the 15th century, monasticism was in decline in England. No new Orders were founded apart from that of the Bridgettines, named after their foundress, St Bridget of Sweden. A house of this Order was founded in 1415 at Syon in Middlesex by Henry V. But it was Henry V who also began closing down monasteries that had ceased to be viable. A century later, under Henry VIII, Cardinal Wolsey was doing the same thing, having obtained the permission of the Pope to dissolve some of the lesser houses.

Then came Henry VIII's break with Rome and the Reformation. The King and his chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, regarded the monasteries as potential hotbeds of resistance and papistry. Henry was eager to get his hands on their wealth, their treasures and their lands. He wanted to be able to offer material rewards to those who had supported him in his religious revolution.

In 1535, under the auspices of Thomas Cromwell, a survey was made of the state of all the religious houses in England; it was known as the ‘Valor Eccleciasticus’. Clearly many monasteries were functioning properly, but there were some in which corruption, laxity and debauchery were rife, and Cromwell capitalised on this. "Manifest sin, vicious, carnal and abominable living is daily used and committed amongst the little and small abbeys," his report read. Consequently, between 1536 and 1540, every monastery and convent in England was dissolved. The monks and nuns were pensioned off; some went to religious houses abroad, others were absorbed back into secular society. A few abbots and priors resisted the King's commissioners, and were hanged for their pains.

The deserted monastic buildings were stripped of their treasures, the lead from their roofs and, in many cases, their stones, which were taken away by local people to build houses. The King's coffers grew ever fuller; he took to wearing on his thumb the great ruby that had adorned the shrine of Thomas Becket at Canterbury.