Books

Isabella, She-Wolf of France, Queen of England/Queen Isabella (2005)

"Alison is a great writer. I think her book on Isabella is brilliant, scholarly and will be the most definitive study ever published. She has done an outstanding job….a truly outstanding contribution to the study of medieval history." (P.C. Doherty, author of Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II)

"Meticulously researched and engagingly written, a highly readable tour de force that brings Queen Isabella vividly to life… an utterly compelling, gripping and believable portrait of a formidable mediaeval queen." (Lisa Jardine, The Washington Post)

"Engrossing, because Isabella`s career was unquenchably dramatic…enthralling" (The Independent)

"This meticulous, no-nonsense biography presents a fascinating story complete with puzzles." (The Independent on Sunday)

"Weir has rehabilitated Isabella, while still leaving her with very human and, indeed, royal faults... Weir has done a masterly job of extracting an indomitable woman from a hostile legend." (The Boston Globe)

"This enthralling biography doesn`t just correct the calumny of centuries, it provides a beautifully nuanced portrait of a fascinating lady and gives a vivid sense of the riotously realpolitik of medieval times." (The Scotsman)

"Wonderfully researched…" (Nottingham Evening Post)

"Weir is a practised biographer of queens…for sheer pace of telling, her book is successful." (The Times Literary Supplement)

"Alison Weir`s dynamic account redresses the balance…a seamless tale full of detail…a fascinating read." (BBC History Magazine)

"Isabella pierces the veil of history with scholarly precision. A wealth of careful and astute research reveals a formidable yet tragic figure…A serious rendering of a sensational life." (The Irish Times)

"Alison Weir has a brilliant handle of character-driven history titles." (The Bookseller, Top Title)

"Sure to reign as the definitive word on Isabella for years to come." (Kirkus Reviews)

"This is history which reads like a novel." (Christopher Hudson, The Daily Mail, Critic`s Choice)

"A much more balanced view of Isabella`s life…Alison Weir succeeds in bringing to life a murky period of history that has been shrouded in myth and legend." (The Literary Review)

"A fascinating rewriting of a controversial life that should supersede all previous accounts…Any reader of English history will want this book."

(Publishers Weekly)

"A fascinating portrait... Informative and entertaining, this vivid biography brings to life an historical figure long condemned to notoriety." (Waterstones Books Quarterly)

"A sizzling read." (Scottish Sunday Herald)

"Dramatic and compulsively readable, this biography paints a realistic and compassionate portrait." (Woman and Home)

In Newgate Street, in the City of London, stand the meagre ruins of Christ Church. In the fourteenth century, on the same site, stood a royal mausoleum set to rival Westminster Abbey. Among the many crowned heads buried there was Isabella of France, Edward II's queen - one of the most notorious femmes fatales in history.

Today popular legends speak of how her angry ghost can be glimpsed among the ruins, clutching the heart of her murdered husband, and even the reputable publications of English Heritage maintain that the Queen's maniacal laughter can be heard on stormy nights at Castle Rising in Norfolk. Such stories paint a picture of a tragic, tormented, cruel and evil woman. In literature and poetry, she has fared no better with Christopher Marlowe calling her 'that unnatural Queen, false Isabel'; Thomas Gray appropriating Shakespeare's epithet 'She-Wolf of France' in The Bard (1757); and - as late as 1967 - Kenneth Fowler describing her as 'a woman of evil character, a notorious schemer'. How, then, did Isabella acquire such a reputation?

Isabella certainly lived adulterously with Roger Mortimer for at least four years. But the evidence surrounding accusations of murder and regicide is unsubstantiated. Thus what has condemned Isabella is her sexual transgression. Had it not been for her unfaithfulness, history may have immortalised her as a liberator - the saviour who unshackled England from a weak and vicious monarch and helped put a strong king on the throne.

In this, the first, full-length biography of Isabella, Alison Weir revisits the facts of Isabella's life in a scholarly context in which women's personal lives do not dictate wholly the way we interpret their roles in the public world. A dramatic and startling biography which will change the way we think of Isabella and her world for ever.

Random House UK Newsletter, 2005

Once again, I have the pleasure of writing for the Alison Weir Newsletter. This latest edition marks the publication of my new book, Isabella, She-Wolf of France, Queen of England, the first full-length biography of Edward II's wife. Back in the 1970s, after I had completed the original version of the work that would later be published as The Six Wives of Henry VIII, I embarked on a vast research project on England's medieval queens from the Norman Conquest to the dawn of the Tudor age. Some of the lives of these long-dead women are poorly documented and of peripheral popular interest, but among them, some formidable and fascinating characters stand out. One is Eleanor of Aquitaine, whose biography I published in 1999; it proved to be my most successful book up to that time. I had never realised there was so much public interest in - and, indeed, affection for - that remarkable and dynamic woman, one of the towering figures of the Middle Ages.

I covered the lives of other interesting mediaeval consorts whom I had researched - Katherine of Valois, Margaret of Anjou, Elizabeth Wydeville and Anne Neville - in my books on the Wars of the Roses, but I was always aware that there was one queen whose story was so incredible that it needed to be told, yet who had enjoyed such a bad reputation for seven centuries that any attempt at an objective assessment might be doomed to failure. That queen was the notorious Isabella of France, who is better known as 'the She-Wolf of France', a nickname given her in the eighteenth century.

Back in 1981 I began work on a life of Isabella, but at that time historical biography was not so commercial a genre as it is now, and my book - half-written - was rejected on the grounds that it probably would not sell many copies. Twenty years later, after the success of Eleanor of Aquitaine, and in a very different literary climate, I was at last commissioned to write a biography of Isabella, and set about my task with mixed feelings. Hers was an incredible story, it is true, yet I could feel little empathy for my subject. No one, I had found, had anything good to say about her.

I was fortunate from the beginning to be given invaluable support by the historian and novelist P.C. Doherty, who generously sent me a copy of his unpublished 1977 thesis on Isabella, and the proofs of his forthcoming book, Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II. I was surprised to hear him say that he had enormous sympathy for Isabella, because that seemed at variance with what I knew of her. To my knowledge, she was an adulteress, a tyrant and a murderess, and writing her life was going to be comparable to writing a life of Messalina or Salome.

As my research progressed I began to question the accepted views of Isabella, but it was only when I began to write her story that I began to think about challenging them, because a close analysis of the sources showed that not only was she for many years a model queen-consort who earned golden opinions and a reputation as a peace-maker, but that she was also deeply wronged and cruelly treated, and that, for her own safety and the good of the realm, she had no choice but to make the fateful decisions that would lead to a political and constitutional revolution in England and, ultimately, her own downfall.

I also came to the realisation that there were many parallels to be drawn between Isabella's life and experiences and those of Eleanor of Aquitaine. Both were healthy, beautiful, feisty, strong-willed women; both had considerable political ability; both were married at some stage to weak men; both committed adultery; both were ambitious for their sons; both led rebellions against their royal husbands - Isabella mounted the first successful invasion of England since the Norman Conquest - and both were imprisoned for it. Both ruled England, more or less autonomously, for a time, and both ended up dying respected and regarded as elder stateswomen, having taken religious habits. Both were the subject of lurid myths and legends, and both were accused by later generations of murder. What struck me forcibly though, as these similarities emerged, was that, while Eleanor, that flawed but fascinating woman, enjoys today a wonderful reputation and is held in great esteem and affection by many, Isabella, who was equally dynamic, flawed and fascinating, and deserving of sympathy, remains the evil queen of legend.

It is the charge of regicide - the murder of the King her husband - that has so tainted Isabella's reputation. For centuries, it has been believed that she was a party to Edward II's allegedly brutal death in 1327, and even that she actively plotted it. Nowadays, research has cast doubt on whether Edward II was murdered at all, yet even if he was, it is highly unlikely that Isabella was a party to it.

What is not in doubt is that Isabella lived in adultery for five years with her lover, Roger Mortimer. That alone was enough to ensure the censure of the medieval chroniclers and, following in their wake, generations of historians. But it was neither her adultery, nor any accusations of murder, that brought Isabella down. It was her unpopular political decisions, which earned her such opprobrium and hatred that thereafter all her policies had to be aimed at keeping herself and her lover in power. As Isabella fell more and more in thrall to him, Mortimer became increasingly tyrannical. The consequences, for her, were catastrophic.

It is all too tempting to take a modern viewpoint of Isabella. Today, in an age in which self-fulfillment is the new morality, she would be applauded for taking a stand against her husband, and her liaison with Mortimer would be seen as self-empowering and liberating. Yet the conventions of her own time demanded that a woman be faithful and loyal to her husband, however badly she was treated. The contemporary tale of' Patient Grizelda' (which Chaucer recounts in 'The Clerk's Tale') illustrates this perfectly: Grizelda remains loving and true despite being cruelly tested by her husband Walter. For years, Isabella played Grizelda to Edward's Walter, but then a vicious man came between them, probably in every sense, and Isabella's years of trial began. Unlike Grizelda, this proud daughter of France retaliated in the end, to spectacular effect.

To my surprise, by the time I finished the book, I found myself, like P.C. Doherty, enormously sympathetic towards Isabella; I also conceived great admiration for her. Like Eleanor of Aquitaine, she was a remarkable woman.

Writing a biography of a medieval subject like Isabella is essentially the piecing together of fragments of information, analysing the results, making sense of them and pulling everything together into a cohesive framework. It's also a matter of getting the balance of the story right. For example, we have virtually no information about Isabella's childhood, only sparse and patchy evidence for her thirteen years as queen consort, volumes of sources for the five years from her rebellion to her fall, and then only the odd glimpse of her during the last twenty-eight years of her life. It's therefore important to ensure that equal attention is given to the years for which sources are scanty as to the years for which they are plentiful.

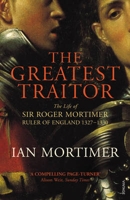

I'm aware that some of my conclusions may prove controversial. Both P.C. Doherty and lan Mortimer (whose book on Roger Mortimer, The Greatest Traitor, also proved very helpful, as did its author), after exhaustive study, found good reason to doubt that Edward II was murdered, although both reached different conclusions. They were not the first to question the accepted tale of the King's death; as far back as the nineteenth century, historians had raised questions doubts about it. Yet even today some remain dismissive about the evidence for the King's survival. I myself was a rampant sceptic - until I read Doherty's and Mortimer's books, and looked at the evidence for myself. The fact remains that there are still unanswered questions about the so-called murder and its aftermath, that cannot be ignored, and those doubting historians should know better than to insist that the debate should be closed. No one can say with certainty what happened to Edward II, but his survival is at least a possibility.

Naturally I did an enormous amount of background research on the period, and I have been familiar with the world of the fourteenth century for more decades than I care to remember. However, because I had so much to say about Isabella, I have included only sufficient background detail to set her story in context. It would not be appropriate, for example, to give long accounts of the wars with Scotland because, apart from on one or two hair-raising occasions, Isabella had relatively little to do with them. Of course, when she became involved in the political life of the kingdom, her story becomes in many respects the history of England itself, yet this remains very much a biography, and the focus is on the personal rather than the political.

As I hope I have made clear, I did not set out to write a revisionist life of Isabella of France. As always, I assess the evidence before reaching any conclusions. In this case, against all expectations, I have written a largely sympathetic biography, which I sincerely hope presents a more realistic view of a woman who, in my opinion, has been greatly maligned.

WHAT'S NEXT? from the 2003 ALISON WEIR NEWSLETTER

The film 'Braveheart', starring Mel Gibson and Sophie Marceau, featured not only stunning battle scenes, but also a poignant love story between William Wallace and Isabella of France, the wife of the heir to the English throne (the future Edward II). Such a love was inevitably doomed, for Isabella, although beautiful and spirited, was trapped in a loveless marriage to a homosexual, while Wallace, the brave leader of Scottish resistance to Edward I's territorial ambitions, would end up suffering the barbaric death meted out to traitors. The film ends, however, with a poetically just hint that the child Isabella was then carrying, the future Edward III, was in fact fathered by Wallace.

All very stirring stuff, but nothing could be further from the truth. Wallace was executed in 1305, and Isabella did not come to England until 1308, after her marriage to Edward II, who had succeeded his father Edward I the previous year. Their eldest son, the future Edward III, was not born until 1312. Isabella therefore had nothing to do with Wallace. Thus are historical facts sacrificed in the interests of commercialism.

The fact is that Isabella's story is fascinating in its own right, not only because of who she was, but also because of what she did. The spoiled only daughter of King Philip IV of France, he who ruthlessly suppressed the Order of the Knights Templars, Isabella was nicknamed 'the Fair' because of her beauty. Her marriage was brought about to cement a peace between England and France, who were ancient enemies.

Isabella was about 12 at the time of her wedding; her bridegroom, Edward II, was 24, and his interest in rustic, unkingly pursuits and handsome young men had long given his father and his advisers cause for concern. Historians nowadays question whether Edward was truly homosexual. What is certain is that the young Queen was furious to find herself eclipsed at court by a flamboyant Gascon, Piers Gaveston, with whom Edward was apparently besotted, and who thereby incurred the hatred of the chief nobles, whose position he was usurping in the King's

counsels. Gaveston's outrageous career came to a bloody end in 1312, when he was summarily executed by the King's cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster.

Later that year, Isabella bore her first child, the future Edward III. The marriage produced three other children: John of Eltham in 1316, who died at the age of 20; Eleanor in 1318, who became the wife of the Duke of Gueldres; and Joanna in 1321, who was married as a child to David II of Scotland. But these were turbulent years. In 1314, Edward It's reputation hit its nadir when he was decisively and humiliatingly defeated by King Robert the Bruce of Scotland at the battle of Bannockburn. Years of famine followed, and there was increasing tension between the King and his lords, and later between Edward and Isabella, chiefly on account of the fact that Gaveston had been replaced in the royal affections by Hugh le Despenser, who not only became the King's chief adviser but also seized every opportunity to slight the Queen.

Driven beyond endurance, Isabella seized her chance to escape when she undertook a diplomatic mission to France in 1325. After her business was completed, she refused to return to England, and then took a lover, Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, a powerful Marcher baron who had offended the King and been imprisoned in 1323 in the Tower of London. Mortimer was ruthless, clever and power-hungry, and he was one of the few prisoners who ever escaped from that secure fortress. In 1324 he sought refuge in France, and it was at the French court, during Isabella's visit in 1325-6, that their affair began.

With help from the Count of Hainault, Isabella and Mortimer raised an army, their purpose being ostensibly to oust Hugh le Despenser from his entrenched position of power. When they landed with their force in England, however, it soon became clear that their mission was nothing less than the deposition of Edward II. Despenser was taken and violently put to death, and the King, when his wife's army eventually caught up with him, was taken prisoner. In January 1327 he was forced to abdicate, and his eldest son, then aged 14, was proclaimed King Edward III in his stead. As young Edward was a minor, Isabella and Mortimer ruled in his name.

The deposed Edward II was kept - it was said - in increasingly vile conditions at Berkeley Castle, it being the hope of his gaolers that he might succumb to the rigours of his captivity, for there were several moves to restore him; but his superb constitution ensured his survival, albeit in abject misery. Finally, in September 1327, it was given out that the former King was dead. Several chroniclers claimed that he had been brutally murdered, but in such a way as to leave no mark on his body.

The extent of Isabella's involvement in her husband's murder is a matter of debate; her guilt was never exposed nor proven. She did not marry Mortimer, who was undoubtedly responsible for the deed, but continued to rule with him until November 1330, when her son, then nearly 18, declared himself of age.

Edward III bitterly resented Mortimer, and feared for his mother's reputation. One night in October 1330, he and a group of aristocratic friends passed through the honeycomb of secret passages beneath Nottingham Castle and gained access to the Queen's apartments. Bursting in, they surprised Isabella and Mortimer. Mortimer was seized, as the Queen screamed, 'Fair son, fair son, have pity on the gentle Mortimer!' But Edward was determined to rid himself of the tyrant, and had Mortumer publicly executed soon afterwards. His mother he sent into honourable retirement at Castle Rising in Norfolk, where she was accorded all the respect and comforts due to a queen dowager. The legend that she lost her sanity at this time may have some basis in fact.

In time the scandal died down, and Isabella was allowed to visit court, and even play a minor role in public affairs. She also took an interest in her growing number of grandchildren, one of whom was named after her; another, the Black Prince, sometimes visited her. When the last Captain King of France died in 1328, Isabella, his surviving sister, might have claimed the French crown, but the Salic law prevented inheritance by a female, and the succession went to her Valois cousin. Nevertheless, in 1338, Edward III, by virtue of his descent from Isabella, claimed the throne of France, thus starting the Hundred Years War. When Isabella died in 1358, she was buried in the manstery of the Greyfriars in Newgate, London, with Edward II's heart at her breast. Both her tomb and the monastery have long since disappeared, but her reputation as 'the She-Wolf of France' has endured. The question is, did she deserve it?

In the 1970's, I researched the lives of all the medieval queens of England, and I have drawn on that research for several other books, notably Lancaster and York, The Princes in the Tower and, more extensively, Eleanor of Aquitaine. At events, when the matter of future projects has arisen, many people have kindly said how much they enjoyed Eleanor of Aquitaine and have urged me to write a book about another medieval queen. This is it. I have long been fascinated by Isabella's story, and carried out further research in 1981-2, with a view to writing her biography. Several chapters were completed, but I now write very differently and am currently reappraising the source material and carrying out a great deal of further research. As I have outlined above, there are several issues that need resolving, particularly the questions of Edward II's sexuality and Isabella's involvement in his murder.

This is a riveting story with a compelling mystery - we don't even know for certain that Edward II did die at Berkeley Castle in 1327 - and I hope it will become a fitting companion volume to Eleanor of Aquitaine.

ISABELLA OF FRANCE

The Life of a Mediaeval Queen

Alison Weir

U.S. jacket copy

Acclaimed historian and bestselling author Alison Weir, who has delighted readers with such masterpieces as ELEANOR OF AQUITAINE, turns her expert eye to the dark and tragic tale of the notorious "She-Wolf of France".

The only daughter of France"s King Philip IV, Isabella married the English King Edward II in 1308, at the age of 12, to cement a peace between France and England. The marriage soured quickly; Edward was more interested in his young male courtiers than his bride and his kingdom. Her patience exhausted, Isabella fled with her eldest son back to France, and into the arms of her husband's enemy, the powerful baron, Roger Mortimer. Together, they raised an army, forced Edward II to abdicate, and then, it was later asserted, had him brutally murdered. Isabella and Mortimer then ruled England during the minority of her son, Edward III.

A work of extraordinary scholarship, ISABELLA OF FRANCE offers groundbreaking insights into the life and reputation of this most villified of gueens, a woman who was in her own way as charismatic, compelling and complicated as Eleanor, that other great mediaeval queen.

Above: Preliminary US paperback jacket designs and images.

ISABELLA, SHE-WOLF OF FRANCE, QUEEN OF ENGLAND

* Isabella of France has for nearly 700 years been the most villified of English queens; her reputation as an adulteress and murderess led to her becoming universally known as vthe She-Wolf of France'.

* Married at twelve in 1308 to the homosexual Edward II, Isabella grew up to be a legendary beauty but found herself largely neglected by her weak husband and cruelly slighted by his vicious favourites. In 1325, with her liberty, her children and her income taken from her, she managed to escape to France, where she began an affair with an exiled traitor, Roger Mortimer. Together, they led the only successful invasion of England since the Norman Conquest, deposing Edward and setting themselves up as regents for Isabella's eldest son, Edward III. Isabella was long believed to have been an accessory to Edward II's brutal murder in 1327, but recent recearch has cast serious doubt on whether that murder ever took place. Even so, Mortimer was a ruthless schemer, and Isabella, despite her sensible and pragmatic policies, quickly became in thrall to him. In 1330, Edward III came of age and overthrew the regime of Isabella and Mortimer. Mortimer was executed, and Isabella spent the last three decades of her life in honourable retirement.

* Isabella's reputation rests largely on the prejudices of medieval monkish chroniclers and Victorian historians. An examination of contemporary records reveals many of her finer qualities, and changing social attitudes now enable a more tolerant and sympathetic approach to Isabella's personal relationships.

* Isabella has also been the subject of several lurid legends, among them the ambiguous Latin instructions to Edward II"s murderers, the spurious tale of the red-hot poker and stories of the shrieking mad ghost of Castle Rising. Significant mysteries surround her: was she sexually humiliated by Edward's favourites? Did she conceive bastard children by Mortimer? And how far was she involved in the fate of Edward II? Recent books on this subject II have tended to focus on Mortimer's role rather than Isabella's.

* Alison Weir addresses all these issues in this book, the first full biography of Isabella to be published since Agnes Strickland wrote The Lives of the Queens of England in the 1840s, and in it she has effectively debunked the legends and propaganda, stripped away centuries of romantic myth, and produced a vivid and realistic portrayal of Isabella and the violent mediaeval world in which she lived. Isabella emerges from these pages every bit as vigorous and capable as Eleanor of Aquitaine, with whom many parallels may be drawn: like Eleanor, she faced adversity and hardship; like Eleanor, she was highly sexed and trapped in a frustrating marriage; like Eleanor, she took a lover; like Eleanor, she led a rebellion against the King her husband; like Eleanor, she was adept at statecraft; and like Eleanor, she was controversial in her own day. Unlike Eleanor, however, she does not enjoy a brilliant posthumous reputation. This book seeks to go some was towards redressing that, and to rehabilitate the memory and reputation of a remarkable yet grossly maligned woman, who was the victim, not of her own wickedness, but of circumstances, unscrupulous men and the sexual prejudices of those who chose to record her story.

ISABELLE OF FRANCE

Original book proposal

(A decision was taken afterwards to use the anglicised version of the Queen's name, Isabella)

The film 'Braveheart', starring Mel Gibson and Sophie Marceau, featured not only stunning battle scenes, but also a poignant love story between William Wallace and Isabelle of France, the wife of the heir to the English throne (the future Edward II). Such a love was inevitably doomed, for Isabelle, although beautiful and spirited, was trapped in a loveless marriage to a homosexual, while Wallace, the brave leader of Scottish resistance to Edward I's territorial ambitions, would end up suffering the barbaric death meted out to traitors. The film ends, however, with a poetically just hint that the child Isabelle was then carrying, the future Edward III, was in fact fathered by Wallace.

All very stirring stuff, but nothing could be further from the truth. Wallace was executed in 1305, and Isabelle did not come to England until 1308, after her marriage to Edward II, who had succeeded his father Edward I the previous year. Their eldest son, the future Edward III, was not born until 1312. Isabelle therefore had nothing to do with Wallace. Thus are historical facts sacrified in the interests of making a commercial film.

But Isabella's story is fascinating in its own right, not only because of who she was, but also because of what she did. The spoiled only daughter of King Philip IV of France, he who ruthlessly suppressed the Order of the Knights Templars, Isabelle was nicknamed 'the Fair' because of her beauty. Her marriage was brought about to cement a peace between England and France, who were ancient enemies. Isabelle was about 16 at the time of her wedding; her bridegroom, Edward II, was 24, and his interest in rustic, unkingly pursuits and handsome young men had long given his father and his advisers cause for concern. Historians nowadays question whether Edward was truly homosexual, which is a subject that needs further exploration. What is certain is that the young Queen was furious to find herself eclipsed at court by a flamboyant Gascon, Piers Gaveston, with whom Edward was apparently besotted, and who thereby incurred the hatred of the chief nobles, whose position he was usurping in the King's counsels. Gaveston's outrageous career came to a bloody end in 1312, when he was summarily executed by the King's cousin, Thomas, Earl of Lancaster, assisted by Guy, Earl of Warwick. Later that year, Isabelle bore her first child, the future Edward III.

The marriage produced three other children: John of Eltham in 1316, who died at the age of 20; Eleanor in 1318, who married the Duke of Gueldres; and Joanna in 1321, who was married as a child to David. II of Scotland. But these were turbulent years. In 1314 Edward II's reputation hit its nadir when he was decisively and humiliatingly defeated by Robert the Bruce at the Battle of Bannockburn. Years of famine followed, and there was increasing tension between the King and his lords, and between Edward and Isabelle, chiefly on account of the fact that Gaveston had been replaced in the royal affections by Hugh le Despenser, who not only became the King's chief adviser but also seized every opportunity to slight the Queen.

Driven beyond endurance, Isabelle appears to have taken a lover. The man in question was Roger Mortimer of Wigmore, a powerful marcher baron who had offended the King and been imprisoned in the Tower of London. Mortimer was ruthless, clever and lecherous, and he was one of the few prisoners who ever escaped from that secure fortress. He sought refuge in France, and it was at the French court, during Isabelle's visit in 1326, that their affair probably began. The Queen was in Paris with Prince Edward, who had come to swear fealty to the French King for his lands in France.

The prospect of returning to England, however, was one that Isabella could not endure, and with help from Hainault she and Mortimer raised an army, their purpose being ostensibly to oust Hugh le Despenser and his family from his entrenched position of power. When they landed with their force in England, however, it became clear that their mission was nothing less than the deposition of Edward II. Despenser was taken and violently put to death, and the King, when his wife's army eventually caught up with him, was imprisoned in Berkeley Castle in Gloucestershire. In January, 1327, he was forced to abdicate, and the young Edward III, then aged 14, was proclaimed King in his stead. As Edward was a minor, Isabella and Mortimer set themselves up as joint regents.

The deposed Edward II was said to have been kept in increasingly vile conditions at Berkeley Castle; allegedly the regents hoped that he might succumb to the rigours of his captivity, fearing there might be moves to restore him, but his superb constitution was supposed to have ensured his survival, albeit in abject misery. Finally, in September 1327, a cryptic message is said to have been sent to his custodians - cryptic because a vital comma was left out, leaving the message open to two interpretations. Translated from the Latin, it read either, 'Edward kill not, to fear the deed is good', or 'Edward kill, not to fear the deed is good'. It was said that the King's gaolers perceived that the regents wanted him out of the way, so they murdered him by thrusting a red-hot poker up into his bowels - a punishment many have interpreted as being a fitting end for one who was believed to have repeatedly committed what contemporaries viewed as the sin of sodomy, and which some believe reflected the vengeful anger of his spurned wife.

The extent of Isabelle's involvement in her husband's murder is a matter of debate; her guilt was never exposed or proved. She did not marry Mortimer, who was undoubtedly responsible for the deed, but continued to rule as co-regent with him until November 1330, when her son, at 18, attained his majority.'

Edward III had been fond of his father, and sincerely mourned his loss. He resented Mortimer, and feared for his mother's reputation. One night in November 1330 he and a group of aristocratic friends passed through the honeycomb of secret passages beneath Nottingham Castle and gained access to his mother's apartments. Mortimer was seized, and the Queen cried to the young King, 'Fair son, fair son, have pity on the gentle Mortimer!' But Edward was determined to rid himself of the tyrant, and had him publicly executed soon afterwards. His mother he sent into honourable retirement at Castle Rising in Norfolk, where she was accorded all the respect and comforts due to a Queen Mother.

In time, the scandal died down, and Isabelle was allowed to visit court, where she took an interest in her growing number of grandchildren, one of whom was named after her. When the line of the Capetian kings of France died out in 1328, Isabelle might have claimed the French crown, but the Salic law prevented inheritance by a female. Nevertheless, in 1338, Edward III, by virtue of his descent from Isabelle, claimed the throne of France, thus starting the Hundred Years' War. When Isabelle died in 1358, she was buried in the monastery of the Greyfriars in Newgate, London. Both her tomb and the monastery have long since disappeared, but her reputation as 'the She-Wolf of France' has endured.

Surprisingly, there has never been a full-length biography of Isabelle of France. In the 1850s she featured in The Lives of the Queens of England by Agnes Strickland, who thought that many of the details of her life were too shocking to bear repetition, and in the 20th century there were just one or two scholarly articles about her in historical journals.

In the 1970s I researched the lives of all the medieval queens of England, and I have drawn on this research for several other books, notably Lancaster and York, The Princes in the Tower and, more extensively, Eleanor of Aquitaine. At bookshop events, when the matter of future projects has arisen, many people have kindly said how much they enjoyed Eleanor of Aquitaine and have urged me to write a book about another medieval queen. Since I prefer to write about strong women who led interesting and eventful lives, I believe that Isabelle would be an ideal subject. I have long been fascinated by her story, and carried out further research in 1981-2, with a view to writing her biography. Several chapters were completed, but I now write very differently and would wish to reappraise the source material and carry out a great deal of further research before writing such a book. I would like to undertake a comprehensive reappraisal of Isabelle's life, in order to arrive at a more accurate estimation of her deeds and her character. As I have outlined above, there are several issues that need resolving, particularly the questions of Edward II's sexuality and Isabelle's involvement in his murder. I also wish to explore the relationship between them. I know from my research that the sources for the period are extensive and revealing, and that colourful contemporary detail would enhance a riveting story.

From Heritage Today, the magazine for members of English Heritage, September 2005:

Queen Isabella, wife of Edward II, is infamous as 'the She-Wolf of France' - deposer and even murderer of her husband. But, says Alison Weir, this is a reputation entirely undeserved.

Lurid legends are told of the brooding stronghold of Castle Rising Casde in Norfolk. It is said that the ghost of die evil and mad 'She-Wolf' Queen Isabella, who was imprisoned there in the fourteenth century, can be heard wailing and shrieking hysterically in the upper levels of the ruined keep. The story is related that, having been a party to die murder in 1327 of her husband, Edward II, she ruled England as a tyrant with her lover, Roger Mortimer. But, when they were overthrown and he was executed in 1330, Isabella lost her reason and spent the 28 remaining years of her life immured within these walls, suffering agonies of grief and remorse.

It's a compelling tale, and it has been retold so often that most people accept it as fact - and few think to question it. But question it we should, because a closer investigation of Isabella's life reveals that there is hardly a shred of evidence to support this colourful story.

Isabella of France, who lived from 1295 to 1358, and who married Edward II in 1308 and became by him die mother of Edward III, was neither evil nor mad. Historians now doubt whether Edward II was murdered at all, in which case Isabella could not have been a party to his allegedly brutal end. And her stay at Castle Rising was not as a prisoner.

Truth, it has been said, is often far more interesting than fiction. And as a result of researches for my new book, Isabella, She-Wolf of France, Queen of England, I found - to my surprise - much to admire in this most vilified English Queen. Married at only 12 years of age to the reputedly homosexual Edward II, the beautiful Isabella proved a loyal and supportive wife for many years, even though her handsome but weak husband often neglected her for his male favourites. Her rare but judicious forays into the turbulent politics of the age earned her a reputation as a peacemaker, and her husband respected her abilities sufficiently to entrust her with diplomatic missions to France. She bore Edward four children and proved a loving and devoted mother. Everyone spoke highly of her.

So what went wrong? How could such a paragon come to deserve such a bad reputation? The rot had set in by 1322, by which time Edward had come to be in thrall to the power-hungry, unscrupulous and vicious Earl of Winchester, Hugh le Despenser. Despenser resented the queen's influence and was determined to remove her from power. Systematically - and with the king's full co-operation - he deprived Isabella of her income, her servants, her children and her liberty. By 1325 she was a prisoner in her own household, watched constantly by Despenser's spies, and fearful because of threats to her life.

Providence moved in her favour, though, and in that year it became clear that it was necessary for Isabella to undertake a peace mission to France. Reluctantly, Edward and Despenser let her go. This proved to be a fateful decision: once in France, Isabella cleverly arranged for her eldest son to be sent to her, to play his part in the diplomatic negotiations. When these were completed, being in the advantageous position of having the heir to England in her custody, she refused to return to England on the grounds that her life would be in danger from Despenser. In vain did Edward plead with her to return.

Backed by her brother, the King of France, Isabella stood firm. She began to dress as a widow, insisting that Despenser had wrecked her marriage. She then became involved, both politically and sexually, with an exiled English traitor, Roger Mortimer, who had escaped from

the Tower of London and sought refuge in France. Mortimer and other exiles had been working for the overthrow of the corrupt Despenser, and Isabella soon joined them in formulating plans for an invasion of England. These plans matured satisfactorily and the Queen's fleet landed in Suffolk in the autumn of 1326. What followed was a triumphant progress through England, as Edward II's dwindling support evaporated and he fled west to Wales with Despenser. Isabella's army pursued them and, in November 1326, Despenser was taken and executed with appalling brutality as a traitor.

By now, Isabella and Mortimer had seized power in the name of the young Prince Edward, and it was clear that their agenda encompassed more than the destruction of Despenser. After Edward II was captured in November and imprisoned in Kenilworth Castle, the Queen and her supporters put pressure on him to abdicate, taking care to cloak the process with as much legality as possible. His deposition - the first of an English king since the Norman Conquest of 1066 - was effected in January 1327, and the young Edward III was immediately crowned. The removal of Edward II was a popular move, for his reign had been one long catalogue of disasters, and Isabella and Mortimer began the period of their effective regency on a tide of national approval.

This was not to last, for their foreign policies proved a step too pragmatic for contemporary opinion. When Isabella brought about a peace with Scotland, recognising Robert the Bruce as king and so bringing to an end a financially crippling war that could not be won, her popularity slumped. It was this - not rumours of her involvement in Edward II's death in September 1327 - that undermined her regime. Thereafter, her policies were all aimed at keeping her and Mortimer in power, which served only their interests and made the two of them more hated still.

In 1330, when Edward III came of age, he staged a coup that ended in Mortimer's execution and his mother's imprisonment at Windsor.

Edward's filial devotion ensured that no blame attached to Isabella's name: Mortimer was made the scapegoat for their misgovernment. It was also beyond doubt that Mortimer had given orders for the annihilation of Edward II. However, given the circumstances at the time, Isabella could not have anticipated or known of this. Whether Edward II was in fact murdered is a matter for debate, and new evidence suggests that he may have escaped from his prison and ended his days as a hermit in Italy. This is to be found in a letter written by an Italian priest, Manuele Fieschi, to Edward III; historians have never been able satisfactorily to explain how Fieschi came by his information, unless it was from the mouth of Edward II himself.

Isabella stayed for two years under house arrest at Windsor, nobly attended and honourably housed. The records suggest she was attended by a physician, and it has been suggested that she suffered some kind of breakdown after Mortimer's execution. But she was released in 1332, and in her conduct thereafter there is nothing to suggest that she was in any way mentally incapable or unstable. It may be that her release coincided with her recovery.

During her remaining years, she lived the life of a respected queen mother. Castle Rising was one of the residences she favoured, and she stayed there often, maintaining great state and demanding gifts of wine and food from the long-suffering burghers of nearby King's Lynn. Edward III visited her at Rising several times. It is clear that she moved around freely, staying at other houses she owned and occasionally attending court. As the years passed, she regained much of the respect she had enjoyed as queen consort; she was included in prayers with the royal family in churches, and her opinion was sought on political matters.

In the final year of her life, Isabella became a lay member of the Order of St Francis; she was buried in the habit of the Poor Clares, and in her wedding cloak. This suggests that her thoughts were with her late husband, and that she had come to think more sympathetically of him in her twilight years. She died, not at Castle Rising, as is so often claimed, but at Hertford Castle, whence her body was conveyed to the Grey Friars' church in London for burial. That church and Isabella's tomb were destroyed in the sixteenth century, but a stone inscribed 'Isabella' in the church at Castle Rising may mark the place where her heart is buried.

So, how did Isabella acquire her shocking reputation? For 700 years monkish chroniclers and moralistic historians have censured her largely on account of her adulterous relationship with Mortimer. The nickname 'She-Wolf of France' was actually invented by Shakespeare for Margaret of Anjou, but in the eighteenth century, when England was at war with France, the poet Thomas Gray bestowed it on Isabella, who by then was regarded as the epitome of all that was evil in a queen. But today we have more relaxed views about personal relationships, which permits a new and more compassionate understanding of the situation in which Isabella found herself. We also have the benefit of new research that strongly suggests she was not, after all, the murderess of long repute.

It is time to forget the legend of the demented wraith screaming in the corridors of Castle Rising - a legend with no basis in fact - and to remember instead the considerable abilities and qualities of this most maligned of English queens, who held court and lived in unprecedented luxury in that once-splendid castle now in the care of English Heritage.

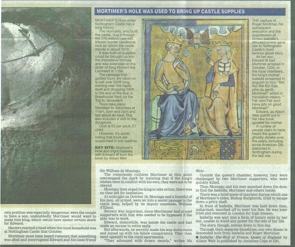

From the Nottingham Evening Post, September 2005:

Seventeen-year-old Edward III risked all to secure his crown, as he set out to overthrow his own mother, Queen Isabella, and her ruthless lover, the powerful Roger Mortimer, at Nottingham Castle. A new book tells what really happened that night in October, 1330. JOHN BRUNTON also talks to author Alison Weir about the terrible fate awaiting England had the daring plan failed

England's future hung in the balance one night in October 1330. One way or another the outcome would be decided abruptly within the great fortress walls of Nottingham Castle. In those days it was still a major fortification. Look at Warwick Castle now and you get some idea of Nottingham then. And it was here that the queen mother, Queen Isabella, 35, whom history has nicknamed the She-Wolf of France, was staying with her ruthless and by now hated lover, Roger Mortimer, 43, the 1st Earl of March. The two had swept to power after the murder of Isabella's husband Edward II. It was said he had died a horrible death with a red-hot poker thrust via his rectum into his bowels. Many said Mortimer had ordered the grisly execution. Afterwards, having suppressed the power of the barons - Mortimer and Isabella had seen to it that Edward II's own brother, the Duke of Kent, was executed - there was apparently no one to oppose them, including the late King's own son, the new monarch, Edward III, who was 17. But as Isabella and Mortimer plundered the country's wealth, treating England like their own private casino, they hadn't counted on the steely will of young Edward.

The story of their downfall is told in a new book on the Nottingham legend of Mortimer's Hole. Acclaimed author Alison Weir has penned the first full published biography of Edward II's adulterous widow, Isabella: She-Wolf of France, Queen of England. At its heart is a story of overweening ambition and power, with Isabella, daughter of Philip IV, king of France - in his day the most powerful sovereign in Europe - at its centre.

Her husband, the bisexual Edward II had neglected her. Although she had borne him four children, it seems clear that Edward preferred the company of his male friends. And by the early 1320s prime among these was the utterly ruthess and unprincipled Hugh Despenser, egged on by his father, also Hugh. Despenser had ensured that Isabella was effectively penniless and powerless. She had no choice but to take forced exile in France.

It was there she began her scandalous affair with Mortimer, who himself had fled the Tower of London where he was being held for treason. In 1326, backed by just 700 foreign mercenaries, Isabella and Mortimer landed in England and took the reins of power from Edward II. The Despensers were executed and the king taken into custody. He was later murdered, and replaced by Edward III. But the real power lay in Mortimer and Isabella's hands and, as they misused it, Edward III was compelled to act. It was also believed, too, that by autumn 1330, Isabel was pregnant by Mortimer. The author thinks this may have been the case, and if this was so, Edward must have reasoned his own position was especially dangerous; were the couple to have a son, undoubtedly Mortimer would want to make him king, which would have meant certain death for Edward.

Matters reached a head when the royal household was at Nottingham Castle that October. Mortimer must have heard rumours that something was afoot and interrogated Edward and his close friend, Sir William de Montagu. The relentlessly ruthless Mortimer at this point overstepped the mark by insisting that if the King's wishes were in conflict with his own, they were not to be obeyed. Montagu then urged the King to take action; there was no time left for hesitation.

At midnight on October 19, Montagu and a handful of his men, all armed, were let into a secret passage to the castle keep, helped by its deputy constable, William d'Eland. Secrecy was important, since Mortimer had armed supporters with him who needed to be bypassed if the plan was to work. Edward, meanwhile, was inside the castle and had made an excuse to retire early. But afterwards, he secretly made his way downstairs and joined up with his fellow conspirators. They then went upstairs to the royal apartments.

"They advanced with drawn swords," writes Ms Weir. Outside the queen's chamber, however, they were challenged by two Mortimer supporters, who were quickly killed. Then Montagu and his men smashed down the door, to find the Isabella, Mortimer and others inside. There was a brief scene of mayhem during which one of Mortimer's aides, Bishop Burghersh, tried to escape down a privy shaft. In front of Isabella, Mortimer was held down then, unharmed, marched off to meet his fate. He was later tried and executed in London for high treason.

Isabella was sent into a form of luxury exile by her son, unable to wield any power for the rest of her life.

The story, though, echoes down to this day. Through their separate bloodlines, our own Queen is descended both from Isabella and Roger Mortimer.

CLOSE ESCAPE FROM ANARCHY

Author Alison Weir is in no doubt that had Edward Ill's daring plan to capture Roger Mortimer, Earl of March, at Nottingham Castle in 1330 failed, the country would have been plunged into anarchy. Mortimer, meanwhile, would have ordered Edward's death, even though Queen Isabella, who adored the Earl of March, was Edward Ill's mother.

"He would have been done away with," says Ms Weir. "He couldn't have been executed judiciously, there was no mechanism. But it seems likely Mortimer, who had ordered the execution of Edward II, would have wanted Edward III out of the way too."

The country would then have dissolved into chaos. "Isabella and Mortimer's sole policy was to stay in power, and that had already made them vastly unpopular. But because there was no effective opposition to them - it had been eliminated - there would have been no alternative but complete anarchy and chaos," says Ms Weir. History, then, would have taken a vastly different turn.

As it was, the people of Nottingham were overjoyed that Mortimer and his key supporters had been arrested. Ms Weir notes: "The lords and people gathered to watch as he and other prisoners were escorted through Nottingham, and at his approach they shouted loudly." The following day, in Nottingham, Edward issued a public proclamation about the arrest, announcing at the same time he had taken personal control of the government of his realm.

FROM HAVEN TO HELL

Nottingham Castle was the scene of Isabella's downfall. Yet 12 years earlier, in 1318, it was a safe haven, to which she had fled for her own protection. Pursuing his campaign against the Scots, whose army under Robert the Bruce had so humiliatingly defeated Edward II at the Battle of Bannockburn, King Edward had left his wife near York while he'd gone to Berwick-on-Tweed. But while he was there, the legendary Scottish hero, Sir James Douglas, better known to history as 'the Black Douglas', was having the time of his life raiding lands in northern England unopposed, backed by 10,000 armed men. He set his sights on kidnapping the Queen; it would have given the Scots unbeatable bargaining power. But Isabella came to hear of what was to befall her, pretty much at the last minute, and escaped to safety, before fleeing south to Nottingham. Alison Weir writes that she was then taken by water to Nottingham, "where she probably sought refuge in the castle". The narrowest of escapes.

Mortimer's Hole under Nottingham Castle has a long history. The Normans, who built the castle, dug it through the 270-million-year-old triassic bunter sandstone rock on which the castle stands in about 1070. It was built so that supplies could be brought up into the impressive fortress, and was extended on the order of King Richard the Lionheart in 1194. The passage that guided tours are taken on is just over 300ft long, starting near the castle itself and dropping 140ft to the end of the tour, in Brewhouse Yard, by the Trip to Jerusalem pub.

The capture of Roger Mortimer, his subsequent execution and the suppression of Queen Isabella's misused power gave rise to Nottingham Castle's most famous ghost story. As Edward III had Mortimer arrested in October 1330 in the royal chambers, the King's mother Isabella screamed in anguish to him, "Bel fitz! Bel fitz! Eiez pitie du gentil Mortimer!" which in translation means:" Fair son! Fair son! Have pity on good Mortimer!" Edward, as Alison Weir points out in her new book, ignored his mother. A number of people claim to have heard the queen's ghostly shrieks over the years, including some American G.I.s, stationed in Nottingham during the last war.

From the Lincolnshire Echo, September 2005:

Alison Weir takes a huge step back in time into the 1300s for her biography of Isabella of France, Edward II's Queen, who has long been portrayed as an evil woman, with playwright Christopher Marlowe calling her "that unnatural Queen, false Isabel", and popular legends speaking of her angry ghost clutching the heart of her murdered husband. But Weir believes it is "her sexual misconduct that has above all made Isabella infamous". She said: "Her reputation rests largely on the prejudices of monkish chroniclers and Victorian historians. If she had not taken a lover, her story would have been very different. An examination of contemporary records reveals that she had many fine qualities, and instead of incurring shame, dishonour and revilement, she might have been seen as a liberator, the saviour who unshackled England from a weak and vicious monarch and helped to put a strong king on its throne."

Weir therefore wrote this first full-length biography of Isabella in a scholarly context in which women's personal lives do not dictate wholly the way we interpret their roles in the public world.

From the Lincolnshire Free Press, October 2005:

An enjoyable evening was had by all when historian Alison Weir visited a Spalding store to sign copies of her new book. During the evening at Bookmark, Alison talked about her new biography, Isabella, She-Wolf of France, Queen of England, and answered questions from the audience.

Store owner Christine Hanson sa|d it was a thoroughly enjoyable session. She added: "This was Alison's first visit here. It was a really nice, informative evening."

In the dramatic biography Alison examines the reputation that Isabella has held through history and questions whether it is justified or whether as a French princess she was a pawn in the politics of the day. The book looks at her life from when she came to England, aged 12, through her turbulent marriage to Edward II, his murder, and her eventual residence at Castle Rising, Norfolk.

From The Sunday Times, March 2003

Review by Alison Weir

The deposition of Edward II by his Queen, Isabella of France, and her lover, Roger Mortimer, was one of the most sensational episodes in English medieval history. Edward of Caernarvon, who succeeded to the throne on the death of the formidable Edward I in 1307, had little interest in ruling England. He desired to share sovereign power with Piers Gaveston, the Gascon knight's son to whom he was pleased to refer as his brother. Edward was inept and given to such unmajestic pleasures as thatching, roofing and consorting with actors, while Gaveston was arrogant and unforgivably rude to the barons who, with justification, considered that they, not this upstart, should be the King's natural counsellors. Whether or not the relationship between Edward and Gaveston was homosexual, as was asserted by many contemporaries, is still a matter of debate, but it outraged the barons, who seized Gaveston and beheaded him in 1312.

Edward's Queen, the beautiful Isabella of France, who was no more than twelve when they married in 1308, was as yet too young to register more than token protests against Gaveston, and after his death, she bore Edward four children and lived with him in apparent harmony for many years. But the murder of the favourite did little to repair Edward's relations with his barons, and after England's disastrous defeat at Bannockburn in 1314, he was obliged to live under their tutelage. Isabella helped to maintain peace by intervening from time to time between her husband and the lords.

After 1318, however, Edward became in thrall to a new favourite. Hugh le Despenser, who was more rapacious and ruthless by far than Gaveston. This time, it was not only the barons, but also the Queen, who were hostile to the favourite. Again, it is not known for certain whether the relationship between the King and Despenser was homosexual, but it is possible that the latter personally - or even sexually - humiliated Isabella. He was certainly the cause, in 1324, of her being deprived of her liberty, her estates, her French servants and her children, all of which earned him the Queen's undying hatred ando finally alienated her from her husband.

In 1325 Isabella went to France on a diplomatic mission to her brother, King Charles IV. When this was satisfactorily completed, and her eldest son, another Edward, had crossed the sea to pay homage in his father's stead for lands held by England in France, she refused to return home, despite King Edward's commands and pleas. Instead, she took a lover, Roger Mortimer, Lord of Wigmore, an exile who had defied Edward and Despenser and been imprisoned in the Tower, whence he had daringly escaped in 1323. With Mortimer, Isabella plotted her revenge on Despenser, and in September 1326, with military aid from the Count of Hainault, they led a successful invasion of England, which resulted in Despenser's horrific execution and Edward's forced abdication in favour of his fourteen-year-old son, who was crowned Edward III on 1 February, 1327.

During his minority, Mortimer and Isabella ruled England. They were pragmatic, rapacious and tyrannical, and it was not long before they became unpopular and feared. According to the official account, which until recently was virtually undisputed, Edward II died a prisoner in Berkeley Castle in September 1327; some chroniclers asserted that he had been murdered with a red-hot spit thrust into his bowels, which presumably contemporiaries would have seen as a suitable end for one who was belived guilty of homosexual congress.

In 1330 a palace revolution engineered by the young King and his supporters resulted in the overthrow of Mortimer and Isabella's regime. Mortimer was executed for treason, but Isabella was spared, and spent her remaining 28 years in honourable and luxurious retirement.

This dramatic saga is the subject of two riveting books, Isabella and the Strange Death of Edward II by Paul Doherty, and The Greatest Traitor: A Life of Sir Roger Mortimer by lan Mortimer (a very distant relation). Doherty"s book is partially based on his magnificent 1977 thesis on Isabella of France; Mortimer's is the first independent study of Roger Mortimer, and brilliantly researched it is. The main thrust of both books is the mysterious fate of Edward II, and each is structured in the same way: the first part is a narrative history up until 1327, then comes an examination of the events leading to Edward II"s supposed murder. Each writer then cleverly keeps the reader in the dark until the final chapter, which in each case is an examination of the evidence for Edward's survival. This ploy ensures that both books are compelling page-turners, because enough clues and questions have been planted in the main texts to leave the reader thirsty for a conclusion.

As to those conclusions, which in each case are quite different, I have no intention of giving either away. The pivotal evidence is a letter sent to Edward III after 1330 by one Manuele Fieschi, which claims that Edward II had escaped from Berkeley and settled as a hermit in Lombardy. Both Doherty and Mortimer offer brilliant deconstructions of this highly controversial letter, with remarkably disparate results. The issue is further complicated by the emergence in 1338 of a pretender, William of Wales, who claimed to be the deposed Edward II. There were certainly doubts in Edward III's mind as to whether his father had been murdered, as he was anxious that this man be brought before him; furthermore, William of Wales was not executed as an imposter, as one would have expected. Doherty and Mortimer have different views about this pretender.

Despite his excellent summing up of Isabella's career, I would have liked Doherty to have included more of the detail and revisionist arguments that made his thesis so interesting and convincing; without them, Isabella remains subsidiary to the main thrust of his book. Doherty asserts that it was she who was the driving force in the relationship with Mortimer and the power behind the throne, but I have to agree with lan Mortimer that it was her lover.

lan Mortimer succeeds in bringing Roger Mortimer to life as never before, and his set pieces are brilliant - I have never read such good and clear accounts of the Despenser war of 1321-2 and Roger's escape from the Tower in 1323. However, I did feel that the author was rather over-sympathetic to his subject, who was undoubtedly much more rapacious than he claims.

These, however, are minor criticisms. Both books are an important contribution to the literature on the period, and will certainly help to clarify and further the debate on the fate of Edward II. No one reading them could be left in any doubt that the hitherto accepted tale of Edward's murder at Berkeley is open to question.

(Alison Weir is currently researching a biography of Isabella of France, for publication in 2005.)

EDWARD II – ENGLAND`S WORST MONARCH?

Alison Weir's pitch for a monarchy debate. George IV won!

Of all the bad monarchs who have ruled in the British Isles, Edward II has to have been the worst. Unlike George IV, who merely reigned, this walking disaster actually ruled, with devastating effects. Born in 1284, the son of Edward I, one of England`s greatest medieval kings, he grew up with everything going for him and ascended the throne in 1307 to `the greatest rejoicing`. He was young, good looking, and had the common touch. The chroniclers of the day praised him to the skies: `God has bestowed every gift on him, and made him equal to, or indeed, more excellent, than other kings.`

`What high hopes he had raised as Prince of Wales,` observed Edward`s monastic biographer ominously, for the people were soon to be bitterly disillusioned, and `all hopes vanished when the Prince became king`. His martial father, who had had a great vision of a united Britain, had died before he could conquer Scotland and left instructions that his bones be carried at the head of his successor`s army until that conquest was complete. But Edward II was not interested, and immediately abandoned the struggle. His first act as king was to summon home his favourite, Piers Gaveston, a young man whose influence on him had so disturbed Edward I that he had exiled Gaveston more than once. Edward II now gave Piers a royal earldom and a vast income, and soon the favourite was entrenched at court, where `the King did him great reverence and worshipped him`. Soon, Gaveston was the most important man in the realm after his adoring master. Unsurprisingly, the great nobles loathed him, because he lorded it over them like a second king, to whom all were subject and none equal. It was the traditional right of a military aristocracy to be the King`s advisers, but here was this upstart usurping their privilege – not to be borne! And it was not only the magnates who were furious; `all of the land hated him too, and his name was reviled far and wide`.

There were rumours, probably well-founded, that Edward and Gaveston were lovers, but it was not this that outraged the lords so much as the fact that Edward was treating the unworthy Gaveston as if he were his brother in kingship and permitting him to exercise lucrative patronage; he even allowed him to make all the arrangements for the coronation. And when Edward made a dazzling marriage with Isabella, the beautiful daughter of the powerful French King, the bride was shunted aside and neglected as her husband fawned upon Gaveston. Soon, the young Isabella also discovered that Edward was quite unlike what she, and everyone else, expected a king to be.

Because, for a start, Edward II didn`t even want to be king. He wasn`t interested in ruling England, and he cared nothing for his royal duties. On the contrary, he was quite content to share his power with Gaveston, and use the perks of kingship to enrich his friend and enjoy himself. He didn`t always conduct himself like a king, and in no way did he personify contemporary ideals of kingship. Unlike his father, he was ineffectual when it came to imposing his will on his volatile barons, and consequently he forfeited their respect.

Edward had the oddest tastes for a monarch. Traditionally, medieval kings were war leaders and aristocrats, and their interests reflected this. They enjoyed hunting, tournaments and fighting. Edward II hated tournaments, and never went to war unless necessity drove him to it, which exasperated his barons beyond measure.

The barons were even more horrified by their sovereign`s leisure pursuits, which included digging ditches with labourers, thatching roofs, trimming hedges, plastering walls, working with metals, shoeing horses, driving carts `and other trivial occupations unworthy of a king`s son`. The tragedy was that Edward had the potential to be a great king: `If only he had expended on arms the time he gave to rustic pursuits, he would have raised England aloft, and his name would have resounded throughout the land.`

Instead, the King wasted his abilities in constant wrangling with his lords over Gaveston to the point of civil war. He could be wayward, petulant, vindictive and viciously cruel when sufficiently provoked. He was lazy, weak, lacking in judgement and intuition. His better qualities were insufficient to command the respect of his people, while his faults looked set to undermine the very throne itself.

Parliament`s condemnation of Edward`s rule was shattering. He was accused of corruption, extortion, failing to prosecute the war with Scotland and dismembering the Crown lands in order to give them to Gaveston. Things got so bad that in 1312 a coalition of magnates effected a coup and executed the favourite, a deed for which Edward would never forgive them. Indeed, his wings well and truly clipped for the present, he would bide his time until he could exact a terrible vengeance.

In 1314, bestirred at last to move against Robert the Bruce, who had had himself crowned King of Scots, Edward finally marched north at the head of a great army. The Brice druly observed that he feared Edward I`s bones more than his living son. His words were prophetic, because at Bannockburn he inflicted the most humiliating defeat on the English King, a defeat that would pave the way for years of Scottish terrorism in the north and the historic Declaration of Arbroath of 1321, which established Scotland`s independence. It was, mourned the chroniclers, a `day of loss and shame` that should be expunged from the calendar. It was no wonder the King couldn`t win a battle, people said, because `he spent his time in idling, ditching and other improper occupations`. The defeat led to further clashes between Edward and his barons, with the latter determined to impose constraints on him, and while the conflict raged, the country suffered years of famine.

By 1320, Edward had found new favourites, the vicious Despensers, father and son, who were far more ruthless and `fired by greed` that Gaveston had ever been. With their support, the King finally moved against his barons, executing and imprisoning their leaders and savagely instigating not just a judicial bloodbath, but a veritable reign of terror. Unsurprisingly, the Despensers were now hated by the whole realm, and also by the Queen. But, undeterred, Edward from now on `truly governed his country with great cruelty and injustice`, allowing his favourites brutally to intimidate and extort at will. Having finally alienated the long-suffering Isabella, the King happily complied when the Despensers systematically inveigled him into depriving her of her servants, her income, her children and her liberty.

Incensed and in fear of her life, Isabella refused to return home after being sent to France to help negotiate a peace. She had with her her eldest son, Prince Edward, a most valuable political pawn, and with the support of Roger Mortimer and other disaffected barons, she returned to England at the head of an army and swept all before her. The Despensers were executed as traitors, and in January 1327, Edward II was forced to abdicate, and his son was crowned king as Edward III, with the whole country rejoicing. Soon afterwards, lurid tales of the deposed Edward`s gruesome murder at Berkeley Castle began to circulate, but these were probably mere propaganda; indeed, mystery surrounds the King`s fate, and there is some evidence that he was not murdered at all.

Be that as it may, the removal of Edward II had by 1326 become a political imperative. Never before or since has a British monarch so neglected his responsibilities or abused his power. As was so graphically and truthfully stated in the Articles of Deposition, Edward was incompetent to govern, unwilling to heed good counsel, and more than willing to be governed by evil advisers. He had lost Scotland, Ireland and Gascony; he had plundered the realm and disinherited many of his subjects; he had violated his coronation oath to do justice to all; and he had shown himself incorrigible through his cruelty and weakness and was beyond all hope of amendment.

It can`t get much worse than that, can it? And that is why I hope that you will agree that Edward II was Britain`s worst monarch.