Books

Lancaster and York: The Wars of the Roses/The Wars of the Roses (1995)

8 September 2014: Nineteen years after it was first published, this book reached no. 1 in the Wall Street Journal non-fiction e-books bestseller list, and no. 3 in Amazon.com's Kindle Select 25!

"Weir does a masterful job of leading the layman through the entwined family trees of England and the many usurpers to the throne... [She] has perfected the art of bringing history to life." (Chicago Tribune)

"Popular history in the best sense... Illuminating asides make Miss Weir`s history a joy to read. So do her little gems of scholarship." (The Economist)

"A spellbinding chronicle... Weir`s dark, glorious pageant restores the personal dimension to an oft-told tale." (Publishers Weekly)

"A gripping account." (The Independent on Sunday)

"This is very readable, populism of the best kind." (The Times)

"A magnificent history." (The Boston Globe)

"Alison Weir gives this remarkable period of history a human touch... the reader gains a fascinating insight." (Lancashire Evening Post, Pick of the Week; Metro)

"Alison Weir's immensely readable book makes sense of a complex period in English history... She brings alive a period that most people know only through the propagandist writings of William Shakespeare, and her grasp not only of the politics of fifteenth-century England but of the lives of the protagonists makes this book a valuable addition to the growing volume of work on one of the most fascinating periods of English history." (Yorkshire Evening Press)

"A perfectly focused and beautifully unfolded account." (Booklist, starred review)

"Stimulating, well-written, entertaining." (Library Journal)

"Powerful and elegant... A complicated story brilliantly told." (Kirkus Reviews)

"Her detail is immaculate... She has read more widely in contemporary texts than recent historians... She manages her material well, but it is her set-piece stories that impress; many have never been told so well... This is epic." (Teaching History)

"Alison Weir has taken some splendid leading characters, a large cast, the shifting alliances and fortunes of the Wars of the Roses, and turned them into an exhilarating book... Alison Weir writes compellingly. Her art is such that the reader is swept along by the story, scarcely noticing how very complicated that story is." (The Literary Review)

"Surrey abounds with excellent writers, but amongst the best, for those with a thirst for history, has to be Alison Weir. Here we have an in-depth account which reveals details like no history teacher ever taught... A fascinating insight into the past, a book that cannot fail to please historians who also enjoy a very good story. I can highly recommend it." (Surrey County Council Magazine)

"Alison Weir guides the reader through the fog quite faultlessly. Lancaster and York illustrates Weir's ability to marshal a mass of information and create from it a gripping narrative, and her knack of using historical sources to evoke memorable characters." (Waterstone's History Guide, 2003)

"Alison Weir combines a radical new look at accepted historical truths with a compulsive readability." (The Mail, Cleveland)

"Powerful and elegant... A complicated story brilliantly told." (Kirkus Reviews)

"All this is brought dramatically to life... [Weir] writes well and is skilled at delineating the many memorable characters of the age... Narrative coherence is the chief strength of [her] book... It's a tribute to her skill that she leaves you wanting more." (The Plain Dealer, Cleveland)

"An exciting and fast-moving account of the human side of the Wars of the Roses... a refreshing look at the conflict from the viewpoints of those who took part... A fascinating and worthwhile account that presents an extremely complicated subject in an accessible and interesting way. Alison Weir writes in a clear and focused style, and her enthusiasm for her subject shines through to the reader." (Suite 101)

Above: Preliminary U.K. and U.S. paperback jackets.

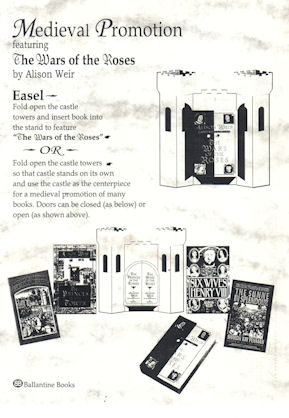

American display stand, 1995

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, U.K., 2010

(The Battle of Bosworth, by Graham Turner)

Why did you write The Wars of the Roses?

Originally, I had planned a book on the downfall of the royal House of Plantagenet, a very ambitious project that spanned the period 1399 to 1563. As I researched, it, I found I was amassing a lot of material on the Princes in the Tower. Up to then, I was of the opinion that there was little more to be said on that subject, but it soon became clear that there was plenty, so I proposed a book on the Princes, and my publishers agreed enthusiastically. In that book, which was published in 1992, I told the story of the second War of the Roses, between the royal Houses of York and Tudor. There was, of course, another story, that of the earlier conflict between the Houses of Lancaster and York, so I decided to write it as a prequel.

Was it a difficult book to write?

Yes, because there are so many warring nobles and families, and many have similar names. Also, military history is not my main interest - it's the people who fascinate me, so I saw my chief challenge as bringing them vividly to life so that the subject would not be too confusing for the reader.

Are there good sources for the period?

Yes, many of them. Some, such as the Paston Letters, paint a very evocative picture of life at that time. Others can be annoyingly vague, and of course there are gaps in our knowledge. But look at the bibliography - there is a lot of good material. There have been great archaeological discoveries too, in regard to the battles - some of them since the book was written.

Did you come to enjoy writing about the battles?

Contrary to expectations, I did. They are very dramatic and often tragic events. One is constantly struck by the soldiers' capacity for survival. One or two battles were on a horrific scale, such as Towton in 1461. In other cases, it wasn't so much the battlefield that witnessed the carnage as the rout of the vanquished afterwards.

What did you enjoy most about writing the book?

The people! They are some of the most charismatic characters in history - pious Henry VI, his 'strong-laboured' queen, Margaret of Anjou, that licentious charmer and ruthless operator, Edward IV, Henry V, the chilling victor of Agincourt, the megalomanic Richard II, the sadistic John Tiptoft... I could go on!

I was also interested in how a dynasty can destroy itself. That was the original theme of my project. There was to have been a third book in the trilogy, a sequel to the other two called The Last Plantagenets, showing how the Tudors systematically eliminated their Yorkist rivals. I've done a huge amount of research, but as yet no publisher has commissioned that one. Of course, the characters are not so well known, but it's a grim and bloody tale of plots, treason and executions. One day, perhaps!

Would you ever like to revisit the fifteenth century?

I hope to do so for two forthcoming projects, one of which is a history of England's medieval queens, whom I have researched extensively, and the other is a novel based on the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower.

Have you changed your view that Richard III was guilty of their murder?

I have had no reason to, but I remain objective and open to persuasion.

Is this your favourite historical period?

It comes a close second to the Tudor period. I've been fascinated by the House of York since my mother gave me a book on 'Jane' Shore, Edward IV's mistress, when I was a teenager. I'm a passionate medievalist, but a lot of my research has never been published.

Who is your favourite historical personage?

I can never decide between Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII, Elizabeth I and Eleanor of Aquitaine! But I probably wouldn't want to invite them to dinner all at once.

Of all your books, which is your favourite?

The latest one! Always!

INTERVIEW WITH ALISON WEIR, U.S.A., 2010

(The battles of Barnet and Tewkesbury)

1. In general terms, what are the ingredients that make the era 1399-1485 of the Houses of Lancaster and York so fascinating and exciting to anyone interested in Britain's history? (It has, after all, provided everyone from Shakespeare to you with a rich focus of study.)

It is the power conflict that fascinates, the often bloody battle between right and might for supremacy, played out between kings, queens and nobles. But who had the right? It's a matter that has been endlessly and heatedly debated, from the fifteenth century to the present day. The period began with a usurpation, which put an end to the rightful Plantagenet line, and it ended with one of the most dramatic battles in history. In between, there were plots, intrigues, military clashes, love affairs, betrayals and murders. There were a lot of sinister operators in this period, and several enduring mysteries, not the least of which is the fate of the Princes in the Tower. It's also an era that epitomises the high Middle Ages, with chivalrous knights braving all in tournaments, ladies in steeple head-dresses, towering castles and colourful pageantry, all of which appeals to the romantic in us all. I think that's enough to justify the interest - as I often say of history, you couldn't make it up!

2. How should we view Shakespeare's plays concerning the era - as historical fact or theatrical romps?

Shakespeare's plays were based on Tudor historical sources such as the chronicles of Raphael Holinshed, which were limited in scope and source material, and biased in favour of the ruling dynasty. In order to underline the peace and stability they had brought to England, the Tudors and their advisers liked to present the preceding Wars of the Roses between Lancaster and York as a long and bloody civil war. Bloody it was, indeed, but the bloodshed was isolated and not prolonged. In fact, there were only thirteen weeks of fighting in thirty-two years, and the architecture and literature of the time do not reflect a preoccupation with war. In fact, the battles were collectively known as "the Cousins' wars", because they affected primarily the rival claimants. This mythical view of the conflict was well established by Shakespeare's time, and it is this version that he presents in his plays. Dramatic licence aside, they are based on fact, but they also reflect the political prejudices of his age.

3. How critical was Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Wydville as a cause for the civil wars known as the Wars of the Roses?

Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville was not a cause of the Wars of the Roses, which had begun nine years before it was contracted, but it certainly escalated the conflict. Edward's chief supporter and mainstay was the hugely powerful Earl of Warwick, "the Kingmaker", and when the King's secret marriage - made for lust - to Elizabeth was made public in 1464, Warwick was not only as scandalised as the rest of the nobility, but he was discountenanced too, because he had been negotiating for a French royal marriage for England's political advantage. In his eyes, Elizabeth, the impoverished widow of a Lancastrian knight, was no match for his master. Worse still, Elizabeth brought to the marriage a horde of ambitious, grasping relations, who swiftly began to undermine Warwick's influence while enriching and advancing themselves. Soon, there were two factions at court, and within five years, Warwick had broken with Edward and allied himself to the King's treacherous brother, George, Duke of Clarence. Having allied themselves with the Lancastrians, they invaded England in 1470, causing Edward IV to flee abroad, and set the ailing Henry VI on the throne again, as a puppet king. When Edward raised an army and reclaimed his kingdom the following year, Warwick was killed at the Battle of Barnet. But the Lancastrian threat remained to be dealt with. Soon afterwards, Edward routed the forces of Henry's queen, Margaret of Anjou, at Tewkesbury in a crushing defeat that put an end, for the time being, to the dynastic hopes of the red rose. Later that month, Henry VI was murdered in the Tower of London. That brutal act brought to an end the first War of the Roses. Had Edward IV not married Elizabeth Wydeville and alienated Warwick, that war might well have ended a decade earlier.

4. What in your view is the key evidence that compels us to believe that Richard III was responsible for the deaths of the Princes in the Tower?

The strongest evidence is that the Princes disappeared in the summer of 1483, when they were securely held in the Tower, in Richard's custody, guarded by his trusty supporters, and at a time when their removal would have been very much in his interests. Furthermore, when it would have been crucially to his advantage to do so, in order to counteract the rumours of murder that were fatally undermining his throne and his reputation, Richard maintained silence on the subject of the Princes. Gradually, some details of their fate became known. Sir Thomas More certainly had inside knowledge obtained from those in a position to know: his description of the burial place of the Princes tallies exactly with where the bones of two children were found nearly two centuries later. The evidence for their murder is fragmentary and circumstantial, but, put together, it is strong.

5. Did his plan to secure his throne by doing away with the Princes backfire?

Yes, it did, because while most people in that age had little problem with men dying violently on the field of battle, and political murders were commonplace, "the shedding of infants' blood" shocked Richard's cotemporaries as much as it does us today. Rumours that he had had the Princes killed were rife in England only weeks after their disappearance, and had spread to France by the following year. Henry Tudor, in exile, certainly believed that the Princes were dead, and publicly vowed to marry their sister, Elizabeth of York, and claim the throne in her name. The increasingly widespread belief in Richard's guilt, coming on top of his tyrannical rule as Lord Protector, undermined his security and his throne, and gave his enemies a pretext to move against him or betray him. And in 1485, Henry Tudor invaded England. The rest, as they say, is history!

6. You say in The Princes in the Tower that the murder of the Princes may be viewed in its wider context as a single event that dramatically changed the course of history: how?

Rumours of the murder of the Princes, which Richard never counteracted, laid him open to treasonable plots and conspiracies, such as that by Henry Tudor, whose army defeated Richard's at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. Richard was killed as he made a last, desperate charge, and his death brought to an end the rule of the Plantagenets, who had governed England for 331 years; it also paved the way for the Tudors, who brought revolutionary change to England. Thus far the murder of the Princes could be said to have changed the course of history. There was an indirect effect, too. Richard III left behind several indirect heirs with a claim to the throne; their presence would be a continual threat to the Tudors for the next eighty years, and contributed in no small way towards the ruthlessness with which the insecure new dynasty was to govern.

DAUGHTERS OF YORK

The Daughters of Edward IV: Elizabeth of York and her Sisters

(Proposal for an unpublished book)

The story of the daughters of Edward IV spans the period between the Wars of the Roses and the reigns of Henry VII and Henry VIII. It is the poignant and sometimes tragic story of seven sisters whose lives were inextricably caught in the turmoil of civil war and the establishing of the usurping Tudor dynasty.

Two of the sisters died young, Margaret in infancy in 1472, and Mary at fourteen in 1482. The youngest, Bridget, who may have been mentally retarded, became a nun at Dartford and died before 1517 two decades before the dissolution of that house by her nephew, Henry VIII.

The eldest daughter, Elizabeth of York, was the most important historically. On the rumoured murder of her brothers, the Princes in the Tower, she became, in the eyes of many, the Yorkist heiress to the throne. To consolidate his position after overthrowing the last Yorkist King, her uncle, Richard III, at the Battle of Bosworth, Henry VII married Elizabeth in 1486, at which time she was almost certainly pregnant by him. Their marriage was outwardly happy, but Elizabeth`s role as Queen Consort was overshadowed by her powerful mother-in-law, the Lady Margaret Beaufort, who ruled the court as virtual Queen Mother. Elizabeth bore her husband eight children, including the future Henry VIII, before dying in childbed in 1503. She is an enigmatic figure, who had perhaps enjoyed a brief affair with her uncle, Richard III (who certainly wanted to marry her), and this may have been one reason why her husband, Henry VII, kept her under constraint. Yet contemporaries, including Sir Thomas More, had nothing but good to say of her.

Elizabeth`s next sister was Cecily (1469-1507), who married firstly Viscount Welles, and secondly, reputedly, a commoner called Thomas Kyme. Cecily was close to Queen Elizabeth. Their younger sister, Anne, married Thomas Howard, son of the Earl of Surrey. The Howards had fought for Richard III, but by the time of the marriage were well on the way towards rehabilitation and becoming one of the premier dynasties of Tudor England. But Anne`s four children all died in infancy. She died around 1512. Her husband later became the 4th Duke of Norfolk and one of Henry VIII`s most prominent courtiers.

The second-youngest sister (Bridget, the nun, was the last to be born) was Katherine of York. She married William Courtenay, later Earl of Devon, who was imprisoned after rebelling against Henry VII. Queen Elizabeth was powerless to do anything to ameliorate the lot of her sister and her husband, and it was not until the accession of Henry VIII in 1509 that Courtenay was released. Sadly, he died only two years later. Katherine died in 1527. Fortunately, she did not live to see her son, Henry, Marquess of Exeter, executed by Henry VIII for being too near in blood to the throne.

These sisters lived during a magnificent yet dangerous period of English history, and their Yorkist blood would have rendered them a serious threat to the Tudor dynasty, but for the fact that they were women and therefore not considered serious contenders for the throne. But for their male children, it was a very different story...

THE THIRD BOOK IN THE TRILOGY

My book Lancaster and York does not stand alone. There is a sequel, The Princes in the Tower, and the trilogy was to have been completed by a third book, The Last Plantagenets, but although I have pitched the idea twice to my publishers, they have preferred other suggested titles. Here is the original proposal, from 1990, which shows how the Tudors systematically eliminated their Plantagenet rivals.

THE LAST PLANTAGENETS

INTRODUCTION

The Tudors were an usurping dynasty. They came from bastard stock and their pedigree gave them no legal title to the crown of England. But the founder of the dynasty, Henry VII, defeated the last Plantagenet king, Richard III, of the House of York, at the Battle of Bosworth in 1485, and claimed the throne by right of conquest. There were at that time at least twenty members of the royal House of Plantagenet still living, all of them with a better claim to the throne than Henry VII. Several were women. Henry married the Yorkist heiress Elizabeth of York (daughter of Edward IV and niece of Richard III) in 1486, and thereby strengthened his claim, but he made it clear that he considered the crown to have been won by right of conquest and not by marriage. As for the other female Plantagenets, England had not experienced a woman's rule since the brief and disastrous reign of the Empress Matilda in the twelfth century, and no one seriously contemplated standing up for their rights to sovereignty. Moreover, there were several serious male claimants to the throne whose lineage took precedence, and it was they who posed the most serious threat to the usurper.

Henry VII was acutely aware of the insecurity of his position. Not only did he have to contend with dynastic rivals, but also with pretenders to the throne, who claimed to be either one of the Princes in the Tower (the brothers of Elizabeth of York, who had probably been secretly disposed of by Richard III), or Richard's nephew, the Earl of Warwick. The fate of the Princes in the Tower was the key factor influencing the change of dynasty: had the elder, Edward V, succeeded his father as undisputed king in 1483, Bosworth would never have been fought and the Tudors would have remained obscure scions of the House of Lancaster. Instead Edward V was deposed by his uncle, Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who became Richard III, and was afterwards disposed of, with his brother, Richard, Duke of York, in the Tower of London.

There is no hard evidence that Richard III, the last Plantagenet King, murdered his nephews, although the circumstantial evidence is overwhelmingly in favour of this theory. It is equally clear that Henry VII had no clear idea of what had become of the Princes, so secret had been their fate. From the time of Richard Ill's accession, rumours of their deaths abounded, as occasionally did rumours of their survival, which persisted into the reign of Henry VII. Neither Richard nor Henry issued any definitive statement as to what had become of them. In such a political climate, pretenders flourished, and here again there are unsolved mysteries.

Henry VII's most serious rival for the throne at the beginning of his reign was John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, Richard Ill's nephew and designated heir. In 1487 Lincoln supported a rebellion in favour of a pretender Lambert Simnel, but was defeated and killed by Henry VII's army at the Battle of Stoke Field, the last battle of the Wars of the Roses. Another serious threat to Henry's security was-the Earl of Warwick, another nephew of Richard III, whose claim to the throne was superior to Henry's. Warwick, however, was a simpleton, and had spent most of his life in captivity in the Tower. In 1499, he seems to have been lured into a conspiracy with the pretender Perkin Warbeck by an 'agent provocateur', which gave Henry VII the excuse he needed to execute both men.

Thus the King set a pattern for the future: any member of the old royal House with pretensions to the throne would be ruthlessly eliminated. It was a policy that would be implemented by the Tudors for no less than eighty-five years, spanning the reigns of Henry VII, Henry VIII, Edward VI, Mary I and Elizabeth I.

Of course, not all the surviving Plantagenets and their descendants went to the block. Some gained high office and served the new dynasty, to whose sovereigns they were quite nearly related, although these were the souls who trod a perilous path. A few retired to their country estates, shunning public life; they, for the most part, were left unmolested. Many of the women were married off to 'safe' husbands, but this failed to prevent some of their children, and grandchildren, from reviving their claims to the throne - usually with disastrous consequences. Of the women, Margaret Pole, Warwick's sister, fared the worst of all: when she was sixty-seven, Henry VIII sent her to the scaffold on a trumped up charge of treason, believing that she coveted his throne, and the old lady was callously butchered by an inept executioner.

"The Last Plantagenets" tells the story of these unfortunate people, and relates the fortunes of the various families concerned, the intrigues in which they were involved, and the terrible fate suffered by those whose annihilation was necessary for the security of the new dynasty. The book spans the period 1483 to 1570, and is set against the splendours of the Tudor court, the grim surroundings of the Tower of London, and the country seats of the nobility.

This was an age peopled with colourful and fascinating characters: kings, queens, churchmen, power-hungry magnates, saints, whores and scholars. The Tudors themselves stand out as dynamic and charismatic characters; only slightly less so were the subjects of this book - the last Plantagenets. Mystery and intrigue are the backbone of their story, from the disappearance of the Princes in the Tower to the enigmas of the pretenders and the truth behind the alleged treason plots of the Yorkist faction. There are few conclusive answers to these questions, but this book assesses the evidence and offers the likeliest theories.

PROLOGUE: LANCASTER AND YORK AND THE WARS OF THE ROSES

(L-R: Executions after the Battle of Tewkesbury; Edward IV; George, Duke of Clarence)

The prologue covers the period from 1397 to 1483. The first half describes the origins and course of the English civil wars of the fifteenth century and the struggle for the crown between two rival royal dynasties, the Houses of Lancaster and York, assessing the relevance of the Wars of the Roses to the history of the period, and showing how both Yorkist and Tudor propaganda distorted the popular conception of them. Background information about the important members of the Houses of Lancaster and York is provided, and emphasis placed upon the rise of the Yorkists. For although Henry Tudor claimed to be the Lancastrian claimant to the throne, the true Lancastrian line had died out in 1471 when the first phase of the Wars of the Roses ended, and the dynastic struggles of the period 1483-1487, the second phase of the Wars, were in fact a contest between Yorkists and Tudors. The rival claims to the throne are examined and their validity clarified, a task fraught with difficulty. It was not clear then, and is hardly any clearer now, who had the better right to the throne.

The second half of the Prologue includes a brief account of the reign and achievements of Edward IV, the first of the Yorkist kings. Attention is focussed on his character, his amorous exploits and his scandalous marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville, which had calamitous long-term effects upon the Yorkist dynasty and adversely affected both the King's brothers, George, Duke of Clarence, and Richard, Duke of Gloucester.

The careers of both Clarence and Gloucester during Edward's reign are described, with an account of the treason and execution (probably by drowning in a butt of Malmsey wine) of Clarence in 1478. He left two young children, Edward, Earl of Warwick, and Margaret Plantagenet.

The character of the Duke of Gloucester is examined, in the light of what was known about him before the death of Edward IV; a certain ruthlessness was already apparent. There were allegations that Gloucester was partly responsible for the murder in the Tower of the deposed Lancastrian king, Henry VI, in 1471. His marriage to the daughter of Warwick the Kingmaker and his political role as Lord of the North are also described.

The aim of the Prologue is to provide concise background information to a very complex subject, and to set the scene for the momentous events that happened after the death of Edward IV in April 1483.

CHAPTER ONE: OCCUPATION

(L-R: Elizabeth Wydeville; Richard III; Richard is offered the crown)

This chapter opens with the accession of the twelve-year-old Edward V in April 1483 and a description of the power struggles between the magnates for control of the royal Council during the young King's minority. The life and character of Edward V are chronicled, and it becomes clear that he was entirely under the influence of his mother, Elizabeth Wydeville, and her unpopular faction. This augured ill for Richard, Duke of Gloucester, who was named Lord Protector of England during the King's minority in a codicil to Edward IV's will, Gloucester had reason to hate and fear the Woodvilles, for they had engineered Clarence's death. Now they were plotting to prevent Gloucester from holding any post of authority during Edward V's minority.

Gloucester, whose power in the north and west of England was vast, had allied himself to the powerful and influential Duke of Buckingham, a descendant of Edward III whose family had originally fought for the House of Lancaster, but who was now tempted by the prospect of preferment and power to join forces with the Yorkists, and with Gloucester in particular. Together, these two dukes executed a sudden and dramatic coup, intercepting the young King on his way to London and his coronation, arresting his Wydeville guardians (who Richard later had executed after a travesty of a trial) and taking control of the government.

When the Queen learned what had taken place, she fled into sanctuary in Westminster Abbey. Gloucester was proclaimed Lord Protector. Shortly afterwards, the boy King was lodged in the royal apartments in the Tower of London, as was customary preceding a coronation, where he was later joined by his brother, Richard, Duke of York, aged nine, who had been taken from sanctuary despite his mother's protests.

There followed the summary beheading without trial of Lord Hastings, a staunch supporter of Edward IV and Edward V. From that time onwards it was obvious to all that Gloucester was aiming for the crown. After Hastings' death, the King and his brother were withdrawn to more secure lodgings within the Tower, and a week later it was announced that the children of Edward IV were bastards because evidence had come to light that Edward IV had been precontracted to another lady, Eleanor Butler, at the time of his marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville, Under canon and common law this invalidated the second union and bastardised any children born of it. Since the young Earl of Warwick, Clarence's son, was allegedly barred from inheriting the throne by the Act of Attainder passed against his father, the crown of England, it was asserted, should rightfully belong to the Duke of Gloucester. Thus came about the accession of Richard III.

This chapter presents a concise account of these events, which were crucial to the fate of the Plantagenet dynasty, and how they aroused horror both at home and abroad. The 'precontract' claim, which probably had no basis in fact, is discussed, as well as Gloucester's motives throughout his nephew's short reign.

CHAPTER TWO: THE SHEDDING OF INFANTS' BLOOD

(L-R: Richard, Duke of York, and Edward V; the Tower of London; the urn in Westminster Abbey)

This chapter looks at the evidence for the fate of Edward V and his brother, the Princes in the Tower, a subject that has given rise to numerous books and heated controversy through five centuries. Here the evidence is collated and presented in chronological order. The sources used are as contemporary to the Princes' disappearance as possible, although relatively few survive, and those that do are often biased. The best sources are the accounts left by Dominic Mancini and the Continuator of the Croyland Chronicle. There is an assessment of the medical evidence relating to bones found in the Tower in 1674 and assumed to be those of the Princes.

The chapter also provides the background to the first months of Richard Ill's reign, and relates how rumours of the fate of the Princes spelt disaster for the King. There is a detailed assessment of Richard's character.

Various theories as to what could have become of the Princes are examined.

CHAPTER THREE: "TREASON! TREASON! TREASON!"

(L-R: Richard III; Margaret Beaufort; Elizabeth of York; Bosworth Battlefield)

The first part of this chapter is about Henry Tudor, the Lancastrian pretender to the throne who emerged in 1483 and his antecedents. The Welsh origins of the Tudor family are traced, and there is an account of the fortunes of Henry's forbears: Henry V's widow, Katherine of Valois, whose affair (or, possibly, secret marriage) with her squire of the wardrobe, Owen Tudor, ended in tragedy; her sons, Edmund, who died young, leaving his child bride pregnant; Jasper, who spent most of his life in exile; and Edmund's wife, Margaret Beaufort, the last legitimate descendant of the liaison between John of Gaunt and Katherine Swynford, through whom Henry Tudor inherited a tenuous claim to the throne. There is an account of the Beaufort family's history, which examines the legality of their exclusion from the succession by Henry IV.

By 1483 Henry Tudor was the only realistic male Lancastrian claimant to the throne. His birth, early life and long exile are described, and the effect on his character evaluated, as well as his claim to the throne.

In the autumn of 1483 the Duke of Buckingham suddenly switched his allegiance from Richard III to the exiled Henry Tudor. The reason for this is obscure, but will be discussed here. There follows an account of the course of Buckingham's rebellion and its outcome and aftermath. On Christmas Day, 1483, Henry Tudor made a solemn vow in Rennes Cathedral to marry Elizabeth of York, Edward IVs eldest daughter. In so doing, he demonstrated that he knew the Princes were dead and that in the eyes of legitimists Elizabeth was her father's heiress. Uniting the claims of Lancaster and York would be a means of bringing peace and stability to England.

However, when Richard Ill's wife, Anne Neville, died in March 1485, amidst rumours that the King had poisoned her, Richard was making plans to marry Elizabeth of York himself, in order to confound Henry Tudor.

The rest of Chapter Three deals with the last months of the reign of Richard III. It ends with an account of the events leading up to the Battle of Bosworth in August 1485, and a description of the battle itself in which Richard was killed, thanks to the treachery of certain nobles. The old legend of Henry being crowned on the battlefield with the King's circlet, which had been found under a hawthorn bush, may have some basis in fact.

CHAPTER FOUR: AN UNKNOWN WELSHMAN

(Henry VII; Elizabeth of York)

This chapter tells the story of the aftermath of Bosworth, showing how Henry VII established the Tudor dynasty on the throne, and why his tenure of that throne was, and remained, insecure. Many assumed that he would marry Elizabeth of York at once, and so strengthen his title. But he did not do so for over four months. Undoubtedly he was at pains to stress the fact that his title to the throne was conferred by right of conquest.

Tudor chroniclers, and later historians, have had nothing but praise for Elizabeth of York. The marriage was a successful one: Henry was a loyal husband and Elizabeth a faithful and dutiful wife.

Henry took other measures to stabilise his position: he had Parliament confirm his title, and did his best to neutralise the surviving members of the House of York, who posed such a dangerous threat to his position. The claim of each individual is assessed in order of importance. Many were women. Strictly speaking, the crown of England should have gone to Elizabeth of York, who was legitimated in Henry's first Parliament, but at that time it was not thought fit that a woman should rule.

Next to Elizabeth of York, those nearest the throne in blood were her four sisters, three of whom the King married to men loyal to himself. The fate of the Yorkist princesses and other females with a claim to the throne is chronicled in the last part of this chapter, in which it will be seen that Queen Elizabeth was not the only one of the Yorkist princesses to pass on her dynastic claims to her children.

Henry VII had an ambivalent attitude towards the subject of the Princes in the Tower, and evidently had no clear idea of what had become of them, which only added to his insecurities. He was so sensitive about the "precontract" of Edward IV that he took stern steps to suppress the story and distort the facts, since it was detrimental to the dynastic title of his queen.

CHAPTER FIVE: THE DARK EARL

(Imaginary portrait of John de la Pole (Frances Quinn, after Titian); the Battle of Stoke)

For the first fourteen years of his reign Henry VII was insecure on his throne. On the death of Richard III, the crown should have passed to his designated heir, his sister's son, John de la Pole, Earl of Lincoln, an able and respected man of twenty-four. Lincoln was therefore Henry VII's most serious rival, although to begin with he offered his allegiance to the new King and came often to court.

This chapter opens with an account of the de la Pole family through the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, relating what is known of Lincoln's life and character, and assessing his potential for kingship. It then explainss why England never had a King John II.

In the winter of 1486/7, there appeared in Ireland a boy said to have been called Lambert Simnel, although this was almost certainly a pseudonym as one of the earliest sources gives his name as John. Mystery surrounds his origins, but what is known is that he first claimed to be Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes in the Tower, and then Edward, Earl of Warwick, Clarence's son, who Henry VII had immured in the Tower. Simnel gained the support of some influential Irish lords, who crowned him Edward VI in Dublin Cathedral and then plotted an invasion of England on his behalf with the aid of Richard Ill's sister, Margaret of York, Duchess of Burgundy. Their aim was to depose Henry VII and set the pretender on the throne. At a late stage, Lincoln suddenly defected to the rebels and fled to Ireland, where his rank and natural authority made him the obvious leader of the rebellion. It is likely, however, that his chief aim was not to set Simnel on the throne but to seize it himself.

This was an ambition Lincoln was destined never to fulfil. The invasion took place but the rebel army was soundly defeated by a superior royal force under the Earl of Oxford at the Battle of Stoke Field, near Newark, in June 1487. Lincoln was killed in the fighting, and Simnel taken prisoner. The King took pity on the lad and set him to work in his kitchens. Later he rose to the rank of King's Falconer.

The Battle of Stoke was just as decisive a victory as Bosworth for Henry Tudor: to him and his contemporaries it appeared that God, giving him victory over his enemies, had spoken decisively in confirming his right to the throne. Stoke also taught any would-be pretenders that victory would not easily be achieved. For this reason, it was the last battle in the Wars of the Roses.

CHAPTER SIX: "RICHARD IV"

(L-R: Perkin Warbeck. Edward, Earl of Warwick; Margaret Plantagenet)

No sooner had John de la Pole been eliminated than there arrived on the scene yet another pretender to the throne. With the mystery of the Princes still unsolved, there were several pretenders in Henry VII's reign, yet none posed so dangerous a threat as Perkin Warbeck. He claimed he was Richard, Duke of York, the younger of the Princes in the Tower, and as such he received staunch support from the Duchess of Burgundy, the King of France and the King of Scots, who gave him his cousin. Lady Katherine Gordon, as a bride. Warbeck's origins, like Simnel's, are shrouded in mystery, and there is a slight possibility that he was a Yorkist bastard. Whatever the truth, he was a thorn in Henry VII's side for years until the King finally caught him in 1497. Even then Henry was lenient, allowing Warwick to live at court (but not to leave it) and treating him and his wife with courtesy. But a year later the rash young man was caught trying to escape, and was then sent to a harsher confinement in the Tower.

The Earl of Warwick was then a state prisoner in the Tower, having been kept in solitary confinement for fourteen years. This chapter includes an account of his life during this period, and an assessment of his mental capacity, for it has often been alleged that he was a simpleton. Yet this son of the executed Duke of Clarence was undoubtedly England's rightful king. The attainder against his father only applied to the lands inherited by, and conferred upon Clarence, not to the right of his son to the throne.

Richard III had deliberately passed over Warwick's claim when it came to naming an heir after the death of his son in 1484, because he knew very well that the boy had a better right to the throne than he did. It was for this reason that he designated Lincoln his heir. Hence Clarence's attainder was presented ever after as a bar to Warwick's accession, a fiction it suited Henry VII very well to maintain.

Henry treated Warwick shabbily, keeping him closely confined from the age of ten. In 1499 he took the opportunity of getting rid of him for good. In that year, negotiations for the marriage of Henry's eldest son, Arthur, Prince of Wales, to Katharine of Aragon, were nearing completion. This was an alliance particularly dear to the King's heart since it secured foreign recognition of his dynasty and helped to bring England to the forefront of international politics. But Katherine's father, King Ferdinand of Aragon, was reluctant to proceed with the marriage while "any doubtful drop of royal blood" remained to challenge the Tudor throne.

What happened next is mysterious. It seems that Warbeck was allowed access to Warwick within the Tower; soon afterwards, both were charged with having conspired to escape from prison and to blow up the gunpowder store in the fortress, thereby causing considerable damage. The circumstances of this plot strongly suggest the involvement of an agent provocateur, for the outcome was that both Warbeck and Warwick were conveniently executed, thus ridding Henry VII of two very real threats to his throne, and preserving the precious Spanish alliance. Even Katherine of Aragon, in later years, would say her marriage to Arthur was doomed (he died after six months) because it was "made in blood".

Chapter Six ends by chronicling the early life of Margaret Plantagenet, Warwick's sister, who, at her brother's death, inherited his claim to the throne; and her marriage to Sir Richard Pole. Her life story will be one of the central themes of the latter part of this book.

CHAPTER SEVEN: SPRING CLEANING AT THE TOWER

(Henry VIII; Richard de la Pole)

This chapter opens with an account of how Henry VII fs government brought peace and prosperity to England, relating how, when he died in 1509, his dynasty was well established and his treasury richer than it had ever been under any king before him. His son, Henry VIII, had an undoubted title to the throne as his mother's heir, if not his father's. The popularity of the new King, and the conscious cultivation by him of an

aura of majesty grander than had yet been manifested by his predecessors, now made any threat from the Yorkist faction at court seem

insignificant. But Henry VIII had inherited his father's sensitivity about the right of the Tudor dynasty to occupy the throne, and he pursued a similar policy throughout his reign, neutralising some of his uncomfortably close and often untrustworthy relatives, and eliminating the rest.

As late as 1538, the King told the French ambassador that he was resolved to exterminate the White Rose faction.

The de la Poles had continued to be a menace to the Tudors since the death of the Earl of Lincoln at Stoke in H87. This chapter traces the family's fortunes through the period 1487 to 1525, outlining the conspiracy in 1502 between the de la Poles and Sir James Tyrell - the alleged to have been the man instructed by Richard III to murder the Princes in the Tower - and recounting the fates of the various conspirators. Tyrell, after supposedly confessing to the murders, was executed. Lincoln's brother, William de la Pole, was sent to the Tower, where he remained until his death in 1539. Edmund de la Pole, Earl of Suffolk, the next brother, escaped into exile abroad with his younger brother Richard. In 1506 Suffolk was handed over to Henry VII by the Duke of Burgundy, as one of the conditions of the Treaty of Windsor. Another conspirator, William Courtenay, the King's own brother-in-law and husband of Katharine of York, was also punished; the Courtenay family were to identify themselves with the Yorkist cause during the reign of Henry VIII.

Suffolk spent seven years in the Tower of London, because of who he was rather than for what he had done, and gave no trouble. But when, in 1513 Henry VIII went to war with France, he made sure that any threat to England's security during his absence was removed. Thus there was a "spring cleaning at the Tower" and Suffolk lost his head, an event that went largely unnoticed at the time.

By contrast, Henry VIII's treated Margaret Pole generously, and restored her to her mother's earldom of Salisbury. Her life at this time, when she was in high favour with the King, is described, in order to illustrate that, despite her nearness in blood to the throne, she could co-exist peacefully with a Tudor monarch, There was no hint at this time of the tragedies in store for her.

After the execution of Suffolk, most members of the de la Pole family were dead, imprisoned or otherwise neutralised. Only one remained to trouble Henry VIII, and this chapter ends with an account of the career and intrigues of the exiled Richard de la Pole, whose travels took him as far as Hungary, but who later based himself at the French court, where Francis I acknowledged him as rightful King of England. Richard, who was known as "the White Rose" by English spies, continued to plague Henry VIII, remaining tantalisingly out of reach until 1525, when he met his death fighting heroically for the French at the Battle of Pavia in Italy.

The chapter concludes with a brief mention of the fortunes of the surviving members of his family.

CHAPTER EIGHT: BUCKINGHAM

(L-R: Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham; Cardinal Wolsey; Buckingham's castle of Thornbury)

Henry VIII did not have a reputation for being a bloodthirsty tyrant during the early years of his reign, and when he executed the Duke of Buckingham for treason in 1521, most people thought he was entirely justified in doing so. Edward Stafford, Duke of Buckingham, was one of the richest and most influential men at court. The King's cousin and close companion, he was not descended from the House of York, but had a claim to the throne that went back further than that, being the senior male descendant of Thomas of Woodstock, Earl of Buckingham and Duke of Gloucester, youngest son of the prolific Edward III. As such, Buckingham considered he had a better right to the throne than Henry VIII. He was the son of that Duke of Buckingham who had been executed by Richard III in 1483 for his involvement with Henry Tudor. Edward Stafford secretly despised the new dynasty, offended Cardinal Wolsey - whom he considered an upstart - and made derisory remarks about the King's lack of male heirs, a subject about which Henry VIII was extremely sensitive.

When Henry had married Katherine of Aragon in 1509, it was expected that they would soon have sons to ensure the succession. Yet of Katherine's six children, only one, the Princess Mary, survived infancy. Henry shared the aversion of his subjects to female sovereigns, and to him having a daughter was the equivalent of being childless. The problem of the succession was to torment him for twenty-eight years, until the birth of a son to his third wife, Jane Seymour, in 1537, and would be one of the causes of Henry's break with the Church of Rome and the Reformation. The Tudor succession problem underlined the insecurity of the usurping dynasty and gave rise to all kinds of speculation as to what would happen if the King died suddenly. It also drew attention to the fact that there were several descendants of the House of Plantagenet who might be willing and able to press their claims. Should Henry die without a male heir, civil war was seen as inevitable.

Buckingham was one of those who looked covetously at the throne. His indiscreet remarks about his regal ambitions were overheard by Wolsey's spies, who had had the Duke under surveillance for some time. Buckingham was arrested in 1521, tried, convicted and condemned to death. He died horribly.

CCHAPTER NINE: THE GOVERNESS AND THE PRIEST

(Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury; Cardinal Reginald Pole)

By 1530, Tudor government had been established for forty-five years, yet the threat of civil war over a disputed succession persisted. With the death of Richard de la Pole in 1525, the immediate Plantagenet threat was removed and Henry VIII could afford to be benign and generous to his surviving relatives. In 1525 he appointed Margaret Pole, whom he liked and respected, as state governess to the Princess Mary. However, his affection for Margaret would later turn sour when he learned she was supporting Mary's protests against the annulment of his marriage her mother, Queen Katherine, one of Margaret Pole's dearest friends. Henry had been a good friend to the Pole family, financing the education of the Countess's son Reginald and furthering the career of the eldest boy, Henry, Lord Montagu, at court. Margaret Pole and Katherine of Aragon had hoped for a marriage between Reginald Pole and the Princess Mary and the unification thereby of the Houses of York and Tudor. But this was not to be. Henry would allow his daughter to marry no one, lest her husband espouse her cause.

When Henry VIII married Anne Boleyn in 1533, Reginald Pole was already an exile in Italy because he could not countenance the King's divorce, and the Pole family fell from favour. The King's 'Great Matter' polarised the loyalties of his Plantagenet relatives, all of whom espoused the cause of the Queen and supported the conservative faction at court against the Church reformists. This chapter concentrates mainly on the fortunes of Margaret Pole and her children up to 1537, and relates why she was dismissed from her post of royal governess in 1533. It also charts the early life and disaffection of Reginald Pole, who took holy orders, issued a stinging diatribe against the King, and was made a cardinal by the Pope. Later he would be entrusted with bringing England back into the fold of the Roman Catholic Church.

Pole's actions adversely affected his family, helped to alienate them from the King and caused them to identify themselves with the interests of the old royal House and the political manoeuvres of the Papist faction at court.

The Pilgrimage of Grace of 1536/7, the ill-fated rebellion by the men of the north and east of England who wished to halt the King's religious reforms, received the support of Cardinal Pole and led to the King regarding Pole as his worst enemy and an arch-traitor. So vehemently did Henry now hate his former protegee that he ordered several attempts to assassinate him. The last part of this chapter chronicle Pole's treasonable activities and their effects on his family.

CHAPTER TEN: THE MEN WHO WOULD BE KING

(Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter)

The Poles were not the only members of the Yorkist faction to resent the new order in England. This chapter traces the life and career of Henry Courtenay, Marquess of Exeter, the son of Elizabeth of York's sister Katherine. Once the boyhood companion of the King, Exeter came to be one of Henry's closest confidantes. But in the 1530s he espoused the cause of Mary Tudor and identified himself with the Papist faction at court, thereby alienating the King.

Unfortunately for Exeter, both he and Lord Montagu (the eldest son of Lady Salisbury and brother of Cardinal Pole) were overheard making several indiscreet and potentially treasonous remarks, which were reported to the King's chief minister, Thomas Cromwell. Cromwell, hoping to find evidence of a White Rose conspiracy against Henry's life, arrested and interrogated Montagu's younger brother, Geoffrey Pole, who was subjected to some kind of psychological torture. In the end, he told his interrogators all they wished to know, with the result that his brother Montagu, his mother, Lady Salisbury, the Marquess of Exeter and several others were arrested and imprisoned in the Tower. Montagu, Exeter, and their so-called accomplices met their deaths on the block. Geoffrey Pole was pardoned, but died twenty years later never having forgiven himself for betraying his kinsfolk.

Margaret Pole, her grandson, Henry Pole, and Exeter's wife and children were kept in prison in the Tower without trial. This chapter relates these grim events and delves into the real reasons for the so-called Exeter conspiracy.

CHAPTER ELEVEN: NO TRAITOR

(Arthur Plantagenet, Viscount Lisle; Margaret Pole; Tower Green where Margaret died)

In 1539 Margaret Pole was attainted and sentenced tb forfeiture of life and goods. Henry VIII confiscated her goods, but spared her life, yet kept her in the Tower, where her confinement was rigorous. The King suspected her, old lady as she was, of having designs upon his throne. A banner had been found in her house depicting the royal arms without any of the armorial differences appropriate to those persons of lesser rank than the sovereign. This was enough to convince Henry that Margaret Pole was a traitor - this, and the fact that she was Reginald Pole's mother and had nurtured at her bosom two proven traitors.

Margaret Pole was not the only person of Plantagenet birth to suffer imprisonment in the Tower at this time. Arthur Plantagenet, Viscount Lisle, an illegitimate son of Edward IV, had served Henry VIII faithfully for years, latterly as deputy governor of Calais, then an English possession. Now nearing eighty, he had the misfortune to be innocently enmeshed in a Papist conspiracy to overthrow English rule in Calais. Recalled home peremptorily, Arthur found himself a prisoner in the Tower and facing the prospect of imminent execution. But this never came to pass. Henry VIII was fond of his uncle and realist enough to perceive that Arthur had been unaware of what was going on under his very nose. So Arthur escaped death at the King's hands, although he was kept in solitary confinement for nearly two years.

In the spring of 1541, Henry VIII was making plans to go on a northern progress when Sir John Neville led a rebellion in the north. Immediately the King decided to clear the Tower of important prisoners before leaving London. What-happened to the unfortunate Arthur Plantagenet is described here, but the climax to the chapter is the terrible fate of Margaret Pole, which was seen even in that brutal age as a dreadful atrocity and a gross miscarriage of justice. For Henry VIII ordered the sixty-seven-year-old Countess's immediate execution, in case she prove a focal point for traitors. Her imprisonment and her horrific end are chronicled here.

CHAPTER TWELVE: THE CAPTIVE AND THE CARDINAL

(Edward Courtenay, Earl of Devon; Cardinal Reginald Pole)

This final chapter recounts the fate of the surviving Yorkists after Henry VIII's purges of 1538/41. It charts the long captivity of Edward Gourtenay, Exeter's son, through the reigns of Henry VIII, Edward VI, Jane and Mary I, and describes his release at Mary's hands. There was talk of Courtenay marrying either the Queen and thus uniting the Houses of Tudor and Plantagenet. But Edward Gourtenay never got to be King Consort: Mary married Philip of Spain instead, and Courtenay, restored in blood and honours, went abroad where he died of an excess of debauchery - or possibly or poison - in 1556.

The chapter takes a retrospective look at the career of Cardinal Pole, who long before had been mooted as a husband for Mary. Instead he became her Archbishop of Canterbury and masterminded the counter-reformation in England. He was also to a degree responsible for the wholesale burning of heretics in Mary's reign.

This chapter also contains an investigation into the true facts behind the disappearance of young Henry Pole, Reginald's nephew, in the Tower, and recounts the fate of Lady Exeter and her children. It ends in November 1558 with the death of Cardinal Pole, within hours of the demise of the Queen he had served so loyally,

EPILOGUE: THE LAST PLANTAGENETS

(The Tower of London, where many with Plantagenet blood perished)

With the succession of Elizabeth I in 1558, the Yorkist threat to the Tudor dynasty had been consigned to history. There were now very few survivors from the old royal House. The de la Pole line had long since died out, as had the Courtenay descendants of Katherine of York. Several descendants of Margaret Pole still lived, notably her daughter Ursula, married to Buckingham's son, Lord Stafford, their son Arthur. Both Ursula and Stafford died in 1570. Then there were Margaret's grandchildren, the issue of Lord Montagu and of Geoffrey Pole. The epilogue to the book traces their fortunes, and their descendants as far as possible. It also focuses upon the involvement of Arthur, Geoffrey Pole's son, in a plot to place Mary, Queen of Scots on the English throne in 1562/3. Arthur was condemned to death for high treason, but the sentence was never carried out, and he spent the rest of his days as a prisoner in the Tower. Not only did he follow the family tradition in this respect, but also in identifying himself with reactionary politics, as his forbears had done.

The book ends with a concise analysis of why the Plantagenets failed to re-establish themselves on the throne of England.

Anyone interested in reading more about Margaret Pole might like to go to the Henry VIII: King and Court page to read the proposal for my unpublished biography of her.

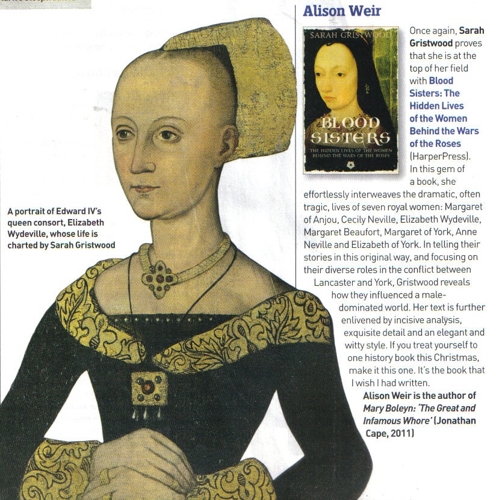

Below, from B.B.C. History Magazine's BOOKS OF THE YEAR 2012 supplement, is my review of Sarah Gristwood's wonderful book, Blood Sisters.

Unedited original review:

Once again, Sarah Gristwood proves that she is at the top of her field with this gem of a book, in which she effortlessly interweaves the dramatic, often tragic, lives of seven royal women: Margaret of Anjou, Cecily Neville, Elizabeth Wydeville, Margaret Beaufort, Margaret of York, Anne Neville and Elizabeth of York. Any one of these is a gift to a biographer, but in telling their stories in this original way, and focusing on their diverse roles in the conflict between Lancaster and York, Gristwood achieves new insights into their lives, and reveals how they influenced the course of history in a male-dominated world. Her text, informed by a judicious use of sources, is further enlivened by incisive analysis, exquisite detail and an elegant, engaging and witty style. If you treat yourself to one history book this Christmas, make it this one. It's the book I wish I had written.

BLOOD SISTERS by SARAH GRISTWOOD

Review by Alison Weir, 2013

Forget The White Queen: this is the authentic story of the women of the Wars of the Roses. Sarah Gristwood is a first-rate historian and writer, as evidenced by this insightful and extensively researched book, in which she interweaves the dramatic, often tragic, lives of seven royal ladies. All had a role to play in the bloody conflict between the houses of Lancaster and York that overshadowed the second half of the fifteenth century and led to the accession of the Tudor dynasty. It is a complicated period even for historians, but Gristwood handles her material effortlessly, displaying an impressive knowledge of the often-conflicting sources and an objective grasp of the controversies that surround her subjects.

Cecily Neville, matriarch of the House of York, whose life spans those of all the other women in the book, was the first to be born. A great-granddaughter of King Edward III, she married her cousin, Richard, Duke of York, and they had at least eleven children, including Edward IV and Richard III. Cecily outlived both kings and survived to see her granddaughter, Elizabeth of York, marry Henry VII, first sovereign of the house of Tudor. Gristwood examines recent claims that Edward IV was Cecily's son by an archer, and reaches an interesting conclusion.

Margaret of Anjou was the wife of Henry VI, last sovereign of the house of Lancaster. She was pro-active in campaigning for her husband during the wars, but was consequently unpopular and slandered by her enemies. Her story, and Cecily's, shows how women were easy targets for propaganda.

Edward IV's marriage to Elizabeth Wydeville caused scandal, not only because it was made for love instead of political advantage, but also because it advanced her family and fatally - as it proved - created a powerful court faction.

Gristwood relates how Margaret Beaufort, the mother of Henry VII, intrigued to make her son king and was thereafter hugely influential. She tells how Margaret of York, the sister of Edward IV, plotted ceaselessly to overthrow Henry by supporting pretenders to his throne.

Anne Neville, Richard III's queen, is a shadowy figure thanks to the paucity of source material. Gristwood remains determinedly neutral on the pivotal issue of the fate of the Princes in the Tower, which greatly impacted on the lives of her subjects, especially the two Elizabeths. Clearly she feels that there is insufficient evidence to condemn or exonerate Richard III.

It is fascinating to look at the Wars of the Roses from the female perspective, as Gristwood does in this book. In recounting the lives of these seven women in this original way, and focusing on their diverse roles in the conflict between Lancaster and York, she achieves new insights and reveals how they influenced the course of history in a world dominated by men. Informed by a judicious use of quotes, her work is further enlivened by perceptive analysis, vivid detail giving us glimpses of the very texture of the age, and a graceful, captivating and lively style.

MISCELLANY

Recently there has been some debate about the origins of the term 'the Cousins' Wars', which I use in this book. When I researched it in the early nineties, several respected sources stated that this was the contemporary term for what we now call the Wars of the Roses. Now this has been questioned, and I've been searching for a reference in the original sources. There doesn't seem to be any, and the evidence we have suggests that the Wars of the Roses is a far more authentic title, and closer to the period. If anyone finds any reference to the contemporary use of 'the Cousins' Wars', I'd be very grateful if they could get in touch. I'd like to add that it is also incorrect to use the term 'the War of the Roses', as there were two successive wars, the first (between York and Lancaster) from 1455 to 1471, and the second (between York and Tudor, representing Lancaster) from 1483-5.

The 15th-century carvings of Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou, mentioned on page 117 of the book, are in the Post Room, the principal floor of Archbishop Chichele`s tower (the so-called Lollards` Tower) at Lambeth Palace, built in 1434-5. My research notes have references to some other images of Margaret of Anjou: the head-and-shoulders medallion in the Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris; the medallion dated 1463 by Pietro de Milano in the Victoria and Albert Museum; an illumination of Margaret at prayer in the book of the Fraternity of Our Lady`s Assumption (now the Worshipful Company of Skinners); am illustration of Margaret`s marriage to Henry VI in the Royal MSS. in the British Library; an illustration of Henry VI and Margaret kneeling before the altar in Eton College Chapel in MS. Polychronicon, Eton College Library; the early Tudor representation of Margaret in the Coventry Tapestry in St Mary`s Hall, Coventry; a worn corbel head with flowing hair, said to be Margaret, in porch of Henley-in-Arden Church, Warwickshire; the heads of Henry VI and Margaret on 500-year-old bell at Great Ness Church, Shropshire; bell said to have come from Valle Crucis Abbey, North Wales; a carving of Margaret (protecting her son) and the robber on an old chair in Wrockwardine Church. Shropshire; an illumination of Henry VI and Margaret with John Talbot, Earl of Shrewsbury in the King`s MSS., British Library); a stained-glass image of Margaret kneeling in prayer in the Church of the Cordeliers at Angers, an 18th-century copy of a 15th-century window.

Elizabeth Lucy (nee Wayte) was the mistress of Edward IV and had by him Arthur Plantagenet; some modern sources also claim she was the mother of the King`s bastard daughter Elizabeth, although Sir Thomas More wrote that Elizabeth Lucy had `a child` by the King, so this is open to question. More states that Elizabeth Lucy bore the King a child before his marriage in 1464, so some have assumed this was Elizabeth, although it was more likely to have been Arthur Plantagenet. Elizabeth married Sir Thomas Lumley (1462-1507) before 1478 (CIPM) and had issue. Contemporary evidence for this marriage appears in later Lumley monument in the church of Chester-le-Street, a Neville pedigree of c1505, and a 1530 visitation of the northern counties. The antiquary John Leland, writing earlier in Henry VIII`s reign, says that Elizabeth married Thomas, Lord Lumley, and that this was the reason for him being raised to the peerage in 1461. Since Arthur Plantagenet was born around 1461-4, and his (half?) sister probably around that time, this seems an unlikely claim. Moreover, Lord Lumley`s wife`s name is known. (Source is Complete Peerage) Elizabeth`s eldest son was Richard, Baron Lumley (c1478-1510); her other children were John, George, Roger, Sybil, Elizabeth and Anne. Her date of death is not recorded, but she must have lived at least until the early 1490s.

Please note that the Battle of Formigny was fought on 15th April 1450, not 15th August, as incorrectly stated in the book. Apologies!

In 2004, after watching Tony Robinson's television programme questioning Edward IV s illegitimacy a reader wrote "I was prompted to re-read your very enjoyable book, Lancaster v York (The Wars of the Roses) and as I had thought in your Chapter 'Murder at Sea' your view was that Cecily's piety was legendary and that she had protested vehemently against being slandered when it was suggested that her sons were bastards. However, curiously, this seems to be in stark contrast to Tony Robinson's view that she made no attempt to contradict these claims. I am curious to know how two researchers can come up with such opposing evidence."

I replied: "I too watched Tony Robinson's programme, and stand by what I wrote in my books on the period. The allegations against the Duchess Cecily first surfaced in 1469, when they were used as propaganda by the Duke of Clarence and Warwick the Kingmaker to discredit Edward IV, against whom these lords had risen in rebellion. They were again used by Richard of Gloucester in 1483 to justify his claim to the throne. However, these slanders against the pious Duchess of York were met with silent derision by the Londoners, so Richard came up with the story about Edward IV's precontract to Eleanor Butler. This was scant comfort to the Duchess, who, according to Polydore Vergil, complained loudly to many noble men that her son had done her a great injury. The tale that Cecily, outraged by Edward IV's marriage to a commoner, Elizabeth Wydeville, in 1464, offered to declare him a bastard, comes from Dominic Mancini, and dates from that same summer of 1483. It probably reflects rumours current at the time, and is not contemporary evidence. Allegations of bastardy were common propaganda tools in the fifteenth century."